Полная версия

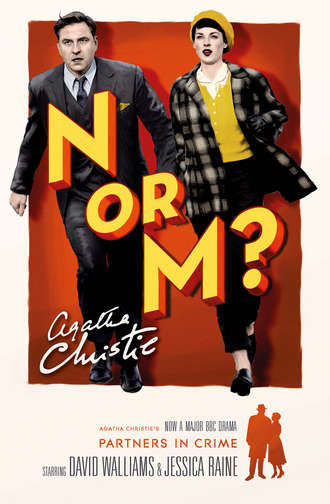

N or M?

Mrs Perenna groaned and said:

‘This terrible war—’

Tommy agreed and said that in his opinion that fellow Hitler ought to be hanged. A madman, that’s what he was, a madman.

Mrs Perenna agreed and said that what with rations and the difficulty the butchers had in getting the meat they wanted—and sometimes too much and sweet-breads and liver practically disappeared, it all made housekeeping very difficult, but as Mr Meadowes was a relation of Miss Meadowes, she would make it half a guinea less.

Tommy then beat a retreat with the promise to think it over and Mrs Perenna pursued him to the gate, talking more volubly than ever and displaying an archness that Tommy found most alarming. She was, he admitted, quite a handsome woman in her way. He found himself wondering what her nationality was. Surely not quite English? The name was Spanish or Portuguese, but that would be her husband’s nationality, not hers. She might, he thought, be Irish, though she had no brogue. But it would account for the vitality and the exuberance.

It was finally settled that Mr Meadowes should move in the following day.

Tommy timed his arrival for six o’clock. Mrs Perenna came out into the hall to greet him, threw a series of instructions about his luggage to an almost imbecile-looking maid, who goggled at Tommy with her mouth open, and then led him into what she called the lounge.

‘I always introduce my guests,’ said Mrs Perenna, beaming determinedly at the suspicious glares of five people. ‘This is our new arrival, Mr Meadowes—Mrs O’Rourke.’ A terrifying mountain of a woman with beady eyes and a moustache gave him a beaming smile.

‘Major Bletchley.’ Major Bletchley eyed Tommy appraisingly and made a stiff inclination of the head.

‘Mr von Deinim.’ A young man, very stiff, fair-haired and blue-eyed, got up and bowed.

‘Miss Minton.’ An elderly woman with a lot of beads, knitting with khaki wool, smiled and tittered.

‘And Mrs Blenkensop.’ More knitting—an untidy dark head which lifted from an absorbed contemplation of a Balaclava helmet.

Tommy held his breath, the room spun round.

Mrs Blenkensop! Tuppence! By all that was impossible and unbelievable—Tuppence, calmly knitting in the lounge of Sans Souci.

Her eyes met his—polite, uninterested stranger’s eyes.

His admiration rose.

Tuppence!

CHAPTER 2

How Tommy got through that evening he never quite knew. He dared not let his eyes stray too often in the direction of Mrs Blenkensop. At dinner three more habitués of Sans Souci appeared—a middle-aged couple, Mr and Mrs Cayley, and a young mother, Mrs Sprot, who had come down with her baby girl from London and was clearly much bored by her enforced stay at Leahampton. She was placed next to Tommy and at intervals fixed him with a pair of pale gooseberry eyes and in a slightly adenoidal voice asked: ‘Don’t you think it’s really quite safe now? Everyone’s going back, aren’t they?’

Before Tommy could reply to these artless queries, his neighbour on the other side, the beaded lady, struck in:

‘What I say is one mustn’t risk anything with children. Your sweet little Betty. You’d never forgive yourself and you know that Hitler has said the Blitzkrieg on England is coming quite soon now—and quite a new kind of gas, I believe.’

Major Bletchley cut in sharply:

‘Lot of nonsense talked about gas. The fellows won’t waste time fiddling round with gas. High explosive and incendiary bombs. That’s what was done in Spain.’

The whole table plunged into the argument with gusto. Tuppence’s voice, high-pitched and slightly fatuous, piped out: ‘My son Douglas says—’

‘Douglas, indeed,’ thought Tommy. ‘Why Douglas, I should like to know.’

After dinner, a pretentious meal of several meagre courses, all of which were equally tasteless, everyone drifted into the lounge. Knitting was resumed and Tommy was compelled to hear a long and extremely boring account of Major Bletchley’s experiences on the North-West Frontier.

The fair young man with the bright blue eyes went out, executing a little bow on the threshold of the room.

Major Bletchley broke off his narrative and administered a kind of dig in the ribs to Tommy.

‘That fellow who’s just gone out. He’s a refugee. Got out of Germany about a month before the war.’

‘He’s a German?’

‘Yes. Not a Jew either. His father got into trouble for criticising the Nazi régime. Two of his brothers are in concentration camps over there. This fellow got out just in time.’

At this moment Tommy was taken possession of by Mr Cayley, who told him at interminable length all about his health. So absorbing was the subject to the narrator that it was close upon bedtime before Tommy could escape.

On the following morning Tommy rose early and strolled down to the front. He walked briskly to the pier returning along the esplanade when he spied a familiar figure coming in the other direction. Tommy raised his hat.

‘Good morning,’ he said pleasantly. ‘Er—Mrs Blenkensop, isn’t it?’

There was no one within earshot. Tuppence replied:

‘Dr Livingstone to you.’

‘How on earth did you get here, Tuppence?’ murmured Tommy. ‘It’s a miracle—an absolute miracle.’

‘It’s not a miracle at all—just brains.’

‘Your brains, I suppose?’

‘You suppose rightly. You and your uppish Mr Grant. I hope this will teach him a lesson.’

‘It certainly ought to,’ said Tommy. ‘Come on, Tuppence, tell me how you managed it. I’m simply devoured with curiosity.’

‘It was quite simple. The moment Grant talked of our Mr Carter I guessed what was up. I knew it wouldn’t be just some miserable office job. But his manner showed me that I wasn’t going to be allowed in on this. So I resolved to go one better. I went to fetch some sherry and, when I did, I nipped down to the Browns’ flat and rang up Maureen. Told her to ring me up and what to say. She played up loyally—nice high squeaky voice—you could hear what she was saying all over the room. I did my stuff, registered annoyance, compulsion, distressed friend, and rushed off with every sign of vexation. Banged the hall door, carefully remaining inside it, and slipped into the bedroom and eased open the communicating door that’s hidden by the tallboy.’

‘And you heard everything?’

‘Everything,’ said Tuppence complacently.

Tommy said reproachfully:

‘And you never let on?’

‘Certainly not. I wished to teach you a lesson. You and your Mr Grant.’

‘He’s not exactly my Mr Grant and I should say you have taught him a lesson.’

‘Mr Carter wouldn’t have treated me so shabbily,’ said Tuppence. ‘I don’t think the Intelligence is anything like what it was in our day.’

Tommy said gravely: ‘It will attain its former brilliance now we’re back in it. But why Blenkensop?’

‘Why not?’

‘It seems such an odd name to choose.’

‘It was the first one I thought of and it’s handy for underclothes.’

‘What do you mean, Tuppence?’

‘B, you idiot. B for Beresford. B for Blenkensop. Embroidered on my camiknickers. Patricia Blenkensop. Prudence Beresford. Why did you choose Meadowes? It’s a silly name.’

‘To begin with,’ said Tommy, ‘I don’t have large B’s embroidered on my pants. And to continue, I didn’t choose it. I was told to call myself Meadowes. Mr Meadowes is a gentleman with a respectable past—all of which I’ve learnt by heart.’

‘Very nice,’ said Tuppence. ‘Are you married or single?’

‘I’m a widower,’ said Tommy with dignity. ‘My wife died ten years ago at Singapore.’

‘Why at Singapore?’

‘We’ve all got to die somewhere. What’s wrong with Singapore?’

‘Oh, nothing. It’s probably a most suitable place to die. I’m a widow.’

‘Where did your husband die?’

‘Does it matter? Probably in a nursing home. I rather fancy he died of cirrhosis of the liver.’

‘I see. A painful subject. And what about your son Douglas?’

‘Douglas is in the Navy.’

‘So I heard last night.’

‘And I’ve got two other sons. Raymond is in the Air Force and Cyril, my baby, is in the Territorials.’

‘And suppose someone takes the trouble to check up on these imaginary Blenkensops?’

‘They’re not Blenkensops. Blenkensop was my second husband. My first husband’s name was Hill. There are three pages of Hills in the telephone book. You couldn’t check up on all the Hills if you tried.’

Tommy sighed.

‘It’s the old trouble with you, Tuppence. You will overdo things. Two husbands and three sons. It’s too much. You’ll contradict yourself over the details.’

‘No, I shan’t. And I rather fancy the sons may come in useful. I’m not under orders, remember. I’m a freelance. I’m in this to enjoy myself and I’m going to enjoy myself.’

‘So it seems,’ said Tommy. He added gloomily: ‘If you ask me the whole thing’s a farce.’

‘Why do you say that?’

‘Well, you’ve been at Sans Souci longer than I have. Can you honestly say you think any of these people who were there last night could be a dangerous enemy agent?’

Tuppence said thoughtfully:

‘It does seem a little incredible. There’s the young man, of course.’

‘Carl von Deinim. The police check up on refugees, don’t they?’

‘I suppose so. Still, it might be managed. He’s an attractive young man, you know.’

‘Meaning, the girls will tell him things? But what girls? No Generals’ or Admirals’ daughters floating around here. Perhaps he walks out with a Company Commander in the ATS.’

‘Be quiet, Tommy. We ought to be taking this seriously.’

‘I am taking it seriously. It’s just that I feel we’re on a wild-goose chase.’

Tuppence said seriously:

‘It’s too early to say that. After all, nothing’s going to be obvious about this business. What about Mrs Perenna?’

‘Yes,’ said Tommy thoughtfully. ‘There’s Mrs Perenna, I admit—she does want explaining.’

Tuppence said in a business-like tone:

‘What about us? I mean, how are we going to cooperate?’

Tommy said thoughtfully:

‘We mustn’t be seen about too much together.’

‘No, it would be fatal to suggest we know each other better than we appear to do. What we want to decide is the attitude. I think—yes, I think—pursuit is the best angle.’

‘Pursuit?’

‘Exactly. I pursue you. You do your best to escape, but being a mere chivalrous male don’t always succeed. I’ve had two husbands and I’m on the look-out for a third. You act the part of the hunted widower. Every now and then I pin you down somewhere, pen you in a café, catch you walking on the front. Everyone sniggers and thinks it very funny.’

‘Sounds feasible,’ agreed Tommy.

Tuppence said: ‘There’s a kind of age-long humour about the chased male. That ought to stand us in good stead. If we are seen together, all anyone will do is to snigger and say, “Look at poor old Meadowes.”’

Tommy gripped her arm suddenly.

‘Look,’ he said. ‘Look ahead of you.’

By the corner of one of the shelters a young man stood talking to a girl. They were both very earnest, very wrapped up in what they were saying.

Tuppence said softly:

‘Carl von Deinim. Who’s the girl, I wonder?’

‘She’s remarkably good-looking, whoever she is.’

Tuppence nodded. Her eyes dwelt thoughtfully on the dark passionate face, and on the tight-fitting pullover that revealed the lines of the girl’s figure. She was talking earnestly, with emphasis. Carl von Deinim was listening to her.

Tuppence murmured:

‘I think this is where you leave me.’

‘Right,’ agreed Tommy.

He turned and strolled in the opposite direction.

At the end of the promenade he encountered Major Bletchley. The latter peered at him suspiciously and then grunted out, ‘Good morning.’

‘Good morning.’

‘See you’re like me, an early riser,’ remarked Bletchley.

Tommy said:

‘One gets in the habit of it out East. Of course, that’s many years ago now, but I still wake early.’

‘Quite right, too,’ said Major Bletchley with approval. ‘God, these young fellows nowadays make me sick. Hot baths—coming down to breakfast at ten o’clock or later. No wonder the Germans have been putting it over on us. No stamina. Soft lot of young pups. Army’s not what it was, anyway. Coddle ’em, that’s what they do nowadays. Tuck ’em up at night with hot-water bottles. Faugh! Makes me sick!’

Tommy shook his head in melancholy fashion and Major Bletchley, thus encouraged, went on:

‘Discipline, that’s what we need. Discipline. How are we going to win the war without discipline? Do you know, sir, some of these fellows come on parade in slacks—so I’ve been told. Can’t expect to win a war that way. Slacks! My God!’

Mr Meadowes hazarded the opinion that things were very different from what they had been.

‘It’s all this democracy,’ said Major Bletchley gloomily. ‘You can overdo anything. In my opinion they’re overdoing the democracy business. Mixing up the officers and the men, feeding together in restaurants—Faugh!—the men don’t like it, Meadowes. The troops know. The troops always know.’

‘Of course,’ said Mr Meadowes, ‘I have no real knowledge of Army matters myself—’

The Major interrupted him, shooting a quick sideways glance. ‘In the show in the last war?’

‘Oh yes.’

‘Thought so. Saw you’d been drilled. Shoulders. What regiment?’

‘Fifth Corfeshires.’ Tommy remembered to produce Meadowes’ military record.

‘Ah yes, Salonica!’

‘Yes.’

‘I was in Mespot.’

Bletchley plunged into reminiscences. Tommy listened politely. Bletchley ended up wrathfully.

‘And will they make use of me now? No, they will not. Too old. Too old be damned. I could teach one or two of these young cubs something about war.’

‘Even if it’s only what not to do?’ suggested Tommy with a smile.

‘Eh, what’s that?’

A sense of humour was clearly not Major Bletchley’s strong suit. He peered suspiciously at his companion. Tommy hastened to change the conversation.

‘Know anything about that Mrs—Blenkensop, I think her name is?’

‘That’s right, Blenkensop. Not a bad-looking woman—bit long in the tooth—talks too much. Nice woman, but foolish. No, I don’t know her. She’s only been at Sans Souci a couple of days.’ He added: ‘Why do you ask?’

Tommy explained.

‘Happened to meet her just now. Wondered if she was always out as early as this?’

‘Don’t know, I’m sure. Women aren’t usually given to walking before breakfast—thank God,’ he added.

‘Amen,’ said Tommy. He went on: ‘I’m not much good at making polite conversation before breakfast. Hope I wasn’t rude to the woman, but I wanted my exercise.’

Major Bletchley displayed instant sympathy.

‘I’m with you, Meadowes. I’m with you. Women are all very well in their place, but not before breakfast.’ He chuckled a little. ‘Better be careful, old man. She’s a widow, you know.’

‘Is she?’

The Major dug him cheerfully in the ribs.

‘We know what widows are. She’s buried two husbands and if you ask me she’s on the look-out for number three. Keep a very wary eye open, Meadowes. A wary eye. That’s my advice.’

And in high good humour Major Bletchley wheeled about at the end of the parade and set the pace for a smart walk back to breakfast at Sans Souci.

In the meantime, Tuppence had gently continued her walk along the esplanade, passing quite close to the shelter and the young couple talking there. As she passed she caught a few words. It was the girl speaking.

‘But you must be careful, Carl. The very least suspicion—’

Tuppence was out of earshot. Suggestive words? Yes, but capable of any number of harmless interpretations. Unobtrusively she turned and again passed the two. Again words floated to her.

‘Smug, detestable English…’

The eyebrows of Mrs Blenkensop rose ever so slightly. Carl von Deinim was a refugee from Nazi persecution, given asylum and shelter by England. Neither wise nor grateful to listen assentingly to such words.

Again Tuppence turned. But this time, before she reached the shelter, the couple had parted abruptly, the girl to cross the road leaving the sea front, Carl von Deinim to come along to Tuppence’s direction.

He would not, perhaps, have recognised her but for her own pause and hesitation. Then quickly he brought his heels together and bowed.

Tuppence twittered at him:

‘Good morning, Mr von Deinim, isn’t it? Such a lovely morning.’

‘Ah, yes. The weather is fine.’

Tuppence ran on:

‘It quite tempted me. I don’t often come out before breakfast. But this morning, what with not sleeping very well—one often doesn’t sleep well in a strange place, I find. It takes a day or two to accustom oneself, I always say.’

‘Oh yes, no doubt that is so.’

‘And really this little walk has quite given me an appetite for breakfast.’

‘You go back to Sans Souci now? If you permit I will walk with you.’ He walked gravely by her side.

Tuppence said:

‘You also are out to get an appetite?’

Gravely, he shook his head.

‘Oh no. My breakfast I have already had it. I am on my way to work.’

‘Work?’

‘I am a research chemist.’

‘So that’s what you are,’ thought Tuppence, stealing a quick glance at him.

Carl von Deinim went on, his voice stiff:

‘I came to this country to escape Nazi persecution. I had very little money—no friends. I do now what useful work I can.’

He stared straight ahead of him. Tuppence was conscious of some undercurrent of strong feeling moving him powerfully.

She murmured vaguely:

‘Oh yes, I see. Very creditable, I am sure.’

Carl von Deinim said:

‘My two brothers are in concentration camps. My father died in one. My mother died of sorrow and fear.’

Tuppence thought:

‘The way he says that—as though he had learned it by heart.’

Again she stole a quick glance at him. He was still staring ahead of him, his face impassive.

They walked in silence for some moments. Two men passed them. One of them shot a quick glance at Carl. She heard him mutter to his companion:

‘Bet you that fellow is a German.’

Tuppence saw the colour rise in Carl von Deinim’s cheeks.

Suddenly he lost command of himself. That tide of hidden emotion came to the surface. He stammered:

‘You heard—you heard—that is what they say—I—’

‘My dear boy,’ Tuppence reverted suddenly to her real self. Her voice was crisp and compelling. ‘Don’t be an idiot. You can’t have it both ways.’

He turned his head and stared at her.

‘What do you mean?’

‘You’re a refugee. You have to take the rough with the smooth. You’re alive, that’s the main thing. Alive and free. For the other—realise that it’s inevitable. This country’s at war. You’re a German.’ She smiled suddenly. ‘You can’t expect the mere man in the street—literally the man in the street—to distinguish between bad Germans and good Germans, if I may put it so crudely.’

He still stared at her. His eyes, so very blue, were poignant with suppressed feeling. Then suddenly he too smiled. He said:

‘They said of Red Indians, did they not, that a good Indian was a dead Indian.’ He laughed. ‘To be a good German I must be on time at my work. Please. Good morning.’

Again that stiff bow. Tuppence stared after his retreating figure. She said to herself:

‘Mrs Blenkensop, you had a lapse then. Strict attention to business in future. Now for breakfast at Sans Souci.’

The hall door of Sans Souci was open. Inside, Mrs Perenna was conducting a vigorous conversation with someone.

‘And you’ll tell him what I think of that last lot of margarine. Get the cooked ham at Quillers—it was twopence cheaper last time there, and be careful about the cabbages—’ She broke off as Tuppence entered.

‘Oh, good morning, Mrs Blenkensop, you are an early bird. You haven’t had breakfast yet. It’s all ready in the dining-room.’ She added, indicating her companion: ‘My daughter Sheila. You haven’t met her. She’s been away and only came home last night.’

Tuppence looked with interest at the vivid, handsome face. No longer full of tragic energy, bored now and resentful. ‘My daughter Sheila.’ Sheila Perenna.

Tuppence murmured a few pleasant words and went into the dining-room. There were three people breakfasting—Mrs Sprot and her baby girl, and big Mrs O’Rourke. Tuppence said ‘Good morning’ and Mrs O’Rourke replied with a hearty ‘The top of the morning to you’ that quite drowned Mrs Sprot’s more anaemic salutation.

The old woman stared at Tuppence with a kind of devouring interest.

‘’Tis a fine thing to be out walking before breakfast,’ she observed. ‘A grand appetite it gives you.’

Mrs Sprot said to her offspring:

‘Nice bread and milk, darling,’ and endeavoured to insinuate a spoonful into Miss Betty Sprot’s mouth.

The latter cleverly circumvented this endeavour by an adroit movement of her head, and continued to stare at Tuppence with large round eyes.

She pointed a milky finger at the newcomer, gave her a dazzling smile and observed in gurgling tones: ‘Ga—ga bouch.’

‘She likes you,’ cried Mrs Sprot, beaming on Tuppence as on one marked out for favour. ‘Sometimes she’s so shy with strangers.’

‘Bouch,’ said Betty Sprot. ‘Ah pooth ah bag,’ she added with emphasis.

‘And what would she be meaning by that?’ demanded Mrs O’Rourke, with interest.

‘She doesn’t speak awfully clearly yet,’ confessed Mrs Sprot. ‘She’s only just over two, you know. I’m afraid most of what she says is just bosh. She can say Mama, though, can’t you, darling?’

Betty looked thoughtfully at her mother and remarked with an air of finality:

‘Cuggle bick.’

‘’Tis a language of their own they have, the little angels,’ boomed out Mrs O’Rourke. ‘Betty, darling, say Mama now.’

Betty looked hard at Mrs O’Rourke, frowned and observed with terrific emphasis: ‘Nazer—’

‘There now, if she isn’t doing her best! And a lovely sweet girl she is.’

Mrs O’Rourke rose, beamed in a ferocious manner at Betty, and waddled heavily out of the room.

‘Ga, ga, ga,’ said Betty with enormous satisfaction, and beat with a spoon on the table.

Tuppence said with a twinkle:

‘What does Nazer really mean?’

Mrs Sprot said with a flush: ‘I’m afraid, you know, it’s what Betty says when she doesn’t like anyone or anything.’

‘I rather thought so,’ said Tuppence.

Both women laughed.

‘After all,’ said Mrs Sprot, ‘Mrs O’Rourke means to be kind but she is rather alarming—with that deep voice and the beard and—and everything.’

With her head on one side Betty made a cooing noise at Tuppence.

‘She has taken to you, Mrs Blenkensop,’ said Mrs Sprot.

There was a slight jealous chill, Tuppence fancied, in her voice. Tuppence hastened to adjust matters.

‘They always like a new face, don’t they?’ she said easily.

The door opened and Major Bletchley and Tommy appeared. Tuppence became arch.

‘Ah, Mr Meadowes,’ she called out. ‘I’ve beaten you, you see. First past the post. But I’ve left you just a little breakfast!’

She indicated with the faintest of gestures the seat beside her.

Tommy, muttering vaguely: ‘Oh—er—rather—thanks,’ sat down at the other end of the table.

Betty Sprot said ‘Putch!’ with a fine splutter of milk at Major Bletchley, whose face instantly assumed a sheepish but delighted expression.

‘And how’s little Miss Bo Peep this morning?’ he asked fatuously. ‘Bo Peep!’ He enacted the play with a newspaper.

Betty crowed with delight.

Serious misgivings shook Tuppence. She thought:

‘There must be some mistake. There can’t be anything going on here. There simply can’t!’