Полная версия

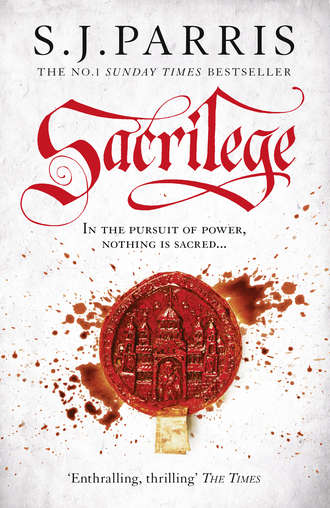

Sacrilege

‘So I understand. The Queen’s father tried to wipe out the Saint’s cult completely,’ I mused, remembering suddenly a Book of Hours I had seen in Oxford, the prayer to Saint Thomas and the accompanying illumination scraped from the parchment with a stone.

‘Folly,’ Harry pronounced, shaking his head. ‘They say that before the Dissolution there were more chapels, chantries and altars in this land dedicated to Thomas Becket than any other saint in history. You can’t erase that from people’s minds, especially not in his home town, not even by smashing the shrine. You just drive it into the shadows.’

‘Not even by destroying the body?’

He regarded me shrewdly and smiled.

‘You’ve heard the legend of Becket’s bones, then?’

‘Is it true?’

‘Quite probably.’ He emptied his cup, bent awkwardly to set it on the floor, and leaned forward, one hand on his stick. ‘Yes, I’d say it’s very likely the body they pulverised and scattered to the wind was not old Thomas. Those priory monks were no fools, and they knew the destruction was coming. But in a sense the literal truth of it doesn’t matter, you see? If enough people in Canterbury believed that Saint Thomas was still among them, it might put fire in their bellies.’

‘And do they believe it?’

He made a non-committal gesture with his head.

‘Everyone knows the legend. I dare say many of them believe it in an abstract sense. What they really need, though, is a sign. That would rouse them.’

‘A miracle, you mean?’

‘The cult of Thomas began with a miracle – here, in this cathedral, less than a week after he was murdered – and it could be revived by one too. Imagine the effect among so many disaffected souls. Like throwing a tinder-box into a pile of dry kindling. And Kent is a dangerous place to risk an uprising, as Walsingham knows all too well. Last time Kentish men rebelled they marched on London, captured the Tower and beheaded the Archbishop of Canterbury and the royal Treasurer.’

‘Really?’ I stared at him, wide-eyed. ‘I had not heard – when was this?’

Harry laughed.

‘Two hundred years ago. But Kentish men are still made of the same stuff. And the coast here is so convenient for any forces coming out of France – it’s not a place they want to risk a popular rebellion against the Crown. The Queen needs to keep Canterbury loyal.’

He fell silent and stared into the fireplace while my thoughts scrambled to catch up.

‘Do you believe in miracles?’ I asked, after a few moments.

He looked up from his reflections, his eyes bright.

‘Do I believe that Our Lord can perform wonders to show His might to men, if He chooses? Yes, of course. But He chooses very rarely, in my view. If you ask, do I believe that a four-hundred-year-old shard of rotting skull can heal the sick, then I would have to say no.’ He shifted position again, rubbing at his leg. ‘When I was six years old, in 1528, there was a terrible outbreak of the sweating sickness in England. My parents and my five brothers and sisters all died, I did not even take ill. Was that a miracle?’

He fixed me with a questioning look; I made a non-committal gesture.

‘My relatives certainly thought so – they gave me up to the Church straight away, and here I have dutifully remained, to the age of sixty-two years, because I was told so often as a child how God had spared me to serve Him. But who really knows?’

I caught the weight of sadness in his voice and wondered how often in his life as a young churchman he had stopped to wonder at the different paths he might have taken, only to be trapped by the obligation to this great miracle of his survival, God’s terrible mercy. That could have been me, I thought, with a lurch of relief, if I had not taken the opportunity to flee the religious life: white-haired and slowly suffocating in the monastery of San Domenico Maggiore, rueing the life I might have lived if I had only dared to try. I wanted to reach out and touch his crooked hand, so brittle with its swollen joints, to show that I understood, but I suspected this might alarm him. The English do not like to be touched, I have learned; they seem to regard it as a prelude to assault.

‘One need not be a doctor of physic to observe that some are better able to resist sickness than others,’ I said softly.

‘True. But one might be considered impious for failing to acknowledge the hand of God in such an occurrence.’

‘In Paris, I once saw a man at a fair make a wooden dove fly over the heads of the crowd, and that was accounted a miracle by all who witnessed it. To those of us who knew better, it was an ingenious employment of optical illusion and mechanical expertise.’

Harry raised one gnarled finger, as if to make a point.

‘But there you have it, Bruno. If it looks like a miracle, most are content to believe it is so.’

I was about to answer, but the closeness of the room and the weariness of days in the saddle conspired to make me suddenly dizzy and I almost fell, silver lights swimming before my eyes, clutching at the seat of the chair for fear I should faint. Harry peered at me, concerned.

‘Are you unwell?’

‘Forgive me.’ My voice sounded very far away. ‘Could we open a window?’

He frowned.

‘Too hot? I suppose it is hot in here. Samuel never complains and I don’t notice – it’s a curious thing about age, one is always cold. Come – we will take a walk around the close and you can see where this monstrous deed occurred.’ He straightened the stick, took a deep breath, clenched his teeth and with an almighty effort began to rouse himself to his feet. I extended a hand to him, though I still felt unsteady myself, but he brushed it away impatiently.

‘Not on my deathbed yet, son. While I can stand on my own two feet, leave me to it. I call it independence. Samuel calls it stubbornness. What time is it, Samuel?’

The servant, who had remained motionless gazing out of the window and doubtless taking in every word, now turned back to the room.

‘About half past three, I think, sir.’

‘Then we have time. I’ll want a shave before Evensong, if you could have the necessaries ready when I return.’

‘You don’t wish me to accompany you, sir?’ Samuel turned dubious eyes on me, as if the prospect of allowing his master out alone with me would be a dereliction of duty.

‘I’m sure you have things to attend to here,’ Harry said. ‘We shall probably manage a turn around the close. I dare say Doctor Bruno will pick me up if I fall over.’

‘If you’ll let me,’ I said, and when I saw the twinkle in his eye, I knew that, despite his gruff manner, he was warming to me. Samuel looked at me with a face like stormclouds.

‘My doublet, Samuel,’ Harry said, waving a hand. ‘Here, hold this, will you?’ He handed me the stick and planted his legs wide to balance himself while he tucked his shirt into his breeches. ‘Wouldn’t want to run into the Dean, looking like a vagrant,’ he muttered, with a brief smile. ‘You never know who’s about in this place. That reminds me –’ he looked up. ‘Your story, while you’re here. The reason for your visit – what do we tell people? They’re an overly curious lot, especially the Dean and Chapter.’

‘I’m a Doctor of Divinity from the University of Padua, exiled to escape religious persecution and lately studying in Oxford, where I heard much praise for the cathedral of Canterbury and wanted to take this opportunity to see it for myself.’

He considered my rehearsed biography and grunted.

‘They will accept that readily enough, I should think. And how do you and I know each other?’

‘A letter of introduction from our mutual friend, Sir Philip Sidney.’

Harry smiled at this.

‘Ah, little Philip. He was about four years old when I last saw him. Turned out well, I hear. His mother was a great beauty in her day, you know.’ His gaze drifted to the window, as though he was seeing faces from years long past. Samuel came in with a plain black doublet of light wool and helped his master into it. ‘Well, then.’ Harry gestured to the door. ‘What name do you travel under here? I had better get used to it in case I am obliged to introduce you to anyone.’

‘Filippo Savolino.’

‘Savolino. Huh.’ He repeated it twice more, as if to accustomise himself to the feel of it.

‘It is unlikely that anyone in Canterbury would know my reputation, but –’

‘We do read books here, you know. We’re not entirely cut off from learned society.’

‘No, I didn’t mean to imply –’

‘There’s quite a trade in books from the Continent, too, being so near the ports. Legal and otherwise. Including plenty from your country.’ He regarded me thoughtfully. ‘Padua, eh? I have never travelled beyond England, though as a young man I dreamed of doing so. I would have liked to see Italy for myself. A country of wild beauty, I am told.’

‘I think no man can say he has seen beauty until he has watched the sun set over the Bay of Naples, with the shadow of Mount Vesuvius in the background.’

‘A volcano. I can hardly imagine a volcano,’ he said, with simple longing.

‘Perhaps you may see it one day.’

He slapped his bad thigh and barked out another laugh. ‘With this leg? No – while you are here, you must describe it to me and I shall be able to picture it. I do not think these eyes will ever look on the Bay of Naples.’

‘Nor will mine again,’ I said, and the weight of this struck me as I spoke the words, so that I heard my voice catch at the end.

We looked at one another, the moment ripe with regret. Harry shook his head briskly, as if to rid himself of sentiment.

‘Come then, Savolino, we have work to do.’

Air, real air, with the faintest hint of a breeze carrying the indignant cries of seagulls; I was so grateful that I stood still on the garden path, head spinning as I gulped down great lungfuls like a man who has narrowly escaped drowning. Harry shuffled ahead of me into the cathedral close and motioned to his right; when I had recovered and my blood felt as if it were pumping once more, I followed him. Samuel stood in the doorway watching us with an inscrutable expression. I could not help noticing that Harry’s limp became less pronounced and his pace speeded up a little once we had rounded the corner and were out of his servant’s sight.

‘Have you ever been married, Bruno?’ he asked.

‘No,’ I said, surprised by the question. Shielding my eyes, I looked up to our left; sideways on, the cathedral had the appearance of a vast warship, ribbed with buttresses, its high windows so many gunports.

‘Nor I,’ he said. ‘When I entered the clergy, churchmen didn’t marry, and once it became acceptable, I had missed the boat. Instead I have Samuel – all the fussing and nagging of a wife, with none of the benefits.’ He gave a deep, rasping laugh.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.