Полная версия

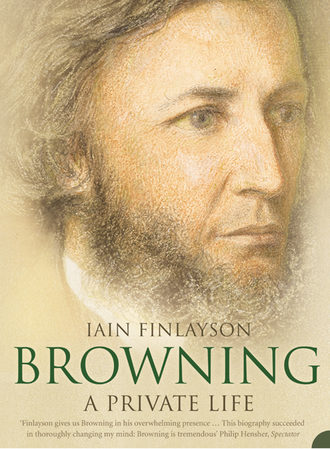

Browning

BROWNING

A Private Life

IAIN FINLAYSON

DEDICATION

to Judith Macrae,

Good Friend and Good Samaritan

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Prologue

Part 1: Robert and the Brownings 1812–1846

Part 2: Robert and Elizabeth 1846–1861

Part 3: Robert and Pen 1861–1889

Epilogue

Bibliographical Note

Abbreviations and Short Citations of Principal Sources

Index

Acknowledgements

Notes

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

HENRY JAMES, a man of sound and profound literary and personal judgements, provided the most epigrammatic epitaph for Robert Browning. On the occasion of the poet’s burial in Westminster Abbey, on 31 December 1889, he remarked: ‘A good many oddities and a good many great writers have been entombed in the Abbey, but none of the odd ones have been so great and none of the great ones so odd.’

The immortal voice having been condemned to final silence by disinterested Nature, and the mortal dust committed to elaborate interment by a respectful nation, James reflected that only Browning himself could have done literary justice to the ceremony:

‘The consignment of his ashes to the great temple of fame of the English race was exactly one of those occasions in which his own analytic spirit would have rejoiced, and his irrepressible faculty for looking at human events in all sorts of slanting coloured lights have found a signal opportunity … in a word, the author would have been sure to take the special, circumstantial view (the inveterate mark of all his speculation) even of so foregone a conclusion as that England should pay her greatest honour to one of her greatest poets.’

Browning’s greatness and his oddity, his great value, in James’ view, was that ‘in all the deep spiritual and human essentials, he is unmistakably in the great tradition—is, with all his Italianisms and cosmopolitanisms, all his victimisation by societies organised to talk about him, a magnificent example of the best and least dilettantish English spirit’. That English spirit does not, generally, delight in literary or psychological subtleties; nevertheless, stoutly and steadfastly, ‘Browning made them his perpetual pasture, and yet remained typically of his race … His voice sounds loudest, and also clearest, for the things that, as a race, we like best—the fascination of faith, the acceptance of life, the respect for its mysteries, the endurance of its charges, the vitality of the will, the validity of character, the beauty of action, the seriousness, above all, of the great human passion.’

James particularly distinguished Browning as ‘a tremendous and incomparable modern’ who ‘introduces to his predecessors a kind of contemporary individualism’ long forgotten but now, in their latest honoured companion, forcefully renewed. These predecessors, disturbed in the long, dreaming serenity of Poets’ Corner and their ‘tradition of the poetic character as something high, detached and simple’ by the irruption of Browning, are obliged to measure their marmoreal greatness against Browning’s irreverent inversions and subversions that blew the spark of life into those poetic traditions. But death diminishes the force and power of any great man until—James observed—‘by the quick operation of time, the mere fact of his lying there among the classified and protected makes even Robert Browning lose a portion of the bristling surface of his actuality’. The stillness of silence and marble smooths out the poet and his work. The Samson who would crack the pillars of poetry is subsumed into the fabric of Poets’ Corner, of the Abbey, and of an Englishness that eventually, by force of the simplicity of its legends and the ineffable character of its traditions, stifles the vitality of the poet’s words and corrupts the subtle colours of their maker.

‘Victorian values’ has become a loaded phrase in recent times, sometimes revered, sometimes reviled. At best, the epithet for an age has provoked a revived interest not only in eminent Victorians but also, perhaps more so, in their ethical beliefs and social structures—though in our current perceptions those values are often misunderstood and misinterpreted when set against present-day values, which in turn are too often misapprehended by interested parties seeking to adapt them to their particular advantage and to the confusion of their opponents. Henry James gives the cue when he states that Robert Browning was a modern. Browning survives in the ‘great tradition’ as a ‘modern’ and, in his earlier life, he suffered for it. Matthew Arnold characterized Browning’s poetry as ‘confused multitudinousness’, and at first sight it is often bewildering. To cite the rolling acres of verse, the constantly (though not deliberately) obscure references, the occasional archaisms, is but to highlight a few surface difficulties.

To anyone unfamiliar with or still unseized by Robert Browning, his reputation as a serious, intellectual, difficult, and prolific writer is an impediment to reading even the most accessible of his poems. To the extent that he was serious—as he could be—he was serious because of his insistence on right and justice and the honest authenticity of his own work. To the extent that he was intellectual, he confounded even the most thoughtful critics of his day, and only now, with the perspective of time that enables more objective critical understanding of Victorian themes and thought, can his poetry be more deeply appreciated. To the extent that he was difficult, he was difficult because of his paradoxical simplicity. To the extent that he was prolific—well, he had a great deal to say on a great number of ideas and ideals, themes and topics.

The length of much of Browning’s poetry is daunting. The attention span of modern readers is supposedly more limited than that of the Victorians, though even the attention of the most persistent, discriminating intellects of the literary Victorians was liable to flag: George Eliot, noting advice to confine her own poetic epic, The Spanish Gipsy, to 9,000 lines, remarked in a letter of 1867 to John Blackwood, ‘Imagine—Browning has a poem by him [The Ring and the Book] which has reached 20,000 lines. Who will read it all in these busy days?’ The diversity, too, is intimidating: ‘You have taken a great range,’ remarked Elizabeth Barrett admiringly, ‘from those high faint notes of the mystics which are beyond personality—to dramatic impersonations, gruff with nature.’

To understand Henry James’s assertion that Browning was ‘a tremendous and incomparable modern’, it is necessary to understand the Victorian world as modern, as a dynamic, experimental, excitingly innovative age of achievements in exploration (internal and external) and advances in invention, but also as a time of doubts raised by experiments and enquiries. Browning himself is a prime innovator, an engineer of form, an explorer of history and the human heart, revolutionary in his art and of lasting importance in his achievements. One critic has suggested that Browning’s masterpiece, The Ring and the Book, may be viewed as a ‘heroic attempt to fuse Milton with Dickens, the modern novel with the epic poem’. Certainly, the comparison with Dickens is sustainable: Browning’s poetry is conspicuously democratic, rapid, colloquial, and modern in its preoccupation with individuals and the social, religious, and political systems in which they find themselves obliged to struggle, to progress throughout the history of humanity’s efforts to develop.

Words like ‘develop’ and ‘progress’ raise the matter of Browning’s optimism, which is usually taken at face value to mean his apparently consoling exclamations on the level of ‘God’s in his heaven—All’s right with the world’, ‘Oh, to be in England/Now that April’s there’, ‘Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp/Or what’s a heaven for?’, and so on. These are positive enough, and over-familiar to those who seek moral, theological, or nationalistic uplift from Browning. They have become the stuff of samplers and poker-work, tag lines expressive of a pious sentimentality (‘It was roses, roses all the way …’) he rarely intended, a jingoistic English nationalism (‘Oh, to be in England …’) he hardly felt, and a shining Candidean optimism (‘God’s in his heaven …’) that was the least of his philosophy. Browning’s poetry too often survives miserably as useful material to be raided and packaged for books of inspirational verse-in-snippets and comfortable quotations. This is a permanent fame, perhaps, but not Parnassian glory.

Browning’s optimism was a more robust and muscular characteristic, deriving not at all from sweet-natured sentimentality or rose-tinted romanticism. Rather, it was rooted in a profound, passionate realism—naturalism, some claim—and tremendous psychological analysis that looked unsparingly, with a clear eye, at the roots and shoots of good and evil. Unlike most Victorians, Robert Browning was more matter-of-factly medieval or ruthlessly Renaissance in his assessments and acceptance of matters from which fainter, or at least more emollient, spirits retreated and who drew a more or less banal moral satisfactory to the pious, who tended to prefer the possibility of redemption through suffering. For some readers, suffering was quite sufficient in itself—a just reward and retribution for the sin or moral failure, for example, of being poor.

Browning’s innate Puritanism, as Chesterton remarks, stood him in good stead, providing a firm foothold ‘on the dangerous edge of things’ while he investigated ‘The honest thief, the tender murderer.’ The early attempts of the Browning Society and others to construct a ‘philosophy’ for Browning, a redeeming and inspirational theological and ethical system to stand as firmly as that imposed by Leslie Stephen on Wordsworth, is bound to be suspect in specifics and should be distrusted in general.

That Browning was a lusty optimist is rarely doubted in the popular mind, but the evidence adduced to support the theory is too often selective and superficial. His optimism was in fact an appetite and enthusiasm for life in all its aspects, inclusive rather than exclusive, from the highest joy to the darkest trials. His optimism was an expression of endurance, of acceptance, of the vitality of living and loving, of finding value in the extraordinary individuality and oddity of men and women. Robert Browning is, in the judgement of G. K. Chesterton, ‘a poet of misconceptions, of failures, of abortive lives and loves, of the just-missed and the nearly fulfilled: a poet, in other words, of desire’. Ezra Pound insists on Browning’s poetic passion. Men and Women, the collection of poems that redeemed Browning from obscurity in middle-age, is a demotic, democratic piece of work that reflects his distance from his early reliance on the remote Romantic imagery of Shelley and adopts a firmer insistence on the mundane life of city streets and market-places.

This interest in the apparently tawdry, temporal life of fallible men and women somewhat disconcerted his more elevated, intellectual contemporaries. Of The Ring and the Book, George Eliot (who should have known better, and might have had more sympathy for the poem in her youth) commented: ‘It is not really anything more than a criminal trial, and without anything of the pathetic or awful psychological interest which is sometimes (though very rarely) to be found in such stories of crime. I deeply regret that he has spent his powers on a subject which seems to me unworthy of them.’ She was not the only contemporary critic to make such a point, or adopt such an aesthetic view: Thomas Carlyle declared the poem to be ‘all made out of an Old Bailey story that might have been told in ten lines and only wants forgetting’.

In short, Browning shocked his contemporaries. The shock consequent on his choice of subject matter was perhaps compounded by the novelty of his poetic approach to its treatment. Pippa Passes, startlingly unlike in form to anything contemporaneous in English poetry, is regarded by Chesterton, aside from ‘one or two by Walt Whitman’, as ‘the greatest poem ever written to express the sentiment of the pure love of humanity’. Like Whitman, Browning was responsive to the spirit of his age. For all his learning and his familiarity with the past, and for all his choice of antique subject matter and foreign locations, Browning is no funeral grammarian of a past culture, of spent history. His portrait of the Florentine artist Fra Lippo Lippi is as living, as vibrant, and as relevant as might be a current account of the life of the modern painters Francis Bacon or Damien Hirst. The speeches in The Ring and the Book might, with some adjustments, make a modern television or radio series examining a murder case from the points of view of all the protagonists. The form of serial views of one event was not new when Browning revived it from Greek classic models, but he infused it with modernity and it has since become a staple model for dramatists.

Browning did not bestride the peaks of poetry like a Colossus with a lofty and noble eye for the prospect at his feet. He rambled like a natural historian, peering and poking in holes and corners, describing minutely and drawing his particular conclusions; he visited the courtroom with a reporter’s notebook, and the morgue with the equipment of a forensic scientist. He was an entomologist of humanity in all its bizarre conditions of being. His great subjects were philosophy, religion, history, politics, poetry, art, and music—a few more than even Ezra Pound later marked out as the fit and proper preoccupations of serious poetry. They were all encompassed in Browning’s studies of modern society and the men and women of a universal humankind.

Browning’s poetry is often of a period, but in no sense is it period poetry, nor is Browning a period poet. In this he differs from the more consciously archaic writers and works of the Pre-Raphaelites who admired him, strove to imitate him, and embedded themselves in a literary aspic. Whereas his successors became conscious, perhaps dandified and decadent, Browning himself was largely and serenely unconscious, vigorous, and often matter-of-fact. He had principles and opinions, at first devoutly and latterly didactically held. But Browning was learned and assimilative rather than rigorously intellectual. His poetry suffers often from obscurities that puzzle intellectuals because Browning was, above all, a widely and profoundly literate, well-read man.

Once he had absorbed a fact or a thesis, he subsumed it in his mind where it found useful and congenial company. Joined with a mass of other facts and theses, it became so inextricably enmeshed with its fellows that, when it was eventually pulled out to illustrate, embellish, or point up a phrase in Browning’s work, it was comprehensible only—though not always afterwards, when he had done with it—to the mind of the poet. Being already so personally familiar with it, he thought nothing of its unfamiliarity to his readers. Chesterton regards this as the greatest compliment he could have paid the average reader. There are many who may feel too highly complimented. In this sense, his poetry is devoid of intellectual arrogance or one-upmanship. Perfectly innocently and without conscious affectation, Browning’s work arises from and is coloured with what Henry James identified as an ‘all-touching, all-trying spirit … permeated with accumulations and playing with knowledge’.

For all his modernity, now increasingly acknowledged and admired by literary critics, Browning has recently been somewhat neglected by literary biographers. ‘What’s become of Waring?’ is a well-known line from one of his best-known poems. What, one may reasonably ask, has become of Browning? There is no lack of interest in him in one sense—in the sense of Robert Browning as one half of that romantic pair, the Brownings. The marriage of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning remains a perennially seductive subject, and not only for biographers. One difficulty for the modern biographer is that Robert Browning’s reputation has never quite lived down being cast as a great romantic hero, the juvenile lead, as it were, in Rudolph Besier’s 1934 stage play The Barretts of Wimpole Street and subsequently in the Hollywood movie, where Robert Browning was played dashingly and dramatically by Fredric March. This has become his principal claim to popular fame. For various reasons, Robert has become the dimmer partner, Elizabeth the brilliant star. The romantic hero of fiction or drama is, in any case, generally only a foil for the romantic heroine.

There are big modern biographies of most of Browning’s contemporaries, and more are published every year, but Browning himself is comparatively unknown to present-day readers. Elizabeth Barrett Browning is, to be realistic, the more immediately colourful and engaging character—the drama of her early years as a supposed invalid, the romance of her marriage to Robert Browning and their escape to Italy, the currently fashionable interest in her as an early feminist and as a radical in terms of her views on politics and social justice. Her husband, by contrast, is perceived as a more reactionary and conventional, a more prudish and private character. If judged solely by the quantity and quality of their letters to friends and acquaintances, his personality is less immediately engaging, and, for all his superficial sociability, more introverted and private.

In contrast to the relative scarcity of biographies of Robert Browning, there is an astonishing quantity of critical monographs and papers hardly penetrable to any but the Browning academic specialist. What has recently been lacking, is a chronological narrative of Browning’s life as an upstage drama to complement the downstage chorus of critics of his work. This present book is a conventional, chronological biography of Browning. Despite the enormous and constant critical attention paid to Browning, and the number of books about Elizabeth Barrett Browning and the marriage of the Brownings, there have been few modern biographies that give themselves over mostly to the life and character of the man himself.

The standard late twentieth-century biography of Robert Browning that confidently, authoritatively, and entertainingly treats his life as thoroughly as his poetry is The Book, the Ring, and the Poet by William Irvine and Park Honan, published in 1974. Robert Browning: A life within life, Donald Thomas’s biography, published in 1982, is the conscientious work of a scholar who combines a life of the poet with critical analysis of his work. Clyde de L. Ryal’s 1993 biography, The Life of Robert Browning, is an attractive, authoritative literary critical work that provides an overview of Browning’s life and work as a bildungsroman without the distraction of—for the purposes of his book—unnecessary domestic detail.

In this present biography, I have of course been heedful of as much recent biographical work on Browning as seemed to me relevant to my purposes—specific references are gratefully (and comprehensively, I hope) acknowledged—but I have not neglected earlier biographies in my search for such materials as Nathaniel Hawthorne might have characterized as the ‘wonderfully and pleasurably circumstantial’.

A principal resource for any Browning biographer must be the official Life and Letters of Robert Browning (1891) by Mrs Alexandra Sutherland Orr, a close friend of the poet. Mrs Orr wrote her biography at the request of Browning’s son and sister. Besides the obvious constraints of these two interested parties at her shoulder, she was writing, too, soon after Browning’s death, as a close friend as much as a conscientious critic. She is thus, and naturally, tactful. Though she is not deliberately misleading, nevertheless she will occasionally suppress materials when she considers it discreet to do so, and will sometimes turn an unfortunate episode to better, more positive account than we might now consider appropriate. A close, long-standing friend of Browning’s, William Wetmore Story, supplied Mrs Orr with details of their long friendship. On reading the published biography in 1891, he commented that it seemed rather colourless, but admitted that Browning’s letters ‘are not vigorous or characteristic or light—and as for incidents and descriptions of persons and life it is very meagre’. Subsequent biographers have supplied the deficit.

My second principal biographical authority is Gilbert Keith Chesterton, whose short book about Browning, published in 1903, is valuable less for strict biographical fact, which now and again he gets wrong, than for consistently inspired and constantly inspiriting psychological judgements about the poet and his work, which he gets right. Like Mrs Orr, Chesterton’s value is that he was closer in time and thought to the Victorian age, more attuned to the Browning period and the psychology of the protagonists than we are now, closer to the historical literary ground than we can be. Chesterton’s Robert Browning has never been bettered. It remains unarguably perceptive and uniquely provocative. Besides its near-contemporaneity to its subject, Chesterton’s book is valuable because it evokes Browning’s character with the very ironies and psychological inversions that Browning himself often employed in his poetry. Time and again Chesterton proposes the converse to prove the obverse, exactly as Browning could easily—with poetic prestidigitation—prove black to be white or red.

Two lively, thoughtful women—Betty Miller and Maisie Ward—have contributed more recent biographies that sometimes convincingly and sometimes controversially propose psychological and psychoanalytic interpretations of Robert Browning, his poetry, and his life. Their insights are regularly disputed, and perhaps for that very reason they regularly startle their readers out of complacency. They ask questions, raise points, that—right or wrong—are still worth serious consideration by Browning’s critics and biographers.

I should also say that I have generally relied on earlier Browning criticism, which retains much of its vigour and sparky originality. This is by no means to belittle latter-day critics, many of whom write ingeniously and excitingly, but merely to indicate that for the purposes of this biography I have for the most part personally preferred period sources and contemporary authorities. An exception has to be made for The Courtship of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett, Daniel Karlin’s close and authoritative study of the love-letters that preceded the marriage. This book is indispensable to any modern biographer of Browning, not just for Karlin’s detailed analysis of the voluminous correspondence but also for the tenderness and imagination he brings to its interpretation.

There is—or has been—a discussion about how far the biography of an objective poet is necessary, in contrast to the permissible biography of a subjective poet. Browning gave his own views on this in his essay on Shelley. Since Browning himself is generally reckoned to combine subjective and objective elements in his work, then it probably follows that a biography detailing the day-to-day activities of the poet may be as relevant as a critical commentary on his poetry. G. K. Chesterton remarked that one could write a hundred volumes of glorious gossip about Browning. The Collected Letters of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, when the full series is finally published, will be exactly that. But for all the froth and bubble of Browning’s social life, not a great deal happened to him—there is a distinct dearth of dramatic incident. One is inclined to sigh with relief, like Joseph Brodsky who says of Eugenio Montale, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1975 for the poetry he had written over a period of sixty quiet years, ‘thank God that his life has been so uneventful’.1