Полная версия

Franco

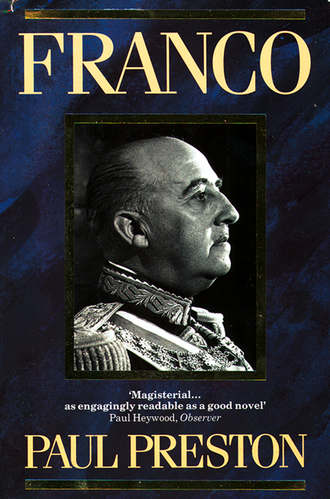

Two days after the successful ‘victory convoy’, Franco flew to Seville and established his headquarters in the magnificent palace of the Marquesa de Yanduri.85 Marking a clear distinction with Queipo’s more modest premises, the palace’s grandeur revealed more about Franco’s political ambitions than his military necessities. He began to use a Douglas DC-2 to visit the front or travel to meet Mola for consultations.86 In Seville, he began to gather around him the basis of a general staff. Apart from two ADCs, Pacón and an artillery Major Carlos Diaz Varela, there were Colonel Martín Moreno, General Kindelán and, a recent arrival, General Millán Astray.87 This reflected the fact that finally he had an army on the move.

Even before the ‘victory convoy’, Franco had already, on 1 August, ordered a column under the command of the tough Lieutenant-Colonel Carlos Asensio Cabanillas to occupy Mérida and deliver seven million cartridges to the forces of General Mola. The column had set out on Sunday 2 August in trucks provided by Queipo de Llano and advanced eighty kilometres in the first two days. Facing fierce resistance from untrained and poorly armed Republican militiamen, they took another four days to reach Almendralejo in the province of Badajoz. Asensio’s column had been followed on 3 August by another column led by Major Antonio Castejón which had advanced somewhat to the east and on 7 August by a third under Lieutenant-Colonel Heli Rolando de Tella. Franco telegrammed Mola on 3 August to make it clear that the ultimate goal of these columns was Madrid. After the frenetic efforts of the previous two weeks to secure international support and get his troops across the Straits, Franco’s mood was euphoric.

Franco placed Yagüe in overall field command of the three columns. He ordered them to make a three-pronged attack on Mérida, an old Roman town near Cáceres, and an important communications centre between Seville and Portugal. The columns advanced with the Legionaires on the roads and the Moorish Regulares fanning out on either side to outflank any Republican opposition. With the advantage of local air superiority provided by Savoia-81 flown by Italian Air Force pilots and Junkers Ju-52 flown by Luftwaffe pilots, they easily took villages and towns in the provinces of Seville and Badajoz, El Real de la Jara, Monesterio, Llerena, Zafra, Los Santos de Maimona, annihilating any leftists or supposed Popular Front sympathisers found and leaving a horrific trail of slaughter in their wake. The execution of captured peasant militiamen was jokingly referred to as ‘giving them agrarian reform’. After the capture of Almendralejo, one thousand prisoners were shot including one hundred women. Mérida fell on 10 August. In a little over a week, Franco’s forces had advanced 200 kilometres. Shortly afterwards, initial contact was made with the forces of General Mola.88 Thus, the two halves of rebel Spain were joined into what came to be called the Nationalist zone.

The terror which surrounded the advance of the Moors and the Legionaries was one of the Nationalists’ greatest weapons in the drive on Madrid. After each town or village was taken by the African columns, there would be a massacre of prisoners and women would be raped.89 The accumulated terror generated after each minor victory, together with the skill of the African Army in open scrub, explains why Franco’s troops were initially so much more successful than those of Mola. The scratch Republican militia would fight desperately as long as they enjoyed the cover of buildings or trees. However, they were not trained in elementary ground movements nor even in the care and reloading of their weapons. Thus, even the rumoured threat of being outflanked by the Moors would send them fleeing, abandoning their equipment as they ran.90 Franco was fully aware of the Nationalists’ superiority over untrained and poorly armed militias and he and his Chief of Staff, Colonel Francisco Martín Moreno, planned their operations accordingly. Intimidation and the use of terror, euphemistically described as castigo (punishment), were specified in written orders.91

Given the iron discipline with which Franco ran military operations, there is little possibility that the use of terror was merely a spontaneous or inadvertent side effect. There was little that was spontaneous in Franco’s way of running a war. On being informed of the bravery of a group of Falangist militiamen in capturing some Republican fortifications, Franco ordered them to be shot if they ever again contravened the day’s orders, ‘even though I have to go and place the highest decorations on their coffins’.92 In late August, Franco boasted to a German emissary of the measures taken by his men ‘to suppress any Communist movement’.93 The massacres were useful from several points of view. They indulged the blood-lust of the African columns, eliminated large numbers of potential opponents – anarchists, Socialists and Communists whom Franco despised as rabble – and, above all, they generated a paralysing terror.

He wrote Mola on 11 August an extraordinarily significant letter, revealing his expectations of a quick end to the war, his strategic vision and the colonial mentality behind his views on the conquest of territory. He agreed that the priority should be the occupation of Madrid but stressed the need to annihilate all resistance in the ‘occupied zones’, especially in Andalusia. Franco mistakenly assumed that the early capture of Madrid would precede attacks on the Levante, Aragón, the north and Catalonia. He suggested that Madrid be squeezed into submission by ‘tightening a circle, depriving it of water supplies and aerodromes, cutting off communications’. Crucially, in the light of his later remarkable diversion of troops away from Madrid, he ended with the words: ‘I did not know that [the Alcázar of] Toledo was still being defended. The advance of our troops will take the pressure off and relieve Toledo without diverting forces which might be needed’.94

At the time that Franco’s letter was being written, Mola was complaining about the difficulties of liaison.95 Telephone contact between Seville and Burgos was established immediately after the capture of Mérida. The two generals spoke on 11 August. Apparently oblivious to any eventual political implications, Mola agreed with Franco that there was no point duplicating his successful international contacts and therefore ceded to him the control of supplies. Mola’s political allies were appalled at his naïvety. José Ignacio Escobar asked him if he had therefore agreed on the telephone that the head of the movement be Franco. Mola replied guilelessly, ‘It is an issue which will be resolved when the time comes. Between Franco and I there are neither conflicts nor personal ambitions. We see entirely eye-to-eye and to leave in his hands this business of the procurement of arms abroad is just a way of avoiding a harmful duplication of effort.’ When Escobar insisted that this made Mola the second-in-command as far as the Germans were concerned, he brushed aside his remarks. The control of arms supplies guaranteed that Franco and not Mola, with all the attendant political implications, would dominate the assault on the capital.96

After the occupation of Mérida, Yagüe’s troops turned back south-west towards Portugal to capture Badajoz, the principal town of Extremadura, on the banks of the River Guadiana near the Portuguese frontier. Although encircled, the walled city was still in the hands of numerous but ill-armed left-wing militiamen who had flocked there before the advancing Nationalist columns. Many were armed only with scythes and hunting shotguns. Most of the regular troops garrisoned there had been called away to reinforce the Madrid front.97 If Yagüe had pressed on to Madrid, the Badajoz garrison could not seriously have threatened his column from the rear. It has been suggested that Franco’s decision to turn back to Badajoz was a strategic error, contributing to the delay which allowed the government to organize its defences. Accordingly, Nationalist historians have blamed Yagüe but the decision smacks of Franco’s caution rather than Yagüe’s frenetic impetuousness. Franco made all the major daily decisions merely leaving their implementation to Yagüe. He had personally supervised the operation against Mérida and, on the evening of 10 August, received Yagüe in his headquarters to discuss the capture of Badajoz and the next objectives.98 He wanted to knock out Badajoz to clinch the unification of the two sections of the Nationalist zone and to cover completely the left flank of the advancing columns.

On 14 August, after heavy artillery and bombing attacks, the walls of Badajoz were breached by suicidal attacks from Yagüe’s Legionarios. Then a savage and indiscriminate slaughter began during which nearly two thousand people were shot, including many innocent civilians who were not political militants. According to Yagüe’s biographer, in ‘the paroxysm of war’, it was impossible to distinguish pacific citizens from leftist militiamen, the implication being that it was perfectly acceptable to shoot prisoners.99 The Legionarios and Regulares unleashed an orgy of looting and the carnage left streets strewn with corpses, a scene of what one eyewitness called ‘desolation and dread’. After the heat of battle had cooled, two thousand prisoners were rounded up and herded to the bull-ring, and any with the bruise of a rifle recoil on their shoulders were shot. The shootings went on for weeks thereafter. Yagüe told the American journalist John T. Whitaker, who accompanied him for most of the march on Madrid, ‘Of course, we shot them. What do you expect? Was I supposed to take four thousand Reds with me as my column advanced racing against time? Was I expected to turn them loose in my rear and let them make Badajoz Red again?’.100 In fact, the savagery unleashed on Badajoz reflected both the traditions of the Spanish Moroccan Army and the outrage of the African columns at encountering a solid resistance and, for the first time, suffering serious casualties. In retrospect, it can be seen that the events of Badajoz might have been taken to anticipate what would happen when the columns reached Madrid. The clear lesson was that the easy victories of the Legionarios and Regulares in open country were not replicated in built-up cities. This was not widely perceived in the Nationalist camp but the stiffening of Republican resistance does seem to have dented Franco’s earlier optimism.

The distant cloud of potential difficulties at Madrid could hardly dim Franco’s appreciation of the benefits won at Badajoz. Now, crucially, there was unrestricted access to the frontier of Portugal, the Nationalists’ first international ally. From the beginning, Oliveira Salazar had permitted the rebels to use Portuguese territory to link their northern and southern territories.101 It was access to Portuguese help which, as much as any other factor, had decided Franco to swing his columns westwards through the province of Badajoz rather than the more direct route along the main road from Seville to Madrid, across the Sierra Morena via Córdoba.*102

On 14 August, General Miguel Campins, Franco’s one-time friend and second-in-command at the Academia General Militar de Zaragoza, was tried in Seville for the crime of ‘rebellion’. The court martial was presided over by General José López Pinto. Campins was sentenced to death and shot on 16 August.103 His crime was to have refused to obey Queipo’s demand on 18 July that he declare martial law in Granada and to have delayed two days before joining the rising. Franco was unable to overcome the determination of Queipo de Llano to have Campins shot. According to Franco’s cousin, despite refusing Queipo’s order, Campins had in fact telegraphed Franco putting himself under his orders. Franco wrote a number of letters to Queipo requesting that mercy be shown to Campins. Queipo simply tore them up but Franco did not push the matter further for fear of undermining the unity of the Nationalist camp.104 According to his sister Pilar, Franco was upset by the death of his friend.105 Queipo’s determination to execute Campins despite pleas for mercy reflected both his brutal character and his long-standing loathing of Franco. Franco took his revenge in 1937 by ignoring Queipo’s own pleas for mercy for his friend General Domingo Batet, who was condemned to death for opposing the rising in Burgos.106

While Campins was being tried and shot, Franco made a cunning move which boosted his stock in the eyes of Spanish rightists at the expense of his rivals in the Junta. In Seville on 15 August, flanked by Queipo, he announced the decision to adopt the monarchist red-yellowred flag. Queipo acquiesced cynically, reluctant to draw attention to his own republicanism. Mola, who barely two weeks before had expelled the heir to the throne, was not consulted. Only with acute misgivings did General Cabanellas sign a decree of the Junta de Defensa Nacional two weeks later ratifying the use of the flag.107 Franco had managed to present himself to conservatives and monarchists as the one certain element among the leading rebel generals. It was a clear indication that while the others thought largely of eventual victory, Franco kept a sharp eye on his own long-term political advantage.

In fact, Mola and Franco were worlds apart in both political preferences and in temperament. In the words of Mola’s secretary José María Iribarren, Mola ‘was neither cold, imperturbable nor hermetic. He was a man whose face transmitted the impressions of each moment, whose stretched nerves reflected disappointments’.108 Mola himself seemed totally oblivious to security, strolling around Burgos alone and in civilian clothes. His headquarters were chaotic with visitors wandering in at all times.109 Queipo de Llano was equally casual about visitors. In contrast, Franco had a bodyguard and the tightest security arrangements at his headquarters. Visitors were searched thoroughly and during interviews with Franco, the door was kept ajar and one of the guards kept watch via a strategically placed mirror.110

Those who did get in to see him did not find a daunting war lord. Many aspects of Franco’s demeanour, his eyes, his soft voice, the apparent outer calm struck many commentators as somehow feminine. John Whitaker, the distinguished American journalist, described him thus: ‘A small man, his hand is like a woman’s and always damp with perspiration. Excessively shy, as he fences to understand a caller, his voice is shrill and pitched on a high note which is slightly disconcerting since he speaks very softly – almost in a whisper.’111 The femininity of Franco’s appearance was frequently, and inadvertently, underlined by his admirers. ‘His eyes are the most remarkable part of his physiognomy. They are typically Spanish, large and luminous with long lashes. Usually they are smiling and somewhat reflective, but I have seen them flash with decision and, though I have never witnessed it, I am told that when roused to anger they can become as cold and hard and steel.’112

Franco certainly had heated arguments in Seville with Queipo de Llano who had difficulty concealing his contempt for the man who was below him in the seniority scale. In contrast, Mola remained on good terms with Franco.113 A German agent reported to Admiral Canaris in mid-August on the view from Franco’s headquarters. The report showed the wily gallego subtly consolidating his position and confirming the fears of Mola’s supporters that he had sold the pass to Franco on 11 August. The agent’s report stated that German aid must be channelled through Franco.114 Mola continued to recognize Franco’s superior position in terms of foreign supplies and battle-hardened troops. Their correspondence in August shows Franco as the distributor of largesse in terms of financial backing and military hardware. Franco could boast of the fact that foreign suppliers made few if any demands upon him in terms of early payment. He could offer to send Mola aircraft.115

On 16 August, Franco, accompanied by Kindelán, flew to Burgos where Mola could not have failed to notice the manic fervour with which his comrade was received by the local population. A solemn high mass was said in the Cathedral by the Archbishop.116 At dinner that night, Franco’s optimism about the progress of the war was as unshakeable as ever. The only glimmer of anxiety came in a comment to Mola that he was worried that he had had no news of his wife Carmen and his daughter Nenuca.117 After dinner, Franco and Mola spent several hours locked in secret conclave. Although no decision was taken, it was obvious to both of them that the efficient prosecution of the war required a single overall military command.118 It was obvious too that some kind of centralised diplomatic and political apparatus was necessary. Franco and his small staff were working ceaselessly to maintain foreign logistical support. The Junta de Burgos which used to meet late at night was also finding itself overwhelmed with work.119 Given Franco’s near monopoly of contacts with the Germans and Italians and the apparently unstoppable progress of his African columns, Mola must have realized that the choice of Franco to assume the necessary authority would be virtually inevitable. Franco’s staff had already loaded the dice by convincing German Military Intelligence that the victory in Extremadura had indisputably established him as ‘Commander-in-Chief’. Portuguese newspapers and other sections of the international press described him as ‘Commander-in-Chief’ presumably on the basis of information supplied by his headquarters. The Portuguese consul in Seville referred to him as ‘the supreme commander of the Spanish Army’ as early as mid-August.120

Mola was gradually being forced towards the same view. On 20 August, he sent a message to Franco pointing out his own troops were having difficulties on the Madrid front and asking to be informed of Franco’s plans for his advance on the capital. In the event of Franco’s advance being delayed Mola would make arrangements to concentrate his activities on another front.121 The text of his telegram suggested less a deferential subordination to Franco’s greater authority than a rational desire to co-ordinate their efforts in the interests of the war effort. Mola was not thinking in terms of a power struggle but three days later he was brutally made aware of the extent to which Franco was consolidating his own position. On 21 August, Mola received a visit from Johannes Bernhardt in Valladolid. Bernhardt came with the good news that an anxiously awaited German shipment of machine-guns and ammunition was on its way by train from Lisbon. Mola’s delight was severely diminished when Bernhardt said to him ‘I have received orders to tell you that you are receiving all these arms not from Germany but from the hands of General Franco’. Mola went white but quickly accepted the inevitable. It had already been agreed with General Helmuth Wilberg, head of the inter-service commission sent by Hitler to co-ordinate Unternehmen Feuerzauber, that German supplies would be sent only on Franco’s request and to the ports indicated by him.122

After the capture of Badajoz, Yagüe’s three columns had begun to advance rapidly up the roads to the north-east in the direction of the capital. Tella’s column had moved to Trujillo on the road towards Madrid while Castejón’s column had raced towards Guadalupe on Tella’s southern flank. By 17 August, Tella had reached the bridge across the Tagus at Almaraz and shortly afterwards arrived at Navalmoral de la Mata on the borders of the province of Toledo. Castejón’s column would capture Guadalupe on 21 August. Castejón, Tella and Asensio would join together on 27 August before the last town of importance on the way to Madrid, Talavera de la Reina. In two weeks, they had advanced three hundred kilometres.123

Despite these heady successes, Franco’s telegram in reply to Mola suggested that his unflappable optimism was beginning to be eroded by Republican resistance. He made it clear that, on the advance to Talavera de la Reina, he feared strong Republican flank attacks at Villanueva de la Serena and Oropesa. ‘A well-defended town can hold up the advance. I’m down to six thousand men and have to guard long lines of communication. Flank attacks limit my capacity for movement.’ He outlined to Mola the next stages of the push, on to the important road junction at Maqueda in Toledo, then from Maqueda diagonally north-east to Navalcarnero on the road to Madrid.*124 Within a month, the bold and direct strategy outlined to Mola would be abandoned in the interests of ensuring that Franco would be the undisputed Generalísimo.

* Antonio Goicoechea, the head of Renovación Española, the intellectual Pedro Sáinz Rodríguez, the Conde de Vallellano, José Ignacio Escobar, owner of the monarchist newspaper La Época, the lawyer José María de Yanguas y Messía and Luis María Zunzunegui.

* German equipment would be imported to Spain by the Compañía Hispano-Marroquí de Transportes (HISMA) set up on 31 July by Franco and Berhardt and Spanish raw materials imported into Germany by the Rohstoffe-und-Waren-Einkaufsgesellschaft (ROWAK) created on 7 October 1936 at the initiative of Marshal Göring.

* Alfonso XIII’s eldest son, Alfonso, was afflicted by haemophilia and had formally accepted the loss of his right to the throne in June 1933 when he contracted a morganatic marriage with Edelmira Sampedro, the daughter of a rich Cuban landowner. The King’s second son, Jaime, immediately renounced his own rights on the grounds of a disablement (he was deaf and dumb). Jaime would, in any case, have lost his rights when, in 1935, he also married morganatically an Italian, Emmanuela Dampierre Ruspoli, who although an aristocrat was not of royal blood. Alfonso died in September 1938 after a car crash in Miami.

* Assuming that Franco would attack through Cordoba, and believing the Yagüe columns to be engaged only in local operations, the Republican General Miaja had concentrated his exiguous defensive forces on the Córdoba-Madrid line.

* The Francoist military historian, Colonel José Manuel Martínez Bande, has seen this message as the first sign of Franco’s decision to relieve the Alcázar de Toledo. His view is based entirely on the presence in the message of the words: ‘Maqueda-Toledo’, which he arbitrarily takes to mean ‘relief of the Alcázar’. However, the rest of Franco’s text shows rather that after Maqueda the column would make a continued thrust to Madrid in a direct line to Navalcarnero rather than make any diversion to Toledo.

VII

THE MAKING OF A CAUDILLO

August – November 1936

THE SUCCESSES of the African columns and the imminent attack on Talavera led, on 26 August, to Franco transferring his headquarters from Seville to the elegant sixteenth century Palacio de los Golfines de Arriba in Cáceres. He was anxious to move on from Seville in order to establish his total autonomy, free from the interference or disdain of Queipo de Llano in whose presence he always felt uncomfortable.1 Like his earlier choice of the Palacio de Yanduri in Seville, it indicated a jealous concern for his public status. Franco was beginning to build a political apparatus capable of daily dealings with the Germans and Italians. Already he had a diplomatic office, headed by José Antonio de Sangróniz. Lieutenant-Colonel Lorenzo Martínez Fuset acted as legal adviser and political secretary. Franco was also accompanied from time to time by his brother Nicolás, who travelled between Cáceres and Lisbón where he was working for the Nationalist cause. Nicolás would soon be acting as a kind of political factotum. Millán Astray was in charge of propaganda. Even at this early stage, the tone of Franco’s entourage was sycophantic.2

The sheer volume of work facing Franco, effectively co-ordinating Nationalist ‘foreign policy’ and logistical organization, as well as maintaining close overall supervision of the advance of the African columns, obliged him to work immensely long hours. His resistance to discomfort and the powers of endurance which he had displayed as a young officer in Africa were undiminished but he began to age noticeably. The manic Millán Astray boasted to Ciano that ‘our Caudillo spends fourteen hours at his desk and doesn’t get up even to piss’.3 When his wife and daughter returned to Spain after their two-month exile in France – on 23 September – he responded to the announcement of their arrival by sending them a message that he had important visitors waiting. They were obliged to wait for more than an hour. He had little time for family life.4 Such concentration and strain perhaps contributed to the quenching of his early optimism but the re-emergence of a cautious Franco after the brief reincarnation of the impetuous African hero denoted both the prospect of power and the growing strength of Republican resistance.