Полная версия

After the Funeral

Agatha Christie

AFTER

THE

FUNERAL

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by

Collins 1953

Copyright © 1953 Agatha Christie Ltd.

All rights reserved.

www.agathachristie.com

The moral right of the author is asserted

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007562695

Ebook Edition 2010 ISBN: 9780007422128

Version: 2018-09-26

For James

in memory of happy days

at Abney

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

After the Funeral: An introduction by Sophie Hannah

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

E-book Extra: The Poirots

The Monogram Murders

About Agatha Christie

The Agatha Christie Collection

About the Publisher

After the Funeral: An Introduction by Sophie Hannah

In a poll conducted by the Crime Writers’ Association in November 2013 to celebrate its sixtieth anniversary, Agatha Christie was voted ‘Best Ever Author’. Any other result would, frankly, have been rather a joke. Christie’s novels have sold more than two billion copies in 109 languages (and probably more). Her play The Mousetrap has been delighting audiences in the West End for over 60 years. It would be fair to say, I think, that no other crime novelist comes close to matching her achievement. For me, as a psychological thriller writer, Agatha Christie is and will always be the gold standard—a lifelong inspiration whose every inventive tale demonstrates exactly how it should be done. It was Christie who made me fall in love with mystery stories at the age of twelve and, rereading her work now at the age of 42, I still believe that she cranks up the excitement and the intellectual puzzlement like no other.

In the ‘Best Ever Novel’ category of the Crime Writers’ Association poll, Christie won again, with a story that many of her fans believe to be her best: The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Indeed, it is a deserving winner for the boldness of its solution. Interestingly, the most popular Christie novels tend to be the ones with the high-concept seemingly-impossible- yet-possible solutions, the ones that take your breath away: The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, And Then There Were None, Murder on the Orient Express. It’s easy to see why this might be. Christie, when conceiving these stories, gave her readers exactly what they wanted: the best story possible, the one most likely to elicit gasps of shock and astonishment when the genius solution is revealed at the end.

Sensibly, Christie didn’t give a damn about the tedious consideration of ‘Come on, how likely is this to happen, really?’ So long as it could happen in theory—as long as no law of science made it impossible—then she quite rightly deemed it to be plausible, and therefore acceptable fodder for fiction. She would, I suspect, have little sympathy for those contemporary readers who determinedly misunderstand the word ‘plausible’ and use it as if it were synonymous with ‘commonplace’, ‘everyday’ or ‘has happened to several people I know personally’.

I say ‘contemporary readers’ because I think our expectations of novels have changed. While Christie was alive and writing, my impression is that most readers of crime fiction shared her philosophy of ‘above all else, tell the most exciting story that you can’. Now, however, a far greater value is placed upon what many insist on calling ‘plausibility’ but what is in fact a worrying lack of imagination seeking to curtail the imaginations of others. Many, for example, might feel uncomfortable with a super-clever detective like Hercule Poirot, who always gets the right answer and proves himself over and over again to be a man of unparalleled genius. Some—having met no unparalleled geniuses themselves and therefore finding them impossible to believe in—might say, ‘No, this is not realistic—can’t you have the detective being a bit more ordinary in his capabilities, and maybe solving the case by… oh, I don’t know, maybe putting some fingerprints into the database and finding a match?’

Let’s imagine for a second that infallibly brilliant detectives like Poirot and Miss Marple could never exist in real life. Wouldn’t it then be all the more important to invent them? To use fiction as a way of enlarging life—making it bigger, better, more interesting, and—crucially—more satisfactory? Of course there has to be a Hercule Poirot! Isn’t it precisely the job of fiction to offer us what real life cannot, while at the same time enlightening us with regard to real life? If so, then this is exactly what Agatha Christie does. Her novels are packed with wisdom and experience and psychological insight. She understood that sometimes the best way to illuminate an important truth about reality was to frame it in a startlingly unusual way, using an outlandish, unforgettable story that would grab everyone’s attention.

Christie didn’t only tell great stories, however. Her true genius was to convey the story, once she’d come up with it, with palpable relish and irrepressible glee. When you read an Agatha Christie novel, you get a strong sense, all the way through, of how thrilled she is by the clues she’s strewn across your path for you to misinterpret or ignore. You can feel her presence behind the text, laughing and thinking, ‘Tee hee! You’re never going to get there before me—I’ve been too clever for you again!’

Christie’s tangible love of storytelling is not her only unique feature as a crime writer. She also manages to combine light and dark, without either of them ever detracting from the other, in a way that no other writer can. Her stories are in no way cosy or twee, though some of their village settings might be; she understands the depravity, ruthlessness and dangerous weakness of human beings. She knows all about warped minds, long grudges, agonising need; in each of her novels, a familiarity with the darkest parts of the human psyche underpins the narrative. Yet at the same time, on the surface of her stories there is fun, lightness, warmth, a puzzle to make readers say, ‘Ooh, this is a good challenge!’ The dark side of Christie’s work never undermines the feel-good effect in any way— reading an Agatha Christie novel is, above all else, great fun.

In September 2013, I was commissioned by Agatha Christie’s estate, family and publishers to write a new Hercule Poirot novel as a way of celebrating the character’s longevity on the printed page. As part of the publicity for the announcement, I was asked to name my favourite novel featuring Poirot. This was a tricky question to answer. I knew for certain that my favourite Miss Marple novel was Sleeping Murder—that was easy!—but with Poirot I wasn’t sure. I have a very soft spot for Murder on the Orient Express because I believe it has the best mystery-and-solution package of all detective fiction. However, when I thought about the Poirot stories as fullbodied novels and not simply as plot structures, I ended up deciding that After the Funeral was my favourite.

After the Funeral has a brilliant plot, meticulously planted clues, a memorably dysfunctional family at its centre, and a truly ingenious solution, but it also has something else that I prize highly: the non-transferable motive. Poirot is forever telling Hastings that motive is the most important feature of a crime, and I agree with him. A non-transferable motive is something that no other murderer in no other crime novel has ever had or would ever have—a motive that is unique to this character in this particular fictional situation. With a non-transferable motive, the reader should ideally think, ‘Well, although I would never commit murder for this reason, I can absolutely understand why this character did—it makes perfect sense because of their unique personality/predicament combination.’ On this score, After the Funeral works in the most superb way. It also does something else very clever on the motive front—it offers us a two-layer motive of the following sort: ‘X committed the murder(s) for reason Y. Ah, but why did X have reason Y as a motivation? Because of reason Z.’

I am being deliberately cryptic because I don’t want to give away any of the wonderful surprises this book contains. All I really want to say is read it! Read it now!

Chapter 1

Old Lanscombe moved totteringly from room to room, pulling up the blinds. Now and then he peered with screwed up rheumy eyes through the windows.

Soon they would be coming back from the funeral. He shuffled along a little faster. There were so many windows.

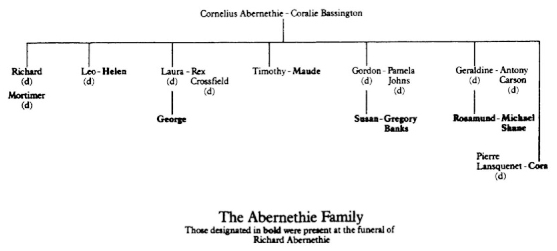

Enderby Hall was a vast Victorian house built in the Gothic style. In every room the curtains were of rich faded brocade or velvet. Some of the walls were still hung with faded silk. In the green drawing-room, the old butler glanced up at the portrait above the mantel-piece of old Cornelius Abernethie for whom Enderby Hall had been built. Cornelius Abernethie’s brown beard stuck forward aggressively, his hand rested on a terrestrial globe, whether by desire of the sitter, or as a symbolic conceit on the part of the artist, no one could tell.

A very forceful looking gentleman, so old Lanscombe had always thought, and was glad that he himself had never known him personally. Mr Richard had been his gentleman. A good master, Mr Richard. And taken very sudden, he’d been, though of course the doctor had been attending him for some little time. Ah, but the master had never recovered from the shock of young Mr Mortimer’s death. The old man shook his head as he hurried through a connecting door into the White Boudoir. Terrible, that had been, a real catastrophe. Such a fine upstanding young gentleman, so strong and healthy. You’d never have thought such a thing likely to happen to him. Pitiful, it had been, quite pitiful. And Mr Gordon killed in the war. One thing on top of another. That was the way things went nowadays. Too much for the master, it had been. And yet he’d seemed almost himself a week ago.

The third blind in the White Boudoir refused to go up as it should. It went up a little way and stuck. The springs were weak – that’s what it was – very old, these blinds were, like everything else in the house. And you couldn’t get these old things mended nowadays. Too old-fashioned, that’s what they’d say, shaking their heads in that silly superior way – as if the old things weren’t a great deal better than the new ones! He could tell them that! Gimcrack, half the new stuff was – came to pieces in your hands. The material wasn’t good, or the craftsmanship either. Oh yes, he could tell them.

Couldn’t do anything about this blind unless he got the steps. He didn’t like climbing up the steps much, these days, made him come over giddy. Anyway, he’d leave the blind for now. It didn’t matter, since the White Boudoir didn’t face the front of the house where it would be seen as the cars came back from the funeral – and it wasn’t as though the room was ever used nowadays. It was a lady’s room, this, and there hadn’t been a lady at Enderby for a long time now. A pity Mr Mortimer hadn’t married. Always going off to Norway for fishing and to Scotland for shooting and to Switzerland for those winter sports, instead of marrying some nice young lady and settling down at home with children running about the house. It was a long time since there had been any children in the house.

And Lanscombe’s mind went ranging back to a time that stood out clearly and distinctly – much more distinctly than the last twenty years or so, which were all blurred and confused and he couldn’t really remember who had come and gone or indeed what they looked like. But he could remember the old days well enough.

More like a father to those young brothers and sisters of his, Mr Richard had been. Twenty-four when his father had died, and he’d pitched in right away to the business, going off every day as punctual as clockwork, and keeping the house running and everything as lavish as it could be. A very happy household with all those young ladies and gentlemen growing up. Fights and quarrels now and again, of course, and those governesses had had a bad time of it! Poor-spirited creatures, governesses, Lanscombe had always despised them. Very spirited the young ladies had been. Miss Geraldine in particular. Miss Cora, too, although she was so much younger. And now Mr Leo was dead, and Miss Laura gone too. And Mr Timothy such a sad invalid. And Miss Geraldine dying somewhere abroad. And Mr Gordon killed in the war. Although he was the eldest, Mr Richard himself turned out the strongest of the lot. Outlived them all, he had – at least not quite because Mr Timothy was still alive and little Miss Cora who’d married that unpleasant artist chap. Twenty-five years since he’d seen her and she’d been a pretty young girl when she went off with that chap, and now he’d hardly have known her, grown so stout – and so arty-crafty in her dress! A Frenchman her husband had been, or nearly a Frenchman – and no good ever came of marrying one of them! But Miss Cora had always been a bit – well simple like you’d call it if she’d lived in a village. Always one of them in a family.

She’d remembered him all right. ‘Why, it’s Lanscombe!’ she’d said and seemed ever so pleased to see him. Ah, they’d all been fond of him in the old days and when there was a dinner party they’d crept down to the pantry and he’d given them jelly and Charlotte Russe when it came out of the dining-room. They’d all known old Lanscombe, and now there was hardly anyone who remembered. Just the younger lot whom he could never keep clear in his mind and who just thought of him as a butler who’d been there a long time. A lot of strangers, he had thought, when they all arrived for the funeral – and a seedy lot of strangers at that!

Not Mrs Leo – she was different. She and Mr Leo had come here off and on ever since Mr Leo married. She was a nice lady, Mrs Leo – a real lady. Wore proper clothes and did her hair well and looked what she was. And the master had always been fond of her. A pity that she and Mr Leo had never had any children . . .

Lanscombe roused himself; what was he doing standing here and dreaming about old days with so much to be done? The blinds were all attended to on the ground floor now, and he’d told Janet to go upstairs and do the bedrooms. He and Janet and the cook had gone to the funeral service in the church but instead of going on to the Crematorium they’d driven back to the house to get the blinds up and the lunch ready. Cold lunch, of course, it had to be. Ham and chicken and tongue and salad. With cold lemon soufflé and apple tart to follow. Hot soup first – and he’d better go along and see that Marjorie had got it on ready to serve, for they’d be back in a minute or two now for certain.

Lanscombe broke into a shuffling trot across the room. His gaze, abstracted and uncurious, just swept up to the picture over this mantelpiece – the companion portrait to the one in the green drawing-room. It was a nice painting of white satin and pearls. The human being round whom they were draped and clasped was not nearly so impressive. Meek features, a rosebud mouth, hair parted in the middle. A woman both modest and unassuming. The only thing really worthy of note about Mrs Cornelius Abernethie had been her name – Coralie.

For over sixty years after their original appearance, Coral Cornplasters and the allied ‘Coral’ foot preparations still held their own. Whether there had ever been anything outstanding about Coral Cornplasters nobody could say – but they had appealed to the public fancy. On a foundation of Coral Cornplasters there had arisen this neo-Gothic palace, its acres of gardens, and the money that had paid out an income to seven sons and daughters and had allowed Richard Abernethie to die three days ago a very rich man.

II

Looking into the kitchen with a word of admonition, Lanscombe was snapped at by Marjorie, the cook. Marjorie was young, only twenty-seven, and was a constant irritation to Lanscombe as being so far removed from what his conception of a proper cook should be. She had no dignity and no proper appreciation of his, Lanscombe’s, position. She frequently called the house ‘a proper old mausoleum’ and complained of the immense area of the kitchen, scullery and larder, saying that it was a ‘day’s walk to get round them all’. She had been at Enderby two years and only stayed because in the first place the money was good, and in the second because Mr Abernethie had really appreciated her cooking. She cooked very well. Janet, who stood by the kitchen table, refreshing herself with a cup of tea, was an elderly house-maid who, although enjoying frequent acid disputes with Lanscombe, was nevertheless usually in alliance with him against the younger generation as represented by Marjorie. The fourth person in the kitchen was Mrs Jacks, who ‘came in’ to lend assistance where it was wanted and who had much enjoyed the funeral.

‘Beautiful it was,’ she said with a decorous sniff as she replenished her cup. ‘Nineteen cars and the church quite full and the Canon read the service beautiful, I thought. A nice fine day for it, too. Ah, poor dear Mr Abernethie, there’s not many like him left in the world. Respected by all, he was.’

There was the note of a horn and the sound of a car coming up the drive, and Mrs Jacks put down her cup and exclaimed: ‘Here they are.’

Marjorie turned up the gas under her large saucepan of creamy chicken soup. The large kitchen range of the days of Victorian grandeur stood cold and unused, like an altar to the past.

The cars drove up one after the other and the people issuing from them in their black clothes moved rather uncertainly across the hall and into the big green drawing-room. In the big steel grate a fire was burning, tribute to the first chill of the autumn days and calculated to counteract the further chill of standing about at a funeral.

Lanscombe entered the room, offering glasses of sherry on a silver tray.

Mr Entwhistle, senior partner of the old and respected firm of Bollard, Entwhistle, Entwhistle and Bollard, stood with his back to the fireplace warming himself. He accepted a glass of sherry, and surveyed the company with his shrewd lawyer’s gaze. Not all of them were personally known to him, and he was under the necessity of sorting them out, so to speak. Introductions before the departure for the funeral had been hushed and perfunctory.

Appraising old Lanscombe first, Mr Entwhistle thought to himself, ‘Getting very shaky, poor old chap – going on for ninety I shouldn’t wonder. Well, he’ll have that nice little annuity. Nothing for him to worry about. Faithful soul. No such thing as old-fashioned service nowadays. Household helps and baby sitters, God help us all! A sad world. Just as well, perhaps, poor Richard didn’t last his full time. He hadn’t much to live for.’

To Mr Entwhistle, who was seventy-two, Richard Abernethie’s death at sixty-eight was definitely that of a man dead before his time. Mr Entwhistle had retired from active business two years ago, but as executor of Richard Abernethie’s will and in respect of one of his oldest clients who was also a personal friend, he had made the journey to the North.

Reflecting in his own mind on the provisions of the will, he mentally appraised the family.

Mrs Leo, Helen, he knew well, of course. A very charming woman for whom he had both liking and respect. His eyes dwelt approvingly on her now as she stood near one of the windows. Black suited her. She had kept her figure well. He liked the clear cut features, the springing line of grey hair back from her temples and the eyes that had once been likened to cornflowers and which were still quite vividly blue.

How old was Helen now? About fifty-one or -two, he supposed. Strange that she had never married again after Leo’s death. An attractive woman. Ah, but they had been very devoted, those two.

His eyes went on to Mrs Timothy. He had never known her very well. Black didn’t suit her – country tweeds were her wear. A big sensible capable-looking woman. She’d always been a good devoted wife to Timothy. Looking after his health, fussing over him – fussing over him a bit too much, probably. Was there really anything the matter with Timothy? Just a hypochondriac, Mr Entwhistle suspected. Richard Abernethie had suspected so, too. ‘Weak chest, of course, when he was a boy,’ he had said. ‘But blest if I think there’s much wrong with him now.’ Oh well, everybody had to have some hobby. Timothy’s hobby was the all absorbing one of his own health. Was Mrs Tim taken in? Probably not – but women never admitted that sort of thing. Timothy must be quite comfortably off. He’d never been a spendthrift. However, the extra would not come amiss – not in these days of taxation. He’d probably had to retrench his scale of living a good deal since the war.

Mr Entwhistle transferred his attention to George Crossfield, Laura’s son. Dubious sort of fellow Laura had married. Nobody had ever known much about him. A stockbroker he had called himself. Young George was in a solicitor’s office – not a very reputable firm. Good-looking young fellow – but something a little shifty about him. He couldn’t have too much to live on. Laura had been a complete fool over her investments. She’d left next to nothing when she died five years ago. A handsome romantic girl she’d been, but no money sense.

Mr Entwhistle’s eyes went on from George Crossfield. Which of the two girls was which? Ah yes, that was Rosamund, Geraldine’s daughter, looking at the wax flowers on the malachite table. Pretty girl, beautiful, in fact – rather a silly face. On the stage. Repertory companies or some nonsense like that. Had married an actor, too. Good-looking fellow. ‘And knows he is,’ thought Mr Entwhistle, who was prejudiced against the stage as a profession. ‘Wonder what sort of a background he has and where he comes from.’

He looked disapprovingly at Michael Shane with his fair hair and his haggard charm.

Now Susan, Gordon’s daughter, would do much better on the stage than Rosamund. More personality. A little too much personality for everyday life, perhaps. She was quite near him and Mr Entwhistle studied her covertly. Dark hair, hazel – almost golden – eyes, a sulky attractive mouth. Beside her was the husband she had just married – a chemist’s assistant, he understood. Really, a chemist’s assistant! In Mr Entwhistle’s creed girls did not marry young men who served behind a counter. But now of course, they married anybody!The young man, who had a pale nondescript face and sandy hair, seemed very ill at ease. Mr Entwhistle wondered why, but decided charitably that it was the strain of meeting so many of his wife’s relations.