Полная версия

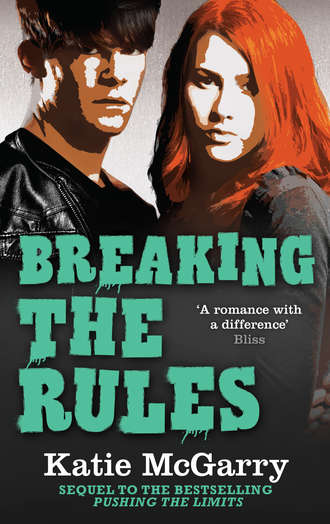

Breaking The Rules

“We’re okay,” I lie. It feels like it did when they lowered my parents’ caskets into the ground. It feels like it did when Echo broke up with me a few months back. It feels like it did when I decided that my brothers were better off without me.

Echo slides an arm around my chest and holds on like I’m preventing her from falling off a cliff. My girl sometimes mentions God. Some days she believes in him. Other days she’s not sure he exists. I don’t think much one way or another because if there is one, he doesn’t believe in me.

With that said, I toss up a silent prayer that all this hurt, all this guilt, will be gone in the morning. Not for my sake, but for Echo’s.

She deserves happiness.

Echo

“I’m two hours late calling my father, my boyfriend looks like he’s ready to step in front of an oncoming freight train to cure his boredom, I’m terrified someone will mention my mother and no, I don’t like the use of the gold against the greens in the painting.”

It’s how I’d love to respond to the curator tipping her empty champagne glass at the floor-to-ceiling painting in front of us, but admitting such things will hurt the fragile reputation I’ve established for myself this summer in the art community. Instead, I blink three times and say, “It’s beautiful.”

I glance over at Noah to see if he caught my tell of lying. He bet me that I couldn’t keep from either lying or blinking if I did lie for the entire night. Thankfully, he’s absorbed in a six foot carving of an upright prairie dog that has headphones stuck to his ears. If I lose, I’ll be listening to his music for the entire car ride home from Colorado. There’s only so much heavy metal a girl can take before sticking nails into her ears.

In a white button-down shirt with the sleeves rolled up, jeans and black combat boots, Noah shakes his head to himself before downing the champagne in his hand. Absorbed was an overstatement. Prisoners being water tortured are possibly having a better time.

Noah stops the waiter with a glare and switches his empty glass for a full one. He’s been scaring the crap out of this guy all night and at this rate, Noah may get us both kicked out, which may not be bad.

“I heard you tried to secure an appointment with Clayton Teal so he could see your paintings.” The curator’s hair is black, just like I imagine her soul must be, yet I force the fake grin higher on my face.

“I did.” And he rejected me, or rather the assistant to his assistant rejected me. I can’t sneeze this summer without someone gossiping about it. I swear this is worse than high school. It’s been months since graduating from what I thought was the worst place on earth, and I’ve descended into a new type of hell.

“Little lofty, don’t you believe?”

“I sold several paintings this spring and—”

She actually tsks me. Tsks. Who does that? “And you don’t think your mother had anything to do with those sales?”

My head flinches back like I’ve been slapped, and the wicked witch across from me sips her champagne in a poor attempt to mask her glee.

“Well?” she prods.

I tuck my red curls behind my ear. “My work speaks for itself.”

“I’m sure it does.” She gives me the judgmental once-over, and her eyes linger on the scars on my forearms. The black sleeveless dress shrinks against my skin. I’ve only had the courage to show my arms since last April, and sometimes, as in now, that courage dwindles.

In high school, no one knew how the white, red and raised marks had come to be on my arms, and for a long period of time, neither did I. My mind repressed the night of the accident between me and my mother. But with the help of my therapist, Mrs. Collins, I remember that night.

As I’ve traveled west this summer, visiting art galleries, I’ve discovered a few people in my mother’s circle are aware of how I had fallen through her stained-glass window when I had tried to prevent her from committing suicide.

Unfortunately, I’ve also met a few people who loathe my mother and prefer to slather their displeasure with her like a poisoned moisturizer onto my face.

“She contacted people, you know?” she says. “Telling them that you were traveling this summer like a poor peddler and that she’d be grateful if they showed you some support.”

It appears this woman belongs to the I-hate-your-mother camp, and the sole reason I’ve been asked to this art showing is for retribution for some unknown crime committed by my mother. A person, by the way, I no longer have contact with. “Would you have been one of those people she called?”

She smiles in the I-drown-kittens-for-fun sort of way. “Your mother knows better than to call me.”

“That’s nice to know.” I half hope my mother dropped a house on her sister and that she’s next.

The curator angles away from me as if our conversation is already done, yet she continues to speak. “A piece of advice, if I may?”

If it’ll encourage her to pour water over herself so that she’ll melt, I’m all for advice. “Sure.”

“There’s no skipping ahead. Everyone has to pay their dues and you, my dear, the daughter of the great Cassie Emerson, are no exception. Using your mother’s name, no matter how many people are misguided into believing her work is brilliant, is no substitute for actual talent. I’m taking this meeting with you tomorrow because I promised a friend of mine from Missouri that I would if he agreed to feature some of my paintings. Do us both a favor and don’t show.”

I know the man she refers to. He was one of the last to buy a painting from me and since that day in June, I’ve hit a dry spell. The smile I’ve faked most of the night finally wanes, and Noah notices as he sets his glass on the outstretched prairie dog’s hand.

I had two goals for this summer. Number one: to explore my relationship with Noah, and that has proven more complicated than I would have ever imagined. Number two was to affirm to myself and the art world that I’m a force of nature—someone separate from my mother. Regardless of what my father believes, that I’m capable of making a living with canvas and paint and that I have enough talent to survive in an unforgiving world.

The curator turns to walk away, but my question stops her. “If you detest me so much, then why invite me tonight?”

“Because,” she says, and her eyes flicker to my scars again. “I wanted to see for myself if the rumors were true. If Cassie really did try to kill her daughter.”

Wetness stings my eyes, and I stiffen. I wish for Noah’s indifferent attitude or one of his non-blood sister Beth’s witty comebacks. Instead, I have nothing, but this witch didn’t completely break me. She was the first to look away then leave.

The corners of my mouth tremble as I attempt to smile. Realizing that faking happiness is completely out of the realm of reality, I let the frown win. But I’ll go to hell before I cry in front of this woman. I release a shaky breath and will the tears away.

A waiter passes and in one smooth motion I grab a glass of champagne off his tray and hurry for the door. My heart picks up pace, and my throat constricts. This isn’t how the summer was supposed to go. I was supposed to evolve into someone else...someone better.

I slide past a couple gesturing at a painting, and the glass nearly slips from my hand when I ram into a wall of solid flesh. “What’s going on, Echo?”

“Nothing.” Something. Everything. I pivot away from Noah, not wanting him to see how each seam of my fragile sanity is unraveling one excruciating thread at a time in rapid succession.

Noah’s hand cups my waist, and his chest heats my back as he steps into me. “Doesn’t look like nothing.”

I briefly close my eyes when his warm breath fans over my neck, and his voice purrs against my skin. It’s a pleasing tickle. Peace in the middle of torture.

“Look at me, baby.” When I look up, Noah’s beside me, and his chocolate-brown eyes search mine. “Tell me what you need.”

“To get out of here.” The words are so honest that they rub my soul raw.

Noah places a hand on the small of my back and in seconds we’re out the front door and into the damp night. Drops of water cling to the branches and leaves of the trees. Moisture hangs in the air. Each intake of oxygen is full of the scent of wet grass. While inside experiencing my own hurricane, it rained outside.

She contacted people, you know? I didn’t know. I had no idea, and the thought that any of my success belongs to Mom kills me. A literal stabbing of my heart, shredding it to pieces.

Resting the champagne glass I’ve now stolen onto the hood of the car, I tear into the small purse dangling from my wrist and power on my phone. The same words greet me: one new message.

Not listening to my father or Noah or anyone, I kept it. Last April, I thought I could sever my mother from my life—that after one meeting with her, I could move on, but she’s still here, surrounding me, haunting me, like shrapnel embedded too deep to retrieve.

Noah slowly rounds on me as if I’m teetering on the edge of a bridge, ready to jump. As I meet his eyes, I realize he’s not far off. “She called people. She told them to buy my stuff.”

He assesses the phone then refocuses on me. “Your mom?”

I nod.

“Who’d she call?”

“The galleries...” I trail off when the door to the gallery opens and laughter drifts into the night. My mind jumps around, searching for another answer, hoping for a plausible solution other than that I’ve been handed the truth.

But maybe Mom didn’t call. Maybe this woman is wrong. Maybe the curator is mean and she’s evil and before I can think it through, my thumb is over the button. The phone springs to life. Numbers dial. Little lines grow with the cell phone reception. The phone rings loudly once.

Noah bolts forward. “What the fuck do you—”

“Echo?” The desperate sound of my mother’s voice shatters past the confusion and slams the fear of God into my veins. The phone tumbles from my hands and crashes to the ground.

The phone beeps—the call lost—and Noah stands openmouthed over the cell as if I murdered someone. “What the hell, Echo?”

“I...” The rest of my statement, my train of thought, catches in my throat. I called her. I knot my fingers into my hair and pull, creating pain. Oh, my God, I called her. I initiated contact, and now the door is open...

Cotton-mouthed, I whisper, “What have I done?”

Noah scrubs both of his hands over his face. “I don’t know.”

“This is bad.”

He steps forward. “It’s not. You hung up. She’ll assume it was a mistake.”

The phone rings. Each shrill into the night is like a knife slicing through me, and the panic building in my chest becomes this pressure that’s difficult to contain—a pulse that’s hard to resist. Answer, answer, answer!

“Think about this, Echo.”

My eyes snap to Noah’s. “I need to know.”

“She’s not going to give you the answers you want.”

“What if she did call the galleries? What if my success was a pity offering from her?”

“Echo—”

Closer than him, more desperate than him, I swipe the phone off the ground before he can move, but the phone stops ringing. My hands shake, and this desperation claws at me as I run a hand over my neck, searching for whatever is constricting my ability to breathe. “I could call her back.”

With both hands in the air like he’s handling a kidnapping negotiation, Noah edges in my direction. “You could, but let’s discuss it first.”

My fingers clutch the phone. “If she did this I need to know. I need to know if she asked people to buy those paintings from me.”

“What if she did? Why does it matter?”

“Because if she did, I’m a failure!”

He halts, and his eyebrows furrow together. “That’s bullshit.”

“But it’s true.”

“It’s not. Nothing good happens when you talk to your mom. What makes this different? What she says to you, what she’s done—it fucks with you!”

“She’s my mom!”

“And I’m the one holding you in the middle of the night when you can’t decipher what’s real and what’s a dream. She’s not here. I am. Not her!”

Anger explodes up from my toes and spirals out of my body. “You don’t understand! It’s more than the paintings. It’s more! She’s my mom. You don’t understand what it’s like to be torn between wanting to hate someone and wanting them in your life, then hating them all over again!”

“Fuck that, because I do. My mom’s family contacted me. They want to meet me. The goddamned people she ran from want me in their fucked-up lives.”

Noah

Echo and I stare at each other, and I suck in air to get my breathing under control. Her eyes are too wide, and my heart’s pounding too fast. It’s not how I meant to tell her, but it’s out, and I can’t take it back. The edges of my sight are blurry. I’ve drunk too much, but I’m glad the truth is out.

“What did you say?” she asks.

I yank the folded email out of my back pocket and offer it to her. Echo reaches for the paper like she’s seconds from handling a ticking time bomb. She unfolds it, and I slump against her car. Rainwater pooled on the hood, and it soaks through the bottom of my jeans. Damn this entire week to hell.

Too many emotions collide in my brain, and I rake both hands through my hair to ward off any spinning. The alcohol was supposed to help, not hurt.

“It’s not that long, so quit stalling.” The email is short, to the point, and every misspelling informs me that the shit I’m in is deep.

Ms. Peterson,

We no the adoption is compleet, but we’d like to see the boys for a visit. My Sarah wood have wanted that. If not the younger ones, then Noah. He’d be a teen by now. Let him decide.

Diana Perry

The paper crackles as Echo folds it again, and her heels click against the blacktop. Her sweet scent surrounds me followed by the butterfly touch of her fingers on my wrist. “Noah.”

She lowers her hand to my thigh and damn if fire doesn’t lick up my leg. Even when I’m drunk, my body responds to her. My legs automatically drop open, and the tension melts as she eases herself closer. Her fingers caress my face and with gentle pressure, she edges my chin up. I lose myself in those green eyes.

“What are you going to do?” she asks.

I wind my arms around her waist and slide one hand down her spine. Echo’s my solid, my base, my foundation. She has no idea that the single fear that keeps me up at night is knowing one day she’ll discover she doesn’t need me like I need her.

“Noah,” she whispers again. Echo’s always been a siren, calling me to her even when I don’t want to be captured. “Please talk to me.”

Her lips brush the corner of my mouth, and my fingers fist into her hair. Echo’s warm and soft. I shouldn’t kiss her now. I shouldn’t crave to kiss her now, but damn, she owns me.

“Talk to me,” she murmurs. “I can’t help if you don’t talk to me.”

As she sweeps my hair away from my eyes, I hear myself say, “They’re in Vail.”

Her head nods against mine in understanding. “We’ve got time before we have to be back.”

“Mom ran from them.”

“You don’t know that.” She pulls back to look at me, but my grip on her hips keeps her near. “There could be a million reasons why your mom left.”

“Carrie and Joe said that Mom’s family is bad news.”

“Carrie and Joe said that you shouldn’t have been around your brothers. They were wrong then. They can be wrong now.”

The same thought has circled in my brain since Carrie broke the news. “What if they’re right?”

“What if they’re wrong? And if they are right, what if your mom’s family did screw up? Maybe they deserve a second chance.”

My eyes flash to hers, and my blood goes ice-cold. “Are we talking about my situation or yours?”

She tilts her head. “They may not be so different.”

“Fuck that. There’s no comparison.”

“You’re drunk, Noah.”

“I am.”

Her foot taps against the ground, and she does that thing where she glares off in the distance. It’s not hard to read she’s silently tearing me a new ass, but has enough grace to leave the internals internal. One of these days, she’ll snap.

She’s torn into me before, and the last time she did, she left me. My stomach plummets as I wonder if she’ll walk again.

Reaching behind me, Echo lifts the glass of champagne she brought with her from the gallery. “Well, there’s good news. It looks like we’ll be free tomorrow. The curator and I decided it would be best if we no longer share breathing space...or continents.”

Echo presses the glass to her lips, but I lift it from her hand. I’ve had a few of those tonight. More than a few. Enough that walking a straight line could be a problem.

My girl throws me a hardened expression that could send me six feet deep. “Damn, Echo. I’m not stealing your firstborn. I’m the drunk one, remember?”

She releases a sigh that steals the oxygen from my lungs, and she moves so that her back rests against me. I mold myself around her and nuzzle my nose in her hair. Echo inclines her head to the glass now in my possession. “How many of those have you had?”

* * *

I drink half the champagne while eyeing the prairie dog again through the gallery window. Champagne’s not my style, but free alcohol is free alcohol. “Not enough to understand that.”

“It’s a prairie dog,” she answers.

“With headphones.”

“It’s a commentary on how we are destroying nature.”

“That’s wood, right?” I ask.

Echo rolls her eyes, and I smirk. She hates it when I do this.

“Yes, the artist cut down a tree, used a chainsaw that required gas, and the whole process defeats the purpose.”

“Chainsaw?” These bastards are strange.

“Yes.”

I finish out the glass. “As I said, not enough.”

A couple exits the gallery, and they’re way too loud and way too full of themselves to peer in our direction. While I could give a shit about everyone inside, Echo cares, and the longing in her eyes as she watches them hurts me.

“Want to talk about the stuck-up bitch in there?” I ask.

“Nope.”

Good. Odds are I’d say things that would make Echo cry. “Then let’s get the fuck out of here.”

Echo

Noah and I slept deeply, we slept long, and then we held each other for longer than we should have. Now, checkout is looming.

Cross-legged on the middle of the bed, I cradle my cell and stare at three messages: one new voice mail, one missed call, one new text. Each one from my mom. There’s a pressure inside me—this overwhelming craving to please my mother, to gain her approval—that prevents me from deleting them. The memories don’t help...both the good and the bad.

Mom said she’s on her meds. She said that she’s in control of her life. If that’s true, is she mimicking my father’s parenting style by attempting to dominate my life?

Noah steps out of the bathroom fully dressed, and his hair, still wet from his earlier shower, hangs over his eyes, leaving me unable to read his mood.

“Did you call her?” he asks.

“No.” I pause. “But what if I did?”

Noah shrugs then leans his back against the wall. “Then you did. I don’t claim to understand, but I promised you back in the spring that I’d stand by you. I’m a man of my word.”

He is. He always has been. “But you don’t agree that I should call her.”

“Not my decision to make.”

I shift, uncomfortable that Noah’s not completely on my side. “I’d like to know you support me.”

“I support you.”

“But you don’t approve.”

“You need to stop looking for people’s approval, Echo. That’s only going to lead to hurt.”

My spine straightens. “I didn’t ask for a lecture.”

“You asked me to be okay with you contacting the person that tried to kill you. Forgive me for not setting off fireworks. You want to call her, call her. You want to see her, then do it. I’ll hold your hand every step of the way, but I don’t have to like seeing her in your life.”

His words sting, but they’re honest. The phone slides in my clammy hands. “I won’t call her today.”

“Because that’s your decision,” Noah says. “Not because you’re trying to please me.”

We’re silent for a bit before he continues, “I called the Malt and Burger in Vail. They can fit me into the schedule this week. If I want in, they can give me the walk-through of the restaurant this evening.”

A sickening ache causes me to drop a hand to my stomach. A week. We were supposed to travel back to Kentucky today. We were going to take another route so that I could try new galleries. But Noah has this need to find his mom’s family. He desires a place to belong.

Just like me.

If he wants to search for them, I can’t be the person standing in the way. “You should ask them to schedule you.”

“What if my mom’s family is bad news? Why would I want them in my life?”

“I don’t know.” It’s a great question. One I deal with daily. Maybe if we go, Noah will finally understand my struggle with my mother. “Let’s do this. Let’s go to Vail.”

Noah cuts his gaze from the floor to me. “This means you’ll be giving up visiting galleries on the way back.”

It will. Granting him this can cost me my dreams, but I’ve had enough time, and I guess I’ve failed. “There are probably galleries in Vail.” Hopefully.

“We’ll stay in a hotel the whole time. I’ll pay.”

“Noah...” My voice cracks. “No. I’m fine with the tent or I can help pay—”

“Let me do this,” he says, and the sadness in his tone causes me to nod.

“So we’re still heading west,” I say.

“West,” he responds.

Noah

My head pulses with the same speed as the cursor on the computer at the Vail Malt and Burger. Champagne hangovers suck.

“Clock in as soon as you walk in, and clock out the moment your shift is done and this is where you put your orders, you hear me?” The manager of the Malt and Burger is in the process of explaining to me the way “his” restaurant runs. He’s a six-two, two-hundred-and fifty-pound black man who, like the other managers throughout the summer, thinks he’s the only one that uses the system of sticking the paper orders over the grill. Two words: corporate policy.

“Got it,” I answer.

“You hear me?” he asks with a wide white grin. “It doesn’t leave the grill until it hits one hundred and sixty degrees.”

“Yeah, I hear you.” Food poisoning’s a bitch.

He slaps my back and if I wasn’t solid, the hit might have crushed me. “Good. Called around about you. Hear you’re a good man. We get a lot of travel employees through here, and you aren’t the only fresh face working this week. I expect you to pull your weight and not miss a beat, hear me? Otherwise, I’ll put you out.”

Loud and clear, and it’s going to be a long week if he says that phrase as much as he has in the past thirty minutes.

“So we’ll see you tomorrow?” He uses a red bandanna to wipe the sweat off his brow.

“Tomorrow.”

We shake hands, and I let myself out the back when the drive-through worker yells that the headset shorted. Vail’s cooler than Denver, but not by much and because of that, I walk in the shadows of the alley.

“You were too serious-looking in there, you know? Surely a year can’t change someone that much.”

I glance behind me and notice a girl with short black hair and wearing a Malt and Burger waitress T-shirt leaning against the brick wall next to the Dumpster. A cigarette dangles from her hand and as she lifts it to her mouth, the ton of bracelets on her wrist clanks together.

“Do you know me?” I ask.

She releases smoke into the air. The sweet scent catches up and for the first time in months, the impulse for a hit becomes an itch under my skin. The chick’s smoking pot.

“I know you, Noah Hutchins. I know you very well.”