Полная версия

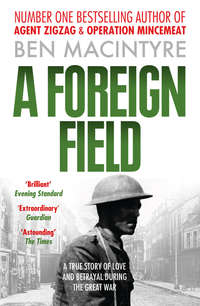

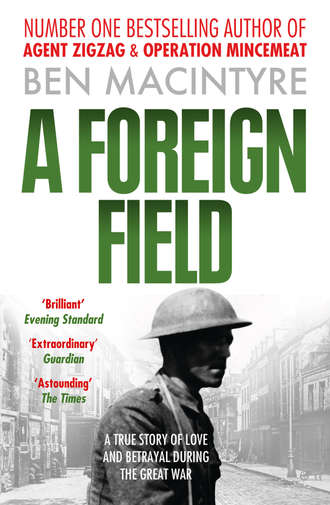

A Foreign Field

Where shall the traitor rest,

He, the deceiver,

Who could win maiden’s breast,

Ruin, and leave her?

In the lost battle,

Borne down by the flying,

Where mingles war’s rattle

With groans of the dying.

And when the mountain sound I heard

Which bids us be for storm prepar’d

The distant rustling of his wings,

As up his force the tempest brings.

At nine in the morning, the attack finally began, and the officers of the Hampshire Regiment had ‘the pleasure of seeing Germans coming forward in large masses’. Under cover, a handful of Gennans crept up to the Hampshires’ position and shouted ‘Retreat!’, in English. It all still seemed to be a public school game. British snipers tried to pick off the machine-gun crews and officers, distinguishable by their swords. Heavy fire was exchanged and then, inexplicably, the guns on both sides fell quiet. ‘The stillness was remarkable; even the birds were silent, as if overawed.’ Just as suddenly, the battle resumed with deafening violence. Grey troops rushed across the clover, and it was ‘as if every gun and rifle in the German army had opened fire’. Too late, the order was given for the Hampshires to withdraw. Seizing rifle and pack, Private Digby joined the throng fleeing down narrow lanes. As dusk gathered, the chaos spread. ‘We marvellously escaped annihilation,’ Private Frank Pattenden wrote in his diary. ‘It was nearly wholesale rout and slaughter.’ Lurching south, the regiment began to dissolve, mixing with other fragments of the disintegrating rump of the British army. At nightfall, a small contingent of 300 Hampshires briefly held on in the village of Ligny, but then fell back once more, leaving behind dozens of injured men in a temporary dressing station. The walking wounded made their way into the woods, and the remainder waited in the darkness.

The Hampshires tramped on through the night across fields, snatching two hours’ sleep beneath a hedgerow. In the morning they stumbled into the village of Villers-Outréaux, where a German battery awaited them, having leap-frogged the retreating British in the dark. It opened up when the Hampshires were a hundred yards away. A force of fifty men under Colonel Jackson was left to provide cover, and fought dismounted German cavalry and cyclists with rifle and bayonet as the main body of troops scrambled away. Jackson was shot in the legs and carried into the home of the local curé, where he was captured a few hours later. Private Pattenden, struggling south on bleeding feet, noted the gaps in the ranks and the many missing men: ‘I am too full for words or speech and feel paralysed as this affair is now turning into a horrible slaughter … my God it is heart breaking … we have no good officers left, our NCOs are useless as women, our nerves are all shattered and we don’t know what the end will be. Death is on every side.’ The tall figure of Private Robert Digby was last seen by his comrades clutching a bloodied arm in the temporary dressing station in Ligny. A German bullet had passed through his left forearm, narrowly missing the bone, a debilitating ‘Blighty wound’ – the sort of injury that was survivable but deemed serious enough to warrant a passage home – that men would later long for in the trenches.

When Robert Digby re-emerged from the surgeon’s tent, his arm hastily bandaged and held in a rough sling, he was no longer part of a moving mass of men, but alone. ‘I lost my army,’ he would later observe ruefully. He had also lost his Lee Enfield rifle, his bayonet, 120 rounds of ammunition, his peaked cap, his knapsack, and his bearings.

Captain Williams, the surgeon of the Hampshire Regiment, was tending the wounded when the Germans stormed into Ligny. But by then Digby had taken solitary flight. A final, brief and unemotional entry in British military records concludes his official contribution to the Great War: ‘Private Robert Digby, Wounded: 26th August, 1914.’

The previous day, William Thorpe, a tubby and genial soldier of the King’s Own Lancaster Regiment, had been sitting down to breakfast in the corn stubble above Haucourt when his war started. Thorpe and the other men were tired, having marched for three days to meet the advancing German forces, but their spirits were high. ‘The weather was perfect,’ noted one of Willie’s officers, and even the spectacle of Belgian refugees fleeing south, as ‘dense as the crowd from a race meeting but absolutely silent’, had not much dampened the mood as the King’s Own marched from the railhead. The soldiers whooped at a reconnaissance plane flying overhead, which came under ragged fire from somewhere in the rear, although Captain Higgins declared the aircraft to be British.

Lieutenant Colonel Dykes had led the column of twenty-six officers and 974 other ranks past a tiny church north of Haucourt, down a gentle slope to a stream, and then up a steep hill to a plateau on the extreme right of the British line, before he gave the order to rest. ‘A full 7 to 10 minutes was spent admonishing the troops when it was found that some had piled their weapons out of alignment.’ The time might have been better spent looking at the horizon. An hour earlier the troops had been ‘greatly reassured’, although amazed, by the sight of a French cavalry unit, clad in their remarkable plumes, breastplates, and helmets: handsome and conspicuous imperial anachronisms. Since the French advance guard was supposed to be out ahead of the British troops, an officer declared that the enemy ‘could not possibly worry us for at least three hours’. This was, therefore, an excellent moment to eat breakfast.

As they waited for the mess cart to arrive, the officers observed another group of uniformed horsemen some 500 yards away, which paused to watch the relaxing troops before trotting away. One of the younger officers quietly suggested that the cavalrymen might not be French, and was sharply told ‘not to talk nonsense’. The men were lounging and talking in groups in the quiet cornfield; the sun was growing warm when the mess cart finally rumbled up. On top of the wagon perched the regimental mascot, a small white fox terrier, clad in a patriotic Union Jack coat, that had been adopted before leaving Southampton. ‘New life came to the men’, who leapt to their feet, mess tins at the ready.

At that moment the German Maxim guns opened up. Colonel Dykes was killed in the first burst, shot daintily through the eye, his groom making ‘a valiant attempt to hold his horse until it also was killed’. ‘Some tried to reach the valley behind,’ but the older and cannier soldiers lay flat on their faces and hugged the earth, as the bullets flicked the tops of the cut corn stalks. ‘Of those who got up, most were hit.’ After two minutes of uninterrupted firing, the German gunners paused to reload and the survivors scrambled for cover below the crest of the hill. For the next five hours, what remained of the regiment was pounded with shells. Through field glasses, the future Field Marshal Montgomery observed the ‘terrible sight’ and then followed orders to try to help the trapped Lancasters. ‘There was no reconnaissance, no plan, no covering fire. We rushed up the hill.’ With predictable results. This was ‘terrible work as we had to advance through a hail of bullets from rifles and machine guns and through a perfect storm of shrapnel fire. Our men … were knocked down like ninepins.’

Many of the wounded were too badly injured to be moved, and by late afternoon, when the order came to fall back, the King’s Own Lancasters had been torn apart. Haucourt church was packed with bleeding and dying men, while dazed pockets of survivors, separated in the panic, wandered in search of their commanding officers and orders. A day that had started in perfect calm ended in utter confusion, as what was left of the King’s Own joined the great retreat. ‘There was nothing to do for it but to leave the wounded and hope that any stragglers would rejoin,’ one officer said. When the battalion was finally able to draw breath, the losses seemed barely believable: fourteen officers and 431 other ranks killed, wounded or missing, along with the mess cart, commanding officer, two machine guns and the fox terrier. (The distraught driver of the mess wagon was found to be carrying the dead dog under his shirt the next day, and was sharply ordered to bury it.) In three hours of battle, the King’s Own Lancaster Regiment had lost half its strength and much of its morale. It had also lost Private William Thorpe.

David Martin, Thomas Donohoe and the Royal Irish Fusiliers had arrived in France in typically jovial fashion, ‘singing and cheering and chanting the regiment’s motto, Faugh-a-Ballagh, “Clear the Way”.’ The local French civilians found the Irishmen intriguingly odd, and the curiosity was mutual. During a reconnoitre to the east, one officer from the Irish regiment was taken prisoner by an over-enthusiastic French commander who evidently suspected that he had come across a German spy posing as an Allied soldier. He also seems to have had some peculiar notions about the distinguishing anatomical features of a British officer, for he told his astonished captive: ‘Although I am sure you are what you say you are, still these are unusual times and perhaps you would not mind undressing, and giving me some proof that you are English.’ The officer huffily refused to demonstrate his nationality thus, and sadly we will never know what the Frenchman hoped to find that would have convinced him.

Like the King’s Own Lancasters and the Hampshire Regiment, the Irish Fusiliers were positioned close to Haucourt, just south of the village. By mid-morning on 27 August, the regiment was locked in a ferocious artillery duel. ‘Outnumbered and outranged,’ the Irish troops fell back shortly before nightfall and by the early hours of the next day the battalion, one of the last regiments to vacate the position, was in headlong retreat, but still displaying a jollity that astonished the regimental interpreter: ‘I do not understand you Irish,’ he said. ‘We Frenchmen are glad when we go forward but sad when we come back; you Irish are always the same, you always laugh and all you want is bully beef.’

The laughter swiftly subsided as the withdrawal turned into a continuous forced march, often under attack from the rear. The day grew hot and humid, but there was no pause. Slogging along grimly ‘as if in a trance’, the men stripped off their packs and threw them by the roadside. As the twenty-fourth hour of non-stop marching approached, some were left ‘with only the remains of boots’. Others collapsed, ‘physically unable to march further without rest’, but there was no time to wait for them to recover, nor was there the means to move them. The brigade commander pressed on, noting that ‘to our rear the lurid glare of burning farms and haystacks shed a fitful light on the scene’. On the evening of 28 August the exhausted Irish troops crossed the Somme River, just before the bridge was blown up, and were able to rejoin the British rearguard. When the muster roll was called, 136 men and officers were found to be missing, including Privates Thomas Donohoe and David Martin.

CHAPTER TWO

Villeret, 1914

South of the cornfield battlefields lay Villeret, a small village of simple brick houses with roofs of slate, tile and thatch, tucked into the folds of the Picardy countryside. A wayfarer stumbling upon Villeret by chance in 1914 – and few strangers ever came through save by accident, since Villeret was not on the way to anywhere – might have paused to take in the picturesque view from the hill above the village, for as one traveller observed, ‘nature is beautiful around Villeret, and the poet or painter might stop here to depict the scene, one in the harmonious language of verse, the other by fixing the scene on his canvas’. The wanderer might also have stopped for a restorative drink, perhaps a glass of genièvre, the ferocious local gin, in the café on the corner: an establishment called ‘Aux Deux Entêtés’, the two hard-heads, with a sign showing two asses pulling stubbornly in opposite directions. Or he might have halted to observe the modest tombs in the undistinguished church, or to admire the well-kept rose garden in front of the girls’ school, the pride of the young schoolmistress, Antoinette Foulon. He might have inquired what great personage lived in the ornate, still-new château on the hill. But since he would most likely have been lost, he would have tarried just long enough to obtain directions before hurrying on to the larger settlement of Hargicourt, just across the valley, or to the ruined fortress at Le Câtelet, the most important town in the canton, five miles to the north on the road between Cambrai and Saint-Quentin.

Villeret moved to a rhythm and pattern as immutable and familiar as the motifs in the cloth woven down the centuries by its villagers. Here Léon Lelong baked his bread to a recipe bequeathed by the ancients; women in wooden clogs drew water from a pump in the cobbled square; and looms rattled in every cellar, reaching a crescendo at dusk and then slowly fading into the night, the steady clanking heartbeat of a Picardy village.

That August Villeret appeared, at least on its homely surface, to be following its regular ambling course, as contented as the pig lounging in the shade of butcher Cardon’s house. But a glance inside the door of the mairie, a grand two-storey structure with the unmistakable pomposity of French municipal architecture, might have offered a rather different impression. For in the summer of 1914 Villeret was on a war footing, its elders in a state of unprecedented anxiety. Of the approaching German army, and the carnage it had wrought, Villeret knew almost nothing. But the war had already jolted village life out of kilter, and Camille ‘Parfait’ Marié, the acting mayor of Villeret, was having to put his mind to a problem not encountered by the village since the Prussians had marched into northern France forty-four years previously: with so many men already summoned into uniform, there would be barely enough hands to bring in the harvest, which was late this year as it was. (At the same time, across the Channel, the conflict in Europe was impinging on normal existence in a similarly upsetting fashion. On 4 August, the Catford Journal reported: ‘What with the war and the rain, last Saturday was a most depressing day for the Catford Cricket Club.’)

War had officially begun in Villeret at exactly five o’clock on the afternoon of 1 August, when Le Câtelet’s garde champêtre, or municipal policeman, marched portentously up rue d’En-Bas, clanging his bell to announce mobilisation. Some of the boys had been so anxious to get into battle they had dropped their tools in the fields. Within a few hours of hasty farewells the village population of roughly 600 had shrunk by more than a third. Even the mayor, Edouard Severin, rushed off to war, leaving his deputy in charge. Thrust into a position of uninvited responsibility, Marié, a charcoal-maker with drooping moustaches, thick spectacles, and a permanently unhappy mien, quickly found the weight of office burdensome. The acting mayor was universally known as ‘Parfait’, which happened to be his middle name, but which also aptly reflected his cast of mind: he was a perfectionist, albeit a constantly frustrated one, and missives from the préfecture at Saint-Quentin had begun arriving on his desk in swift and baffling succession.

On 5 August the sous-préfet demanded: ‘How many workers are needed to bring in the harvest? Please reply as soon as possible and before midday tomorrow.’ Then someone calling himself the ‘President of the Food Commission’ wanted to know exactly how much wheat, dry and ground, was immediately available. Next, with powerful oddness, it was decreed that all street advertising for Bouillon Kub, a variety of powdered broth, should be torn down. German spies were suspected of leaving a trail of messages on such hoardings for the use of advancing troops, but since Marié could not possibly have known this, the request must have seemed, to say the least, eccentric.

A little over a week later another impossible order landed on Marie’s desk – ‘Extend help to all needy English, Belgian, Russian or Serb families.’

There were no such families in Villeret, for even by the standards of rural northern France the community was an isolated and self-contained one. Even the inhabitants of Hargicourt, just a quarter of a mile away, were considered ‘foreigners’ by the Villeret folk, and regarded with abiding distrust. In turn, the people of Villeret were often dismissed by neighbouring communities as a collection of ‘gypsies’, backward peasants who kept to themselves. There was a local saying: ‘The rich folk of Hargicourt, the clever folk of Nauroy and the savages of Villeret.’ Like that of many villages in Picardy, the social structure of Villeret was founded on an interrelated network of clans, families linked by blood, marriage and feuds. For as long as anyone could remember, Villeret had been home to the Mariés, the Cornailles, the Morelles, the Dessennes, the Foulons and the Lelongs – united by a common distrust of the world beyond the village boundary. Few Villeret villagers spent much time in Hargicourt or Le Câtelet, and only rarely would they travel the eight miles to the market town of Saint-Quentin, for the rest of France was a fickle place, important as a market for beet, wheat and brightly coloured cloth, but otherwise to be avoided. Villeret was not unique in this philosophy. One of the region’s historians described his fellow Picards as ‘frank and united, rarely keen to leave their land, living on little, sincere, loyal, free, brusque, attached to their opinions, firm in their resolution’. An old Picardy saying aptly captures the Villeret attitude, lying somewhere between selfishness and self-reliance: ‘Chacun s’n pen, chacun s’n erin’ (Chacun à son pain, chacun à son hareng), each has his own bread, each his own herring. In other words, mind your own business.

Many of Villeret’s inhabitants had multiple businesses: weaving, seasonal farming, occasional manual labour, perhaps a little tobacco-dealing or a café on the side. Alphonse Morelle, for example, called himself a weaver by trade, but explained: ‘Before the war I had a café and sold some tobacco, but in between times, at home, I did some weaving, and in the summer I hoed the beets and helped with the harvest.’

Some of the Villeret men worked in the Templeux-le-Guérard phosphate mine beyond Hargicourt, and although this brought in extra money, it coincidentally tended to compound the village reputation for anti-social behaviour. Inhaled phosphate dust had left many mine workers with damaged lungs, which were often treated only with copious quantities of blanche, a white liqueur similar to absinthe. The drink dulled the pain but, like absinthe, it also destroyed the mind, and there were at least forty people in Villeret with brain damage resulting from addiction to this poisonous brew. In 1914 the village contained no fewer than thirty ‘cafés’. Some of these were little more than cellars with a single barrel, while others were almost luxurious. The ‘Aux Deux Entêtés’ offered a billiards table, wind-up gramophone with a choice of sixty records, and an archery gallery, as well as a multitude of different drinks, from fine champagne to the throat-roasting genièvre.

Outsiders, particularly those with claims to cultural sophistication, were inclined to see the village as a rustic throwback. A new schoolteacher, Monsieur Duchange, had arrived in 1907 to find what he called a ‘thoroughly mediocre intellectual and moral standard’, a community populated by thieves and drunks, riven by internal bickering and run by a mayor who was corrupt, oppressive, and violent. Duchange left after three years, declaring he ‘would not want to stay a moment longer in such a place’. What the scandalised schoolteacher failed to appreciate was the other side of the Villeret character: a streak of hardy independence that could easily be taken for ignorant belligerence, unless it was on your side. Villeret was an easy place to miss, an easy place to disdain, but as the Kaiser was about to discover, it was not an easy place to subdue.

With the war approaching, the first wisps of fear, gossip, information and disinformation began to blow through the region, even reaching the isolated enclave of Villeret. Rumour insisted that German spies were in the area posing as Swiss mechanics repairing the looms. Two optimistic volunteers with a single gun and two cartridges set up a guard post on the road into Le Câtelet, and hung a chain across the road to hold back the German army. Some of the better-informed inhabitants made preparations to leave.

On 16 August, four days after the first troops of the British Expeditionary Force crossed the Channel, the locals had their first glimpse of an Englishman in uniform, in the form of an affable fellow on a motorcycle. With the schoolmistress of Le Câtelet translating, he managed to explain that he had been following an air squadron and was trying to get to Brussels. The villagers pointed to the north and before heading off the motorcyclist turned to survey the rolling fields as if he were a carefree tourist. His words were carefully recorded: ‘Oh, France, beautifully.’

German troops marched into Brussels four days later, but a week went by before another English soldier appeared in Villeret, this time demanding the whereabouts of the largest village shop. He was duly directed to the establishment of Alexis Morel, who was a part-time grocer, haberdasher, café-proprietor, liquor salesman, and sometime chairman of Villeret’s archery club. He also sold bread. The soldier instructed Morel to supply every loaf he had in stock to feed the advancing British army, and to prepare another batch for the following day. Morel complied without demur, but assiduously noted the cost of the requisitioned bread: ‘295 francs’.

It would be more than six years before Morel saw any reimbursement, and it swiftly became apparent that the British army, fuelled on his bread, was no longer advancing, but retreating. The first sign of the calamity was the sight of Belgian refugees, initially a trickle, but soon a torrent, moving south through Le Câtelet. ‘They had the unspeakable in their eyes; they carried their belongings and their gestures were despairing.’ The guns were now clearly audible.

Achille Poétte, the cadaverous, indefatigable postman of Villeret and chief local gossip, suddenly found himself unemployed when the postal service was abruptly terminated. That evening an exhausted squadron of French cavalrymen passed through Le Câtelet, their stumbling mounts, drawn faces, and evident lack of élan offering the first clear sign that victory had not materialised. The officer gamely insisted the retreat was merely strategic, a prelude to the flanking movement that would drive the Germans back. The people chose to believe him and when a passing refugee claimed that Walincourt, ten miles north, was already occupied, he was threatened with jail for spreading alarming news. But then came incontrovertible proof: long lines of horse-drawn ambulances carrying British wounded, and behind them columns of soldiers, their faces pallid from fatigue and fear. Ninety-five injured soldiers were treated at the makeshift hospital set up in Mademoiselle Founder d’Alincourt’s château at Le Câtelet, while the bakers’ ovens churned out extra loaves for the retreating men.

In her diary, the schoolteacher who had helped the lone English motorcyclist watched the British in retreat: ‘They had only one desire, to go faster, ever faster, to escape the enemy who, their desperate gestures seemed to say, was snapping at their heels.’ Cavalrymen rode slumped in their saddles, and infantrymen collapsed in Le Câtelet square and slept as they fell. Now the civilian exodus had begun. From Hargicourt some 300 people headed south, on foot or in wagons, and others began to seep out of Le Câtelet. ‘It is very sad to see the poor villagers flying south as we retire,’ wrote one British officer. ‘Those who, as we came north a fortnight ago, looked on us as their deliverers, are now thinking we are broken reeds. They are crying and asking us to save them and their homes … A ghastly business. Poor creatures.’