Полная версия

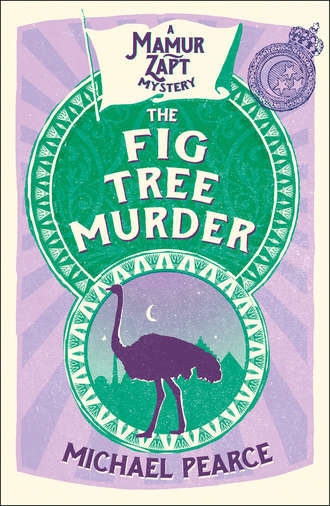

The Fig Tree Murder

‘I am sure I have no need to tell you, Captain Owen. But one thing I can say with confidence, that it certainly is not intended to be in the interests of the workers, neither the workers on the Heliopolis project nor workers in general in Egypt.’

‘Aren’t you making too much of this, Mr Rabbiki?’

The politician chuckled hoarsely.

‘I’m just making sure that you don’t make too little of it, Captain Owen. And in order to make quite sure, I shall put down a question in the Assembly from time to time. We shall all be following your progress with great interest, Captain Owen.’

McPhee stuck his head in at the door.

‘About the Tree, Owen—’

‘Look, thanks, I’ve got something else on my mind just at the moment.’

‘But it’s to do with the business at Matariya.’

McPhee came worriedly into the room.

‘Apparently, there’s been a development. There’s a rather difficult religious sheikh in the village, it seems—’

‘Yes. I’ve met him.’

‘Well, he’s bringing the Tree into it.’

‘He’s what?’

‘Bringing the Tree into it. It’s a Christian site, you see, of particular interest to Copts, but not just Copts, Catholics too. The balsam—’

‘What the hell’s the Tree got to do with it?’

‘Well, he says it’s not just an accident that the man was killed at that particular spot. It’s within the zone of influence of the Tree, and—’

‘So, it’s become an issue between Muslims and Christians?’ said Paul.

‘That’s right. As well.’

Paul took another drink. Then he put down his glass.

‘Political enough for you yet?’ he said maliciously.

‘First, I’m going to arrest the bloody Tree,’ said Owen.

When Owen got out of the train, the ordinary steam-train this time, at Matariya Station, he could see ahead of him the broad white track which led to Heliopolis. Away on the skyline were half-finished houses and men busy on a large construction of some sort: the new hotel, he supposed.

Nearer at hand, over to his right, a pair of humped oxen, blindfolded, were working a sagiya, or water-wheel. Its groan followed him as he walked.

Far to his left, above the mud parapet which hemmed in the waters of the Nile, he could see the tall sails of gyassas, like the wings of huge brown birds, gliding along the river. Closer to was the great white gash of the advancing end of the new railway. It was somewhere over there that he must have been two days before.

The track led through a vast field of young green wheat, away in the middle of which an ancient obelisk thrust upwards at the sky.

McPhee, he told himself, would have loved it: both the biblical landscape and the reminder of something even older, the original Heliopolis, City of the Sun, where Plato and Pythagoras had walked and talked, buried now, perhaps even beneath this very field of wheat.

McPhee was not the ordinary sort of policeman. His interests were in the Old Egypt rather than in the New; in the Egypt of the Pharaohs and the Ptolemies and Moses rather than in the Egypt of the Khedive and the occupying British and the foreign developers.

Owen’s mind, however, was gripped more by the New Egypt than by the Old. For he was the Mamur Zapt, Head of Cairo’s Secret Police, responsible for political order in the city, and the chief threat to that order came from the new forces that were emerging in the country, to do with nationalism, ethnic and religious tension, and the growing impatience with the traditional rule of the Pashas.

If it were not for the fact that the Old Egypt had a habit of rising up every so often and giving the New an almighty kick in the teeth!

2

The Tree was in a bad way. It lay prone on the ground and although it was green at the top it was very brown underneath. Its bark was gnarled and twisted and much gashed where the irreverent, or, possibly, the reverent, had carved their names.

‘That’s why I had to put a railing round it,’ explained the man who claimed to be its owner, a Copt named Daniel.

There was a wooden palisade all round the Tree. It, too, was covered with names.

‘It costs ten piastres to put your name on,’ said the Copt.

‘Ten piastres!’ said Owen, aghast.

‘That includes the hire of a knife,’ said the Copt defensively, brandishing a large blunt-edged instrument.

‘But ten piastres!’

‘Think, Effendi!’ said the Copt persuasively. ‘Your name bound to a holy relic for perpetuity! That will surely count for something on the Day of Judgement!’

‘You don’t think overcharging may also count for something on the Day of Judgement?’

‘The Tree has many virtues, Effendi,’ said the Copt, smiling.

‘Evidently. But does it not, from what I hear, have vices, too?’

‘That is a calumny put about by the Muslims.’

‘But is there not some truth in it? For I have heard a man lies dead because of the Tree.’

‘That is a story got up by Sheikh Isa. For his own ends.’

‘Ah?’

‘He wishes to drive me out. So that he can take over custodianship of the Tree himself.’

‘But why would he want to do that? If the Tree lacks virtue? And isn’t the Tree a Christian relic rather than a Muslim one?’

‘It is a Muslim one too. As for the virtue, that would return if the Tree were in proper hands. Muslim ones. They say.’

‘And what do you say?’

‘That Sheikh Isa is a greedy old bugger who just wants to get his hands on the cash!’ said the Copt wrathfully.

‘The Tree is cursed,’ said Sheikh Isa. ‘Anyone can see that. Otherwise, why would it be lying on its side?’

‘Old age?’

Sheikh Isa brushed this aside.

‘The question is: why has it been cursed? And the answer is obvious. The Tree fell down a year ago. At exactly the time,’ said Isa with emphasis, ‘that they began to build this new city.’

‘So?’

‘Well, it’s plain, isn’t it? God doesn’t want them to build the city. It’s an abomination to him. So he cursed the Tree to show us his anger.’

‘Why does he abominate the city?’

‘I don’t presume to know God’s mind, but I can make a guess. It’s to be a City of Pleasure. That’s what they say, don’t they? Now God is not against pleasure, but I think his idea of pleasure may well be different from that of the Pashas. Do you think he wants to see such a holy place turned into a Sodom and Gomorrah?’

‘Holy place?’

‘Not here,’ said Sheikh Isa impatiently. ‘The Birket-el-Hadj.’

‘Ah, of course!’

The Birket-el-Hadj was the traditional rendezvous for the Mecca caravan. It was about three miles north of Matariya.

‘Do you think God wants a place like that just where they should be beginning to put their thoughts in order for the Holy Journey?’

‘Perhaps not. But, of course, fewer and fewer people are travelling that way now. They prefer to go by train—’

‘Train?’ roared Sheikh Isa, almost foaming at the mouth. ‘Go to Mecca by train?’

‘Just to the coast—’

‘Train?’ shouted Sheikh Isa. ‘They heap abomination upon abomination! Shall we stand idly by when God’s will is set at naught? Has he not sent us a sign that all can read? Does not the Fall of the Tree spell the Fall of the City—?’

‘Why don’t you just lock him up?’ said the Belgian uneasily.

‘On what grounds?’

‘Causing trouble.’

‘That’s not an offence.’

‘It bloody is in my eyes. Anyway, doesn’t the Mamur Zapt have special powers?’

‘He does. But it’s wisest if he uses them sparingly.’

‘I reckon it would be pretty wise to nip this thing in the bud. Before it gets out of hand.’

‘You don’t lock up religious leaders just like that.’

‘Religious leader? He’s a potty old village sheikh. Look, Owen, I just don’t understand you. This is a very important job and we’re behind schedule as it is, we’ve got to push things along. This business of the man on the line cost us a day and a half. And now you come along and tell us there’s a problem about a Tree!’

‘I’m just telling you to be careful, that’s all.’

‘Well, all right, we’ll be careful. Hey, I’ve got an idea! If that old man is bothered about the Tree falling down, why don’t we just lift it up again? Prop it up with stays? I could send a truck round, we could use a hoist—’

Matariya, although so near to Cairo, was in many respects a traditional oasis village, half hidden under a mass of palms, banana trees and tamarisks and clustered around an old mosque with crumbling, loop-holed walls and a crazy, tottering minaret. Probably because of the proximity to the gathering place for the Mecca caravan, many of the houses were pilgrims’ houses, their walls brightly decorated with pictures of the journey to Mecca.

Against one of the houses a many-coloured tabernacle had been erected beneath which old men were sitting on a faded carpet. In the middle of the carpet was a dikka, or platform, on which sat Sheikh Isa, intoning the Koran. At the edge of the carpet was a pile of shoes. A blind man was putting his foot into them to try and find his own by the feel.

The dead man’s house was just beyond the tabernacle, recognizable at once from the mourning banners. The mourning was still going on. Owen could hear the women’s voices in the back room, less frantic now, resigned.

A man in a dark suit and a tarboosh, the red, tasselled, pot-like hat of the Egyptian effendi, was just about to go into the house. He saw Owen, smiled and waited.

It was the Parquet man who had come out to the railhead two days before when Owen had been trying to prevent a confrontation over the body. They shook hands.

‘Asif Nimeri.’

‘You’re formally on the case now?’

The other day he had been sent merely because he was one of the duty officers. He was young and fresh and new, which was probably why they had sent him. Anything out of town on a hot day was for the juniors.

‘Yes.’

He looked at Owen curiously.

‘Are you taking an interest?’

‘Not really. Just making sure of some of the incidentals.’

‘Sheikh Isa?’

‘That sort of thing.’

The Parquet man laughed.

‘I think he’s harmless.’

‘So do I, really.’

‘You’re not directly interested in the case, then?’

‘No.’

Asif seemed relieved. Conducting his first case was problem enough without the additional difficulty of the Mamur Zapt.

‘I thought that since I was here I would look in. May I join you?’

‘Of course!’

They stepped into the house. It had only two rooms, the rear one, where the wailing was coming from, and the one they were in. It was small and bare. The only furniture was a mattress rolled up and stacked against the wall and some skins, not cushions, on the floor.

Two men came into the room, an old man, probably the father, and one much younger, the brother, or perhaps brother-in-law, of the dead man.

‘I come at a time of trouble,’ said Asif ceremoniously, ‘but not to add to it.’

‘Your grief is my grief,’ said Owen formally.

The men bowed acknowledgement. The older one, with a gesture of his hand, invited them to sit down. They sat on the skins.

A woman brought them water and a small dish of dates.

Asif complimented their host on the water and Owen praised the dates.

‘The water is good,’ admitted the old man.

‘The dates eat well,’ conceded his companion, ‘though not as well as the dates of Marg.’

‘God is bountiful!’ said Asif.

The men agreed.

Owen, used to the slow pace of Eastern investigation, settled back.

‘Although sometimes,’ said Asif, ‘the yoke he asks us to bear is heavy.’

‘True,’ asserted the old man.

‘Does our friend have a family?’

‘A wife,’ said the old man, ‘and two daughters.’

‘No sons?’ Asif shook his head commiseratingly.

‘The girls are still young.’

Which meant that the family would have to support them for some time yet. It would, but every extra mouth was a burden on the family.

They sat for a little while in silence.

‘Are you tax collectors?’ said the old man suddenly.

‘No!’ said Asif, startled.

‘Oh. We thought you might be.’

‘You come from the city,’ explained the younger man.

‘I am from the Parquet.’

The men clearly did not understand.

‘I am a man of law,’ Asif explained.

‘You are a kadi?’

‘Well, no, not exactly,’ said Asif scrupulously. It was not for a fledgling lawyer to claim to be a judge. Besides, the two systems were quite separate. Kadis were concerned with religious law, the Parquet, after the French model, with the secular and more modern criminal law.

‘Who is he?’ asked the older man, pointing at Owen.

‘I am the Mamur Zapt.’

‘Ah, the Mamur Zapt?’

They had obviously heard of him. Or, rather, they had heard of the post. The position of Mamur Zapt, Head of the Khedive’s Secret Police and his right-hand man, went back centuries. Only things were a bit different now. The Mamur Zapt was no longer the right-hand man of the Khedive; he was the right-hand man of the British, the ones who really ruled Egypt.

‘What brings you here?’

‘My friend has some questions to ask,’ said Owen diplomatically.

‘They are not my questions but the law’s questions,’ said Asif. ‘When a man dies in the way that our friend did, they cannot be left unasked.’

‘True,’ said the old man. ‘Ask on.’

‘The first question,’ said Asif, ‘is why, after the evening meal, when all was dark, did he rise from his place and go out into the night?’

‘I do not know.’

‘Was it to meet someone?’

‘I do not know.’

‘Did he not say?’

The two men looked at each other.

‘All he said was that he had to go out.’

‘Did he often do thus in the evening?’

‘Not often.’

‘Were you not surprised?’

‘We thought he was going to sit with Ja’affar.’

‘Did he often sit with Ja’affar?’

The old man hesitated.

‘Sometimes.’

‘But when he did not return, did you not wonder what had befallen him?’

‘Why should we wonder?’

‘What, a man goes out into the night and does not return, and you do not wonder?’

‘What a man does at night is his own business.’

Owen caught Asif’s eye and knew what he was thinking: a woman.

‘And when the morning came and he still had not returned, you still did not wonder?’

‘We thought he had gone straight to work.’

‘After spending the night with Ja’affar?’

‘Yes.’

‘A strange village, this!’ said Asif caustically. ‘Where the men spend the night with the men!’

The younger man flashed up.

‘Why do you ask these questions?’ he said belligerently.

‘Because I want to know why Ibrahim was killed.’

‘That is our business,’ said the brother. ‘Not yours!’

‘It is the law’s business.’

‘Whose law? The city’s?’

‘There is but one law,’ said Asif sternly, ‘for the city and for the village.’

‘It is the city that speaks,’ retorted the villager.

‘These are backward people!’ fumed Asif, much vexed with himself, as they walked away.

‘The ways of the village are not the ways of the town,’ said Owen.

‘I know, I know! I am from Assiut myself. That is not a village, I know, but compared with Cairo—’

‘You did all right,’ said Owen reassuringly.

‘I should have—’

‘Well, Ja’affar, you work late!’ said Asif.

‘I do!’ said Ja’affar, his face still streaked with sweat.

‘It is not every man who works so long in the fields!’

‘Ah, I’ve not been in the fields. I work at the ostrich farm.’

‘Ostrich farm?’ said Owen.

‘Yes, it’s over by the station. You would have seen it if you’d gone out the other side.’

‘And what do you do at the ostrich farm that keeps you so late?’ asked Asif.

‘I feed the birds. You’d think they could feed themselves, wouldn’t you, only if you don’t give them something late in the afternoon they make such a hell of a noise that the Khedive doesn’t like it.’

‘The Khedive can hear them all the way from Kubba?’

‘So he says.’

Ja’affar removed his skull cap and splashed water over his face. A woman came and took the bowl away.

‘So what is it?’ he said. ‘Ibrahim?’

‘That’s right.’

‘He was a mate of mine. We used to work at the farm together.’

‘The ostrich farm?’

‘Yes. Only then the chance of a job on the railway came along and he took one look at the money and said: “That’s for me!” I warned him. I said: “They don’t give you that for nothing, you know. They’ll make you sweat for it.” And, by God, they did. He used to come back home in the afternoon dead beat. Too tired even to lift a fìnger!’

‘Too tired to go out?’ said Asif. ‘In the evenings?’

Ja’affar was amused.

‘There’s not a lot to go out to in Matariya,’ he said drily.

‘We heard he liked to go out and chat with his friends.’

‘Ah, well—’

‘You, for instance.’

‘He used to occasionally. He’s not done it so much lately. Not since I got married and he—’

He stopped.

‘Found someone more interesting?’

‘Well—’

‘Just tell me her name,’ said Asif.

A man came to the door.

‘Yes, he used to come here,’ he said defiantly. ‘Everyone knows that. And, no, he didn’t come here just to taste the figs from the fig tree. There’s no secret about that, either. What do you expect? A man’s a man, and if his wife—’

‘Did he come here on the night he was killed?’

‘How do I know?’

‘You live here, don’t you?’

‘No, I live on the other side of the mosque.’

He was, it transpired, the woman’s brother, not her husband.

‘She’s lived here alone ever since her husband died.’

Asif asked to speak with her in her brother’s presence. This was normal. It was considered improper to speak to a woman alone. Indeed, it was considered to be on the verge of raciness to speak to a woman at all. Questions to women, during a police investigation, for instance, were normally put through her nearest male relative.

The woman appeared, unveiled. This at once threw Asif into a tizzy. He had probably never seen a woman’s face before, not the face of a woman outside his family. This woman had a broad, not unattractive, sunburned face. Things were less strict in the village than they were in the city and when the women were working in the fields they often left their faces unveiled. Even in the village, Owen had noticed, they did not always bother to veil. Sheikh Isa, no doubt, had his views about that.

She was as defiant as her brother.

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘he used to come here. Why not? It suited him and it suited me.’

Asif could hardly bring himself to look her in the face. Although she obviously intended to answer his questions herself, he continued to direct them to her brother, as he would have done in the city.

‘Did he come on the night he was killed?’

‘Yes.’

‘And’ – he wavered – ‘stayed the night?’

‘He never stayed long.’ She laughed. ‘Just long enough!’

‘Jalila!’ muttered her brother reprovingly.

Asif was now all over the place.

‘How – how long?’ he managed to stutter.

‘How long do you think?’ she said, looking at him coolly.

Owen decided to lend a hand.

‘The man is dead,’ he said sternly.

The woman seemed to catch herself.

‘Yes,’ she said.

‘He died after leaving you.’

‘Yes,’ she said quietly.

‘He left you early. Did he say where he was going?’

‘He said he was meeting someone.’

‘Ah! Did he say who?’

‘No. And,’ said the woman, bold again, ‘I did not ask. I knew it wasn’t a woman and that was all I needed to know.’

‘How did you know it wasn’t a woman?’

‘Because it wouldn’t have been any good,’ she said defiantly. ‘Not after what he’d done with me. I always took good care to see there wasn’t much left. For Leila.’

‘Leila?’

‘That so-called wife of his.’

‘Why so-called?’

She was silent.

Then she said vehemently: ‘He should have married me. Right at the start. Then all this wouldn’t have happened.’

The tabernacle was now empty. The pile of shoes had gone. The square was almost empty. The heat rose up off the sand as if making one last effort to keep the advancing shadows at bay. The smell of woodsmoke was suddenly in the air. The women were about to cook the evening meal.

Owen wondered how late the trains back to the city would continue to run. Asif, too, was evidently reckoning that the day’s work was done, for he said:

‘Tomorrow I shall question the wife’s family.’

They turned aside for a moment to refresh themselves at the village well before committing themselves to the long walk back across the hot fields to the station.

‘It could be a question of honour, you see,’ said Asif, still preoccupied with the case. ‘The wife has been dishonoured and so her family has been dishonoured.’

‘You think one of them could have taken revenge?’

Revenge was the bane of the policeman’s life in Egypt. Over half the killings, and there were a lot of killings in Egypt, were for purposes of revenge. It was most common among the Arabs of the desert, where revenge feuds were a part of every tribesman’s life. But it was far from uncommon among the fellahin of the settled villages too.

‘Well,’ said Asif, ‘he was killed by a blow on the back of the neck from a heavy, blunt, club-like instrument. A cudgel is the villager’s weapon. And, besides—’

He hesitated.

‘Yes?’

‘It looks as if it was someone who knew his ways. Knew where to find him, for instance. Knew he would not be staying. Knew him well enough, possibly, to arrange a meeting. That would seem to me to locate him in the village.’

Owen nodded.

‘And if that’s the case,’ he said, ‘you’re going to have to move quickly. Otherwise the other side will be taking the law into their own hands.’

The trouble with revenge killings was that they had two sides. One killing bred another.

‘Tomorrow,’ promised Asif.

A man came round the corner of the mosque and made towards them. He was, like Asif, an Egyptian and an effendi and wore the tarboosh of the government servant. Unlike him, however, and unusually for the time, he wore a light suit not a dark suit and was dressed overall with a certain sharpness. Everything about him was sharp.

He recognized Owen and gave him a smile.

‘Let me guess,’ he said; ‘the railway?’

He turned to Asif.

‘Asif,’ he said softly. ‘I am sorry.’

Asif looked at him in surprise.

‘They have asked me to take over. Why? I do not know. But it is certainly no reflection on you.’

Asif was taken aback.

‘But, Mahmoud, I have only just—’

‘I know. Perhaps they have something more important in mind for you.’

Asif swallowed.

‘I doubt it,’ he said bitterly.

He got up from the well.

‘I will put the papers on your desk,’ he said, and walked off.

Owen made a movement after him but Mahmoud put a hand on his arm.

‘Let him go,’ he said. ‘It’s better like that.’

‘He was doing all right,’ said Owen.

‘I think he’s promising,’ said Mahmoud. He sighed. ‘I wish they wouldn’t do things like this. It hurts people’s pride.’

Mahmoud El Zaki was a connoisseur in pride. That was true of most Egyptians, thought Owen, but it was especially true of him. Proud, sensitive, touchy – all of them qualities likely to be rubbed raw by the situation that Egyptians were in: subordination of their country to a foreign power, subordination in government, subordination in social structure.