Полная версия

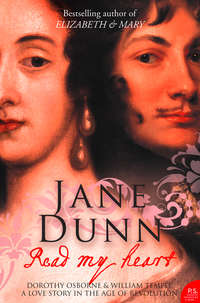

Read My Heart: Dorothy Osborne and Sir William Temple, A Love Story in the Age of Revolution

It was also while he was in Paris in its rebellious mood that William discovered the essays of Montaigne† and perhaps even came across some of the French avant-garde intellectuals of the time. The most contentious were a group called the Libertins, among them Guy Patin, a scholar and rector of the Sorbonne medical school, and François de la Mothe le Vayer, the writer and tutor to the dauphin, who pursued Montaigne’s sceptical philosophies to more radical ends, questioning even basic religious tenets. Certainly from the writings of Montaigne and from the intellectual energy in Paris at the time – perhaps even the company of these controversial philosophers – William learned to enjoy a distinct freedom of thought and action that reinforced his natural independence and incorruptibility in later political life.

Just across the Channel, events were gathering apace. By January 1649 in London the newly sifted parliament had passed the resolutions that sidelined a less compliant House of Lords, allowing the Commons to ensure the trial of the king could proceed. There was terrific nervousness at home; even the most fiery of republicans was not sure of the legality of any such court. In a further eerie echo of the fate of his grandmother, Mary Queen of Scots, Charles was brought hastily to trial, all the while insisting that the court had no legality or authority over him. On 20 January 1649 he appeared before his accusers in the great hall at Westminster. Like his grandmother too he had dressed for full theatrical effect, his diamond-encrusted Order of the Star of the Garter and of St George glittering majestically against the sombre inky black of his clothes. Charles was visibly contemptuous of the cobbled-together court and did not even deign to answer the charges against him, that he had intended to rule with unlimited and tyrannical power and had levied war against his parliament and people. He refused to cooperate, rejecting the proceedings out of hand as manifestly illegal.

All those involved were fraught with anxieties and fear at the gravity of what they had embarked on. As the tragedy gained its own momentum, God was fervently addressed from all sides and petitioned for guidance, His authority invoked to legitimise every action. Through the fog of these doubts Cromwell strode to the fore, his clarity and determination driving through a finale of awesome significance. God’s work was being done, he assured the doubters, and they were all His chosen instruments. It was clear to him that Charles had broken his contract with his people and he had to die. His charismatic certainty steadied their nerves.

The death sentence declared the king a tyrant, traitor, murderer and public enemy of the nation. There were frantic attempts to save his life. From France, Charles’s queen Henrietta Maria had been busy in exile trying to rally international support for her husband. Louis XIV, a boy king who was yet to grow into his pomp as the embodiment of absolute monarchy, now sent personal letters to both Cromwell and General Fairfax pleading for their king’s life. The States-General of the Netherlands also added their weight, all to no avail.

Charles I went to his death in the bitter cold of 30 January 1649. He walked from St James’s Palace to Whitehall, his place of execution. Grave and unrepentant, he faced what he and many others considered judicial murder with dignity and fortitude. As his head was severed from his body, the crowd who had waited all morning in the freezing air let out a deep and terrible groan, the like of which one witness said he hoped never to hear again. Charles’s uncompromising stand, the arrogance and misjudgements of his rule, the corrosive harm of the previous six years of civil wars, had made this dreadful act of regicide inevitable, perhaps even necessary, but there were few who could unequivocally claim it was just. There was a possibly apocryphal story passed on to the poet Alexander Pope, born some forty years later, that Cromwell visited the king’s coffin incognito that fateful night and, gazing down on the embalmed corpse, the head now reunited with the body and sewn on at the neck, was heard to mutter ‘cruel necessity’,11 in rueful recognition of the truth.

For the first time, the country was without a king. The Prince of Wales, in exile in The Hague, was proclaimed Charles II but by the early spring the Rump Parliament had abolished the monarchy and the House of Lords. England was declared a commonwealth with all authority vested in the Commons. The brutal suppression of the Irish rebellion continued through the summer with particularly gruesome massacres at Drogheda and Wexford and the following year, 1650, saw the Scottish royalist resistance broken up by parliamentarian forces. Slowly the bloodshed was being brought to an end and life returned to a new kind of normality.

Most important for the Osborne family in unhappy exile in St Malo was the deal they managed to negotiate with the new government whereby they were allowed to return to their estate at Chicksands on the payment of a huge fine, possibly as much as £10,000 (more than a million by today’s value). This concession might have been in part due to some helpful intervention from Lady Osborne’s brother, the talented garden planner and member of parliament Sir John Danvers. He had become one of Cromwell’s loyal colleagues who served on the commission to try the king and, unlike many, had not baulked at putting his signature to the infamous death warrant. In February 1649 he was appointed one of the forty councillors of state of the new commonwealth, a position he kept until its dissolution in 1653. Dorothy and her mother had stayed with him in his house in Chelsea when she was younger and it is likely he would have exerted whatever influence he could to have their ancestral home restored to them at whatever cost.

So Dorothy and her family returned to Bedfordshire, their lives completely changed and their prospects dimmed. Dorothy’s father was aged and unwell and her mother exhausted by the heavy toll of the last few years of exile, impoverishment and uncertainty. She would only live for another year or so, dying, aged sixty-one, in 1651.

For Dorothy, return to the family home was a mixed blessing. Once again she was subject to the demands made on a dutiful unmarried daughter. After her mother’s death the organisation of the household fell to her, as did the care and companionship of her father. Her favourite brother Robin, who had shared her adventures on the Isle of Wight, was still around and unmarried, as was Henry, eleven years her senior. As men they could come and go at will. Her only sister Elizabeth, the eldest of the family, had married at the age of twenty-six and, after just six years of marriage, died in 1642, before the first civil war. Dorothy was only fifteen at the time and remembered her as a clever bookish girl, cut down far too young, perhaps by puerperal fever, that scourge of childbearing women: ‘my Sister whoe (I may tell you too and you will not think it Vanity in mee) had a great [deale] of witt and was thought to write as well as most women in England’.12 Dorothy’s eldest brother John had also married and appeared occasionally at Chicksands, the estate he was to inherit on their father’s death.

Dorothy professed herself unconcerned at the loss of her family’s fortune: ‘I have seen my fathers [estate] reduced [from] better then £4000 to not £400 a yeare and I thank god I never felt the change in any thing that I thought necessary; I never wanted nor am confident I never shall.’13 This was brave talk, for the family’s impoverishment made her marriage to a man of good fortune all the more pressing. The family matchmakers increased their efforts: Dorothy appeared to entertain their ideas but in fact merely procrastinated, prevaricated and in the last resort refused. She found her seclusion on the family estate increasingly tedious. Paying visits to elderly neighbours and keeping all talk small had limited appeal when she had been exposed to adventure and love. ‘I am growne soe dull with liveing in [Chicksands] (for I am not willing to confess that I was always soe),’14 she admitted.

As a young woman, Dorothy chose to try to live a good life, and while she was unmarried and waiting on her family’s needs this was inevitably a dull one too. She attempted to reconcile her own conduct with the highest standards of her family’s expectations and the precepts of the Bible. She turned to the religious writer Jeremy Taylor, ‘whose devote you must know I am’,15 for his meditations on how to live a useful Christian life. Yet Taylor, in urging a lofty disregard for public opinion, ‘he that would have his virtue published, studies not virtue, but glory’,16 accepted that women’s lives were more constrained. Dorothy, like every other young woman of her time, felt she had to be careful of her reputation. Her and her family’s honour, her marriage prospects, her place in society, all depended on it. She explained this rather defensively in a letter to William Temple: ‘Posibly it is a weaknesse in mee, to ayme at the worlds Esteem as if I could not bee happy without it; but there are certaine things that custom has made Almost of Absolute necessity, and reputation I take to bee one of those.’17

As an emotionally impetuous young man living with greater freedom of conduct than any young woman of his time, William might have wished that Dorothy was more reckless but in fact she was merely expressing a cast-iron truth that most other young unmarried women in her position had learned from the cradle. Lady Halkett, who was to live an unusually adventurous adult life, was equally obedient and careful while young to avoid accusations of ‘any immodesty, either in thought or behavier … so scrupulous I was of giving any occation to speake of mee, as I know they did of others’.18

The social and moral structures of men’s and women’s lives were based on the teaching and traditions of Christian religion and to a lesser extent the philosophy of the classical authors of Greece and Rome. The Church’s view of women was well established and deeply embedded in society’s expectations of human behaviour. The Bible provided the authority. It was read daily and studied closely, making depressing reading for any young woman seeking a view of herself in the larger world. In the Old Testament woman was a mere afterthought of creation. Apart from rare and shining examples, like the wise judge Deborah and the beneficent Queen of Sheba, they had little significance beyond being subjects in marriage and mothers of men. When it reared its head at all, female energy was more often than not duplicitous, contaminatory and dark.

The poet Anne Finch,* of a younger generation than Dorothy, still smarted under the limited expectations for girls, comparing the current generation unfavourably to the paragon Deborah:

A Woman here, leads fainting Israel on,

She fights, she wins, she tryumphs with a song,

devout, Majestick, for the subject fitt,

And far above her arms [military might], exalts her witt,

Then, to the peacefull, shady Palm withdraws,

And rules the rescu’d Nation with her Laws.

How are we fal’n, fal’n by mistaken rules?

Debarr’d from all improve-ments of the mind,

And to be dull, expected and dessigned;

… For groves of Lawrell [worldly triumphs], thou wert

never meant;

Be dark enough thy shades, and be thou there content.19

A thoughtful girl’s reading of the classics in search of images of female creativity or autonomy was almost as unedifying. Unless they were iconic queens such as the incomparable Cleopatra, women of antiquity were subject to even more containment than their seventeenth-century English counterparts. The main role of Greek and Roman women was as bearers of legitimate children and so their sexuality was monitored and feared. Women had to be tamed, instructed and watched. Traditionally they were expected to be silent and invisible, content to live in the shadows, their virtues of a passive and domestic kind.

Dorothy had certainly grown up unquestioning in her belief in God and duty to her parents, expecting to obey them without demur, particularly in the crucial matter of whom she would marry, and wary of drawing any attention to herself. There was more than an echo down the centuries of the classical Greek ideal: that a woman’s name should not be mentioned in public unless she was dead, or of ill repute, where ‘glory for a woman was defined in Thucydides’s funeral speech of Pericles as “not to be spoken of in praise or blame”’.20 The necessity of self-effacement and public invisibility was accepted by women generally, regardless of their intellectual or political backgrounds. The radical republican Lucy Hutchinson, brought up by doting parents to believe she was marked out for pre-eminence, insisted – even as she hoped for publication of her own translation of Lucretius – that a woman’s ‘more becoming virtue is silence’.21

The Duchess of Newcastle was another near contemporary of Dorothy’s but she was one of the rare women of her age who refused to accept such constraints on her sex. Her larger than life persona, however, and her effrontery in publishing her poems and opinions with such abandon attracted violent verbal assaults on her character and sanity. The cavalier poet Richard Lovelace* inserted into a satire, on republican literary patronage, a particularly harsh attack on the temerity of women writers, possibly aimed specifically at the duchess herself, whose verses were published three years prior to this poem’s composition:

… behold basely deposed men,

Justled from the Prerog’tive of their Bed,

Whilst wives are per’wig’d with their husbands head.

Each snatched the male quill from his faint hand

And must both nobler write and understand,

He to her fury the soft plume doth bow,

O Pen, nere truely justly slit till now!

Now as her self a Poem she doth dresse,

Ands curls a Line as she would so a tresse;

Powders a Sonnet as she does her hair,

Then prostitutes them both to publick Aire.22

It was no surprise that even someone as courageous and individual as the Duchess of Newcastle should show some trepidation at breaking this taboo, addressing the female readers of her first book of poems published in 1653 with these words: ‘Condemn me not as a dishonour of your sex, for setting forth this work; for it is harmless and free from all dishonesty; I will not say from vanity, for that is so natural to our sex as it were unnatural not to be so.’23

As a young woman, Dorothy Osborne was intrigued by the duchess’s celebrity, a little in awe of her courage even, for Dorothy too had a love and talent for writing, owned strong opinions and was acutely perceptive of human character. Eager as she was to read the newly published poems (this was the first book of English poems to be deliberately published by a woman under her own name), Dorothy recoiled from the exposure to scorn and ridicule that such behaviour in a woman attracted. And she joined the general chorus of disapproval: ‘there are many soberer People in Bedlam,’24 she declared. Perhaps the harshness of this comment had something to do with the subconscious desire of an avid reader and natural writer who could not even allow herself to dream that she could share her talents with an audience of more than one?

Writing in the next generation, Anne Finch, who did publish her poems late in her life, knew full well the way such presumption was viewed:

Alas! a woman that attempts the pen,

Such an intruder on the rights of men,

Such a presumptuous Creature, is esteem’d,

The fault, can by no vertue be redeem’d.

They tell us, we mistake our sex and way;

Good breeding, fassion, dancing, dressing, play

Are the accomplishments we shou’d desire;

To write, or read, or think, or to enquire

Wou’d cloud our beauty, and exaust our time;

And interrupt the Conquests of our prime;

Whilst the dull mannage, of a servile house

Is held by some, our utmost art, and use.25

Secluded in the countryside, Dorothy cared for her ailing father, endured the social rituals of her neighbours and read volume upon volume of French romances. The highlight of her days and the only, but fundamental, defiance of her fate was her secret correspondence with William Temple. In this Dorothy engaged in the creative project of her life, one that absorbed her thoughts and called forth every emotion. Through their letters they created a subversive world in which they could explore each other’s ideas and feelings, indulge in dreams of a future together and exorcise their fears. Dorothy’s pleasure in the exercise of her art is evident, and she had no more important goal than to keep William faithful to her and determine her own destiny through the charm and brilliance of her letters.

William and Dorothy started writing to each other from the time they were first parted in the later months of 1648 when they were both in France. Martha, William’s younger sister, wrote that he spent two years in Paris and then exploring the rest of the country, by the end of which time he was completely fluent in French. His days drifted by pleasantly enough, playing tennis, visiting other exiles, looking at chateaux and gardens, reading Montaigne’s essays, practising his own writing style and thinking of love. He returned to England for a short while, when Dorothy and her family were also once more resident on the family estate at Chicksands, possibly managing a quick meeting with her then, before he ‘made another Journey into Holland, Germany, & Flanders, where he grew as perfect a Master of Spanish’.26

The surviving letters date from Christmas Eve 1652. It is from this moment that Dorothy’s emphatic and individual voice is suddenly heard. The distant whisperings, speculation and snatches of commentary on their thoughts and lives become clear stereophonic sound as Dorothy, and the echo of William in response, speaks with startling frankness and clarity. The three and a half centuries that separate them from their readers dissolve in the reading, so recognisable and unchanging are the human feelings and perceptions she described. This is the voice even her contemporaries recognised as remarkable, the voice Macaulay fell in love with, of which Virginia Woolf longed to hear more: the voice that has earned its modest writer an unassailable eminence in seventeenth-century literature.

Only the last two years of their correspondence survived, one letter of his and the rest all on Dorothy’s side, but her letters are so responsive to his unseen replies that the ebb and flow of their conversation is clear and present as we read. As William’s sister recognised, the reversals of fortune, much of it detailed in these letters, made their courtship a riveting drama in itself. In order for their love to defy the world and finally triumph, they endured years of subterfuge, secret communication, reliance on go-betweens, stand-up arguments against familial authority, subtle evasions and downright refusals of alternative suitors. The progress of their relationship is revealed in this extraordinary collection of love letters.

As artefacts they are remarkable enough, beautifully preserved by Dorothy’s family over the years and now cared for by the manuscript department at the British Library. Most of the letters are written on paper about A4 size folded in two and with every margin, any spare inch, covered by Dorothy’s elegant, looping script. But it is what they contain that makes them exceptional: frank and conversational in style, the writer’s character and spirit are clear in the confiding voice that ranges widely over daily life and desires, social expectations, and a cavalcade of lovers, family and friends. Sharp, intelligent, full of humour, it is as if Dorothy sits talking beside us. This was exactly the effect she sought to have on William, for these letters were the only way that she could communicate with him through their years of separation, keeping him bound to her and believing in their shared dream.

Dorothy’s first extant letter is a reply to one by William, written on his return to England and after a lengthy gap in their communication. He had previously wagered £10 that she would marry someone other than him and had written, claiming his prize in an attempt to discover obliquely if she remained unattached, even still harbouring warm feelings for him. This was an early indication of his exuberant gambling nature for his bet, at the equivalent of more than £1,000, was significant for a young man who had only just finished his student days. He referred to himself as her ‘Old Servant’, ‘servant’ being the term she and her friends used to refer to anyone actively courting another, or being themselves courted. This was a fishing letter that could not have made his romantic intent more clear.

This was all Dorothy had been waiting for. William had been silent for so long, she had feared he had forgotten her. In her lonely fastness in the country, tending to her father and fending off the suitors pressed on her by her family, his longed-for letter arrived unannounced, revealing clearly his continued interest. All her unexpressed intelligence and pent-up feelings suddenly had a focus again. The brilliance and intensity of her letters expressed this force of emotion and her longing for a soulmate to whom she could talk of the things that really mattered. Later, once she was married, William and others complained that Dorothy’s letters lacked the passion and energy of these written during her courtship. How could they not? These letters were most importantly her means of enchantment, the only recourse she had to seduce his heart and keep him faithful through the long years of enforced separation.

At first her response was careful and controlled. Her handwriting is at its most elegantly formal and constrained. None of her subsequent letters, when she was confident of his feelings, was quite so neatly and carefully written. A great deal of thought has gone into her reply and Dorothy’s answer is masterly in its covert disclosure of her pleasure in hearing from him again, her delight that he still seems to care, the constancy of her feelings and her continuing unmarried state. Despite the fundamental frankness and honesty, her style is full of subtle charm and flirtatious teasing. His revelation of his interest in her had restored her power. She started as she meant to continue, with the upper hand:

Sir

You may please to Lett my Old Servant (as you call him) know, that I confesse I owe much to his merritts, and the many Obligations his kindenesse and Civility’s has layde upon mee. But for the ten poundes hee claims, it is not yett due, and I think you may do well (as a freind) to perswade him to putt it in the Number of his desperate debts, for ’tis a very uncertaine one [she is unlikely to claim it, i.e. marry]. In all things else pray as I am his Servant.

And now Sir let mee tell you that I am extreamly glad (whoesoever gave you the Occasion) to heare from you, since (without complement [without being merely courteous]) there are very few Person’s in the world I am more concer’d in. To finde that you have overcome your longe Journy that you are well, and in a place where it is posible for mee to see you, is a sattisfaction, as I whoe have not bin used to many, may bee allowed to doubt of. Yet I will hope my Ey’s doe not deceive mee, and that I have not forgott to reade. But if you please to Confirme it to mee by another, you know how to dirrect it, for I am where I was, still the same, and alwayes Your humble Servant27

Her request that he write again to reassure her and her signing off ‘for I am where I was, still the same, and alwayes Your humble Servant’ is eloquent of how nothing for her has changed since their last passionate meeting and, she implied, nothing would change, however many eligible suitors, however great the familial pressure. William himself may have had his sexual adventures as a young man abroad, but his heart too had remained constant over the last four years, despite the competing charms of young women with greater fortunes promoted by his family. His sister Martha recalled Dorothy’s and William’s single-minded commitment to each other over the years, to the confounding of some of their friends and all their family, the general thought being that they were negligent of their duty to marry well and disrespectful to their parents: ‘soe long a persuit, though against the consent of most of her friends, & dissatisfaction of some of his, it haveing occasion’d his refusall of a very great fortune when his Famely was most in want of it, as she had done of many considerable offers of great Estates & Famelies’.28