Полная версия

The Great Hollenberg Saga

and branching-off to modern day transatlantic life.

This Caused it All

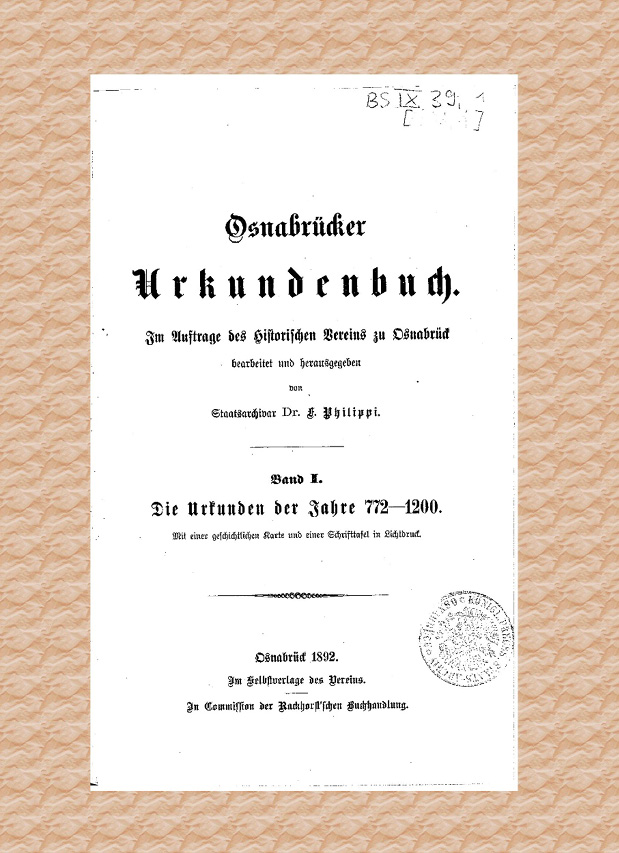

The documentation of old Church archives from the Bishopric of Osnabrück

covering the period of 772 A.D. to 1200 A.D. including the area of Tecklenburg:

Our place, Our Land, Home for Generations of Hollenbergs working the Soil.

Where many others were stampeding the ground for 1000 years and more, like:

• misc. Germanic tribes

• the Romans

• the Saxons

• the Franks (Franconians)

• other European strangers.

Our place: That is the parental home of two boys --- Erich and Heinz ---. Erich, the younger and now the owner, while Heinz, the older moved on becoming a world-citizen with emotional ties to the territory and its people and across the Atlantic.

Our place: That is a location along the hills of the “Teutoburger Wald” (a forest) separating the heartland of the current province of Westphalia in the south (“Münsterland”) from the low plains in North-Germany. A region still very peaceful and rural with fine, old farmhouses a largely unspoiled landscape of forests and fertile farm land as well as marsh and heath.

And last, but not least, plenty of footprints of history, from prehistoric graves and early settlements and many signs of civilization throughout time. Around 800 B.C. iron began to replace copper; and later great tribal move-ments took place from north to south, with the Goth, the Cimbri, the Teutons, and the Vandals, while the Romans were pushing north.

Where It All Began

The only reliable written testimonies from this period were made available by Roman writers like Tacitus. In his book “Germania”, he covers land and people of our area, specifically the Varus battle at 9 AD, which happened to occur only a few miles away.

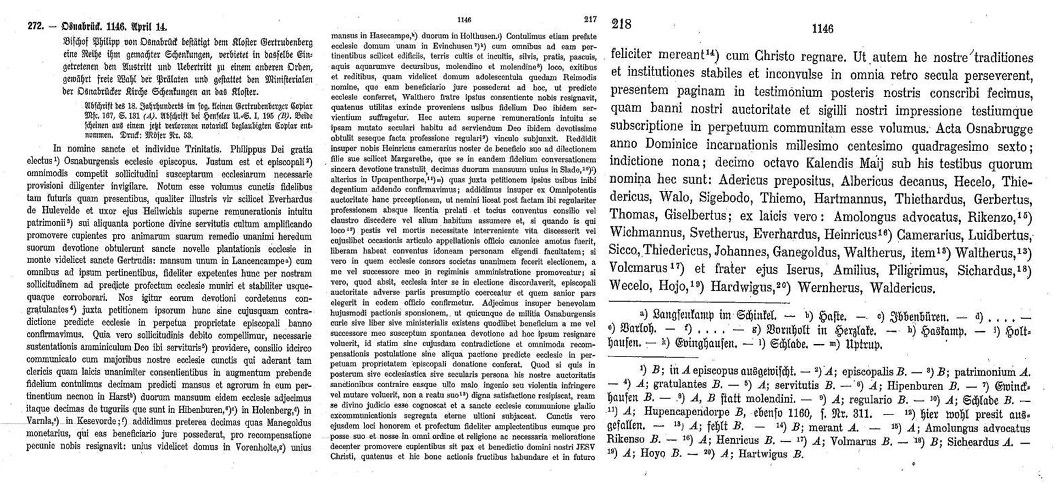

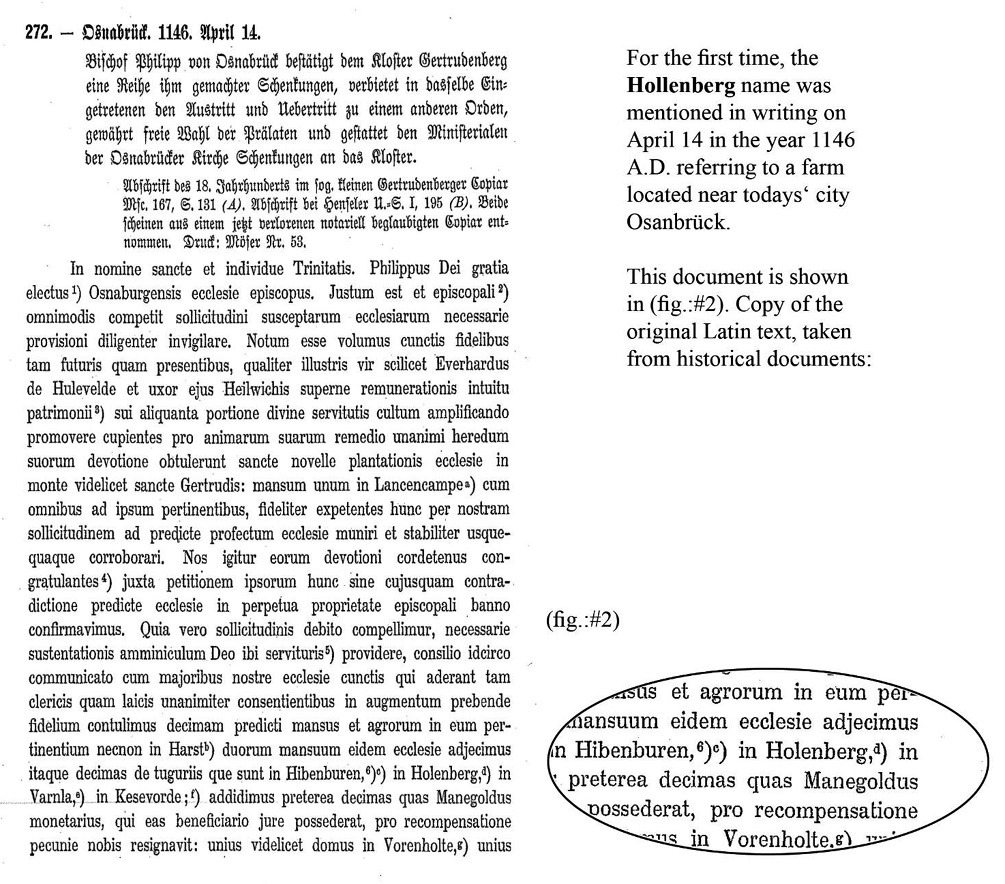

Our part of our history began with a little note in an old history book, a document written in Latin and found in the State Record Office of Lower-Saxony. The particular details were issued by Bishop Philipp of Osnabrück on 14th, April, 1146 A.D. as shown below:

(fig.: #1)

(fig.: #2)

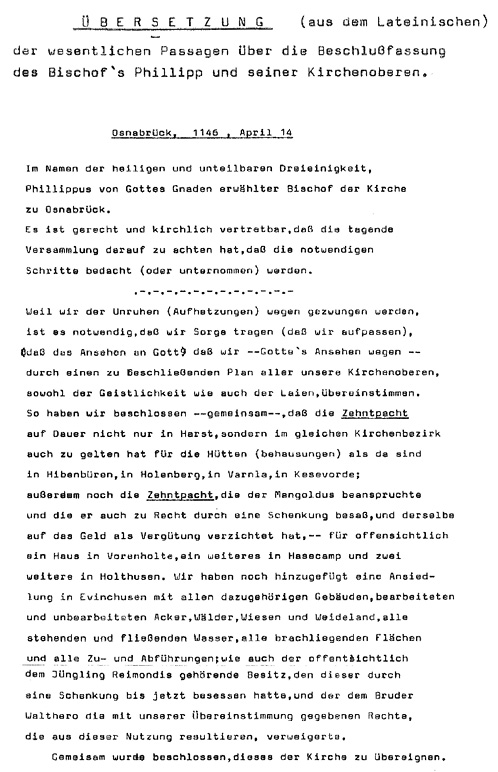

Translation of fig. # 2 from Latin into German

All official dealings of the time were negotiated and recorded in Latin, since the local population spoke only an old “Low-German” idiom, which turned later into a Low-German “Plattdeutsch”.

Written documents of Germanic tribes of that time are rarely available with only very few examples, like the EDDA story of the North-Germanic “Vikings”. Thus, using my own knowledge of Latin with some third party corrections, I am giving a translation of the most relevant sections of the resolution from April 14 of the year 1146 A.D.

Translation from Latin of Documents of the

Office of the Bishop of Osnabrück Issued on April 14-th

of the Year 1146 A.D.

This document refers to a resolution of the same day by Bishop Phillip and the Superiors of the Christian Church of the bishopric of Osnabrück in Saxony. The resolution goes as follows:

“In the name of the holy and indivisible Trinity, Phillippus of God`s Grace, chosen Bishop of the Church at Osna-brück -----“. -----“It is just and ecclesiastically justifiable, that the acting assembly pays attention to the fact, that necessary steps are to be considered (or to be undertaken).”

----------------------------------------

“Because of the unrest and agitation, we are concerned out of necessity, and for God’s prestige; we, all

Superiors of the Christian Church as there are the clergy as well as all the lay”.

(Explanation: The bishops had only moderate success in getting along with local people.)

“Such, we have jointly concluded, that the tithe (= definition: = a tenth part of the yearly proceeds arising from lands and from personal industry of the inhabitants for the support of the clergy and the Church.) is permanently to be levied not only in Harst, but in the same church district also for the dwellings in Hibbenbüren, in Holenberg, in Varula, in Kesevorde; furthermore, also the tithe for a house in Vorenholte, which was rightfully claimed by Mangoldus as part of a donation, and for which the same forgave all monetary compensation, and also for one in Hasencamp and two other in Holthusen. We also add a settlement in Evinchusen including all buildings, farm-land, forests, meadows, all fallow-land, and all routes, coming and going,“

“It was jointly concluded, that all the above is to be transferred to the Church“ (Translation by: Heinz Niederste Hollenberg)

Here is stated that Bishop Phillippus and the Superiors of the Christian Church of the bishopric of Osnabrück decide in the name of the Holy and Indivisible Trinity to permanently levy the “ tithe” on housings (dwellings) like Hibbenbüren (= today: Ibbenbüren), Holenberg, Varula, Kesevorde and others.

Existing ‘registers of proceeds ‘, dated around 1180, show the income of the Dompropst Lentfried (= an ecclesi-astical principal!). These listings prove that a number of farms of our area, well-known to this day, had to make contributions to the Episcopate in Osnabrück.

Noteworthy is also: The Episcopate of Osnabrück was founded by Charlemagne in 785 AD as the first bishopric in the land of the Saxons. He appointed Bishop Wiho, a disciple of the Apostel Bonifacius, to serve as the first bishop in Osnabrück in the year 804 AD.

All this supports the assumption that these same farms still known today existed indeed, and their families used to live and work there. It is very unusual, that the same family line stayed on, struggled and survived until modern days and show early in the 21st century what happened to the Hollenbergs.

However, before going into particulars, I like to look back into the preceding centuries with additional details about the rich culture and historical events of that region.

Time before A.D. and Early Settlements and Dwellings in the Region

What happened in those earlier times in the country of the Cherusker and the Saxons?

The change from a hunter or fisherman to a resident husband-man or stock-farmer took place quite likely around 2000 BC.

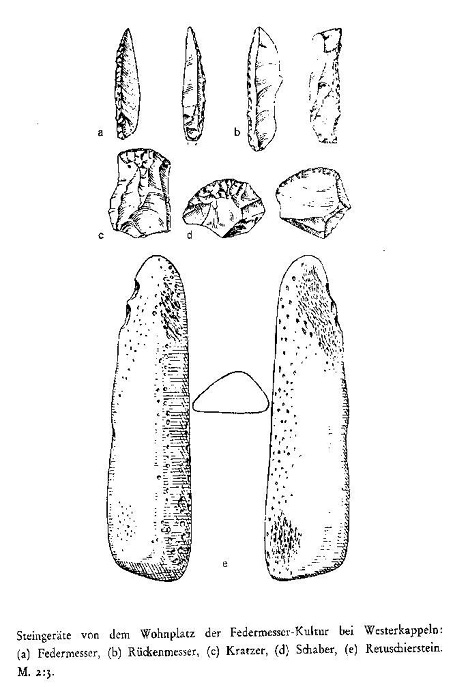

The findings by Dr. Günther and others during the 1950’s and 60’s have shed additional light onto the history of settlements in this region during ancient times. They uncovered traces, vestiges of oval huts with corresponding pits of settlements and workplaces dating back to the hunter and fisherman period.

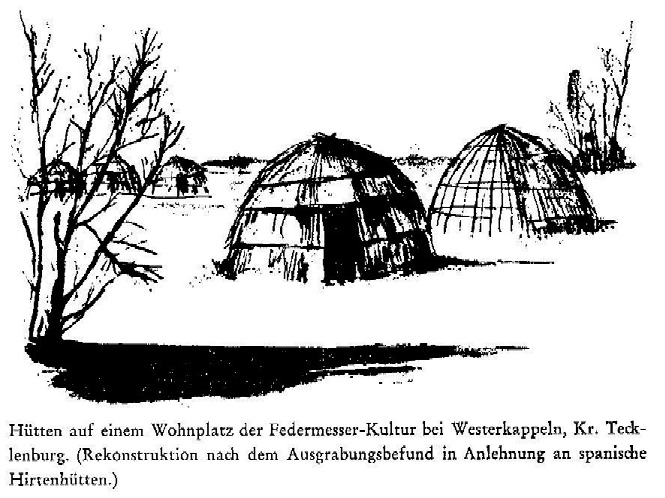

The sketch (fig.:#3), shows a likely reconstruction of these huts, reflecting details of dwellings from the Feather-Knife (Pen-Knife) period near Westerkappeln. (About 9000 B.C. – 8000 B.C.)

This is based on excavation findings similar of Spanish shepherd huts, as shown in a reconstructed ancient fishing hut from the Mediterranean coast of Northern Spain and Southern France.

Early Dwellings from the Feather-Knife Period near Westerkappeln

(fig.: #3)

Huts found on a refuge near Westerkappeln

Miscellaneous stone-tools found in same

excavation near Westerkappeln

Reconstructed ancient Spanish shepherd’s hut..

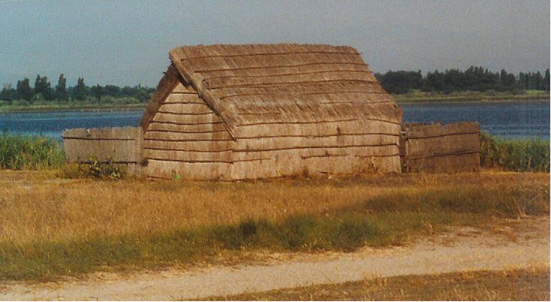

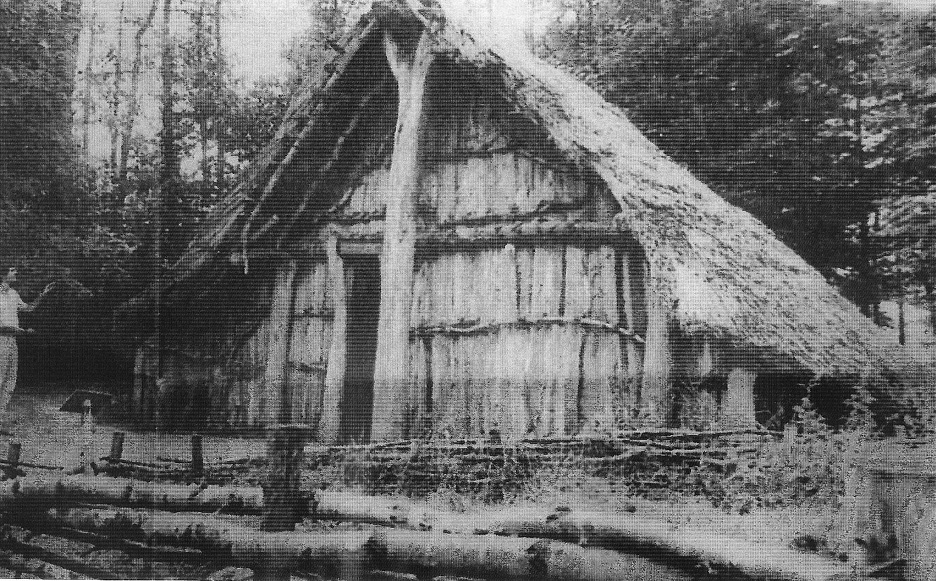

Another typical example of early living quarters (fig.:#4) shows an evolution to a wooden structure. The Archa-eological-Open-Air- Museum in Örlinghausen, near Detmold, has reconstructed this design based upon nearby findings. The building is 69 feet in length (23 m) and 16,5 feet in height (5,5 m), totalling an area of 1200 sq. ft (120 sq. mtr.) Such a structure was build with about 200 oak-trunks and can be assumed typical for the area around 1500 B.C. (See below)

A somewhat of a“luxurious” dwelling of our ancestors at the time.

(fig.:# 4)

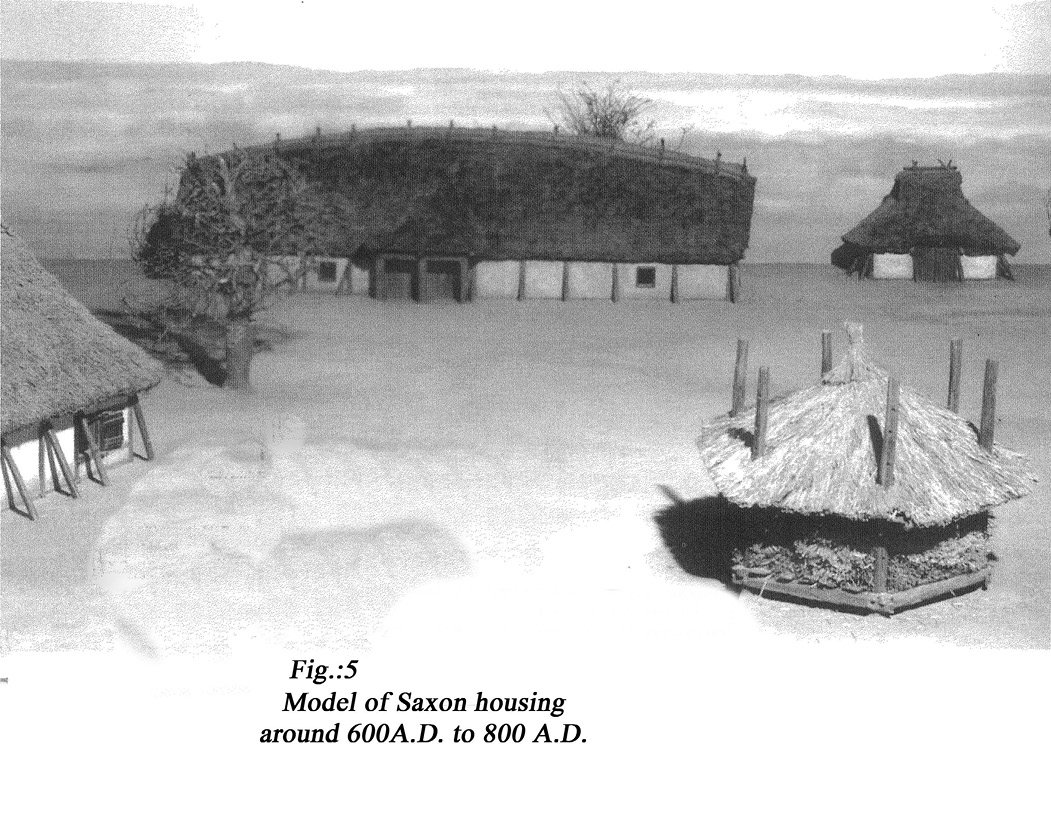

Findings from the period between 600 to 800 AD reveal a Saxon dwelling near Warendorf, Westphalia (fig.:#5) --- a forerunner of the later classical farmhouse throughout Northwest Germany known as the ‘Niedersächsisches Bauernhaus‘ (Lower-Saxony farm house)

All of them had already, as still found today, one thing in-common: men and livestock under a single roof!

The Battle nearby at 9 A.D. with the Romans

And now let’s jump into the period when the Roman Empire was at its peak, around the birth of Christ.

It was the time when a number of independent Germanic tribes, which had settled in Europe between the Danube in the South and the North- and Baltic- Seas, and between the Rhine in the West and the Vistula (=Weichsel) in the East. It was the time when the transition began from migratory hunting and herding to agriculture and village life.

During this period of transformation, the Romans began to expand beyond their historical frontiers into just those core Germanic territories to subdue those traditional “clan” structures and their people there.

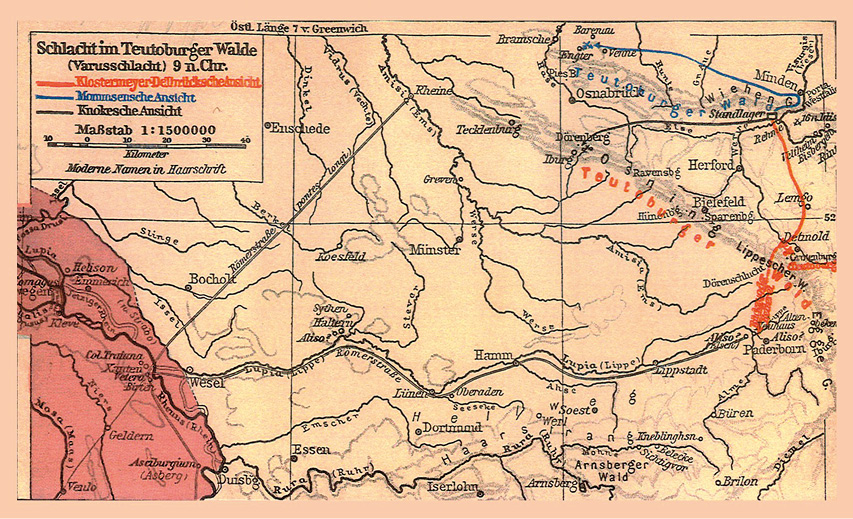

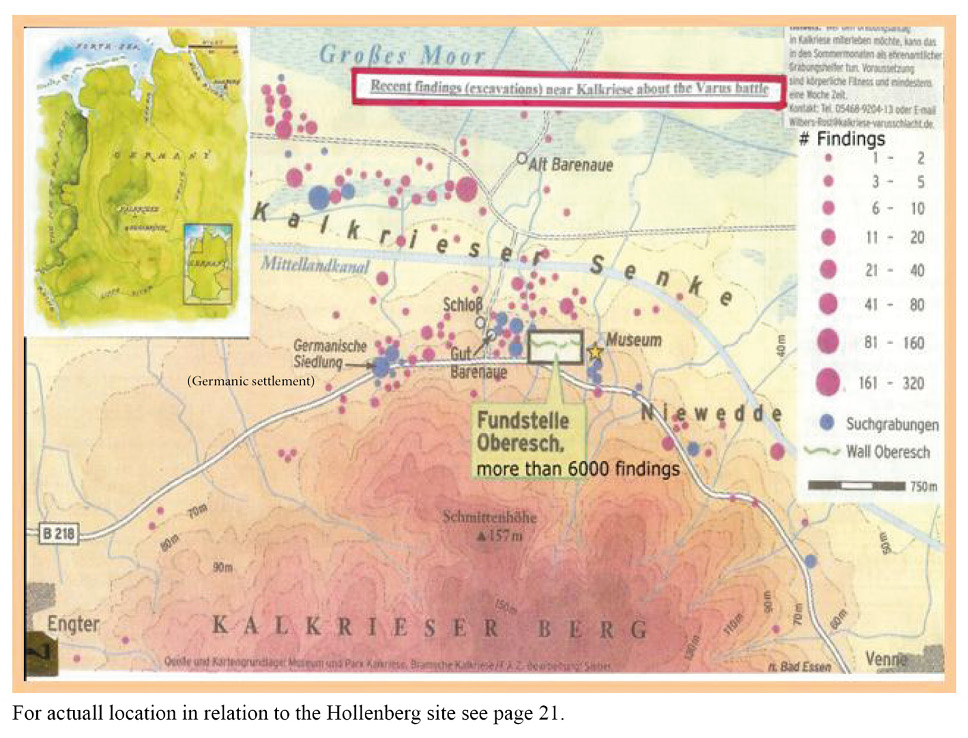

The only reliable written testimony from this period is made available by Roman writers like Tacitus. In his book “Germania”, he covers land and people of our area with particular details of the “Varus” battle from 9 AD. The actual location of the battle site has been a subject of dispute for several hundred years and was argued by many historians. (fig.: #6)

The “blue” line shows the theory of the historian Mommsen from the late 19th century. Others had different ideas, like Klostermeyer-Delbrück, Knocke, etc.

However, it took more than 100 years to give proof to Mr. Mommsen, pointing to a place named “Kalkriese” which is only a few miles away from our “Holenberg” site.

The Varus Battle near Osnabrück at 9 A.D.

between Roman Legions under Publius Quinctilius Varus

and Arminius Leading the Germanic tribes

(fig.:# 6)

It might be noted that, in the September issue of 2005, even the “Smithonian” Magazine covered this par-ticular battle rather detailed, under the title: “The Ambush that Changed History”.

The site was lost and had been argued about for over 1000 years. It was rediscovered with a simple metal detector coincidentally by Tony Clunn, a British Army officer, in 1987.

It is reported that, when the news about this bloody event reached Rome, Emperor Augustus made his rather fa-mous outcry: “Quintilius Varus! Give me my legions back”.

At that point and place, the Roman Empire lost 3 legions, amounting to an equivalent of 18000 to 20000 soldiers.

It was this particular battle, spearheaded by the Germanic tribe of the Cherusci under the leadership of their com-mander, named Arminius, which halted the spread of the Roman Empire, thus marking the turning of the tide of

Rome’s struggle with the Germanic tribes. The defeat took place in a 360-foot-hill area where the “Teutoburger Wald” slopes down into the North-German plain.

Here is proof of a pivotal event in Central-European history, where 3 Roman crack units were annihilated.

“Nothing was more bloody than this defeat in those swamps and woods, nothing as unbearable as the insolence of those Barbarians”, Florus, a Roman reporter, wrote.

This battle took place in close proximity to Osnabrück at “Kalkriese”, within sounding distance of the living quarters of our ancestors. (fig.: #7)

Where the Romans Lost against Arminius

Although many historians have speculated for several hundred years about the actual site, this uncertainty has now been put to rest. Quite a few Roman writers gave different accounts and no specific details about this event. Other neutral information or descriptions from Germanic parties were not existent. However, we now have proof of the historical site.

Many artefacts were found and have been put on display, while the excavation activities are still going on.

(fig.: #8)

Yoke fittings (bronze )

- pendent of horse harness

- Part of snaffle

- strap items ( bronze )

Most of the work is currently being coordinated by the University of Osnabrück.

All in all, the old homestead is in a territory rich in culture and full of historical events.

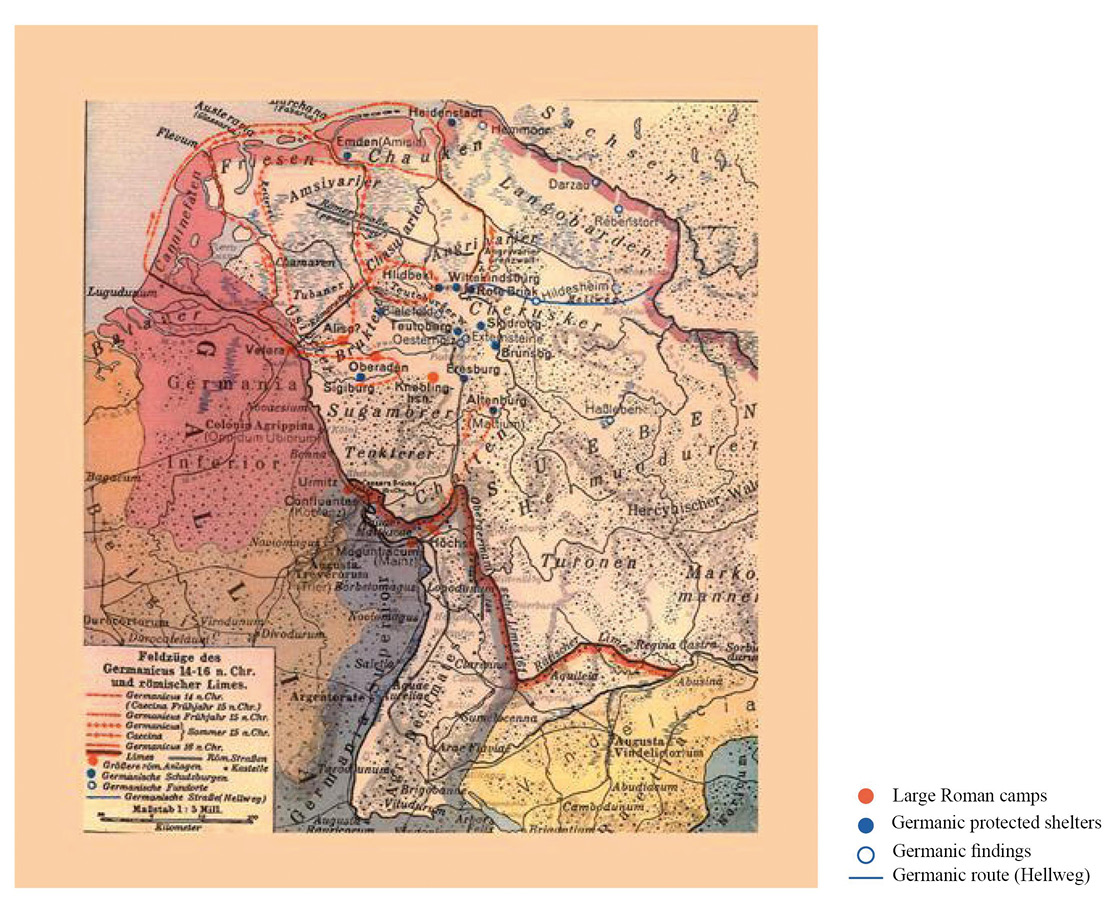

A few years would pass before Germanicus ordered around 14-16 AD another Roman army to the former battle field. He ordered 6 legions (twice the size of the Varus force) into the area to restore Roman military honour, to pursue the Germanic tribes still under the leadership of Arminius, and to bury the human remains of the earlier battle.

However, the whole campaign did not give him the upper hand over his enemies.

Germanicus was no match for the agile tactics of his opponent Arminius in any of the numerous skirmishes.

After several bloody clashes, he decided to withdraw to the Rhine-Valley.

Towards the end of 16 AD, the new Emperor Tiberius recalled Germanicus. The fortifications of the “Limes” along the Rhine-Valley were to be the northern points of Roman military activities.

This all resulted in abdicating the plans of the Empire to conquer German territory, and instead created a milita-rized buffer zone, the “Limes”, between the Germanic and Latin cultures that lasted for about 2000 years. (fig.:#9)

The tremendous burden on the Treasury and the bloodshed on the northern frontier had been too much for the Empire.

The defeat was so catastrophic that it threatened the survival of Rome itself, halted the Empire’s conquest of Germany and set the course of history for Central Europe.

Just imagine the alternative: If the Romans had won, the Anglo-Saxons, being subdued, would have learned Latin and might not have gone to England a few hundred years later??

And imagine even further that descendents of those Anglo-Saxons turned up in 1607 AD in Jamestown to lay down the foundations for man’s most modern civilization.

The Campaign of the Roman Leader Germanicus against Germanic Tribes

14 A.D. until 16. A.D. – and the Roman Limes

(fig.: #9)

The Saxons in Westphalia

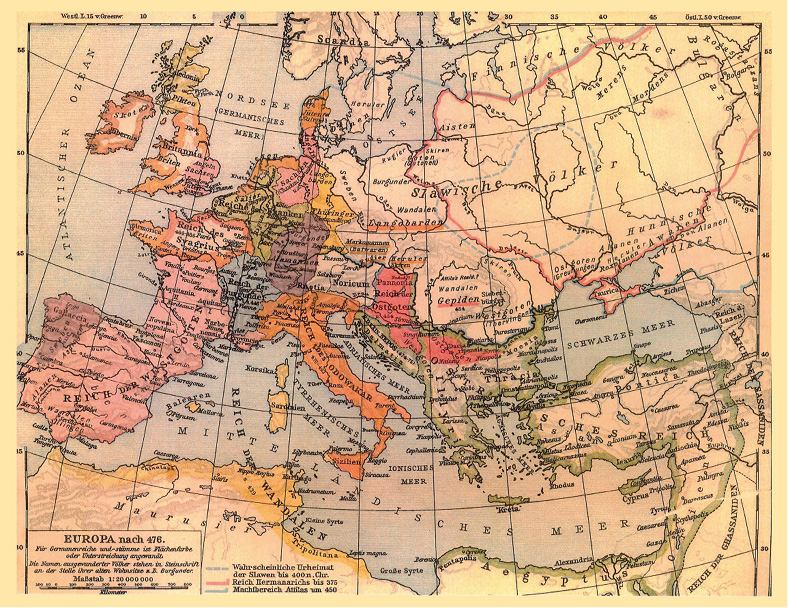

It is historically proven, that a little later the Germanic tribe of the Saxons settled in our area, covering all the territory of Westphalia, Engern and Holland.

Europe during the Migration of Nations ( around 500A.D.)

(fig.:#10)

The line of Saxonian noblemen goes back to Arminius, and the most important ones thereafter came from the house of Engern. This clan with Count Bodo ruled over all the Saxons. His son Wichten, and in turn, his son Wichtigis also became dukes of the Saxons.

Around 450 A.D. Count Hengist from the same dynasty together with Prince Horsa founded a Saxonian king-dom in England and called themselves kings. At that time the English county of Herfordia got her name from a borough of Herford not far from Enger. Count Hengist is also the reason for many English lord-titles, like Elting, Lindhorst, Bathorst, Herbert and others, all going back to actual Westphalian farm places.

These same two Saxonian noblemen from Westphalia, Hengist and Horsa, should come up again 1315 years later during the preliminary discussions on the American Constitution:

A group of the Founding Fathers (Adams, Franklin, Jefferson) had a concept for the official Seal of the United States: Showing reference to the Common Law of the Anglo-Saxons on one side, represented by the Saxonian noblemen Hengist and Horsa, and on the other side, the idea of God’s Law of ancient Israel.

The original concept proposal, however, was never realized.

Several attempts have been made over time to figure out what this proposal could have looked like. One such an idea as shown in the National Center for Constitutional Studies is shown in a sketch on the following page.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire, and after Constantin III, the Roman military commander in England, withdrew his legions, England got visitors from the continent. Three Germanic tribes, the Saxons, the Jutes, and the Angles stormed part of the island. The original Celtic people didn’t have a chance. Battle after battle was lost; till only poetic revenge was left (legend of King Artus).

Around 600 AD, there were seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in England. One of those kingdoms was in Essex un-der the rule of King Sebert, the centre of the Saxons around London.

Most recent excavations in Essex (= East-Saxons) near Sutton-Hoo as well as in Cumwhitton near Carlisle provi-ded proof of early Germanic graves of that period. The findings in Sutton-Hoo could relate to King Sebert, who died 616 A.D., after he had converted to Christianity in 604 AD. This “royal tomb” of Sutton Hoo shows a typical set-up of the old pagan belief of the Saxons even when the corpse carried some Christians symbols.

Helmet from the Sutton Hoo ship-burial 1, England.

British Museum [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)]

Hengist’s son Hadugast, his successor, remained in Saxony and his son Hulderich (also known under the name of Childerich), born 584 AD, fought and protected for the first time the Saxonian territories against the power-ful, aspiring Franconians, another Germanic tribe. This conflict should prove fateful to the Saxons over the next centuries.

Around 630 AD, Hulderich’s son Sieghart (also known as Sigismund) reigned over the Saxons.

His son Dietrich, in skirmishes with the Franconians, now led by Karl Martell, was captivated and imprisoned.

Karl Martell (688 – 741AD), nicknamed the “Hammer”, son of Pipin II, was mayor of the Franconian palace. He managed to bring earlier domains of the Franconian kingdom under his control and fought the aggressive Mos-lems at Tour, pushing eastward towards various Germanic tribes.

Under him, the two principal elements of feudalism, the fief and vassalage developed, and the historic alli-ance between the Frankonian Kingdom and the Papacy began.

While Dietrich was in captivity, his wife, a duchess from the Wendish country, had two sons:

King Edelgard and Duke Warnekin. Edelgard died 753 A.D. in a battle with Pipin the Short, who is the father of Charles the Great (Charlemagne).

After this battle, Pipin the Short was the first to march into the heartland of the Saxons, all the way to the fortified castle of Rehme, located direct on the Weser River.

The Long Struggle between the Saxons and the Franks

(The land of our ancestors)

Warnekin, after succeeding his brother as king of the Saxons, had two children (sons) with his wife Kunhilde, a princess from the island of Ruegen: -- Wittekind (also known as Wedekind) and Bruno.

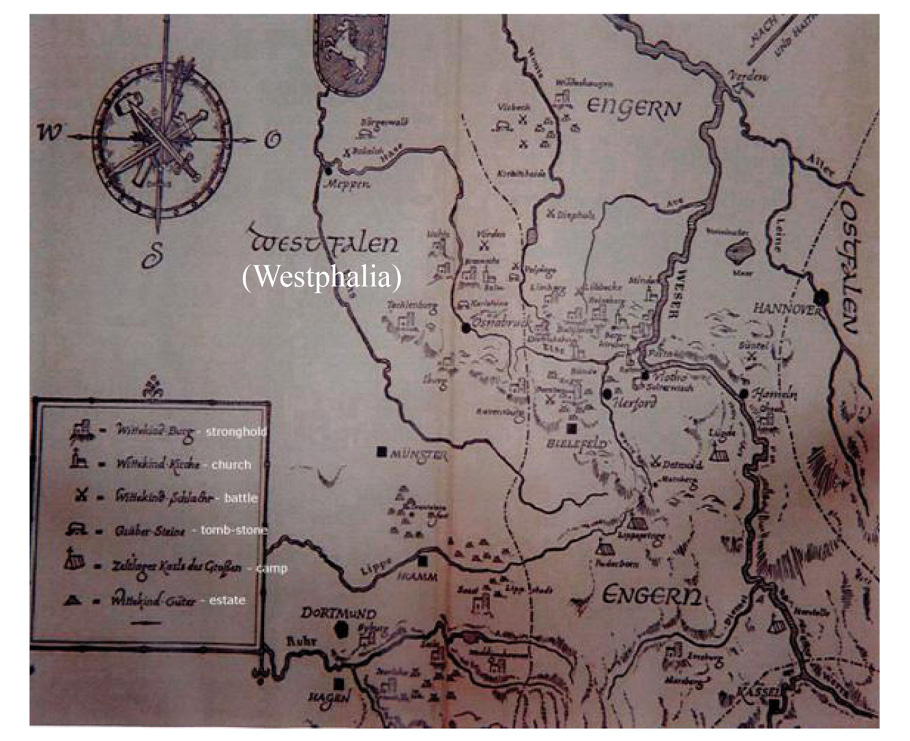

In 758 AD Wittekind became Duke of Engern, Westphalia, and Saxony.

He spent his childhood between Warnekin`s court at the mountain stronghold “Babilonie” in the Wiehengebirge between Herford and Osnabrück and the ancestral castle in Wigaldishausen (=Wildeshausen) on the Hunte River.

His dukedom, the free land of the Saxons, extended from the Lower-Rhine-Valley eastward to the Weser River and all the way to the Wendish (Slavic) territory in the East. (fig.:#11)

While Wittekind lived according to the old customs of his ancestors, King Karl, at the same time, tried to spread Christianity. Later in history, King Karl was named “Charlemagne”.

And while the Saxons had built a number of fortified places (Soest, Iserlohn, Hohensyburg, Seiler, Arnsberg, Eresburg, etc.) against the pressing Franks, King Karl, at the same time, gathered his “Royal-Court” in Worms and proclaimed war against the Saxons.

The Franconian records report a statement from King Karl: “First the castles and then the hearts”.

Saxon versus Franks around 800 AD

Some details of the 30 year long struggle are shown in the graph below: (fig.:#11)

A “stronghold” is a fortified place at the time = bulwark on hills surrounded by stockades and walls of soil and woodwork. (fig.:#11)

Why these details?

Because the conflict between Wittekind and King Charles (Charlemagne), resulted finally in the bloody subjuga-tion of the Saxons and was another major turning point in the history of our area.

The map of fig.:#11 shows a number of fortified places which the Saxons used in their struggle against their neighbours in later years, especially against the Franconians, another Germanic tribe.

The thrust of the Franconian army was pushing alongside the Weser River towards the heart of the Engern people, one of the four tribes of the Saxons. This expedition left a trail of devastation behind: Farms and grain fields went up in flame. There was robbing, and looting, etc.

As always in the long history of mankind: the farmers took most the brunt of the harm.

The story of this conflict is mostly based upon two sources: the Franconian narrative (some in writing), and the abundant information included in the Saxon version, passed on through generations and kept alive in numerous legends.

Wittekind and Geva, a daughter of Godefried, the king of Denmark, had three daughters: Ida, Ravena, and Tekla. He built a fortified castle for each of them: Iburg for Ida, Ravensburg for Ravena and Tecklenburg for Tekla.

Those three castles protected the chain-mountains of the Teutoburger Wald against aggressors.

Iburg, as the saying goes, was the strongest foothold against the Franks. From here, Wittekind directed a series of assaults; and yet he could not hold the ground for long. As Iburg was lost, he moved to Ravensburg; and this stronghold was soon taken by the Franks as well. This made him move to Tecklenburg. Finally, King Karl overran Tecklenburg also, and he dismantled all three of them thoroughly.