Полная версия

File Under: 13 Suspicious Incidents

File Under: 13 Suspicious incidents

First published in Great Britain 2018

by Egmont UK Limited

The Yellow Building

1 Nicholas Road

London W11 4AN

Text copyright © 2018 Lemony Snicket

Art copyright © 2018 Seth

Illustrations published by arrangement with Little, Brown, and Company, New York, New York, USA. All rights reserved.

The moral rights of the author and artist have been asserted

First e-book edition 2018

Ebook ISBN 978 1 4052 7643 6

www.egmont.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Sub-file One: REPORTS.

INSIDE JOB.

PINCHED CREATURE.

RANSOM NOTE.

WALKIE-TALKIE.

BAD GANG.

SILVER SPOON.

VIOLENT BUTCHER.

TWELVE OR THIRTEEN.

MIDNIGHT DEMON.

THREE SUSPECTS.

VANISHED MESSAGE.

TROUBLESOME GHOST.

FIGURE IN FOG.

Sub-file B: CONCLUSIONS.

BLACK PAINT.

DEEP MINE.

DISHONEST SALESMAN.

BACKSEAT.

LOUD DOG.

QUIET STREET.

THROUGH THE WINDOW.

BENEATH THE STREET.

HOMEMADE FURNITURE.

SMALL COURTYARD.

TWENTY-FIVE GUESTS.

MISSING PETS.

SMALL SOUND.

LARGE MEAL.

CHALKED NAME.

OTHER NAME.

PANICKED FEET.

SAND AND SHORE.

VERY OBVIOUS.

POOR JOKE.

MESSAGE RECEIVED.

MESSAGE RECORDED.

TRAIN WRECK.

NERVOUS WRECK.

SHOUTED WORD.

LAST WORD.

Sub-file III: ALL THE WRONG QUESTIONS

Back series promotional page

ABOUT THE AUTHORS.

Please find enclosed herein thirteen (13) reports filed under “Suspicious Incidents” in our archives. The thirteen (13) reports have thirteen (13) conclusions which have been separated from their corresponding reports for security reasons. The reports are contained in sub-file One (1) and the conclusions in sub-file B (b) so that it is impossible for each report and conclusion to be in the same place at once. For your convenience, both sub-files are enclosed together in this bound volume.

The information contained herein is secret and important, meant only for members of our organization. If you are not a member of our organization, please put this down, as it is neither secret nor important and therefore will not interest you.

All misfiled information, by definition, is none of your business.

Sub-file One: REPORTS.

Inside Job. Pinched Creature. Ransom Note. Walkie-Talkie. Bad Gang. Silver Spoon. Violent Butcher. Twelve or Thirteen. Midnight Demon. Three Suspects. Vanished Message. Troublesome Ghost. Figure in Fog.

INSIDE JOB.

One morning I was arguing with the adult in charge of me. I’m sure I don’t have to tell you what that is like, and it is one of the world’s great difficulties that this sort of argument goes on nearly every place on almost every morning between practically every child and some adult or other. Another one of the world’s great difficulties was S. Theodora Markson. During my time in Stain’d-by-the-Sea, Theodora was my chaperone and I was her apprentice. Being her apprentice meant that we shared a small room in a hotel called the Lost Arms. The room was too small to share with one of the world’s great difficulties, and this was probably why we were arguing.

“Lemony Snicket,” she was saying to me, “tell me exactly what being an apprentice means.”

“S. Theodora Markson,” I said, “tell me exactly what the S stands for in your name.”

“Snide answers aren’t proper,” she said. “They’re not sensible.”

“I know it,” I said, and I did. “Snide” is a word which here means “the kind of tone you use in an argument,” and “sensible” refers to the tone you are supposed to use instead.

“If you’re smart enough to know that,” Theodora said, snidely, “then tell me all about being an apprentice.”

“You and I are in a secret organization,” I began, but Theodora looked wildly around the room and shook her head at me. My chaperone’s hair was a crazed and woolly mess, so when she looked around the room and shook her head, it was like seeing something go wrong at a mop factory.

“Shush!” she hissed.

“Why shush?”

“You know why shush. You shouldn’t talk about our secret organization. You shouldn’t even say the words ‘secret organization’ out loud.”

“You’ve just said them twice.”

“It doesn’t count if I say it in order to tell you not to say it.”

“Well, what can I say instead?”

“You know what.”

“No, I don’t know what,” I said. “That’s why I asked you.”

“Say ‘you know what,’ ” Theodora said, “instead of ‘secret organization.’ That way you won’t have to say ‘secret organization’ out loud, which you should never do.”

“Except in order to tell me not to say it,” I reminded her, and went on with my answer. “You and I are in you know what, and being your apprentice means I’m learning all the methods and techniques used by you know what. There are sinister plots afoot in this town, and you and I should be working together to defeat them in the name of you know what.”

“Wrong,” Theodora said, with a stern hair-shake. “Being my apprentice means you do everything I say.”

“That’s not what I was told,” I said.

“Who told you?”

“You know who,” I said, just to be safe, “at you know what, you know where, when, and how.”

“You’re talking nonsense,” Theodora said. “Breakfast is ready. As your chaperone, I’m telling you to hand me two napkins.”

“As your apprentice,” I said, “I’m telling you we don’t have any.”

“I suppose it doesn’t matter,” Theodora said, and I suppose she was right. My chaperone made us breakfast every morning on a metal plate provided by the Lost Arms. When you flicked a switch the plate got hot, and this morning Theodora had laid two slices of bread on it and then begun arguing with me. Now the bread was burned black on one side, like a shingle covered in tar, and the other side was soft and cold from sitting on the windowsill we used as a refrigerator. A napkin would not turn a half-burned, half-cold piece of bread into breakfast. A garbage bin would have been more helpful. I put the failed toast in my mouth anyway. Theodora didn’t think it was proper for her apprentice to talk with his mouth full, so it was the best way to avoid talking to her.

Over the sound of burned crusts against my teeth I heard a knock on the door, and Prosper Lost peeked in at us. He was the Lost Arms’ proprietor, a word which here means he stood around the lobby with a small smile and called it running the place. I called it a little creepy, although not to his face. “Lemony Snicket,” he said.

“You’re not Lemony Snicket,” Theodora said to him.

“There’s someone downstairs to see you,” Lost explained to me.

Theodora frowned at the proprietor. “Whoever’s waiting downstairs isn’t Lemony Snicket either,” she said. “Lemony Snicket is right here with crumbs on his shirt.”

“Someone is here to see Lemony Snicket,” Prosper Lost said, as clearly as he could.

“Thank you,” I told the proprietor, and excused myself.

“Whatever you’re doing,” Theodora called after me, “be quick about it. You have a very busy day, Snicket. You have to buy some napkins.”

My mouth wasn’t full, but I pretended it was so I didn’t have to answer as Prosper Lost led me down the stairs. “Who is it who wants to see me?” I asked him.

“A minor,” Lost replied.

“Do you mean a child, or someone who works in a mine?”

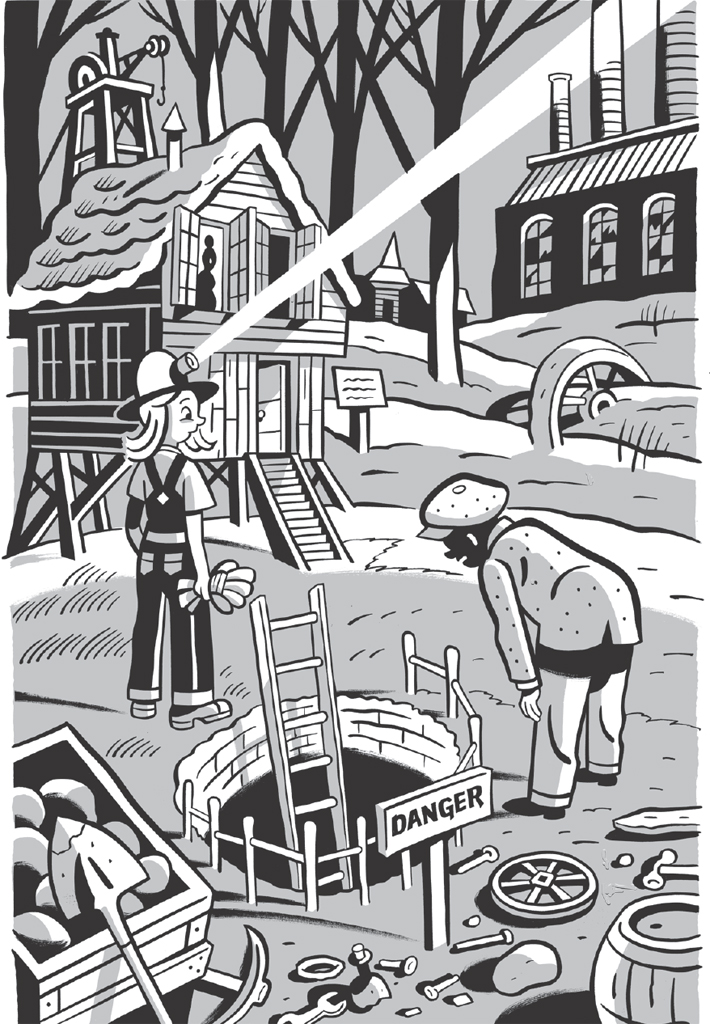

“Both,” Lost said, and sure enough, in the lobby was a girl about my age wearing a helmet with a light attached to it, the kind people wear when digging underground. The hat looked a little big on her head, and she took off some oversized work gloves so she could shake my hand.

“I’m Marguerite Gracq,” she said. “I spell it in the French way.”

“I’m Lemony Snicket,” I said. “I think my name is spelled the same in any language.”

“Around town they say you’re something of a detective.”

“Around town they’re wrong. I’m something else.”

“Well, I need some help.”

“What kind of help?”

“Pictures are falling down in my living room.”

“Sounds like you need a handyman.”

Marguerite shook her head. “They’re falling too neatly.”

“Maybe it’s just because I’ve had a lousy breakfast,” I told her, “but I’m not following you.”

“Follow me to my home,” Marguerite said, “and I’ll explain everything and poach you an egg, besides. I put a little vinegar in the poaching water, so my eggs turn out nice and fluffy.”

A fluffy poached egg is a good breakfast, and a good breakfast is better than a bad one, like a good book is better than having your toe chopped off. We walked out of the Lost Arms together and down the quiet street. Most of the streets in Stain’d-by-the-Sea were quiet. The town was emptying out.

“I know that most businesses in town have been failing,” I told Marguerite, with a nod at a boarded-up shop. “How’s mining going?”

“There’s just one small mine in Stain’d-by-the-Sea,” she said, “and it’s in my front yard. My father says we’ve gotten all the gold we’re going to get from it. He’s out of town for a few weeks finding us a better place to live. I’m staying here to close up the mine and make sure nothing happens to the gold.”

“He left you here all alone?”

Marguerite frowned and shook her head. “He hired a woman named Dagmar to watch over me. She doesn’t do much but sit and listen to the radio. I don’t like her.”

“What does she listen to?”

“Polkas.”

“No wonder you don’t like her.”

Marguerite smiled. “That’s not the only reason,” she said. “Dagmar doesn’t seem trustworthy. The paintings didn’t start falling until she arrived, and nobody else has been around. I keep thinking she’s after something, but nothing has been stolen.”

“Most untrustworthy people hanging around a gold mine are after the gold.”

“My father has been very careful about his stash,” she said. “When we bring gold up from the mine, he immediately takes it all to his workshop to melt it down. Then he hides it someplace in that room. Even I don’t know exactly where, and I have the only workshop key. My father gave it to me when he left town, and I keep it with me always.”

Marguerite reached into her overalls and drew out a skinny key on a thick cord around her neck.

“Have you ever let Dagmar use the key?” I asked. “She could have had a copy made.”

Marguerite shook her head. “I’m the only one who’s been in the workshop since my father left, and I can see that nothing has been touched. The problem’s not with the gold, Snicket. It’s with the pictures in my living room.”

We’d arrived at a small wooden house with a roof covered in moss, narrow windows wide open, and a large hole in the front yard with the top of a ladder jutting out from it. Various tools were scattered around the browning lawn. From the windows I could hear a particularly peppy polka. All polka music is peppy. There’s nothing wrong with feeling peppy, but a polka insists that everyone else has to be peppy too, even if they don’t feel like it.

Marguerite kicked off her boots and led me into a friendly-looking place. There was a large wooden staircase with piles of books here and there, and a carpet decorated with images of mythical beasts and smudges of dirt. Leafy plants hung in the windows, shedding leaves wherever I looked.

“I’m back, Dagmar,” Marguerite called upstairs. “I have a friend with me! I’m going to make him a poached egg!”

“Do whatever you want,” replied a cranky voice, over the sound of the polka. The music’s peppiness had clearly not spread to Dagmar.

“The kitchen’s right over here,” Marguerite said, “but if you don’t mind, I’d like to show you the living room first.”

“Of course,” I said, and she led me through an archway into a room as pleasant and rumpled as the rest of the house. The wooden floor was painted black, with the paint peeling off here and there, and the sofas and chairs were all bright yellow except where they were patched up with squares of other bright fabrics. There was a large reading lamp, made from another miner’s helmet, and on the walls were portraits of pale, thoughtful-looking people, with one portrait leaning against the wall underneath a blank space on the wall where it clearly belonged. One portrait, depicting a man with a bow tie and an elegant cane, had a large rip right across the middle, and Marguerite looked at it sadly. “Henry Parland was the first one to fall,” she said, “just a few minutes after Dagmar arrived. Luckily, it’s the only one that’s been damaged. Since then, it seems that one falls whenever I’m down in the mine. Paavo Cajander, Katri Vala, Eino Leino, Otto Manninen, and this morning Larin Paraske, who had already fallen, was found right as you see her, leaning on the wall like all the others.”

“Your father certainly likes Finnish poets,” I said.

“These portraits belonged to my mother,” Marguerite said. “They were precious to her, but they’re not particularly valuable.”

“And they haven’t particularly been taken,” I said.

“Nothing has,” Marguerite said, looking around the room. “I admit I’m suspicious of Dagmar, but I can’t say she’s committed any kind of crime. The paintings just keep falling and then we hang them back up.”

“You say they fall when you’re in the mine,” I said, glancing out the window at the hole in the yard, “but surely you can’t hear them fall from down there.”

“Dagmar tells me they’ve fallen,” Marguerite said, “or I notice myself when I come in for a snack.”

“And who puts them back up?”

“I do,” Marguerite said, with a note of pride in her voice. “I fetch a hammer and a nail from the workshop and do the job myself. And I do it right, Snicket. Don’t think it’s my fault they keep falling.”

“Maybe the first one fell,” I said, with a glance at the rip in Henry Parland, “but if the others were found leaning against the wall like this, they probably didn’t fall.”

“That’s how they were,” Marguerite said with a nod. “Leaning against the wall, nice and neat, with nothing damaged.”

“Do you leave the workshop door open while you rehang them?”

Marguerite gave me a sharp look. “Of course not. The gold is somewhere in that room, and it’s my responsibility to keep it locked up.”

I turned my eyes from the girl to Larin Paraske. The poet in the portrait looked back at me but offered nothing more than a thoughtful gaze and an unusual hat. I tilted the portrait and looked behind it at the cord stretched across so the painting would hang evenly from the nail. I looked at the blank space on the wall, and at the tiny hole in the dark wood. “Do you have a lot of nails in the workshop?” I asked.

“Jars and jars full,” Marguerite said. “My father uses these special black nails all around the house. They curve slightly, so they do less damage to the wall.”

“And what about the hammer?”

“It’s an ordinary enough hammer,” Marguerite said. “Do you want to see it?”

“I don’t need to,” I said. “I’m going upstairs to talk to Dagmar.”

“What are you going to ask her?”

“First,” I said, “I’ll ask her to turn off that blasted polka music. And then I’ll demand that she return all she’s stolen from your family, before we hand her over to the police.”

* * *

The conclusion to “Inside Job” is filed under “Black Paint,” here.

PINCHED CREATURE.

I was spending the afternoon with my associate Moxie Mallahan. Moxie was Stain’d-by-the-Sea’s only reporter, a job she had learned from her parents, who had run the town’s newspaper, The Stain’d Lighthouse. The newspaper was shut down, Mrs Mallahan had left town, Mr Mallahan was sleeping late, and Moxie and I were just hanging around the lighthouse, doing a little reading and talking over various incidents that had happened recently. “It’s been too long since we’ve done this,” Moxie said.

“Done what?”

“Had an uneventful time like this.”

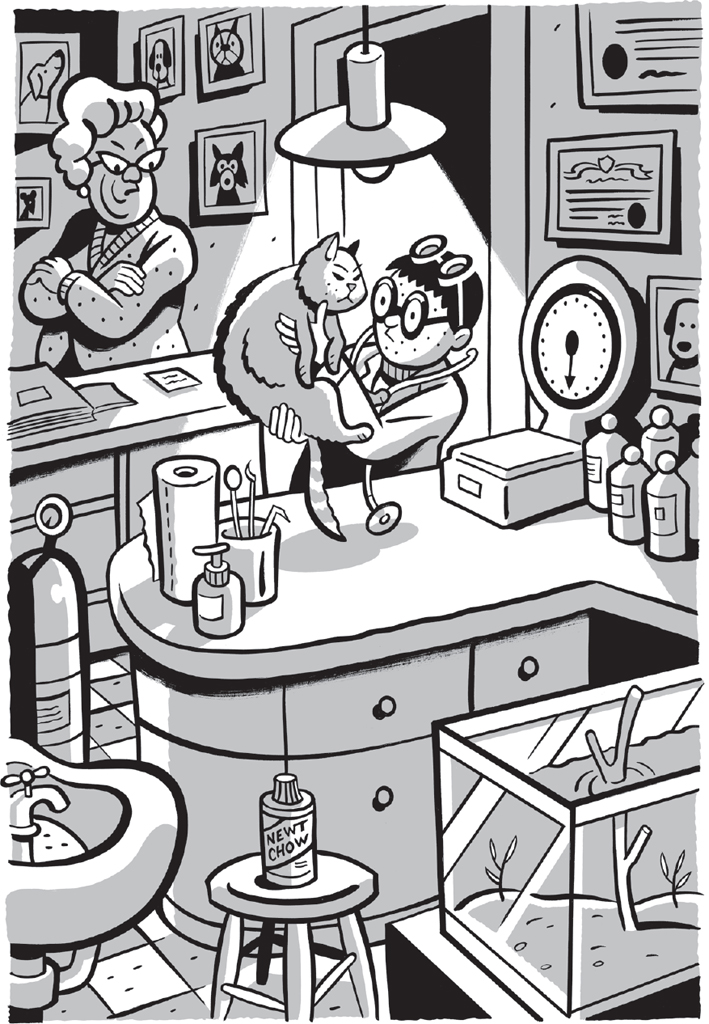

Right on cue, the doorbell rang, as if to say enough was enough of uneventfulness, and when Moxie opened the door, there was an event. The event was a boy several years younger than I was and much more upset. He wore a white coat like a scientist and had two pairs of glasses, one over his eyes and the other perched on his head.

“I’m sorry to disturb you,” the boy said, “but you’re the closest neighbor and I need some help.”

“Oliver,” Moxie said. “I didn’t know your family was still in town.” She turned to me. “Oliver’s parents are the only veterinarians left in Stain’d-by-the-Sea. So few people have pets nowadays, I’d assumed the Doctors Sobol had closed up shop.”

“They have,” Oliver said, his eyes blinking nervously behind his glasses, “but I’m here for a few more months running the business until they come and fetch me.”

“Well, if you ever want company,” Moxie said, “hike up the hill and we’ll play some Parcheesi. This is my friend Lemony Snicket, by the way. He won’t play Parcheesi because he says it’s inane.”

“It is inane,” I said, “and inane is a word which here means pointless and dull.”

Oliver frowned, and I can’t say I blame him. If you are worried about something, it is not a good time to listen to people argue over games and vocabulary. He sat down glumly at the bottom of the stairs that spiraled up to the lighthouse’s lantern.

“I’m sorry, Oliver,” Moxie said. “We were prattling on while you have something on your mind.”

“I sure do,” Oliver said. “I’ve lost a newt.”

Moxie and I both looked at Oliver. If we’d looked at each other we might have laughed.

“It might sound silly,” Oliver said, “but this newt is very important.”

Moxie’s eyebrows went up underneath her hat. “What could be so important about a little lizard?”

“First of all,” Oliver said, “newts aren’t lizards. A lizard is a reptile, and a newt is an amphibian. Second of all, this newt is a very rare subspecies. I’ve lost an Amaranthine Newt, known for its bright yellow color and prevalent left-handedness. It was the only one in captivity and prized by herpetologists and southpaws all over the world.”

“Why do they call it the Amaranthine Newt, if it’s bright yellow?” I asked. “Amaranthine means purple, doesn’t it?”

“Its eggs are purple,” Oliver said. “My father took the eggs with him to his new job at Amphibians-A-Go-Go, an aquatic animal center and amusement park just outside the city. The newt and I are supposed to join them there soon. If I can’t find the newt, my father might lose his job.”

“Don’t fret, Oliver,” Moxie said, although I could see that Oliver just kept on fretting. “Snicket here has a knack for finding strange missing items. Isn’t that so, Snicket?”

“It’s sometimes so,” I said. “Oliver, why don’t you tell us how the newt slipped away?”

“I don’t think it slipped away,” Oliver said. “I think it was pinched.”

“Somebody stole it?” Moxie said. “That’s a serious accusation to make.” She sat down and opened a case sitting on the floor. Inside was a typewriter that Moxie Mallahan always kept nearby, and she started taking notes immediately on the clattering machine.

“I’m making it seriously,” Oliver said. “The Amaranthine Newt lives in a special tank on a desk in my examining room, so I can always keep an eye on it. It was there when I opened for business this morning.”

“And how many patients did you have today?” I asked.

“Just one,” Oliver said. “You were right about few people having pets, Moxie, but Polly Partial has two of the last cats in town, and one of them has a narcissistic disorder.”

“Polly Partial, the grocer?” Moxie asked, and met my eye. Neither of us was fond of the woman who ran Partial Foods, but lots of people nobody is fond of have sick cats.

“Her cat Paperbag has been a patient of my family’s for a very long time,” Oliver said. “I can’t imagine that his owner is a thief, but greed and newts can do strange things to people. I examined Paperbag and went to my desk to write out a prescription. Then I escorted Partial and Paperbag out and spent a few minutes in the backyard watering my father’s zinnias. The flowers match the trim on the office, as long as you keep them healthy, and I’d like to leave the place looking nice. When I went back into the office, the tank was empty.”

“Someone must have snuck in while you were gardening,” Moxie said.

Oliver shook his head. “I would have heard anyone else driving up the road.”

“They need not have arrived by automobile,” I said.

“To pinch my newt,” Oliver said, “they’d need a similar tank. You couldn’t fit one on a bicycle or a donkey. Polly Partial must have stolen the newt, but I don’t see how.”

“I don’t mean to be rude,” I said, “but can you really trust your eyes? I notice you have not one but two pairs of glasses.”

Oliver gave me a stern, lens-covered look. “My eyes aren’t perfect,” he said, “but with these glasses I can see perfectly well, and I keep the other pair on my head for reading.”

“You don’t have bifocals?” I asked, referring to eyeglasses that combine two lenses into one.

“There aren’t any optometrists left in town,” Moxie told me. “The closest eye doctor is way over in Paltryville, but she doesn’t have a very good reputation.”

“Did you use your reading glasses when you were with Paperbag?” I asked Oliver.

He nodded. “When I wrote out the prescription.”

“Well, I’m sure you saw clearly,” I said, “but I’m not sure I do. Shall we walk over to the Sobol office?”

Oliver said yes and so we did, Moxie carrying her typewriter and me trying to think. It was a warm, breezy day, with the wind carrying a salty smell from the seaweed of the Clusterous Forest, an eerie phenomenon that lay below the cliff we were on. But we walked the other way, down a road as bumpy and cracked as a vase falling down stairs. Soon enough, we could see the office of the Doctors Sobol, a faraway building with yellow and orange trim, but when we rounded a corner, something made us stop. There was a car, pulled over to the side of the road, and a man frowning at the car like it’d given him socks for his birthday.