Полная версия

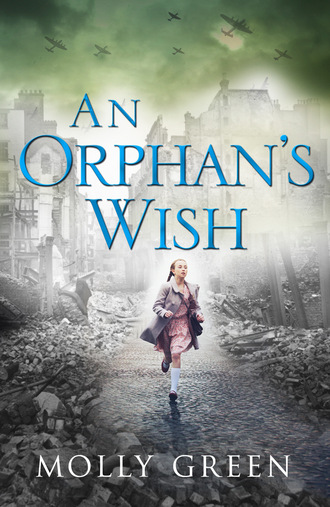

An Orphan’s Wish

There was a deathly hush. And then a loud scraping of a chair by the window. Before she had time to stop her, Priscilla had sprung up, grabbed her satchel and rushed out of the room.

‘I hope you’re satisfied now, Josephine,’ Lana said. ‘You will stay behind and explain yourself before you do your lines.’ She threw a glance around the room. ‘We’re finished for the day, children. You may go.’ She waited until the children had disappeared and only Josephine was left, standing sulkily beside the desk.

‘Sit down in one of the front seats,’ Lana said, taking her chair and moving it nearer to Josephine. It was easier not having a desk as a barrier between them, she thought.

‘Now, then. What made you speak in such an unkind way about another pupil?’

Josephine sniffed.

‘Have you a handkerchief?’

‘No, Miss.’

Lana dug in her bag and handed the girl a neatly folded one. She waited patiently. ‘Well, Josephine?’

‘No one likes Prissy, only no one’s brave enough to say it ’cept me.’

‘You mean Priscilla?’

‘We all call her Prissy because she’s such a fusspot. She tidies her desk after every lesson. We all know she’s stupid because she’s always bottom.’

‘No, she’s not stupid. She’s just a very sad little girl. And she needs help. I think you might be just the person.’

‘What do you mean? I don’t even like her.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because she thinks she’s better than us so she doesn’t speak to us. So we do the same.’

‘It’s not that at all,’ Lana said. ‘It’s because she’s embarrassed and angry with herself.’

‘Because she’s stupid.’

‘Don’t say that word again, please,’ Lana said sharply. ‘She’s not stupid.’ She looked at the girl. ‘Do you have a mother and father, Josephine?’

‘Course I do.’

‘Then you’re very lucky. One day Priscilla had her own bedroom at home and a loving mother and father. The next she was told they’d been killed in the blackout and she had to go and live at the orphanage down the road. It’s extremely difficult for her, and you and the others are making it worse by not speaking to her, or including her in your games. I want this to change.’ All this time Lana kept her focus on Josephine who looked shocked and upset at the same time. ‘Can you understand what I’m saying, Josephine?’

The girl hung her head.

‘Josephine?’

Josephine looked up, her eyes flashing. For a moment Lana thought she was going to rebel against her.

‘I didn’t know, Miss, about her mother and father.’

‘There’s a war on, Josephine,’ Lana said gently. ‘Anything can happen at any time to those we love. Do you think you can be kinder to her?’

Josephine nodded.

‘And Priscilla’s far from stupid. She’s a clever girl and I’m sure she would help you with your homework if you got stuck – especially your reading. Then maybe you can put your hand up for a part next time.’

Josephine’s face visibly brightened.

‘In the meantime,’ Lana continued, ‘tell her you will be her friend. Try to understand how she feels. Imagine it had happened to you and you’d lost your parents. You’d want to have a friend to talk to, wouldn’t you?’ Josephine nodded, keeping her eyes averted. ‘And the first way to show her you mean it is to tell her you’re very sorry for speaking the way you did.’

There was a silence. Lana could almost see Josephine weighing everything up. Finally, she said, ‘All right, Miss Ashwin. I’ll tell her I’m sorry.’

‘Just one more thing, Josephine. We’ll forget about writing out my name fifty times, but I’d like you to stand up in class tomorrow morning and tell the children what happened to Priscilla. I’ll make sure she’s not there. But tell them they must not mention it to her afterwards. She’d hate that. Just ask the others to include her – make friends with her. And above all, be kind.’ She paused to give time for her words to sink in. ‘What do you think?’

Josephine was looking at the floor. ‘I’ll do my best, Miss Ashwin,’ she muttered.

‘Your best is exactly what I’m looking for,’ Lana said softly.

Chapter Ten

Josephine carried out Lana’s instructions but it only resolved the problem in that particular class. Lana could see Priscilla’s mouth set as she went from one lesson to the next, not turning her head to look at anyone.

When Lana spoke to Janice about it one evening she realised the teacher hadn’t changed her mind at all.

‘Of course I won’t tolerate rudeness,’ Janice said, ‘but I just think we must give it time.’

‘I disagree,’ Lana said. ‘If we don’t come out in the open so Priscilla knows we all know and can feel our concern, I can’t see how she’s ever going to overcome this tragedy.’

‘Children are quite resilient,’ Janice said. ‘Priscilla’s quite strong underneath.’

‘Let’s hope so.’ She looked at Janice. ‘Oh, I had a telephone call from Mrs Taylor, the matron at the orphanage. She’s invited our children to join in with their May Day celebrations. They’re having a maypole and it sounded fun.’

‘It’s the first time we’ve been invited,’ Janice said, sounding surprised. ‘I suppose it’s because they had that awful matron who hated everyone. But they sacked her and employed a much younger one a while ago. I was told she’s having a baby so this Mrs Taylor must be taking over.’

‘She sounded awfully nice,’ Lana ventured. ‘What do you think?’

‘You’ll find most of the children will be at home with their families as it’s a Saturday,’ Janice said. ‘And I can’t see Wendy – or me, come to that – wanting to spend the day at Bingham Hall on our day off. One of us would have to be there to supervise our kids. And I’m not sure it’s a good idea anyway, suddenly mixing the two lots of children. It would be far better to let the orphans have their celebration on their own without any added strain of strange children they’re forced to play games with, particularly when it’s on their special day.’

‘You’re probably right,’ Lana said. ‘I didn’t think of it that way.’

In bed that night Lana mulled over what Janice had said. She had to admit there was a good deal of sense in it, yet she still felt it was a good idea to get both sets of children talking to one another, that it was more natural than to keep them separated all day, every day. But there was no harm in her wandering over to Bingham Hall on May Day. It would give her the chance to see how Priscilla was faring at the weekends. She would form a better picture of the child, and maybe Mrs Taylor might have some suggestions as to how to help the young girl.

Lana changed her mind once or twice as to whether she should venture over to Dr Barnardo’s on May Day. It would look strange turning up with no children in tow. She decided to write Maxine Taylor a letter explaining some of her concerns but that she’d be pleased to meet her if it was convenient on that day.

She received an answer two days later.

Dear Miss Ashwin,

Thank you for your letter and I perfectly understand. You may well be right about mixing the children together on May Day. Perhaps some other time when we have a concert or a play and we can invite some of the children from the school to be part of the audience.

That said, I would be delighted to meet you. As you said, it could be useful where Priscilla Morgan is concerned. So why don’t you wander over on May Day and see us in the afternoon, say 4 p.m. We should be packing up by then and more than ready for a tea break!

If it’s not convenient, give me a ring during the week and we’ll make a firm arrangement. No need to reply. We’ll see you when we see you.

Yours sincerely,

Maxine Taylor (Matron)

Chapter Eleven

Lana opened her bedroom curtains to a dull, drizzling first day of May. Not the best weather for dancing round the maypole. She quickly got ready and dressed in a dark pleated skirt and cream twinset. Gazing at her reflexion she wondered if it was too severe for a walk over to the orphanage to introduce herself to Maxine Taylor. The skirt swung around her knees as she turned this way and then the other. Oh, dear. She wasn’t sure. Did it make her look old before her time? With the rationing, her wardrobe was limited to clothes appropriate for a teacher, together with a couple of summer frocks and a Sunday best outfit. She shrugged. Most women were in the same boat.

She spent the morning marking children’s compositions, noting that Priscilla’s was a couple of pages of short, jerky sentences, with an occasional description of sudden brilliance. She was a child worth nurturing back to her full potential, Lana decided. She made herself a sandwich in the cottage, unusually quiet since Janice had gone to see her aunt for a couple of days. It was heaven to have the place to herself. She wouldn’t stay at the orphanage for long this afternoon. Time on her own was too precious and she wanted to make the most of every minute. Janice would be back tomorrow evening ready for school again on Monday, and then there’d be no more peace.

She sat and read a few chapters of her book, then looked at the clock. Quarter past three. Much too early. But she could start slowly walking, maybe having a wander round the gardens – see how Priscilla was getting on. It would be good to get some air. She rose to her feet and washed her cup and saucer, then collected her raincoat from the peg in the hall.

Lana enjoyed walking along the country lane admiring the trees now in leaf. In spite of the dull sky her heart lifted because she was actually here, beginning her new life. Yes, it was without Dickie, but she knew she’d be doing something important for the future – making sure the children were continuing their education no matter what Jerry threw at them. Dickie would have approved.

She came to a small neat sign: Bingham Hall. The orphanage.

Strolling up the drive, she passed a cottage on the left, which looked as though it was going through some major repairs, and a little further on she saw several tall chimneys cutting through the clouds. She blinked. Built of red brick the house had a turret to one side and a crenellated front, reminding her of a castle. She had to admit it was an imposing house – well, more of a mansion – probably built in early Victorian times, the same as the village school.

What would it be like to work there? Grim, she supposed. All those children, some of whose parents had probably been killed in the war, thrown together with no blood ties, maybe losing brothers and sisters as well. Lana was suddenly grateful to teach at a normal school. An orphanage could never represent ‘home’ to her.

She could hear an accordion playing and smiled. The children were obviously not letting the dreary rain put a dampener on their day. Screams of laughter became louder as she got nearer.

Another sound. The purr of an expensive-sounding engine behind her. She pressed her back into one of the lime trees to give room to a large black motorcar. It was moving slowly, crackling the gravel. Out of habit, as it drew parallel, she glanced inside. She was vaguely aware of two men in the back seat, but it was the blond-haired man in the front passenger seat, masking the driver, that caught her gaze. He was only a few feet away and she couldn’t help looking at him. His eyes were fixed firmly ahead, his profile rigid. But she was struck by the power of his features: the well-shaped nose, the firm set of his jaw, and what she could see of his solemn mouth.

As though he felt her eyes upon him he turned to his left, and for long seconds he looked directly at her. Through her. His eyes were deep-set and she thought they were blue but she couldn’t be sure. A quiver ran along her spine. It was as though there was no rain-spotted window forming a barrier between them. He was more handsome than any man had a right to be. Telling herself not to be so silly, but more than a little embarrassed, she swung her gaze from his and fixed her eyes on the rear of the car. Yes, she was right. It was a Rolls. Her brothers hadn’t wasted their time teaching her to recognise all the makes and models for nothing. Oh, what she would give to be behind its wheel. But what was a top-class motorcar like that doing at an orphanage?

She shrugged. It was none of her business. She saw the two men emerge from the back of the Rolls-Royce and walk towards the entrance of the house, leaving the driver and his front passenger in the car.

Who were these men arriving in such a grand car? More specifically, who was the blond man? He must be someone important to have his own driver. Maybe he was a local dignitary, yet he didn’t look like a local man. Ah, perhaps he was a Dr Barnardo’s inspector, though surely either position wouldn’t warrant a driver and a Rolls.

Two young women appeared at the front door of the orphanage, the taller woman wearing a smart navy dress. Lana wondered if she might be Maxine Taylor. One of the men said something and the taller woman answered but Lana was too far away to hear the words. The man loped off and in the space of two minutes returned with the front passenger.

The blond man was exceptionally tall, even by her standards, and unusually he was hatless. The sun, out for the first time that day, glinted on his hair. He looked like someone in command with his confident stride. He glanced once towards the children dancing round the maypole. The accompanying man almost had to run to keep up. It would have been amusing at any other time, but there was something unnerving in the scene unfolding in front of her. After several moments the two women and three men disappeared into the house.

Lana strolled over to where the children were playing, trying to shake off the image of the man who looked different from anyone around here, thinking she might ask where Priscilla was. She watched the children for a few minutes. They certainly looked well cared for, but their expressions wore a kind of resilience – she couldn’t quite explain it, but it was as though they’d had to face more than most children, which of course was true. Maybe she was being fanciful, but she didn’t think so.

Two of the boys were watching her with open curiosity.

‘Are you a new teacher, Miss?’ one of them piped up. He looked to be about nine or ten with ginger hair.

Lana smiled. ‘I’m the new headmistress at the village school. I’ve come to meet some of you and Matron.’

‘She’s gone inside,’ the other boy said. ‘Some men came in that motor.’ He pointed. ‘It’s a Rolls-Royce,’ he added, the awe in his voice unmistakable. ‘Isn’t it smashing?’

‘Yes, it certainly is a beauty,’ Lana said with feeling. One day she’d have her own car, though maybe not a Rolls to start with, she thought, smiling to herself.

‘I’m having one of them when I’m grown up,’ the ginger-haired boy said, a determined expression fixed on his freckled face.

‘I’m sure you will if you want it badly enough.’

He nodded.

‘Have you seen Priscilla?’

‘No. She’s too toffee-nosed to play with us.’

‘I’m sure she doesn’t mean to be,’ Lana said, surprised. ‘I think she’s shy.’

The boy grunted. ‘She was helping Cook last time I saw her.’ He and his friend shot her another look, then dashed off.

So long as Priscilla was well cared for, Lana thought, though it was a pity she hadn’t mixed with the others.

It was only a tentative arrangement to see Maxine Taylor at four o’clock, but already it was coming up to that time. The matron would be busy at the moment. She’d have to wait until the meeting, or whatever it was, was over and until then she’d wander round the gardens. No one seemed to be taking any notice as she walked over to the vegetable garden where the gardener had erected wigwams of beanpoles ready for planting runner beans. A boy, bent nearly in two, struggled with a tough-looking weed. A little brown dog watched the boy’s every move. The dog cocked his ear, then ran towards her, giving little whines of delight, his tail wagging excitedly. The boy stood up.

‘Freddie! Here, boy! Come here!’

Freddie stopped in his tracks and looked round, uncertain as to what he should do – welcome the newcomer or obey his master?

‘He’s all right,’ Lana called, swiftly closing the gap between them. ‘Good boy.’ She patted the dog’s silky head.

‘I have to keep watch on him,’ the boy said importantly. ‘He’s only allowed here if he behaves. He used to live here but he only comes to visit now.’

‘He’s just like most dogs when someone new comes along. He wants to be friends.’

The boy looked at her directly with very blue eyes. Lana took in a quick breath. There was something about him. As though she’d seen him before. But that was ridiculous. She didn’t know any of these children.

‘Well, I know Freddie’s name now, but I don’t know yours.’

The boy hesitated, and Lana had the feeling he didn’t want to answer. But finally he said, ‘Peter – Peter Best.’

‘That’s a good manly name.’ Lana smiled again, but the boy didn’t smile back.

He looked much too serious for a child who couldn’t be more than nine or ten years old. Dear oh dear, these children must all have the most awful stories to tell – the way they lost their parents. The very idea made her feel sick at heart.

‘I’ll leave you to the weeding,’ she said. ‘I do hope I’ll see you and Freddie again.’

Peter nodded but his expression was one of indifference.

Lana decided it would be better if she saw the matron at a quieter moment. But when she noticed a group of small girls playing ring-a-ring-o’roses on the lawn, and a dark-haired woman who she guessed was a teacher keeping an eye on them, she thought she’d wander over and say hello.

The woman turned her head at Lana’s approach.

‘Hello. I’m Lana Ashwin, the new headmistress at the village school.’ Lana extended her hand.

‘Dolores Honeywell. I’m fairly new here, too, and pleased to meet you.’ She smiled at Lana. ‘I saw you and wondered who you were.’

‘Mrs Taylor invited me over to meet some of the children,’ Lana said. ‘I was looking for Priscilla really.’

‘Well, there’s Matron.’ Miss Honeywell motioned towards the front door. ‘She’s with Mrs Andrews – or June, as she was known – who used to be the matron before she married, but I don’t know who that tall fair-haired man is.’ She paused. ‘Oh, he’s going over to the greenhouses. Wonder why. He doesn’t strike me as a gardener.’ Dolores Honeywell turned her attention back to the children.

Lana watched as the blond man walked slowly over to the vegetable plots where she’d left Peter and Freddie just a short while ago. She thought she heard someone whistling. From where she stood she couldn’t see the boy clearly, but she saw him standing very still, his back to the man. Then to her astonishment he whirled round and she heard him shout, ‘Papa!’ and hurl himself into the stranger’s arms.

Peter’s father?

The tall man held the boy tightly and kissed the top of his head. Lana couldn’t take her eyes off the two of them. Bingham Hall was an orphanage, yet it seemed as though Peter had unexpectedly been reunited with his father. She felt the tears prick and turned away, not wanting to encroach on their private moment.

This wasn’t at all the right time to speak to Maxine Taylor who’d probably had no idea at all that these gentlemen would be turning up when she’d suggested Lana go over to introduce herself around teatime. She’d leave quietly and telephone the matron in the morning to apologise and make a firm appointment next time.

She slipped amongst the trees lining the drive, the children’s shouts and squeals of laughter sounding far away now, and made her way back to the school, the image of the tall blond man gathering his son close to his chest still sharp in her mind. She wiped a tear away with the back of her hand and smiled to herself for being so sentimental, but somehow it was comforting to know that in this interminable cruel war, the scene that had unfolded in front of her looked as though it had all the elements of a happy ending.

But there was no happy ending for Priscilla, Lana thought sadly, as she turned the key to open the cottage door, imagining the young girl in her mind’s eye watching such a reunion.

Lana put the kettle on, feeling a little light-headed as she remembered the way the blond man’s eyes had held hers. Why had he made such an impact?

She drank her tea without tasting it.

Chapter Twelve

May Day – that night

‘Put the torch out!’ she hissed.

‘That’s no good. I can’t see a bleedin’ thing now.’ The youth switched the torch back on.

‘Well, put your hand over it.’

‘To hear you, you’d think Jerry was flyin’ overhead lookin’ down at us.’

‘You never know.’ The girl gave a nervous giggle.

The two of them crept up the drive, the gravel crackling underfoot at every step.

‘Go on, then, I dare you.’ She dug the youth in the ribs. ‘I’ll keep watch but they’ll all be asleep.’

The youth stretched his neck to assess the open window on the first floor of Bingham Hall. Then he twisted round to her. ‘Whadya bet?’

‘A shilling.’

‘Nah, it’s not werf it.’ He sniffed and wiped his sleeve across his nose. ‘I dunno, though. Maybe it is. It’d buy a packet of fags.’

‘Go on, then.’ The girl’s eyes blazed with the intensity of her bet. ‘There’s a drainpipe next to the window.’

The youth nodded and shinned up it without making a sound. He stuck his hand in the gap and pushed the sash up to make enough space to crawl through.

‘You coming?’ His harsh voice reverberated around the walls of the building.

‘Shhhhhh!’ The girl put a finger to her lips. ‘Go in and unbolt the kitchen door near where I’m standing.’

The youth raised his thumb and disappeared through the opening. Two minutes later he had the door open and the girl slipped through like a shadow.

They were in.

‘Look at the size of this kitchen.’

‘That’s nothing,’ the girl said, taking his arm and leading him along a short corridor into the Great Hall.

‘Cor, this is something.’

The youth’s eyes almost swivelled in their sockets as he took in the vaulted ceiling, the massive stone fireplace, and the chandeliers and sconces, unlit now because of the blackout as well as the late hour. His eyes roamed the walls of oil paintings, mostly portraits, and what looked like hundreds of coats of arms, and the solid oak furniture. He turned to her and gave a low whistle.

‘The nobs know how to live, don’t they?’

The girl pulled a face. ‘They might’ve been nobs in them days but Lord Bingham and his family did a runner when the war started.’

‘Who told you that?’ The youth narrowed his eyes at her.

‘I used to work here, didn’t I?’ the girl said. ‘I got ears. You hear things when you work here.’

He threw a look of disbelief that she could have landed such a job.

‘Wot did you do?’

‘I looked after the special children,’ the girl said proudly as she led him along the corridor to the magnificent library. ‘Well, I did until that bitch nurse reported me.’

‘You weren’t crafty enough. You shouldda hung on to yer job.’ He stared at her. ‘Chance to pinch all kinds of stuff and they’d never notice.’ He stared at her. ‘What she report you about, anyways?’

‘I told them we got a Nazi kid amongst us and we should get rid of him.’

‘How d’ya know that?’

‘I saw a photo of his German pa in his uniform, didn’t I?’ A satisfied smirk curled her lips. ‘I might not be a clever clogs but I know a swastika when I see one. His jacket was full of ’em. I was the only one who dared speak out and got the sack for me trouble.’

‘Phew!’ The youth blew his cheeks out. ‘You never know what goes on in these places, do you?’

The pair padded up the main staircase in their rubber-soled shoes.