Полная версия

Dealing with the Yugoslav Past

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

1 INTRODUCTION

2.1 Definitions

2.2 Epistemological and methodological assumptions

2.2.1 Theory

3 METHODOLOGY AND RESEARCH DESIGN

3.1 Discourse analysis

3.2 Visual analysis

3.3 Museum space as an object of analysis

3.3.1 Introduction

3.3.2 From “curiosity” to “national project”

3.3.3 Museums as spaces of collective memory mediation

3.3.4 Museum as metaphor: Purposes and mechanism

3.3.5 Visitors

3.3.6 Historical museums and world war memorials

3.3.7 The problem of the representation of human remains in a memorial museum

3.3.8 Conclusions to the chapter

3.4 BRIEF HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF YUGOSLAV HISTORY

1945–1950s

1960s

1970s

1980s

4 EMPIRICAL PART

4.1 Macedonia

4.2 Kosovo

4.3 Montenegro

4.4 Bosnia and Herzegovina

4.5 Croatia

5 GENERAL CONCLUSIONS

6 DISCUSSIONS

7 LIST OF REFERENCES

1 INTRODUCTION

In 2009, Tim Judah introduced the descriptive term “Yugosphere,” as a result of his observations of the reemergence of economic, cultural, and political ties of ex-Yugoslav countries. The economic links, which were broken in the 1990s, are being restored, and the neighboring countries collaborate as satisfactory export and import partners with each of the former Yugoslav countries. Bosnia exports to Croatia (17.2 percent) and to Serbia (14 percent); the import from these two countries to Bosnia is mostly on the same level. Macedonia largely exports to Montenegro (28.3 percent) and to Serbia (23.5 percent); 30 percent of Montenegrin products go to Macedonia. More than 11 percent of Kosovo’s trade is either with Serbia or Macedonia or comes through them. Slovenia is not excluded from this list and plays the role of an important investor in the Balkan region; for instance, it was the sixth largest investor in Serbia in the 2000–7 period. Similarly, in Kosovo, Telekom Slovenia is the largest cable TV network operator in the country (Judah 2009, 4). Supermarket chains from Croatia, Serbia, and Slovenia (Konzum, Delta, and Mercator, respectively) are opening outlets across the region; tourism promotions are inviting Serbs to spend their time in Croatia; former Yugoslav brands, such as Croatian Kras and Vegeta, the Slovene Alpsko and Gorenje, Montenegrin wines, and Macedonian fruits and vegetables have returned throughout the region (Judah 2009, 5).

Culturally, Judah notes, these countries are also connected through the local TV channels that are broadcast in the region, as well as pop music, music festivals, or common websites for downloading books, such as Knizevnost.org. Furthermore, cultural patterns are similar. Thus, “anyone on Facebook with friends in the region can see people from one end of the Yugosphere to the other selling or looking for tickets for big bands playing anywhere from Ljubljana to Skopje” (Judah 2009, 9). Therefore, the given term is oriented toward the present to encompass the economic, political, and cultural connections that have appeared since the dissolution of the Yugoslav federation and can be described as “the social networks based on past and present connections of the Yugoslav and post-Yugoslav space” (Bieber 2014, 5).

Continuing Judah’s observation, we may mention the similar intentions with which the given countries are represented toward the integration into the European Union (EU) space, if already not a part of it. Thus, Slovenia has been part of the EU since 2004, Croatia entered the EU in 2014, Serbia and Montenegro are candidate countries, Bosnia and Macedonia are cooperating within the frameworks of EU projects, and Kosovo is fully involved in the EU functioning by being patronized by international institutions.

Consequently, being connected economically and culturally, having common political strategies for entering the EU, can it be presumed that the ex-Yugoslav countries would have produced the similar national memory politics toward the pre-conflict period, that is, socialist Yugoslavia?

The assumption about the harmonized interpretation of the common recent past becomes more debatable if we take into account the ethnic conflicts that still arise. Thus, in September and October 2014 alone, different protests took place throughout the region. For instance, Montenegrin Serbs demanded an end to discrimination and “to protect the Serbian language and the Cyrillic alphabet”[1] in Montenegro; Belgrade both held the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) pride event in September[2] and invited Vladimir Putin as the most prominent guest for the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Belgrade during World War II.[3] The celebrations took place for the first time since 1985 and were moved four days in advance so that the Russian president could be present at the event.

In the same year, the Yugoslavia War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague took place. In fact, there has been insufficient evidence to convict Radovan Karadzic of the Srebrenica genocide.[4] Taking such a broad collection of facts into account, may we predict seeing differently constructed national narratives rather than harmonized interpretations? If so, how will the past be interpreted today in the successor states?

In my research, I would like to compare the representation of the Yugoslav period as it has been constructed by national historical museums of the former Yugoslav countries. I would examine history museums, which are located in the capital cities. Additionally, museums or exhibitions that are specializing in the researched period, located in the same cities, would be also taken into consideration. The selection criteria could be presented through three main categories of institutions, which we may choose for our research: history museum, museums of Yugoslav history, and temporary exhibitions dedicated to Yugoslav history. The third category, describing expositions either grounded on a private initiative or made in nonhistorical museums, may be added if its topic specifically deals with the representations of Yugoslavia. I use the capital’s history museums in order to establish representativeness and to be able to compare all materials under the same conditions. Such sampling criteria enable perceiving the general trends in the construction of the national or official interpretations. However, it has to be mentioned that by focusing on a single type of institutions, we reduce possible multilayered narratives, presented in other cities, and in other types of public cultural spaces. This might be the case for Bosnia and Herzegovina or Kosovo, where several ethno-narratives are competing with each other on the same state level. Visits to Banja Luka, Mitrovica, or Vojvodina might have enriched the knowledge of the competing historical narratives; however, such research requires another design and sampling criteria. Therefore, we reduce our analysis to proposed sampling criteria and study only the main national museums.

My decision to use museums as the main object of analysis is grounded in an understanding of the given institution as a deeply political one, which functions not only for displaying the material and preserving items chosen as heritage objects but also function as the space that helps different groups to use it in their interests and to compete with others. Therefore, the museum is understood by me as a place of the concurrences of the power and meanings; the place where the material talks not only about the history but also about the actors involved in creating meanings.

When I started my research, I determined the complex constructions of the recent past at the museums. The Yugoslav period was sometimes obscured in the museums but turned out to be alive at the pub right around the corner near the museum in one place, while being a “hot topic” in another museum. Sometimes, the museum was becoming a core place for demonstrations of public discontent and, through the activity of protesters, it was becoming clear that society is still actively discussing or labeling the given period in contrasting ways.

The events dedicated to topics somehow related to the issue of Yugoslavia were being and continued to be actualized through the museum space. If there was an opening of an exhibition dedicated to the political prisoners, it escalated the political activism and confrontation of different civil divisions that have a dichotomous vision of the recent socialist past. Such a case took place in Belgrade during the opening of the exposition in the History Museum in April 2014.[5]

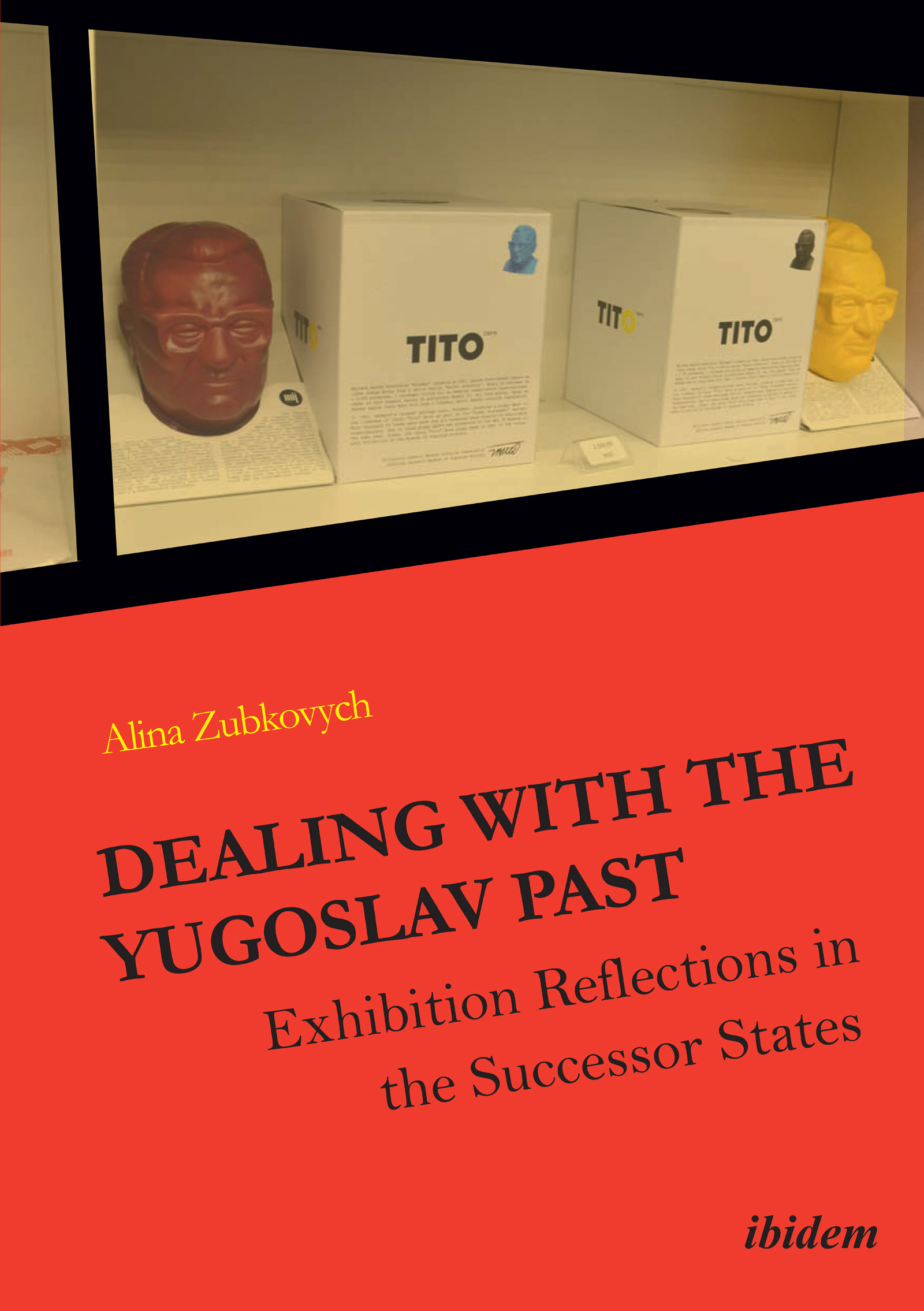

Three months earlier in Belgrade, there was a massively promoted exhibition called “Good Life in Yugoslavia,” which was inviting visitors to immerse themselves into the world of “unity and brotherhood.” There, visitors were able to taste and even to smell Yugoslavia. A similar exhibition, but with the accent on the sacral role and personality of Josip Broz Tito, was gaining momentum in Ljubljana.

The characteristic of all of the aforementioned events was the unfailing popularity of pro- or contra-Yugoslav exhibitions. The aforementioned examples were merely the case of perceptional plurality and polydiscursivity for the broader spectrum of relations toward the past.

I must specify that “Yugoslavia” can have different meanings. Thus, the period of the so-called first Yugoslavia, that is, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which was changed to the “Kingdom of Yugoslavia” in 1929, and existed from 1918 to 1944, may be included on the list. Nevertheless, the word “Yugoslavia” is usually used in both every day and academic language to refer to the so-called second Yugoslavia, that is, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, SFR Yugoslavia, or simply SFRY. The frames of its existence are usually defined as the period from after 1945 until the wars in the former republics of 1992. The third Yugoslavia may also be found in different types of literature; it is used for the identification of the political union of Serbia and Montenegro or the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro, which existed from 1992 to 2006.

The period that was chosen for my research includes the socialist period, thus, the second Yugoslavia, or we may call it the period between two waves of wars: from the end of World War II until the Balkan wars of the 1990s.

The main goal of our research is to discern the key narratives implemented by museums to display the history of the country of the socialist Yugoslav period. The ways and styles of the narration were analyzed with the visual analysis method. Visual analysis was conducted during November 2013 and enriched in the following year.

As for the countries, we have selected the following capital cities for the visit:

· Zagreb, Croatia

· Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

· Skopje, Macedonia

· Pristina, Kosovo

· Podgorica and Cetinje, Montenegro

The list of museums that we have observed consists of the following units:

Macedonia

· Museum of the Macedonian Struggle

· Museum of Macedonia

Kosovo

· Kosovo Museum

· Independence Museum [Kosovo Independence House “Dr. Ibrahim Rugova”]

· Ethnographic Museum [Muzeu Etnologjik Emin Gjiku]

Montenegro

· Podgorica City Museum

· Historical Museum, Cetinje

Bosnia and Herzegovina

· Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Croatia

· Croatian History Museum

· Zagreb City Museum

These museums were chosen because they were the central history museums in the capital cities. Wherever there were museum departments of contemporary or recent history, they were observed as the primary spaces for the analysis. In other cases, when such division was not available, I visited museums that accumulated the “whole” history of the country.

I have chosen the visual analysis method as being the most applicable for the purposes of my research. The essence of this method is closely related to the logic of the selected theory: understanding the context and not taking fragmentary objects for analysis. While each museum will present its national or other specific views of the researched event, discerning the same elements (statements, adjectives by which the viewpoint is formulated) and having the ability to compare them is the basis of the research. The elements of observation as the background of visual analysis aided in making a description of the visual components of the museum.

The political content of the visual data is viewed by me as a precondition for creating the national, transnational, or local identities. Therefore, it is necessary to briefly present several definitions dedicated to an understanding of the given issue.

I have described how I’m going to do my research, mentioning the methods as well as the reasons for choosing museums as the space for research. I have described several important definitions that would be useful for understanding the material presented in other chapters. I have yet to describe what we expect to determine at the museums. For this purpose, I have prepared a list of main questions important for our research.

The main research questions are the following:

The central question: How is the socialist Yugoslav period represented in the historical museums?

The additional sub-questions are proposed next:

Which personalities, events, and periods are chosen to represent the socialist period?

What are the general tendencies of museum politics in relation to the construction of national narratives in the contemporary ex-Yugoslav countries?

What is the dominant narrative of representation of the Yugoslav period in the analyzed countries?

Hypotheses

In my research, we intend to answer the given questions; for better understanding of the national museum politics, I have created hypotheses individually for each country by taking into consideration the differences that each of them had during both the Yugoslav period and the period of dissolution. The brief explanation of the reasons why I think such hypotheses could be seen in the researched countries is also provided.

1. Croatia: The Yugoslav period will be represented through the concept of national repression; Croats will be represented as the nation that suffered the most (the victimization discourse would be predominant); the Goli Otok (Naked Island) will be used as the quintessential symbol of the period.

Explanation: Taking into consideration the national movements that were systematically repressed, Croatian national history will be based on the actualizing of a mournful narrative. The Croatian Spring of 1971–72, the oppressions of Croatian intelligentsia and students that followed, the Serbian and Montenegrin aggression of the 1990s toward territories in Croatia and the Croatian minority in Bosnia and Herzegovina: the whole historical period of Yugoslavia will be presented as a repressive project. Goli Otok will be used, primarily because it is located in Croatia and, secondly, because it fits the narrative of suffering.

2. Bosnia and Herzegovina: When I visited museums located in Sarajevo, I expected to see a unified view; however, we were entirely aware that alternative interpretations would be visible in museums of other cities (e.g., Banja Luka or Brcko, or Mostar). (1) Yugoslavia will be divided into two periods that will be set in opposition to each other: before Tito’s death and after. (2) Yugoslavia before the 1980s will be represented through the discourse of multiculturalism. The Bosniak identity will be given as an example of successful integration of different nations inside the federation. (3) The last decade of its existence will be represented through growing Serbian nationalism and economic instability, which will be the main factors of the explanations for the further Siege of Sarajevo and the conflicts of the 1990s.

3. Montenegro: representation of the “brotherhood and unity” narrative; the period of the 1980s with its growing nationalism will be avoided and not represented at all.

Explanation: Montenegro became an independent country only in 2006 when its union with Serbia collapsed. Consequently, with a pseudo-defensive rhetoric, it has to reorient its political ideology and create a new understanding of the previous two decades as part of an aggressive force. The recent past is still the matter of discussions and a harmonized national interpretation of this period has not yet been produced.

4. Kosovo: The representation will emphasize the elements of Yugoslav authoritarianism. The suppressed Albanian student protests in 1961, as well as the weak economic situation and growing Serbian nationalism of the 1980s would be used as key topics.

Explanation: Kosovo has been actively involved in the nation-building process since its recognition as an independent country. Being the former Yugoslav republic with an Albanian majority, it takes Albanian history as its starting point. The area that has dramatically suffered from being part of Yugoslavia will confront the entire Yugoslav discourse.

5. Macedonia: The exhibition has to balance between glorifying the Yugoslav period associated with a stable economy and relative security, while finding the arguments why Macedonia preferred to become independent in such a situation. The period after World War II will be used to show the reconstruction of the country and the spirit of the collective ideology.

Explanation: Yugoslavia played a sufficient role in creating and fixing the Macedonian identity as opposed to Bulgaria and Greece, which were not part of the federation. Since Macedonia did not have a strong, controversial collective memory of World War II like Croatia and Serbia have (no local “Chetniks,” no “Ustasha”), the post–World War II period could be easily used as a non-conflict one and as the period when the country was exposed to economic development and urban reconstruction.

I hope to conduct research that will not only describe the displays but also will help to find the deeper knowledge hidden at the expositions. In the next parts of the study, a brief historical review of Yugoslav history would be presented. For these purposes, the description of the decades is being used. The description begins with the postwar period (1945) and finishes with the last decade of Yugoslav history: the end of the 1980s. The most important sources for the historical part are derived from the works of Ramet (2005, 2006), Malcolm (1996, 1998), Bartlett (2003), Hupchick (2002), and Luthar (2013).

Chapter 2 presents museums as fields of social research. It sheds some light on the definitions and describes briefly the history of the development of the given institution, its purposes and ways of influence on creating cultural inequalities in different societies. This chapter emphasizes the role of museums in the contemporary world and presents the results of empirical research dedicated to the visitors of the museum. The works of the following authors greatly influenced the writing of this chapter: Appadurai and Breckenridge (1991), Bennett (1995), Kavanagh (1996), Crane (2005), Ostow (2008), Ernst (2000), Guha-Thakurta (2004), Crooke (2004), Duncan and Wallah (2004), Wilkening and Chung (2009), Wilson (2001), Williams (2007), and Bleich (2011).

Chapter 3 represents the methodological part of this study. It is followed by the empirical part of the research, where analysis of each museum and each country is being conducted. Afterward, the outcomes from the national perspective are combined together in order to generalize the characteristics that unify the Yugosphere or distinct cases from each other. The visual analysis is accompanied by the photos made in each of the museums and helps to provide clearer visual confirmation of the extracted dominant discourse.

2 THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

In order to begin with the empirical part, it would be beneficial to describe briefly the main terms commonly used in the given research. Among the most important are “collective memory,” “politics of memory,” “museum politics,” and “representation.” It is followed by the basic examination of the phenomenon of nostalgia and Yugo-nostalgia. The section starts with a brief description of the concept of memory and move toward the concepts related to it.

2.1 Definitions

Memory as an interdisciplinary phenomenon integrates highly diverse elements and does not become irrelevant for many decades. The practices of remembering and forgetting, as such, and reflections on its nature, structure, transformation, and diverse applications turn out to be all-encompassing interdisciplinary social phenomena. Memory has become an important topic in politics and public discourse. It is instantly present when we refer to the context of national, local or transnational tradition, myth, and history. Memory also occupies the central sphere of human life. In everyday life, for instance, it happens in the form of the thriving heritage industry. The preoccupation with memory is visible all over the world; the “memory boom” has become the central characteristic or even diagnosis of contemporary societies. Cultural remembering has always existed, but what makes it a new phenomenon is the facts that discourses on memory are increasingly linked across the globe. Memory is related to a list of phenomena that is growing. Therefore, some scholars are focused on such aspects of memory studies as amnesia and social forgetting (see Huyssen 1995), the dynamic of cultural remembrance (see Rigney 2005), and others.

Keeping memories alive is in line with the contra-phenomenon of forgetting. Paradoxically, in the process of experiencing our reality, we, as a rule, forget things more often than keep them alive in our memory. Therefore, the following definition seems to be relevant for the beginning: “Memories are small islands in a sea of forgetting” (Erll 2011, 9). No doubt, such a brief definition does not include important factors of the process of memorizing, its selective nature and specificity relevant for diverse discourses. Nevertheless, it shows the importance of such aspects as amnesia, oblivion, and silence. In application to our study, such elements become extremely important while being the flip side of the narratives that we analyze in the history museums.

The polysemous concept of memory has an important distinction: collective memory, which is part of the puzzle and to some extent less metaphoric and perhaps more precise in definition. I understand collective memory to be a result of reduced, selected, and homogenized understandings of the past constructed in the process of the interaction of the individual and the intermediary institutions. Museums, in this regard, are institutions that visualize the selected form of collective memory as a signifier code and fix it in a cognitive landscape of the visitor with different dynamics of cultural remembrance. The differences in perceptional dynamics mean that the variations in the level of the habitualization of the “messages” that were provided by the narratives were instantly included into the visual representation of the exhibitions. It has to be noted that the collective memory does not have the quality of universal inclusivity and usually is competing with other sets of collective remembering. For instance, the narrative presented in the national historical museum may be totally different to the ways of interpretation of the same historical period in the parallel institutional structures in other countries, cities, or the same city. The system of relations for the past being produced through the two-sided process of the construction of common knowledge, in which the individual and the intermediary institutions are making this social reality together, form the sets of collective memory that then have a chance to be visualized through the museum spaces. Therefore, the narrative provided by the museum must not only exist but also have some visible representation in the form of artefacts and supporting description. Our goal is to find such elements that form the narrative and to perceive the collective memory narrative to which it is referred.