Полная версия

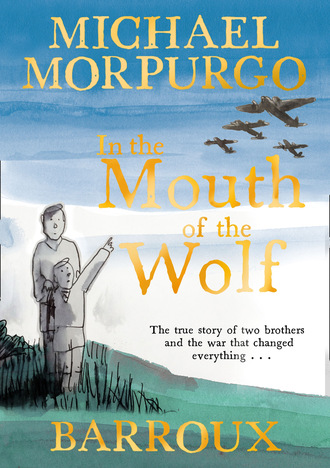

In the Mouth of the Wolf

First published in Great Britain 2018

by Egmont UK Limited

The Yellow Building, 1 Nicholas Road, London W11 4AN

Text copyright © 2018 Michael Morpurgo

Illustrations copyright © 2018 Barroux

The moral rights of the author and illustrators have been asserted.

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material

reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will

be pleased to make restitution at the earliest opportunity.

All images used with thanks.

Two images of Christine Granville here © The Estate of William Stanley Moss

ISBN 978 1 4052 8526 1

eISBN 978 1 4052 9274 0

65511/1

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Printed and bound in Great Britain by the CPI Group

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the

publisher and the copyright owner.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at

the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content

hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and

websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are

supervised when using the internet.

Egmont takes its responsibility to the planet and its inhabitants very seriously.

All the papers we use are from well-managed forests run by responsible suppliers.

For Nan and Francis,

Niki, Jay, Christine and Paul.

And Kia.

In memory of Yves Barroux.

For Marie-Thérèse and Sophie-Laure.

T

hey gave me such a jolly party today. Everyone

from the village came.

Ninety years old, I am. I’m walking a bit stooped

these days, and my knees and hips are more rickety than they should be, but I can walk up into the village, and I still like a good meal, and a glass of good red wine –

I had plenty of that this

evening. Sleep does not

come so easily as it did,

but I mustn’t grumble. I

have my memories, and

friends all around me,

and family too, those who

are still alive. What more

could an old man want?

1

A better memory would be good. I’m fine with faces and places. It’s the years that get muddled, jumbled up. I spend my time trying to unjumble them.

The village mayor made a generous speech, and said how honoured they were to have Monsieur le Colonel Francis Cammaerts – such a great man, and such a great friend to the people of Le Pouget,

and of France – living here in their little French village, and his family too. The school children stood in the courtyard, with their Union Jack and Tricolour flags, and sang ‘Sur le Pont d’Avignon’ and ‘London Bridge is Falling Down’ as well, and everyone clapped and sang ‘Happy Birthday to You’, in English and in French.

3

A little girl stepped forward to present me with some flowers. Red, white and almost-blue irises. Lovely. The mayor said she was the newest girl in the school, that she had recently come from Punjab to live in the village. She spoke with quiet dignity, and in good French. ‘I am Jupjaapun Kaur. From all the children in Le Pouget I wish you a most happy birthday.’ I repeated her name again and again to be sure I was pronouncing it right.

She smiled at me, and told me that Kaur means princess. The flowers, she said, came from her garden.

I was so glad at that moment that we’d come back to live in France, but sad that not all of us were here, that Nan and our Christine were not with us. Several others too. I miss them more today than ever. But I have Paul, and I have Niki. And Jay.

A wonderful son and two dear daughters, and little Kia, who is no longer little at all – grandchildren grow up even faster than your own children. I should be thankful.

4

And I am, I am. But I am in the dusk of my life, a dusk that is streaked with joys, and sadnesses.

I was suddenly tired and longing for the solitude and quiet of my little room, and bed. I waved them all goodbye. Jay helped me into the house, and into bed, hugged me and left. What children I have, what friends they are to me!

So here I am now, in my bed. Night has fallen. The bright moon shining in through the window, and the church bell striking midnight. My scops owl hoots his birthday greeting to me. I smile in the moonlight and settle back on my pillows. I know I won’t sleep.

This is a night for remembering. I want to remember everyone who wasn’t here at my party, all my good companions in life who held my hand, stroked my brow, helped me through. I want to see them again, be with them again, live all my life with them again, from my sandpit days to now. Ninety years.

P

apa, are you there, Papa? You missed a good party. I think of you, and you are sitting there in your

tweed suit, with your bird’s nest of a beard, wreathed in pipe smoke. I always wanted to be like you, Papa, smoke a pipe, write fine poetry, stories and plays, be wise. You were so wise about most things – but not

everything. For a start, you had far

too many children. Four

daughters, all of them

loud with laughter

and full of opinions

– Marie, Elizabeth,

Catherine, Jeanne

– and then there

was Pieter and me;

9

‘the boys’, you called us. There were children tumbling

everywhere, crowding me out of the sandpit, and forever

making plays where I always had to be a tree, because I

was tall.

The sisters chose the plays, took the main parts too.

Pieter was the best actor, but they made him play the

log that Bottom sat on in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

10

Do you remember that, Papa? And I was a tree again of

course. You said Pieter made a very fine log, but you said nothing about me being a very fine tree.

I always liked to have you

to myself, but hardly ever

could. You never read the poems and

stories just to me, always to all of us. I loved the stories,

loved the poems, but I loved you more.

You remember those summer holidays in Belgium, Papa, the country walks in the Ardennes forest where you had grown up as a child? Those were the best times, Papa, just you and me, and Pieter trailing along behind, waving a stick. He always had a stick. I asked him once why he was fencing with it, and he said he was fighting off the wolves. And I said there was no need to fight them, that he could turn and face them, and clap his

11

hands and look brave. And Pieter said no, that if they came close and bared their teeth, if they wanted to eat him up, if they wanted to tear our family to pieces, he had to fight them.

You said, Papa, in your wisdom, in your desire always to be fair, that we were both right. But you had told me all my life that it was ignorance and ancient hatreds and power politics that had dragged Europe into the horrors of the Great War, and that in that war, as in all wars, there were never winners, only sufferers. You set me on my pacifist course early, Papa. It is a philosophy that has guided me and troubled me all my life.

Who knows why you sent me off to that boarding school, banishing me from the family home, from all that was familiar – from you? I was never so miserable, before or since. I lay in my bed each night and raged against you and Mama. I grew away from you, from home and family, more and more each night. In time, Pieter came to join me, and we should have been allies then. But I

14

was older, taller, domineering, and I am ashamed to say, Papa, that I neglected him dreadfully. Worse, I turned my back on him as a brother. He was a new boy, a squirt. I treated him with disdain, disowned him sometimes. I have never forgiven myself.

If I am honest, I think there was jealousy there. I might have been a big cheese, was taller than any other boy in the school, a giant on the rugby field, always surrounded by friends, but Pieter was beautiful, with

15

the face of a young god, kind-hearted always, Mama’s favourite, and at home so full of fun and laughter. But not at school. This was not a place for sensitive souls. He hated it as much as I did.

You didn’t know any of this, did you, Papa? We kept our school life separate, Pieter and I. At home I could be more like a proper brother to him again. Free from the tyranny of that school, we could be ourselves, be brothers, be the best of friends. But, away from you, Papa, I stopped

knowing you. I stopped knowing you, even stopped

loving you for a while. Home was a foreign land to me.

You were busy becoming Emile Cammaerts, travelling up

to London every day, the great professor and poet.

There were no more family holidays in the Ardennes,

no more walks and talks in the forest, just you and me.

There was civil war raging in Spain, Hitler’s bombs

were falling on Guernica, on families, on old and young

alike. And in Germany and in Italy, fascists were on

the move. The world was resounding to the march of

jackboots, the drums of war were beating.

I did my university degree in Cambridge, living the last of the good life, turning a blind eye, hoping for the best, but fearful already that the Great War into which I had been born was not going to be the war to end all wars. I turned to teaching, not out of conviction, not yet, but for lack of anything else to do. You approved, and told me I would make a great teacher. I wanted so much to believe that.

I hardly saw Pieter those days. He was going his own way, as a proper actor – not just a log any more – travelling

the country. If I ever came home, you would show me his reviews proudly. You forgave me for drifting away, let me become whoever I was going to become. You trusted me, and that takes love, I know that now. You made me who I am, Papa. And Pieter? Well, Pieter changed the whole course of my life.

T

he scops owl is still hooting to the world, to me,

wishing me a happy birthday. But the church bell

has chimed one o’clock. So my birthday is well and truly over. A cloud is passing over the moon, darkening my room. I don’t like the dark, never have. Nor did Pieter. He hated to be alone at night. When he was little he often used to come into my room and crawl into my bed.

I never told Pieter I was frightened of

the dark too. We used to count the

stars we could see to take our

minds off the dark, and I would

teach him the names of all the

stars I knew. He told me once

how much he longed to go there,

to the stars.

You there, Pieter? You up there in the stars? Missed

you at the party. Or were you there maybe? Been a long time, little brother. What is it, nearly seventy years since I watched you get on that chuffa-chuffa train, as you used to call them, at Radlett Station? I knew then, as the train pulled out and you were waving at me out of the window, that I wouldn’t see you again. As you disappeared

into the smoke, I wanted to shout after you to come back. I glimpsed it in your face, that you knew what I feared, that you didn’t need me to warn you. You were doing what you believed was right. You didn’t need me at all, not any more. What you didn’t know, because I never told you, was how much I needed you then and have needed you since, every day, all my life.

22

We did everything together, didn’t we, Pieter? With Papa away at work up in London even during the school holidays, you were the only one at home I could really talk to. We swam, we cycled, we climbed trees, we learnt to drive together, learnt about girls together too. Learning to drive was a whole lot easier.

There came a day when we had both grown away from home, and were not big brother and little brother any more. I had left university and you were at drama college and were acting at Stratford-upon-Avon – Julius Caesar, it

was, and you were the best actor in the play, no question. I was so proud of you in your toga, so envious of your great gift. How could that little boy who had trailed behind me in the forest, fencing off the wolves with his stick, longing to go to the stars, have become such a great actor?

We took a rowing boat out for a picnic on the river, tied up under a willow tree, and we talked properly, maybe for the first time. We argued, not angrily but passionately, about Hitler and Mussolini, about the war

24

we knew was coming. I spoke of the futility and waste of war, of the barbarity and horror of the Great War, of how we must not descend to the level of the fascists and join in another conflict that would only serve to kill more millions. I insisted that pacifism was the only way forward for humanity.

And you surprised me with the force of your argument. You said that you had always respected my views, but that I was wrong, that pacifism would not stop Hitler, that the cruelty of fascism had to be confronted. Hitler had marched into Austria, and into Czechoslovakia and Poland, and everyone knew his tanks would soon be rolling into Alsace-Lorraine, you said. The freedom of Europe, of the whole world, was threatened. If it came

to war, you would join up and fight. You said you loved acting, but you couldn’t go on making make-believe on the stage when the survival of everyone and everything you held dear was at stake. And I told you – and how well I remember saying it – that killing another human being,

25

no matter how worthy the cause, was wrong, was as wicked as any evil, as any tyrant you might be fighting. Wars solve nothing. I was adamant.

You simply smiled at me as you were rowing, and said, ‘We must each do what we must do, Francis.’ Then you looked down at my bare feet in the bottom of the boat, and laughed. ‘Strewth, I had forgotten what big feet you have! That’s what they called you at school, you know, when you weren’t listening. “Big Feet”.’ You wriggled your own feet then, and said, ‘See those? Small feet, Francis. I always wanted them to be bigger, like yours. I think maybe we all have to get used to our own feet.’ This was my new brother, no longer little, a brother with a mind of his own, a wonderful man.

So you went your way, and I went mine. Neither you nor I wrote letters if we could help it. We met occasionally, awkwardly, at family gatherings which I never enjoyed. The family gloried in your success and would send me reviews from time to time. ‘Pieter Cammaerts is

27

remarkable, a tour de force.’ ‘Pieter Cammaerts, a star in the making.’

And whilst you were gathering these accolades during that last spring and summer of peace, I was still trying to discover where my big feet might take me. You had always been so sure of yourself. You set out to be a great actor and that’s what you became. As for me, I found myself one day standing there in front of a class of forty children, trying to be a teacher. Teach and teach well, I thought, give the children the opportunities they deserve. That was the only way to make the world a better, more peaceful place.

You know me, Pieter, ever full of high-minded notions and pontifications. But these notions weren’t of much use to me in front of all those children, most of whom were not at all keen to learn. Being big and tall helped, I found. I frightened them at first. ‘Mr Giant’ they called me. ‘Big Feet’ too. I would sometimes hear a whispered chorus of ‘Fee fi fo fum’, when they saw me coming.

I learnt plenty from one or two other teachers at the

28

school, Harry in particular. He taught me that you had

to be on their side, and they had to know it, that mutual respect and affection was the key. I was discovering for myself that I had in the class forty expectant faces gazing up at me, forty intellects waiting to be stimulated, forty hearts waiting to be moved to laughter or tears, through stories and poems and plays. I had to get to know what made each of them tick, and to do that I had to learn to listen to them, and understand them. They had to know they had a friend in me as well as a teacher.

I tried to pass on to them all the things I had loved as a child, all I had done with you and Papa in the Ardennes. I walked the river banks with them, looking for otters and herons and kingfishers, walked the wild woods when the bluebells were out, discovered foxholes with them, watched larks rising over the fields. It was quite unexpected, but I fell in love with teaching, and knew quickly I would make it my life.

29

But much like you with your acting, Pieter, Adolf Hitler changed all that. He marched his armies into Poland, as you had said he would, bombed Warsaw. Still I hoped and believed there could be peace. Can you imagine? I saw what was happening, we all did. His tanks roared into Holland, through the Ardennes, through Papa’s forest, our forest, into our beloved Belgium.

You did what you said you would, left your toga behind in the theatre, and put on your blue RAF uniform instead. And you looked perfect in that part too. You were training for months somewhere up in Scotland, but you didn’t want to talk about it. All you said was that now you were a Sergeant Navigator you probably knew the stars better than I did.

We had a last Sunday lunch back at home with the family, you in your uniform. Then I walked you to the station and we waited for your train over a cup of tea. There was a silence between us, not because we were strangers – it was more a silence of foreboding. It was

32

raining when the train came in. We held on to one another, neither of us wanting to let go. You went on waving from the train window for as long as you could see me. And that was that.

You went off west to join your bomber squadron in Cornwall, and I went off north to Lincolnshire, to work on a family farm. I had had to go before a tribunal to explain why I felt I would not and should not put on a uniform and fight in this war, or any war. They had listened grim-faced, told me I was wrong, but accepted my sincerity. I had to contribute to the war effort in other ways, they said. I would have to go to work on a farm. The nation needed food.

So I found myself milking cows, mucking them out, feeding pigs, mucking them out, feeding hens, mucking them out. Lots of mucking out. I loved the sheep best, especially lambing time. I drove the tractor, helped with the hay and straw harvest, dug up turnips and potatoes. I learnt more in a few months, Pieter, than I had in all my time in university. I grew fit and strong too, and that was to be important.

In the farmhouse I lived amongst fellow pacifists, all of us wanting to forget the war, but never being able to.

35

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.