Полная версия

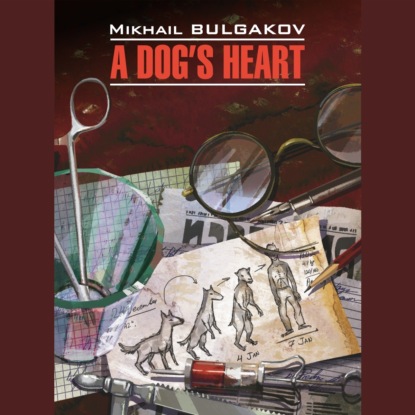

A dog's heart (A Monstrous Story) / Собачье сердце (Чудовищная история). Книга для чтения на английском языке

Broken glass tinkled as it was swept up, and a woman’s voice noted flirtatiously: “Cracow sausage! God, you should have gotten him two copecks’ worth of scraps at the butcher! I’ll eat the Cracow sausage myself.”

“Just try! I’ll eat you! It’s poison for the human stomach. A grown young woman and you’re like a baby sticking all kinds of nasty things in your mouth. Don’t you dare! I’m warning you, neither Doctor Bormental nor I will bother with you when you get the runs[22]. ‘Everyone who says that another is your match…’”

Soft staccato bells jingled throughout the apartment, and in the distance voices sounded frequently in the entrance. The telephone rang. Zina vanished.

Filipp Filippovich tossed his cigarette butt in the bucket, buttoned his coat, smoothed his luxurious moustache in the mirror on the wall and called the dog.

“Phweet, phweet… come on, come on, it’s fine! Let’s go receive.”

The dog got up on unsteady legs, swayed and trembled, but quickly got his bearings[23] and followed the fluttering coat-tails of Filipp Filippovich. Once again the dog crossed the narrow corridor, but now he saw that it was brightly lit from above. When the lacquered door opened, he followed Filipp Filippovich into the office, which blinded the dog with its interior. First of all, it was blazing with light: it burned on the plaster ornamented ceiling, it burned on the desk, it burned on the wall and in the cupboard glass. Light poured over a myriad of objects, of which the most amusing was an enormous owl, sitting on a branch on the wall.

“Stay,” ordered Filipp Filippovich.

The carved door opposite opened and the bitten man came in, and now in the bright light revealed as a very handsome young fellow with a pointy beard, and handed over a piece of paper, muttering, “The previous.”

He vanished silently, while Filipp Filippovich smoothed the tails of his lab coat and sat behind the huge desk, thereby becoming incredibly important and imposing.

“No, this isn’t a hospital, I’ve landed in some other place,” the dog thought in confusion and flopped on the carpet by the heavy leather sofa, “and we’ll figure out that owl too.”

The door opened softly and someone came in, astonishing the dog enough to make him yap, but very diffidently.

“Quiet! Well, well, well! You’re unrecognizable, dear fellow.”

The newcomer bowed very respectfully and awkwardly to Filipp Filippovich.

“Hee-hee! You are a magician and sorcerer, professor,” he muttered in embarrassment.

“Take off your pants, dear fellow,” Filipp Filippovich commanded and stood up.

“Jesus!” thought the dog. “What a fruitcake!”

The fruitcake’s head was covered with completely green hair, and at the back it had a rusty tobacco shimmer. Wrinkles spread out on the fruitcake’s face, but his complexion was as pink as a baby’s. His left leg couldn’t bend and he had to drag it along the carpet, but the right one jerked like a toy nutcracker. On the lapel of his magnificent jacket, a precious stone protruded like an eye.

The dog was so interested that his nausea passed.

“Yip, yip,” he barked softly.

“Quiet! How are you sleeping, dear fellow?”

“Hee-hee… Are we alone, professor? It’s indescribable,” the visitor said in embarrassment. “Parole d'honneur[24], I’ve seen nothing like it for twenty-five years!” The subject touched the button of his trousers. “Can you believe it, Professor? Every night there are herds of naked girls. I am positively delighted. You are a sorcerer!”

“Hmmm,” grunted Filipp Filippovich in concern, peering into his guest’s pupils.

The latter had finally mastered the buttons and removed his striped trousers. Beneath them were unimaginable underpants. They were cream-coloured, with embroidered black silk cats, and they smelt of perfume. The dog couldn’t resist the cats and barked, making the subject jump.

“Ai!”

“I’ll whip you! Don’t be afraid, he doesn’t bite.” “I don’t bite?” the dog was surprised.

A small envelope, with a picture of a beautiful girl with loosened tresses, fell out of the trousers pocket onto the floor. The subject jumped up, bent over, picked it up and blushed a deep red.

“You’d better watch it,” Filipp Filippovich warned grimly, wagging his finger, “Do be careful not to abuse it!”

‘I’m not abu…” the subject muttered in embarrassment, still undressing. “This was just an experiment, dear Professor.”

“Well, and what were the results?” Filipp Filippovich asked sternly.

The subject waved his arm ecstatically.

“In twenty-five years, I swear to God, Professor, there was nothing like it! The last time was in 1899 in Paris on the Rue de la Paix[25].”

“And why have you turned green?”

The visitor’s face darkened.

“That damned Zhirkost![26] You cannot imagine what those useless louts fobbed off on me instead of dye. Just look,” he babbled, his eyes searching for a mirror. “It’s terrible! They should be punched in the face,” he added, growing angrier. “What I am supposed to do now, Professor?” he asked snivelling.

“Hm… Shave it all off.”

“Professor!” the visitor exclaimed piteously, “It will grow back grey again! Besides which, I won’t be able to show my face at work, I’ve been out three days now as it is. The car comes for me and I send it away. Oh, Professor, if you could discover a way of rejuvenating hair as well!”

“Not right away, not right away, dear fellow,” muttered Filipp Filippovich.

Bending over, he examined the patient’s bare belly with glistening eyes. “Well, it’s lovely, everything is perfectly fine… I didn’t expect such a fine result, truth to tell. ‘Lots of blood and lots of songs!’. Get dressed, dear fellow!”

“‘And for the loveliest of all!..’ the patient sang the next line in a voice as resonant as a frying pan and, glowing, started dressing. Having brought himself back to order, hopping and exuding perfume, he counted out a wad of white banknotes for Filipp Filippovich and tenderly pressed both of his hands.

“You need not return for two weeks,” Filipp Filippovich said, “but I do ask that you be careful.”

“Professor!” from beyond the door, in ecstasy, the guest exclaimed. “Do not worry in the least.” He giggled sweetly and vanished.

The tinkling bell flew through the apartment, the lacquered door opened, the bitten one entered, handing Filipp Filippovich a piece of paper and announced: “The dates are incorrectly given. Probably 54–55. Heart tones low.”

He vanished and was replaced by a rustling lady with a hat at a rakish angle and a sparkling necklace on her flabby and wrinkled neck. Terrible black bags sagged beneath her eyes, but her cheeks were a doll’s rouge colour.

She was very agitated.

“Madam! How old are you?” Filipp Filippovich asked very severely.

The lady took flight and even paled beneath the crust of rouge.

“I, Professor… I swear, if you only knew, my drama…”

“How old, Madam?” Filipp Filippovich repeated even more severely.

“Honestly. well, forty-five-”

“Madam!” Filipp Filippovich cried out. “People are waiting! Don’t hold me up, please, you are not the only one!”

The lady’s bosom heaved mightily.

“I’ll tell you alone, as a luminary of science, but I swear, it is so terrible-”

“How old are you?” Filipp Filippovich demanded angrily and squeakily, and his glasses flashed.

“Fifty-one,” the lady replied, cowering in fear.

“Take off your pants, Madame[27],” Filipp Filippovich said in relief and indicated a tall white scaffold in the corner.

“I swear, Professor,” the lady muttered, undoing some snaps on her belt with trembling fingers, “That Moritz… I am confessing to you, hiding nothing…”

“‘From Seville to Granada,’” Filipp Filippovich sang distractedly and stepped on the pedal under the marble sink. Water poured noisily.

“I swear to God!” the lady said, and live spots of colour broke through the artificial ones on her cheeks, “I know that this is my last passion. He’s such a scoundrel! Oh, Professor! He’s a card shark, all of Moscow knows it. He can’t let a single lousy model get by. He’s so devilishly young!” The lady mumbled and pulled out a crumpled lacy clump from beneath her rustling skirts.

The dog was completely confused and everything went belly up in his head.

“The hell with you,” he thought dimly, resting his head on his paws and falling asleep from the shame, “I won’t even try to understand what this is, since I won’t get it anyway.”

He was awaked by a ringing sound and saw that Filipp Filippovich had tossed some glowing tubes into a basin.

The spotted lady, pressing her hands to her breast, gazed hopefully at Filipp Filippovich. He frowned importantly and, sitting at his desk, made a notation.

“Madame, I will transplant ape ovaries in you,” he announced and looked severe.

“Ah, Professor, must it be an ape?”

“Yes,” Filipp Filippovich replied inexorably.

“When will the operation take place?” the lady asked in a weak voice, turning pale.

“‘From Seville to Granada’… hm… Monday. You will check into the clinic in the morning and my assistant will prepare you.”

“Ah, I don’t want to be in the clinic. Can’t you do it here, Professor?”

“You see, I do surgery here only in extreme situations. It will be very expensive, five thousand.”

“I’m willing, Professor!”

The water thundered again, the feathered hat billowed, and then a head as bald as a plate appeared and embraced Filipp Filippovich. The dog dozed, the nausea had passed, and the dog enjoyed the calmed side and warmth, even snored a little and had time for a bit of a pleasant dream: he had torn a whole bunch of feathers from the owl’s tail. Then an agitated voice bleated overhead:

“I am a well-known figure, Professor! What do I do now?”

“Gentlemen!” Filipp Filippovich shouted in outrage. “You can’t behave this way! You have to control yourself! How old is she?”

“Fourteen, Professor… You realize that the publicity will destroy me. I’m supposed to be sent to London on business any day now.”

“I’m not a lawyer, dear fellow. So, wait two years and marry her.”

“I’m married, Professor!”

“Ah, gentlemen, gentlemen!”

Doors opened, faces changed, instruments clattered in the cupboard, and Filipp Filippovich worked without stop.

“A vile apartment,” the dog thought, “but how good it is here! What the hell did he need me for? Is he really going to let me live? What a weirdo! A single wink from him and he’d get such a fine dog it would take your breath away! Maybe I’m handsome too. It’s my good luck! But the owl is garbage. Arrogant.”

The dog woke up at last late in the evening, when the bells stopped and just at the instant when the door let in special visitors. There were four at once. All young people, and all dressed very modestly.

“What do these want?” the dog thought with surprise. Filipp Filippovich greeted them with much greater hostility. He stood at his desk and regarded them like a general looking at the enemy. The nostrils of his aquiline nose flared. The arrivals shuffled their feet on the carpet.

“We are here, Professor,” said the one with a topknot of about a half foot of thick, curly black hair, “on this matter-”

“Gentlemen, you shouldn’t go around without galoshes in this weather,” Filipp Filippovich interrupted edifyingly. “First, you will catch cold, and second, you’ve left tracks on my carpets, and all my carpets are Persian.”

The one with the topknot shut up and all four stared in astonishment at Filipp Filippovich. The silence extended to several seconds and it was broken by Filipp Filippovich’s fingers drumming on the painted wooden plate on his desk.

“First of all, we’re not gentlemen,” said the youngest of the four, who had a peachy look.

“First of all,” interrupting him as well, Filipp Filippovich asked, “are you a man or a woman?”

The four shut up and gaped once again. This time the first one, with the hair, responded. “What difference does it make, Comrade?” he asked haughtily.

“I’m a woman,” admitted the peachy youth in the leather jacket and blushed mightily. After him, one of the other arrivals, a blond man in a tall fur hat, blushed dark red for some reason.

“In that case, you may keep your cap on; but you, gracious sir, I ask to remove your headgear,” Filipp Filippovich said imposingly.

“I’m not your ‘gracious sir’,” the blond youth muttered in embarrassment, removing his hat.

“We have come to you-” the dark-haired one began again.

“First of all, who is this ‘we’?”

“We are the new managing board of our building,” the dark one said with contained fury. “I am Shvonder, she is Vyazemskaya, he is Comrade Pestrukhin, and Sharovkin. And so we-”

“You’re the ones who have been moved into the apartment of Fyodor Pavlovich Sablin?”

“We are,” Shvonder replied.

“God! The Kalabukhov house is doomed!” Filipp Filippovich exclaimed in despair and threw his hands up in the air.

“What are you laughing about, Professor?”

“I’m not laughing! I’m in complete despair!” shouted Filipp Filippovich. “What will happen to the central heating now?”

“You are mocking us, Professor Preobrazhensky!”

“What business brings you here? Make it fast, I’m on my way to dinner.”

“We, the Building Committee,” Shvonder said with hatred, “have come to you after the general meeting of the residents of our building, on the agenda of which was the question of consolidating the apartments.”

“Where was this agenda?” screamed Filipp Filippovich. “Make an effort to express your ideas more clearly.”

“The question of consolidating-”

“Enough! I understand! You know that by the resolution of 12th August of this year my apartment is exempt from all and any consolidation and resettlement?”

“We know,” Shvonder replied, “but the general meeting examined your case and came to the conclusion that in particular and on the whole you occupy an excessive space. Completely excessive. You live alone in seven rooms.”

“I live and work alone in seven rooms,” replied Filipp Filippovich, “and I would like to have an eighth. I need it as a library.”

The foursome froze.

“An eighth! Ho-ho-ho,” said the blond man deprived of his headgear, “that’s really something!”

“It’s indescribable!” explained the youth who turned out to be a girl.

“I have a reception – note that it is also the library – a dining room and my study – that’s three. Examining room, four. Operating room, five. My bedroom makes six, and the maids’ room is seven. Basically, it’s not enough… But that’s not important. My apartment is exempt and that’s the end of the conversation. May I go to dinner?”

“Sorry,” said the fourth, who looked like a sturdy beetle.

“Sorry,” Shvonder interrupted, “it is precisely the dining room and examining room that we came to discuss. The general meeting asks you voluntarily, as part of labour discipline, to give up the dining room. No one has dining rooms in Moscow anymore.”

“Not even Isadora Duncan!”[28] the woman cried out resoundingly.

Something happened to Filipp Filippovich, the consequence of which was a gentle reddening of the face, but he did not utter a sound, waiting for what would come next.

“And the examining room too,” Shvonder continued. “The examining room can easily be combined with the study.”

“Ah-ha,” said Filipp Filippovich in a strange voice. “And where am I supposed to partake of meals?”

“In the bedroom,” all four chorused.

Filipp Filippovich’s crimson colour took on a greyish cast.

“Take food in the bedroom,” he said in a slightly stifled voice, “read in the examining room, dress in the reception room, operate in the maid’s room, and examine people in the dining room? It’s quite possible that Isadora Duncan does just that. Maybe she dines in the study and cuts up rabbits in the bathroom. Perhaps. But I am not Isadora Duncan!” he burst out, and his purple colour turned yellow. “I will eat in the dining room and operate in the operating room! Tell this to the general meeting, and I entreat you humbly to return to your affairs and allow me to take food where all normal people do – that is, in the dining room, and not in the entrance and not in the nursery.”

“Then, Professor, in view of your stubborn resistance,” said agitated Shvonder, “we will file a complaint against you higher up.”

“Aha,” Filipp Filippovich said, “is that so?” His voice took on a suspiciously polite tone. “I’ll ask you to wait a minute.”

“That’s some guy,” thought the dog delightedly. “Just like me. Oh, he’s going to nip them now, oh, he will! I don’t know how yet, but he’ll nip them!.. Hit them! Take that long-legged one right above the boot on his knee tendon. Grrrrr.”

Filipp Filippovich picked up the telephone receiver with a bang and said this into it: “Please. yes. thank you. Vitaly Alexandrovich, please. Professor Preobrazhensky. Vitaly Alexandrovich? Very glad to find you in. Thank you, I’m fine. Vitaly Alexandrovich, your operation is being cancelled. What? No, cancelled completely, just like all the other operations. Here is why: I am stopping work in Moscow and in Russia in general. Four people just came in to see me, one of them is a woman dressed as a man and two are armed with revolvers, and they terrorized me in my apartment with the goal of taking part of it away-”

“Excuse me, Professor,” Shvonder began, his expression changed.

“Sorry. I do not have the opportunity to repeat everything they said, I’m not interested in nonsense. It is enough to say that they proposed I give up my examining room, in other words, making it necessary to operate on you where I have been slaughtering rabbits until now. In such conditions I not only cannot work but I do not have the right to work. Therefore, I am ending my activity, closing up the apartment, and moving to Sochi. I can turn over the keys to Shvonder, let him perform the operations.”

The foursome froze. Snow melted on their boots.

“What else can I do?… I’m very unhappy about it myself. What? Oh, no, Vitaly Alexandrovich! Oh no! I will not continue this way. My patience has run out. This is the second time since August. What? Hm… As you wish. But at least. But only on this condition: from whomever, whenever, whatever, but it must be a paper that will keep Shvonder and everyone else from even approaching the door to my apartment. A final paper. Factual. Real. A seal. So that my name is not even mentioned. Of course. I am dead to them. Yes, yes. Please. Who? Aha. Well, that’s better. Aha. All right. I’ll pass the phone over. Please be so kind,” Filipp Filippovich said in a snake-like voice, “someone wants to speak to you.”

“Excuse me, Professor,” Shvonder said, flaring up and then fading, “you perverted our words.”

“I will ask you not to use such expressions.”

Shvonder distractedly took the receiver and said, “I’m listening. Yes. chairman of the BuildCom. We were acting in accordance with the rules… the professor is in a completely exceptional situation as it is. We know about his work. we were going to leave an entire five rooms. well, all right. if that’s the case. all right…”

Completely red, he hung up and turned.

“He really showed him! What a guy!” the dog thought in delight. “Does he know some special word? You can beat me all you like now, but I’m not ever leaving here!”

Three of them, mouths agape, stared at the humiliated Shvonder.

“This is shameful,” he muttered diffidently.

“If we were to have a discussion now,” the woman began, excited and with flaming cheeks, “I would prove to Vitaly Alexandrovich…”

“Forgive me, you’re not planning to open the discussion this minute, are you?” Filipp Filippovich asked politely.

The woman’s eyes burned.

“I understand your irony, Professor, we will be leaving. Only. As chairman of the cultural section of the building-”

“Chair-wo-man,” Filipp Filippovich corrected.

“I want to ask you,” and here the woman pulled out several bright and snow-sodden magazines from inside her coat, “to buy a few magazines to help the children of France. Half a rouble each.”

“No, I won’t,” Filipp Filippovich replied brusquely, squinting at the magazines.

Total astonishment showed on their faces, and the woman’s complexion took on a cranberry hue.

“Why are you refusing?”

“I don’t want to.”

“Don’t you feel sympathy for the children of France?”

“I do.”

“Do you begrudge the fifty copecks?”

“No.”

“Then why?”

“I don’t want to.”

A silence ensued.

“You know, Professor,” said the girl after a deep sigh, “If you weren’t a European luminary and you weren’t protected in the most outrageous manner (the blond man tugged at the hem of her jacket, but she waved him off) by people whom, I am certain, we will discover, you should be arrested!”

“For what exactly?” Filipp Filippovich asked with curiosity.

“You hate the proletariat!” the woman said hotly.

“Yes, I don’t like the proletariat,” Filipp Filippovich agreed sadly and pressed a button. A bell rang somewhere. The door to the hallway opened.

“Zina,” Filipp Filippovich shouted. “Serve dinner. Do you mind, gentlemen?”

The foursome silently left the study, silently went through the reception, silently through the entrance, and behind them came the sound of the front door shutting heavily and resoundingly.

The dog stood on his hind legs and performed a kind of prayer dance before Filipp Filippovich.

Chapter 3

The dishes, painted with paradisaical flowers and a wide black rim, held thin slices of salmon and marinated eel. On the heavy board was a chunk of sweating cheese, and in a silver bowl, surrounded by snow, was caviar. Among the plates stood several slender shot glasses and three crystal decanters with vodkas of different colours. All these objects resided on a small marble table cosily nestled up against the enormous carved oak sideboard, erupting with bursts of glass and silver light. In the centre of the room stood a table, as heavy as a gravestone, under a white cloth, and on it were two settings, napkins folded into bishops’ mitres and three dark bottles.

Zina brought in a covered silver dish with something grumbling inside. The fragrance coming from the dish made the dog’s mouth fill with watery saliva instantly. “The Gardens of Semiramide!”[29] he thought and started banging his tail like a stick on the parquet floor.

“Bring them here!” Filipp Filippovich commanded with the air of a predator. “Doctor Bormental, I tell you, leave the caviar be! If you would like to take some good advice, have the ordinary Russian vodka, not the English.”

The handsome bitten one (he was no longer wearing the lab coat but was in a decent black suit) shrugged his broad shoulders, chuckled politely, and poured himself the clear vodka.

“The newly blessed?”[30] he enquired.

“Bless you, dear fellow,” the host replied. “It’s spirit alcohol. Darya Petrovna makes excellent vodka herself.”

“You know, Filipp Filippovich, everyone says that it’s quite decent now. Sixty proof[31].”

“But vodka must be eighty proof, not sixty, first of all,” Filipp Filippovich interrupted with a lecture. “And secondly, God only knows what they may have added to it. Can you predict what they could come up with?”

“Anything at all,” the bitten one said confidently.

“I am of the same opinion,” added Filipp Filippovich and tossed the contents of his glass as a single lump into his throat. “Eh… Mmm… Doctor Bormental, I entreat you: take this thing instantly, and if you say it’s not… then I will be your mortal enemy for life. ‘From Seville to Granada…’”

With those words, he hooked something resembling a small dark loaf of bread on his palmate silver fork. The bitten one followed his example. Filipp Filippovich’s eyes glowed.

“Is this bad?” Filipp Filippovich asked, chewing. “Is it? You tell me, esteemed doctor.”

“It’s exquisite,” the bitten one replied sincerely.

“Of course. Please note, Ivan Arnoldovich, that only the remaining landowners not yet slaughtered by the Bolsheviks use cold hors d’oeuvres[32] or soup as zakuski for vodka.[33] Any even slightly self-respecting person operates with hot zakuski. And of the hot zakuski of Moscow, this is number one. They used to be prepared marvellously once upon a time at the Slavyansky Bazaar. Here!”

“You’re giving the dog food from the table,” a woman’s voice sounded, “and then you won’t be able to lure him out of here with a fresh-baked round loaf.”