Полная версия

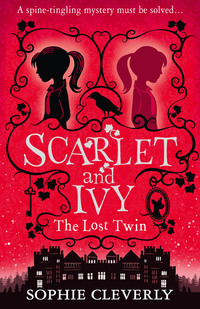

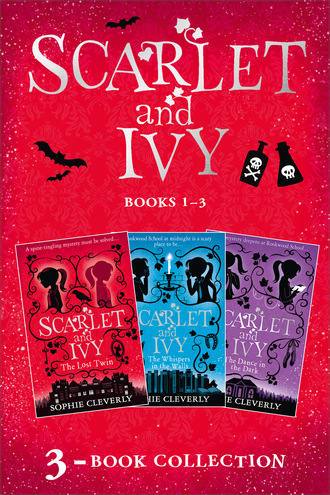

Scarlet and Ivy 3-book Collection Volume 1

Scarlet making a fortress from blankets, protecting her dolls from the Viking Hordes. (That would be me. I wasn’t much of a horde.)

Scarlet leaving trails of painted Easter eggs around our garden, making me find them with clues and riddles. (Our stepbrothers always tried to smash them.)

Scarlet brushing her hair for a hundred strokes before she would let me plait it.

Scarlet hunched over her diary, scribbling away, her tongue poking out of the corner of her mouth.

My sister always wrote in her diary. Every little event had to be pinned to the page. I never saw the point of it then, but she always said that if she didn’t write down everything that happened, it would just disappear forever. There would be no one to remember.

I told her that I would remember, always, but she just laughed and took no notice.

I started picking at the stitching of the seat nervously. There was no way that Scarlet would have been afraid in this situation. She would have taken it in her stride, asked all the questions I wanted answers to. But Ivy Grey never asked questions. Well, not difficult ones anyway. I always just did as I was told.

“Stop that, child,” Miss Fox hissed. “And sit properly!”

I looked up from my lap, but she had already turned away.

Scarlet would have answered back. Scarlet would have drummed her feet on the seats. Scarlet would have ripped out every bit of that stupid stitching.

I did as I was told.

Soon the road widened, and more houses slid into view. I saw a dark-haired man digging his garden, wiping the sweat from his brow with a handkerchief. His beard and strong features reminded me of Father, and I felt a sudden pang of guilt – I hadn’t even spoken to him for months. He was working in London, I supposed. The economy was still reeling from the Crash and it had left him working all the hours he could.

It wasn’t as if I was close to our father. When we were younger, he had been a fiery man, always shouting. But soon after our stepmother came along, he became different. Scarlet was relieved; she was grateful for the peace, didn’t miss the fire. She could never understand why I would prefer the man who shouted at us to the man who spent long hours withdrawn, blank-faced.

With three boys to spoil, our stepmother swiftly decided it was too much for her to keep looking after us as well. That was when she suggested that he ship us off to boarding school.

If only he hadn’t sent us away. If only we’d stayed together.

If only …

The car slid through a pair of enormous gates. Beside them were pillars topped with stone rooks in flight, their wings spread wide and claws grasping at the air.

A long drive snaked its way up to the school, through a cloak of trees and past what looked like a lake shimmering in the distance. We came to a halt and I heard the driver’s feet hit the gravel as he climbed out.

“Watch your step, miss,” he said, pulling open the door.

I smiled up at him as best I could as I clambered out with my bag.

Rookwood School loomed over me, huge and imposing. The bright green trees that lined the drive looked lost in the gloom of the building. The walls were stone – the highest parts blackened by years of chimney smoke. Dark pillars stretched towards the sky in front of me, and crenellations framed the vast slate roof.

It looked like a castle. Or a prison.

It took all my strength not to turn and run back down the length of the drive. Of course, even if I had, I would surely have been caught and punished.

Rooks flew past overhead, their loud caws mixing with the distant shrieks of girls playing hockey.

“Don’t just stand there gaping, girl.” Miss Fox was looking at me like I was an unexpected slug on the sole of her shoe. “Follow me, unless you think you have something better to do.”

“Yes, Miss … no, Miss.”

She turned around, muttering something that I couldn’t hear.

I followed her up the front steps, her sharp shoes clacking and pockets jangling. The front doors were huge, and despite being ancient they swung open without even the smallest creak when she pushed through them. Inside there was a double-height room with a gallery running all the way around. It smelt strongly of floor polish.

In the middle sat an oak desk and a somewhat lost-looking secretary. She was shuffling papers in what I thought was an attempt to look busier than she actually was.

Miss Fox approached the desk and leant on it with both hands.

“Good afternoon, madam,” the secretary said quietly, as Miss Fox’s shadow fell across her.

“Some would say so,” replied Miss Fox, glowering. “I have a child here. Scarlet Grey.” I started to correct her, but she waved an uncaring hand in my face and carried on speaking. “She will begin attending classes tomorrow. Sign her in on the register, please.”

Miss Fox must have been the only person who could pronounce the word ‘please’ like it actually meant ‘RIGHT NOW’.

“D-do you want me to escort her to her room, madam?” asked the secretary.

Miss Fox blinked. “No, I am going to take her to my office to … fill her in. Get her signed up.”

She strode away towards the corridor and I hurried after her. I risked a backward glance at the secretary, who stared at me with wide eyes.

We went past rows of doors, each with a little window revealing the class studying inside. The girls were sat in rows, silent and serious. I was used to a quiet school, but in here there was an air of … wrongness. Like it was too quiet, somehow.

The only sounds were our footsteps and the ever-present jangling from Miss Fox’s pockets. When we reached her office, she pulled out a silver key from one of them and unlocked the door.

The room was dimly lit and smelt of old books. There was a single desk with a couple of high-backed chairs and some tall shelves. That was pretty normal, but that wasn’t all there was.

The walls were covered in dogs.

Big dogs, small dogs, strange foreign dogs – their blank sepia faces stared down from faded photographs, each in a brown frame. In one corner of the room there was a stuffed beagle in a glass case, its droopy ears and patchy fur serving to make it look even more depressed than beagles do when they’re alive.

The most bizarre sight was a dachshund, stretched out in front of the small window at the back of the office. It appeared to be being used as a draught excluder.

Strange, I thought, that someone with a name like Fox would like dogs so much.

“Stuffed dogs, Miss?” I wondered aloud.

“Can’t stand the things. I like to see them dead,” replied Miss Fox.

She pointed a long finger at a nearby chair until I got the hint and sat down on it.

“Now, Scarlet—”

“Ivy,” I corrected automatically.

She loomed over me like an angry black cloud. “I think you have misunderstood, Miss Grey. Did you not read my letter?”

Her letter? “I-I thought it was from the headmaster.”

She shook her head. “Mr Bartholomew has taken a leave of absence, and I am in charge while he’s away. Now, answer the question. Did you read it?”

“Yes. It said I was to take a place at the school … my sister’s place.”

Miss Fox walked around me and sat down in the leather chair that accompanied her desk. “Precisely. You will replace her.”

Something in the way she said it made me pause. “What do you mean, replace her, Miss?”

“I mean what I say,” she said. “You will replace her. You will become her.”

“Silence!” she shouted, slamming her fist down on her desk like an auctioneer’s gavel. “Scarlet’s place needs to be filled, and it is fortuitous that we have someone to fill it. We shall not have the good name of Rookwood School tarnished by unfortunate circumstances. We’ve put the absence before summer down to a bout of influenza, which you, Scarlet,” she looked at me pointedly, “have recovered from well.”

I was lost, reeling, and the room span around me. Perhaps this was a nightmare, and in reality I was in a tormented sleep back at my aunt’s house.

“But …” I protested. “You didn’t accept me for the scholarship! Only Scarlet passed the entrance exam.” I had never forgiven myself for that. I’d been up all of the previous night fretting about it, and I was sure I hadn’t studied enough.

“That is irrelevant, child. The fees are already paid. You will take your sister’s place for the sake of the greater good. From now on, you are Scarlet. Ivy might not have passed the entrance exam, but you did.”

I wanted to shout at her, but my lips were quivering and my breathing was shallow and panicked. “P-please, why do I have to do this?”

She held out a finger to silence me, the tip of her nail long and sharp.

“It does not concern you. These are adult matters, and we shall deal with them as we see fit. You don’t want to trouble the other pupils with this, do you?” She leant back and looked away from me.

“D-does my father know about this, Miss?” If everyone at the school was clueless, I hoped there was a chance that Father had been deceived as well.

My hopes were shattered when she replied, “Of course he does. We have his full permission. He understands that it’s the best way. Now,” she continued, “we’ve kept your room for you. Breakfast is at seven thirty.” She started tapping her fountain pen, and talking in a flat voice as though she were reading from an invisible blackboard. “Lessons start at nine.” Tap. “The matron’s office is at the end of our corridor.” Tap. “No loitering in the hallways.” Tap tap. “Lights out at nine o’clock …”

I should have been listening to the rules, but I couldn’t help being distracted by the items on Miss Fox’s desk – a lamp, a telephone, an inkwell, an ivory paperweight, a chequebook, a small golden pill-box and – oh no – a stuffed Chihuahua with a mouth full of pens.

“Pay attention, girl!”

My eyes darted back up. “Yes, Miss Fox,” I replied.

Miss Fox gave an exasperated sigh. “Here, take this –” she handed me a map and a list of the school rules. “Remember, you are Scarlet now. There is no more Ivy.”

She got up from the chair quickly, and waved at me to follow her.

It’s quite a thing to be told that you don’t exist any more. It took me a moment to stand, my legs were shaking so much.

I felt like one of the sad dogs on Miss Fox’s walls. Their glassy gazes penetrated my back as I walked out of the office, trying to leave Ivy Grey behind.

I trailed after Miss Fox, along the corridors and up some dark, claustrophobic stairs to the first floor. The walls were lined with regimental rows of little green doors with numbers pinned on. We stopped at one bearing the number thirteen. Of course, Scarlet’s favourite number. She laughed in the face of bad luck.

Miss Fox unlocked the door, thrust the labelled key back into the depths of her dress and left me standing in the corridor with nothing but a “get changed, girl” over her shoulder. The door was left swinging uncertainly on its hinges, and I peered inside with trepidation.

The dorm room was not unlike our bedroom at home, with two iron beds standing side by side.

In my mind, I saw Scarlet dashing in, bouncing on the mattress and untucking the bed sheets – she always said it made her feel like she was in a sarcophagus if they were too tight. She would blow a dark lock of hair from her eyes and tell me to stop looking so gormless and bring in our bags.

I stared down at my feet. There was just the one bag there, its sides slumping on the hard wooden floor.

Shaking my head, I picked it up and walked into the room, the ghost of Scarlet evaporating from my mind. I had to calm down, to pull myself together.

Sort out your room. Unpack your things. Don’t forget to breathe!

Out of habit, I immediately went for the bed on the left, before realising that Scarlet would have gone for the right. I had no idea if anyone would notice such things, but I dutifully crossed to the other bed, set down my bag and looked around.

The whitewashed room contained a big oak wardrobe, a wobbly chest of drawers and a dressing table with a chipped mirror. I caught sight of myself in it. Scarlet and I had the same dark hair, same pale skin, same small features like a child’s doll. Only on her it had always seemed pretty. It just made me look lost and sad.

“Scarlet,” I whispered. I stepped forward and held my hand out towards the mirror. When we were younger we used to stand either side of the downstairs windows and copy each other’s movements, pretending to be reflections. I would always do it backwards by accident, and she would collapse in fits of laughter. Yet now, as I waved my hand at the mirror, the image in the glass followed it exactly.

My head hurt.

In one corner of the room there was a washbasin with a sink and plain porcelain jug, with white flannels laid out next to it. Even though this room had belonged to Scarlet in the previous year, there was no sign of her.

I began to wonder what they had done with all her possessions. If they weren’t here, where were they? Where were her clothes and her books? Where was …

Her diary.

When we were little, she always showed me the contents of her diary. Sometimes she would let me write in it too. A new one every year. She would fill it with drawings of us, identical stick figures living in a gingerbread cottage with the evil stepmother. But as we got older she became more secretive, always hiding it. Not that I would have read it. If there were thoughts in there that she couldn’t share with me, her twin, I didn’t want to know them.

Scarlet’s precious diary could have been destroyed or lost or tossed away by a maid, and that thought made me shudder. But there was a small chance that Scarlet had hidden it too well for it to be found.

And if it was still here – all that was left of my sister – I desperately wanted it.

The wardrobe, I thought. It was always one of her favoured hiding places. I dashed over and flung its doors wide open, coughing at the musty smell of mothballs.

The only thing it contained was a single uniform, neatly folded over a hanger – a white long-sleeved blouse, a black pleated dress and a purple striped tie with the Rookwood crest on the end and a pair of matching stockings tucked underneath. I held the uniform up against me; it was exactly my size.

Scarlet’s uniform.

I stood still for a few moments. I was being foolish. They were only clothes. Scarlet and I shared clothes all the time. But now she was gone, and it wasn’t Scarlet’s uniform any more, it was mine. And that scared me.

I carefully laid out the uniform on the opposite bed and continued my search. The base of the wardrobe was lined with old newspaper and I peeled up the yellowing sheets, my nose wrinkling.

Nothing.

I stood on tiptoe and felt around on the top shelf – yet more nothing, unless you counted the dust.

I tried tugging at each of the drawers of the chest in turn. Several of them stuck and I held my breath, willing the diary to be inside. But each time I managed to get one open, I was faced with an empty drawer. Scarlet’s belongings may have been worthless to the school, but they weren’t to me. I knew that Scarlet had our mother’s silver-backed hairbrush – engraved with her initials, E.G. – as I had her pearls. Where could that be?

I fell on to my hands and knees and peered beneath the beds, but all I could see was an expanse of threadbare carpet. I tried picking at threads to see if it would come loose, hoping for a secret compartment under the floorboards, but it was well stuck down. Useless. I felt like crying.

I stood up and went over to the bed and threw myself down on to the uncomfortable mattress. Scarlet could have hidden her diary anywhere. Or maybe it had already been found, and destroyed …

Then – wait – I could feel something. There was a peculiar lump in the mattress. It was something hard and pointy. I shuffled my weight around, hoping that I wasn’t imagining it. No, there was definitely something there.

I jumped up, ran to the door and checked the corridor for teachers. It was silent, empty. I prayed that Miss Fox wouldn’t return any time soon.

Certain that no one was coming, I pulled off the grey blankets and bed sheets, throwing them into a heap on the floor. I ran my hand over the bare mattress, and I could still feel the lump. But there was no way to get to it. Or was there?

I got down on the floor and lay on my back, pulling myself right under the bed until I could see through the metal slats. It was dusty, and I had to resist a strong urge to sneeze.

And then I saw the hole. It was a long narrow slit cut into the material, maybe with a knife. The perfect size for a diary.

I pushed my hand into the mattress. Feathers and pieces of cotton stuffing scattered around my head and tickled my eyes as the coiled springs scraped against my skin. Then I could feel something else! It was hard and worn, maybe leather, and the tips of my fingers were just touching it.

My hand sunk in further, and I ignored the dust, the scraping, until …

There it was. I wrenched it out by the corner, and I clutched the little book to my chest, my heart pounding beneath it.

Scarlet’s diary.

They hadn’t found it. There was a piece of my sister waiting for me after all.

I wriggled my way out from under the bed and hastily tried in vain to brush myself off. Then I sat up, leaning against the cold frame, and stared at the book in my hands. It was brown and shiny, and the letters ‘SG’ had been carefully scored into the cover.

It looked as though half the pages had been torn out, but some of it was still intact. Hardly daring to breathe, I undid the leather strap, and turned to the first page that remained:

Ivy, I pray that it’s you reading this.

And if you are, well, I suppose you’re the new me …

You will be fine, as long as you remember me. It’s just acting, like we always said we would do. Only you’ll be playing my part.

Don’t pay too much attention in class. Don’t wear your uniform too neatly. Stay away from Penny. Don’t get on the wrong side of the Fox … you don’t know what she’s capable of. Don’t be as wet as you usually are – just look in the mirror, remember you’re trying to be me.

And Ivy, I give you full permission to read my diary – in fact, you MUST!

I stuffed the diary into my pillowcase, my heart racing. This was madness.

How could Scarlet possibly have known this would happen? She’d said I had to go along with the deception, and it seemed I had no choice but to do as she said. I shuddered at the thought of disobeying Miss Fox, too.

I couldn’t believe the web of lies I’d found myself in. All to escape shame for the school, to stop the other pupils from panicking about the ‘unfortunate circumstances’.

Who could I turn to?

Aunt Phoebe.

Of course! I ran to my bag and pulled out a pen, paper and ink. I flattened out the sheet on the dressing table and hastily scrawled:

Dear Aunt Phoebe,

Help! This has all been a huge mistake. I don’t know what’s going on here but they want me to pretend to be Scarlet. This can’t be right. I’ve found her diary, and somehow she knew this would happen. Something terrible is going on here.

Could you come and get me? Or tell Father? Please, this is important!

Ivy

I folded the letter into an envelope and wrote Aunt Phoebe’s address and URGENT in big letters.

But then, almost immediately, my excitement began to fade. How exactly was I going to send a letter? I didn’t have a stamp, nor did I know where to find a post office. If pupils needed to send letters from the school, they probably had to give them to a teacher. And if Miss Fox got hold of it, well …

That was a chance I couldn’t take. I had to trust Scarlet’s words. They were all I had left.

I forced myself to change into her uniform. The fabric was scratchy and didn’t smell like her at all. I looked in the mirror, but something was wrong … I loosened the tie, tugged on the hem of the dress and pulled the stockings up unevenly – there, not too neat.

Once I was dressed, I unpacked my few possessions before remaking Scarlet’s – my – bed, and finally collapsed on it, exhausted. But as my eyelids began to drift shut, I noticed a shadow fall across the room.

“Hello,” said the shadow.

I looked up. The girl barely filled the doorway. She was small and so mousy that she looked like she might beg for cheese at any moment.

I was about to offer an equally timid “hello” in reply, but then I remembered. I had to be Scarlet now …

“Hello!” I said, jumping up from the bed and forcing a cheery smile on to my face.

The mousy girl took a small step backwards. “Um, good afternoon. MynameisAriadneI’mnew.”

“Sorry?”

The girl inhaled a long, deep breath. “My name is Ariadne. Ariadne Elizabeth Gwendolyn Flitworth.”

“Oh … um, sorry,” I said, wincing.

“It’s okay, I’m used to it,” Ariadne sighed. She held out a small hand, nails bitten to extinction.

I looked at it for a second, and then shook it with nervous enthusiasm. “My name is Iv— Scarlet. Nice to meet you.” Oh dear, I thought, as I unhooked my hand from hers. I’m not very good at this.

Ariadne stooped to pick up her luggage, a little convoy of suitcases trailing after her. I watched her pick up each one and gingerly lift it over to her side of the room. I didn’t think to offer any help. It seemed like some kind of strange ritual.

“Are you new as well?” Ariadne suddenly asked.

“Me? Oh no,” I replied, my mind racing. “I was here last year.”

Ariadne looked around the bare room curiously, so I babbled on.

“Well, I was quite ill for a while. Some kind of flu, they said. Had to take all my things back home. They, erm, didn’t want everyone else to catch it.”

“Oh, of course,” said Ariadne, tucking strands of mousy hair behind her ears as she shuffled back and forth. “My father decided to send me here, because he had to go away on important business.” She didn’t say this in a proud or boastful way – more like repeating something she had heard many times. She finished laying out her suitcases and turned to face me, blowing a stray hair out of her face. “Um, I don’t suppose you could show me where the lavatories are?”

Oh good grief. I could hardly say that I had forgotten where the lavatories were. I hadn’t even looked at the map yet and I couldn’t remember seeing any signs on my way through the school either, but surely there would be some on this floor.

Ariadne was still staring at me so I quickly said, “Of course, they’re just … down here,” and motioned for her to go out into the corridor. As I followed, I glanced back at the bed, checking that the diary was fully concealed in my pillowcase.