Полная версия

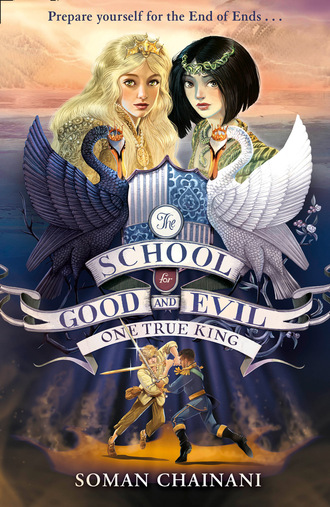

The School for Good and Evil

“Betty wasn’t taken,” Jacinda replied bitterly. “Another from Jaunt Jolie was kidnapped instead. This stultifying Beatrix girl who kept trying to be Betty’s friend, hoping it would ingratiate her in royal circles. But it’s all worked out in the end. Betty doesn’t need that school or the Storian. She’s found her own way to tell tales . . .”

“Aren’t you glad you burned your ring, then? If Betty doesn’t need the school or Storian, the rest of the Woods shouldn’t either,” quipped Sophie brightly, without a clue what she was saying.

The queen searched Sophie’s face. “Something’s not right with you,” she said quietly. “Tell me what’s going on. Even if those two witches are listening. I’ll take you to Jaunt Jolie. My Knights of the Eleven are fierce warriors and will keep you safe. And I have the ear of other leaders, Good and Evil. I have the power to protect you, Sophie.”

Jacinda looked back at the Mistral Sisters, as if expecting them to revolt or attack, but Alpa and Omeida said nothing, their hands fidgeting over their notebooks.

“Would you like a rum baba?” Sophie offered, on cue, holding out a cream-topped cake. “The new chef here is marvelous.”

“Didn’t know you were one to eat pastries,” the queen said tartly. “And it looks soggy and ill-made.” Jacinda locked eyes with Sophie. “I saw you at Tedros’ execution. I saw you and your Dean. I know whose side you’re really on.”

Sophie’s mind went stiff, the script aborted.

Behind the queen, the Mistral Sisters mirrored her pause.

“Me and the Dean?” Sophie asked, using her own words now. “Which Dean? What execution? I’m sorry . . . I don’t know what you’re talking about . . .”

The queen stared into the void of her gaze. “What’s happened to you?” she whispered, clasping Sophie’s wrist. “Why are you here instead of with Agatha?”

The warmth of touch.

The comfort of skin.

The sound of a name.

Agatha.

It slashed through the fog of Sophie’s mind like a lightning bolt to a lake.

Scrolls should not fall from the sky.

Scrolls should not fall from the sky.

Scrolls should not fall from the sky.

She saw the Mistral Sisters’ hands moving again, their faces tight, but Sophie was already short-circuiting the script.

“I’m feeling a bit ill,” said Sophie, standing up—

As she did, she knocked over the queen’s purse, which fell to the floor. “Oopsy,” said Sophie, reaching for it, only to punt it farther under the couch.

“Let me—” the queen started.

“I’ve got it,” said Sophie, already on her knees, reaching beneath the couch. “I certainly gave it a good kick . . . oh, here it is . . .” She stood and handed the purse back to the queen. “My advisors will see you out.” Sophie smiled at the Mistral Sisters, who looked more at ease now, as if Sophie had steered things back on track.

Jaunt Jolie’s queen studied Sophie one last time. “I wish . . .” She shook her head, trying to finish the thought—

Sophie kissed her on the cheek. “Thank you,” she whispered.

Then before anyone could say another word, the princess ushered herself back to her chambers, like a good little girl.

SOMETHING WAS INSIDE her head.

Something was controlling this pain.

Sophie had figured it out while sitting with the queen. First, there were those sisters, pretending to take notes. But every time they moved their hands, she lost control, someone else’s words coming out of her mouth, someone else’s thoughts usurping her mind. And if she tried to reclaim her thoughts, to think for herself, the pain came to hurt her.

Yet the pain attacked even when the Mistrals weren’t there. She could feel it now, slithering around her mind, waiting to strike.

Which meant the Mistrals might be able to control the pain . . .

But they weren’t its source.

The source was her head. Inside her head.

She didn’t yet know what was causing this pain, exactly. But she knew how to keep it at bay . . .

Don’t think.

So rather than thinking about the scroll in her fist, Sophie focused on the sounds of her feet: plip, plop, plip, plop, like the patter of rain, pulling her towards her chamber. Her white dress itched at her skin, surely suspecting something, but the dress stopped short of anything more as she slipped into her sun-drenched room and closed the door.

Quickly she tried to lock it, but the latch was broken. Her fault, of course. She’d burned through it to leave this room. Already her head was starting to throb harder, sensing mischief afoot.

She could hear footsteps coming down the hall.

Voices growing closer.

But then something strange happened.

A ribbon of white lace fluttered off her dress, fully alive. For a moment, Sophie thought it might attack her: this dress, which had a mind of its own. Instead, it slid through the broken lock and morphed into a white-stone bolt, jamming the door.

There was no time to think about why the dress was helping her.

The pain was already coming like an alarm.

Sophie flung open her fist, yanking the crumpled scroll out and matting it against a mirror on the wall, the bold, black ink slick in the sunlight—

So it begins, the first test arrives

Two kings race to stay alive

For a king cannot rule if he is dead

Or lead a kingdom without his head

But once upon a time, a man came to my court

Who gave up his head, just for sport

He wanted one thing, this headless knave

Tried to claim it and dug his grave

What did he want? Only my true heir will know

Now go and find it, where wizard trees grow!

Sophie couldn’t make any sense of it, not with her head about to pop like a balloon. Headless knights . . . wizard trees . . . ? The pain intensified, about to rip open her brain. She shoved the scroll into her pocket. It had to mean something. Something the pain didn’t want her to figure out—

Loud knocks attacked the door.

“Sophie!” Alpa said.

Hands jostled the lock, blocked by the ribbon of stone.

“Don’t do anything stupid!” Omeida harassed. “The king will know! He’ll see you! Wherever he is, he’ll come back and punish you!”

Sophie stared at the door, pain blotting out all thoughts but one.

“See” me?

Fists pummeled harder, but the stone held tight.

“Open this door!” Alpa demanded.

How can the king see me if he isn’t here? Sophie thought. Unless . . .

She peered at the scroll’s poem, flattened against the mirror.

Then, slowly, her gaze shifted to her reflection.

She heard guards coming now, the sisters ordering them to bash down the door . . . but Sophie was lost in her own eyes, studying her electric-green irises and big black pupils, the pain cleaving through her head, harder, angrier, as if it knew she was getting close. She couldn’t breathe, her mind impaled from every direction, her vision dotting with lights, her body seconds from passing out. But Sophie didn’t yield, glaring into the gems of her eyes, mining deeper, deeper, searching the darkness and light for something that wasn’t hers . . . until at last she found them.

Hiding like two snakes in a hole.

Guards bludgeoned the door with axes and clubs, the wood splintering.

Sophie had already lit her finger.

Pink glow reflected in her pupils like a torch in a cave.

She could hear their screams, the scaly eels, as they stabbed harder and harder behind her eyes, trying to regain control.

But the truth was in her sights now. Pain had become pleasure.

Sophie raised her finger and slipped it into her ear.

She grinned in the mirror like a devil facing itself.

This is going to hurt.

STONE SHATTERED IN the lock.

The door burst open, guards and Mistrals coming through.

A breeze sifted through the room, rippling across the blood-soaked curtains, the window wide open.

On the windowsill lay two scims crushed to filth.

But it was outside where the real message had been left.

Dripped in crimson across the white snow of scrolls, across the white dresses of maids, lying stunned by a spell.

Five bloody words.

The remnants of a princess.

The warning of a witch.

ALL OF YOU WILL DIE

TEDROS

Mahameep

“Your first test to become king . . . ,” said Hort, mouth full of cotton candy, “and you don’t know what it means?”

Tedros ignored him, kicking away scrolls that littered the cotton-candy grove just past the border of Sherwood Forest. He didn’t have to answer to the weasel. He didn’t have to answer to anyone. He was the heir. He was the king.

Yet he’d failed his first test before it had even begun.

The Green Knight. Why did it have to be about the Green Knight?

It was the one part of his dad’s history he’d never learned. On purpose. And his dad had known it.

Is that why Dad made it a test? To punish me?

Tedros shook it off, trying to find clues in the poem: “He wanted one thing, this headless knave . . .” “Tried to claim it and dug his grave . . .” “Now go and find it where wizard trees grow . . .”

He couldn’t focus, his thoughts spiraling—

What did the Green Knight want?

Why didn’t I ask Dad!

Does Japeth know?

Suppose he finishes before me? Is he already on to the second test? What if I’m too late—

A hand squeezed his.

Tedros looked up at Agatha, her hair dotted with blue and pink cotton candy.

“I’m sure Japeth doesn’t have the answer either,” his princess assured, her lips dusted with sugar. “How could he?”

“Well, we can’t just loaf around the Woods until I figure it out,” said Tedros, watching Hort and Nicola pluck trees and feed each other candy. “This forest is the path into Pifflepaff Hills. Where the Living Library is. We need to go to my dad’s archive there. It’s the only place where I can find out what the Green Knight wanted.”

“Tedros, we decided it’s too dangerous—”

“You decided. And it’s more dangerous for me to lose the first test!” said Tedros. “If Japeth doesn’t know the answer, the Living Library is the first place he’ll look. We should have gone when I suggested it instead of wasting time back there with Merry Men!”

“They were starving and homeless!” said Agatha. “We got them scraps from Beauty and the Feast and helped fix their houses. It was the Good thing to do.”

“Even I know that and I’m Evil,” Hort said behind them, mouth stained blue.

“We’re going to the Library. My orders,” Tedros said firmly, walking ahead.

He glanced up at school fairies tracking him from above, keeping a lookout over sugar-spun trees, while Tinkerbell squeaked at any who snuck down for a bite. Behind him, he could hear Agatha reassuring his mother that she would protect her prince, no matter how dangerous the new plan was.

Having a princess wasn’t supposed to be like this, Tedros thought. In all the stories he knew, princes protected their princesses. Princes were in charge and princesses followed. Yes, Agatha was a rebel, which is why he loved her. But sometimes he wished she was less rebel and a little more princess, even if he felt like an ogre for thinking it. Tedros flung aside a pink bough, barreling ahead. One thing was for sure: Agatha couldn’t win the first test for him. From here on out, they’d do things his way.

A short while later, the prince peeked between a last cluster of sweet-cotton branches.

The Pifflepaff Pavilion was painted pink and blue and nothing in between. There were blue “boy” shops—the Virile Vintner, the Hardy Folk Furriers, the Handsome Barber—and there were pink “girl” shops: Silkmaid’s Stockings, the Good Lady’s Bookshop, Ingenue’s Combs & Brushes. In the morning rush, men in blue stayed apart from girls in pink, including the pink-clad sweepers, who cleaned the pavilion of leftover scrolls. (Tedros’ dad had left no kingdom untouched in announcing the first test.) Then there were the trees dotting the streets, like the ones in the forest, blooming with bell-shaped tufts of cotton candy, the trees either blue or pink, from which only the appropriate sex could eat. Pifflepaffers tore off candy as they walked, men inhaling blue, women sucking on pink, as if they lived on nothing but their assigned clouds of color. There was no crossing of lines, no blurring of boundaries. Boys were boys and girls were girls. (Maybe it would rub off on Agatha, Tedros thought grouchily.)

At a coffee stand, a merchant had his blue stall divided into two sides: TEAM RHIAN and TEAM TEDROS, hawking themed drinks for each. Team Rhian’s side offered a Lion Latte (turmeric, cashew milk, cloves), a Golden Lionsmane (horchata, chocolate ganache), and the Winner’s Elixir (espresso, maca root, and honey) . . . while Team Tedros’ side sold a Snake Tongue (matcha powder, hot oat milk, ghee), a Cold Storian (iced coffee, cinnamon), and a Headless Prince (hazelnut, mocha, goat milk). The Rhian aisle was packed with men making orders, picking up drinks, catching up with friends. The Tedros table was deserted. “Who Will Win the Tournament?” read two tip jars, one with Rhian’s name, overflowing with copper and silver coins, the other with Tedros’ name, toting a few farthings.

Tedros’ blood flowed hot.

The Woods thought he had no chance.

Even though Excalibur had returned to the stone. Even though his father spoke from the grave and gave him a claim. These people still thought he would lose.

Why?

Because they’d seen Rhian pull the sword from the stone, while Tedros failed. Because they’d seen Rhian quell attacks on their kingdoms, while Tedros failed. Because Rhian’s pen told them what they wanted to hear, while the pen Tedros fought for told them the truth, even if it hurt. All of it was a Snake’s tricks, but the people didn’t know that. That’s why no one was betting on him. To the Woods, Tedros was a loser.

Which is why he had to win this first test.

Tedros peered harder through the trees.

The Living Library, a colossal acropolis, stood tall on a hill over the pavilion, its blue pillars and domed roof glowing in afternoon sun. On the stairs, flanking the entrance, were Pifflepaff guards, who despite their comical blue hats, shaped like muffin-tops, came armed with loaded crossbows, Lion badges over their hearts, and small pocket-mirrors, which each guard flashed at anyone who entered or exited the Library.

“Six guards,” said Tedros, turning to the others. “And they have Matchers.”

“Matchers?” asked Agatha.

“Living Library keeps ancestry files on every soul in the Woods,” Tedros explained. “Matchers track those going in and out, in case anyone tries to doctor or steal a file. Those mirrors tell the guards our names and what kingdom we’re from.”

“So if they’ll know who we are, how are we supposed to get inside?” Nicola asked.

Tedros glanced off. “Haven’t gotten that far.”

“And there’s no other way to figure out what the Green Knight wanted?” Nicola pressured, eyeing the scroll peeking out of the prince’s pocket. “There isn’t something you aren’t remembering or something your dad told you—”

“No, there isn’t,” Agatha defended, “otherwise we wouldn’t be here.”

“It’s his dad,” Hort snapped at Agatha, then pivoted to Guinevere. “And your husband. How can neither of you know a crucial part of King Arthur’s history? Even the village idiot knows the story of the Green Knight. Terrorized the Woods because he wanted something from King Arthur. Something secret. We know what happened to the Green Knight but no one ever found out what the secret was. Except Arthur, of course. And now you’re telling me you two don’t know what it was, either? How can King Arthur’s own family not know? Didn’t you talk to each other? Or have family dinners or holiday jaunts or the kinds of things Ever families are supposed to have that make them feel so superior to Never ones? If it was my dad, you bet your bottom he woulda told me what the Knight was after, even if it was a secret.”

Guinevere grimaced. “I wasn’t at the castle when the Green Knight came.”

“So much for you being a ‘resource’ on Arthur,” Hort scorned, then glared at Tedros. “And your excuse?”

“He doesn’t have to excuse anything—” Agatha started.

“Yes, I do,” said Tedros, cutting her off.

He needed to say it out loud.

The reason his dad chose this as the first test.

“The Green Knight came in the weeks after my mother ran off with Lancelot,” the prince explained. “I’d stopped talking to Dad. At first, I held him as responsible as I’d held her. For letting her leave. For not keeping her happy. For breaking up our family.” He looked at Guinevere, who struggled to hold his gaze. “Eventually I started talking to him again. And only after he came back from defeating the Knight. But we never spoke about his victory. It was a great feat, of course. He tried to bring it up again and again, baiting me to ask the details. Eager to share what happened. And I wanted to know. I wanted him to tell me what the Green Knight came for. But I never did ask. It was my way of punishing him, reminding him that Mother was gone and it was his fault. I wouldn’t be the son he could confide in. Not anymore. That’s why he made this the first test. Because I failed it when he was alive. Because I chose anger and pride over forgiveness.”

Even Hort went quiet.

Tedros suddenly felt the chill of loneliness. Agatha and his friends could only take him so far. In the end, it was him that was on trial. His past. His present. His future.

“We can’t change what’s already happened. What matters is finding the answer now. What matters is winning the first test,” Agatha said briskly. Tedros knew that tone: whenever his princess felt helpless or scared, she grasped for control even more than usual. Agatha pushed past her prince and squinted out at the Library. “If the Green Knight was unfinished business between you and your dad, he would have left you the answers. And you’ve said all along those answers would be here. You’re right, Tedros. It doesn’t matter if it’s dangerous. We need to get past those guards.”

“And their Match things,” Nicola reminded.

“There’s no ‘we,’” Tedros corrected Agatha. “I’ll go alone.”

“I’m coming with you,” Agatha insisted.

“It’ll be impossible enough getting me past the guards. How can both of us get past them?” the prince argued.

“Same way I broke into Camelot’s dungeons. Same way Dovey freed us from the execution,” said Agatha. “With a distraction.”

“And my mother?” Tedros peppered. “Can’t just leave her in the middle of the Woods with the weasel and a first year—”

But Guinevere wasn’t paying attention.

She and Nicola were watching something else in the forest: a squirrel with a royal collar, carrying a round walnut in its mouth, huffing and puffing past trees, as if it had already come a long way.

The old queen and first year gave each other narrow looks.

“Actually, Nicola and I have other business to attend to,” Guinevere said.

“Mm-hmm,” said Nic.

The two of them went after the squirrel.

Hort blinked dumbly. “Well, if you’re going into the Library and they’re going after a rodent, what am I supposed to do—”

He turned to see the Tedros and Agatha staring right at him.

“Oh no,” said Hort.

AT THE LIBRARY entrance, there was a lull in the flow of patrons. A guard disguised a yawn, his crossbow limp at his side; a second picked his nose with one of his arrows; a third spied on pretty women with his Matcher—

A blast of blue glow shot it out of his hands, dashing it on the Library steps.

Another blast took out the next guard’s Matcher.

The guards looked up.

A blond-poufed boy with no shirt, no pants, and a cotton candy diaper leapt in front of them, wagging his bum—

“Singing, hey! Laddie, ho!

Laddie, laddie, ho, ho

Same old shanty,

Sing it front and back,

Ho, ho, laddie, laddie, hey!”

The boy waited for the guards to attack.

They gaped at him dumbly.

The boy cleared his throat.

This time, he tap-danced too.

“I’m a pirate captain

Hoo ha, hoo ha

My ship is named the PJ Frog

Hoo ha, hoo ha

With a lass named Nic and a friend named Soph,

Ho, ho, laddie, laddie, hey!”

The boy shimmied his hands. “Olé!”

Guards still didn’t move.

Hort frowned. “Fine.”

He burst out of his diaper into a seven-foot-tall, hairy man-wolf.

“Roar,” he said, half-heartedly.

The guards charged.

“Never fails,” Hort sighed, upending trees as he dragged the men on a chase.

Meanwhile, a boy and girl hurried up the blue library steps, keeping their heads down. Tedros had smeared his shirt with cotton candy, giving it a splotchy blue tint, and hidden his blond locks under a mop of blue spun sugar, so he looked less like a prince and more a homeless elf. Agatha, for her part, had beaded her black gown with pink cotton candy and capped her hair with a towering hive of pink fluff. Together, they motored through the library doors, only to see a large sign.

BOYS ENTRANCE ONLY

By Law of Pifflepaff Hills

“Separate but Equal”

“You’ve got to be kidding,” said Agatha.

But ahead, there was a line of blue-dressed men waiting to get past a librarian—an old goat name-tagged GOLEM—who was checking each entrant with a Matcher, affixing them with their own name tag and letting them through, before he turned his attention to the line of women coming from another entrance.

“I need to use the girls’ door,” Agatha whispered, heading back outside—

But now the Pifflepaff guards had returned to their posts, Hort’s werewolf nowhere in sight. Just as they were about to spot Agatha, Tedros yanked her into the boys’ line. He could see the men in line were glaring at her, cracking knuckles and curling fists.

“I know, right?” Tedros chuckled. “Seems like a girl . . . but you’d be surprised.”

Agatha frowned at him, but the men glared harder now, prowling towards her.

“Go ahead. Look for yourself,” the prince shrugged, offering Agatha up.

His princess gasped, about to clobber him, but the men had stopped in their tracks. They peered at Agatha, weighing Tedros’ offer. Then they shook their heads with a collective grunt and went back to their business.

“Told you to trust me,” Tedros whispered to his princess.

“Thanks for that,” Agatha snapped as they neared the goat, scanning and name-tagging more entrants, “but how we gonna get past him?”