Полная версия

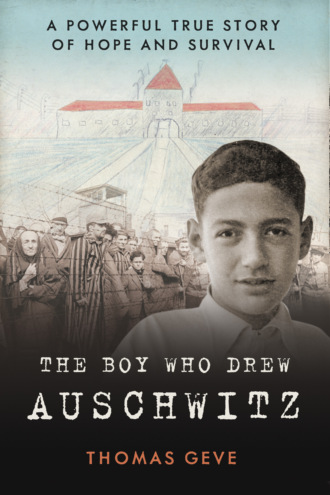

The Boy Who Drew Auschwitz

In 1936, aged six, I started at Beuthen’s Jewish school. Father, too, had once felt its cane, the punishment cellar and its strict Prussian discipline. He, likewise, had retaliated by scribbling and etching on the school’s benches.

Father’s teachers, already above retirement age, still taught there, and still could not afford anything more than white cheese sandwiches, which made them the subject of general ridicule. Aware of my family traditions, I tried to be a pleasant pupil, but never did more than was absolutely necessary.

We used both old textbooks and new Nazi textbooks. I remember Hitler’s birthday, 20 April, being a holiday. On this day, in accordance with some paragraph in the new educational laws, we gathered to hear recitations to the glory of the fatherland. The more insightful of our teachers, however, hinted that we would have no share in that glory.

My first day at school – Beuthen, 1936.

We learned that there was to be no equality. Our only weapon was pride. We wanted to compete with the new youth movements springing up across Germany. School outings turned into occasions to show off our disciplined marching, impressive singing and sporting prowess. But, one by one, these demonstrations were forbidden. Soon, we could not even retaliate to the stones being thrown at us in our schoolyard by the ‘Aryan’ boys outside. That would be a crime. Now we had become despised ‘Jew boys’. The only playground that remained safe for us was the park at the Jewish cemetery on Piekarska Strasse. We were actually glad to have a safe place to play in.

At my father’s urging, I joined a Zionist sports club, ‘Bar Kochba’.2 The training was strictly indoors, but the self-confidence it gave us was not so confined. There we learned about the principles of strength and heroism. Our newly acquired courage accompanied us everywhere.

One evening, a friend and I were making our way to the club and passed by the wintry synagogue square. We were greeted by a hail of snowballs. Then came the abusive insults. Behind the columns of the synagogue’s arcade, we caught glimpses of black Hitler Youth3 uniforms sported by lads who seemed to be about our age.

Pride momentarily gained the better of our obligation to be docile underlings, and we gave chase. Our perplexed opponents had not reckoned on the sudden fury that overtook us. I grabbed one of them, threw him onto the snow and hit him repeatedly. When he started yelling, I had to retreat. His friends were nowhere to be seen, and darkness shrouded our little adventure in secrecy. That was to be my first and last chance to hit back openly.

Soon I grew more inquisitive about the world I lived in. We boys sneaked away to visit nearby coalmines, factories and railway installations. Our young minds were thirsty for knowledge.

The glaring white blast furnaces, the endless turning wheels of the pitheads, the enormous slag dumps, the ore-filled trolleys gliding along via sagging overhead steel cables – everything was teeming with activity. Trains in particular fascinated me. The squeaking industrial rail lines and the big black locomotives that came in from afar and relieved their exhaustion by blowing off clouds of smelly steam. It was all waiting to be analysed by our young minds, inspiring us with a desire to understand life. The world was still to be discovered by us.

There was so much for us to explore, despite the restrictions that were enforced on us.

While we roamed the town, curious to discover, Beuthen’s Hitler Youth were drilled, marched and taught to sing praises to the glory of their Führer. Not all of them possessed the required mental strength for this training. Some, seeing their future predestined by authoritarian rules, retreated into a state of misery. Others, with less delicate minds, worried about flat feet, corns and blisters, for these were much more realistic obstacles for inclusion in the ‘master race’.

A few times a year, Beuthen’s streets would come alive with processions. On Ascension Day and Easter, Catholic clerics – masters of pomp and ceremony – would swing incense on elaborately decorated floats, and carry their main attraction, the bishop, under a gold embroidered canopy. And on May Day, Hitler’s substitute for the 1 May holiday, fairs and bandstands would decorate Beuthen, and festive national costumes celebrating industrial and agricultural achievements would be on full display.

In contrast to the joyful sounds and bright colours of celebratory street scenes, increasingly, black jackboots could be heard marching to the tune of sober martial music. The Brownshirts4 contrived a new kind of procession: the night-time torchlight parade. Some ended with non-believers, Jews or similarly oppressed people, being beaten up.

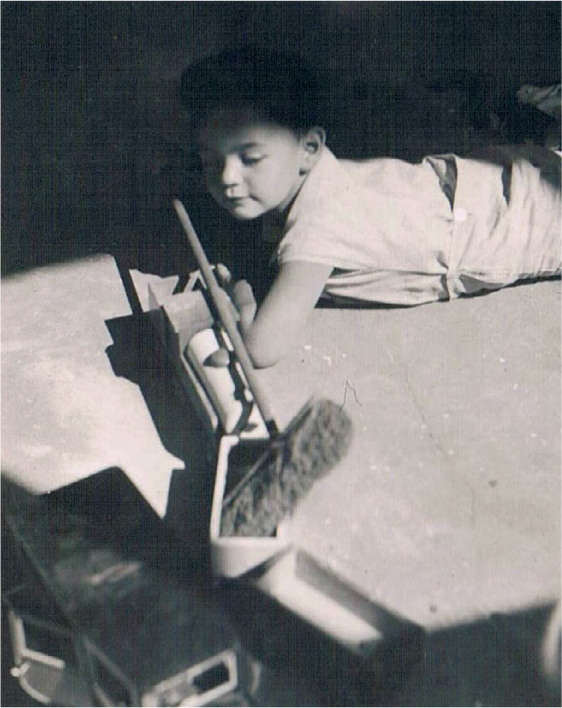

Playing with my Meccano.

My freedom was curtailed. I was ordered to stay home. There I watched these ‘shows’ from behind drawn curtains, with Mother explaining that these events were ‘not for our benefit’ and that I was to ‘avoid the streets and concentrate on indoor games’.

Unable to roam freely, I became more friendly with my school mates, inviting the more interesting ones home to play with my Meccano miniature railway set. Quickly, the family objected to my choice of friends.

‘Why must you bring these ill-mannered unkempt boys home?’ I was admonished. ‘Aren’t there enough respectable acquaintances of ours – doctors, lawyers, businessmen – whose children you could play with?’

But I was unconcerned with suitability or influence. My idea of having a good time demanded only new ideas, alertness, mutual respect and freedom. Thus, playmates chosen for me from good families never became good friends. Their knowledge of ‘the street’ was poor, their temperament was affected by their parents’ moods, and for every little thing they had to get permission from their maids.

Each year the festival of ‘Rejoicing with the Torah’5 was celebrated at our synagogue. Accompanied on the organ, children (dressed in their best suits and waving colourful flags) slowly followed the scrolls as they were carried around the temple. We were rewarded with the traditional handing out of sweets and chocolates.

Afterwards, we compared our treasures. My pockets were full, but I could see the disappointed faces of the other children. I was upset, as we should have all been rewarded.

Later, I asked my father about this, and his hesitant reply brought an unpleasant insight into my young mind that spoiled my fun. While most people gave generously to all the children, some people would single you out to take home their ‘visiting cards’ if your family had influence or social standing. Sweets. It seemed that Father was quite aware of who was distributing the chocolate bars or lollipops. Therefore, if you came from a family of have-nots, even a synagogue ceremony could make you aware of the fact.

One morning, the street underneath my window was humming with the noise of breaking glass, urgent footsteps and excited voices. It woke me up. Aware that it was time to get dressed for school, I got up and tugged at the belt of the roller shutter curtain. But to my surprise, it was only dawn. I peered over towards the pavement opposite our house.

One of the black Daimler cars that boys were so fond of was parked in front of the shoe shop. Our street was littered with shiny, black, brown and white boots, sandals and high-heeled women’s shoes and glass splinters. A team of uniformed Brownshirts were busy loading the car with all kinds of treasure. It was obviously a robbery.

Feeling rather like a successful detective, I ran to my parents’ room to tell them of this news. Visibly less glad about my discovery, Father phoned the neighbours. There seemed to be general confusion, with only one thing being certain: there would be no school that day.

I looked at my wall calendar. It was 9 November 19386 – and the world as our community knew it was about to change dramatically.

More reports came in throughout the day. Beuthen’s synagogue was burning. The town’s fire brigades refused to help as they were ‘busy guarding adjacent buildings’. Heaps of books were being thrown into bonfires on the streets. Jewish shops were being looted all over town. And hundreds of Beuthen’s Jews were being arrested.

Dismay and anxiety filled our building. We all assembled into one room, fully dressed and ready for an emergency, dreading the knock on the front door. Finally, the knock came. We opened the door and were face to face with a Brownshirt. His face was harsh and his staring eyes were narrow, hard and cold. His finger glided ominously down a lengthy, typewritten Gestapo list. When his finger stopped, he snarled out the name of an elderly Jew, a former tenant who had since moved elsewhere. Luckily, the Brownshirt was not interested in taking any of us along as a replacement.

Later, we learned that the synagogue had burned down completely and our school was closed for good.

Parents who could afford to do so sent their children away to the countryside, a temporary safe haven. I was sent to a Jewish children’s home at Obernick near Breslau, 220 kilometres north-west of Beuthen, for a month. Among its gardens and woods, we had the chance to explore nature. That was wonderful for me and it felt like paradise.

Most of the Jews in Beuthen who could emigrate did so.7 My father, a veteran of the First World War and well-known Zionist, planned to get us to England. From there we could reach Palestine, the land of Israel. But progress was slow, despite our growing desperation. A decision was made for me to move to Berlin at the beginning of 1939 to stay with my grandparents.

The world was not kind to refugees. People talked a lot about Birobizhan8 as a potential sanctuary from the persecution for European Jews, but few ever took it seriously. Polish Jews in Germany were being deported by force back to Poland. The Poles were no more eager to have them than the Germans were. ‘This can’t happen to us’ was the consensus among German Jews: ‘We are Germans.’

Rumours, an inevitable consequence of censorship in a totalitarian regime, abounded and kept circulating like some biased, hidden newspaper. We knew an ‘Aryan’9 who was a member of the Nazi Labour army, O.T.10 Unemployment had forced him to join this underpaid organisation to work on local road and canal construction projects.

Considering himself to be knowledgeable, he urged us to leave Germany as soon as possible. His predictions for the future – our future – seemed emphatically grim, possibly even uttered with a certain amount of malice.

The summer of 1939 saw my family leave Beuthen for good. Father left for England; Mother and I to my grandparents’ apartment in Berlin. We were planning to join him soon after. I tried to imagine what our new life would be like once we were reunited with him in England. But history had her own plan and in September of that year the Second World War broke out and all borders were shut. Mother and I stayed in Berlin.

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN 1939–40

Moving to Berlin, 1939.

Mother had been busy making arrangements for settling in Berlin, so I was once more left in the care of her sister Ruth, an art and English teacher. Auntie Ruth had all the qualities of a true friend. She was fun, interesting and always teeming with new ideas and progressive thinking. Ruth was an idol to her pupils.

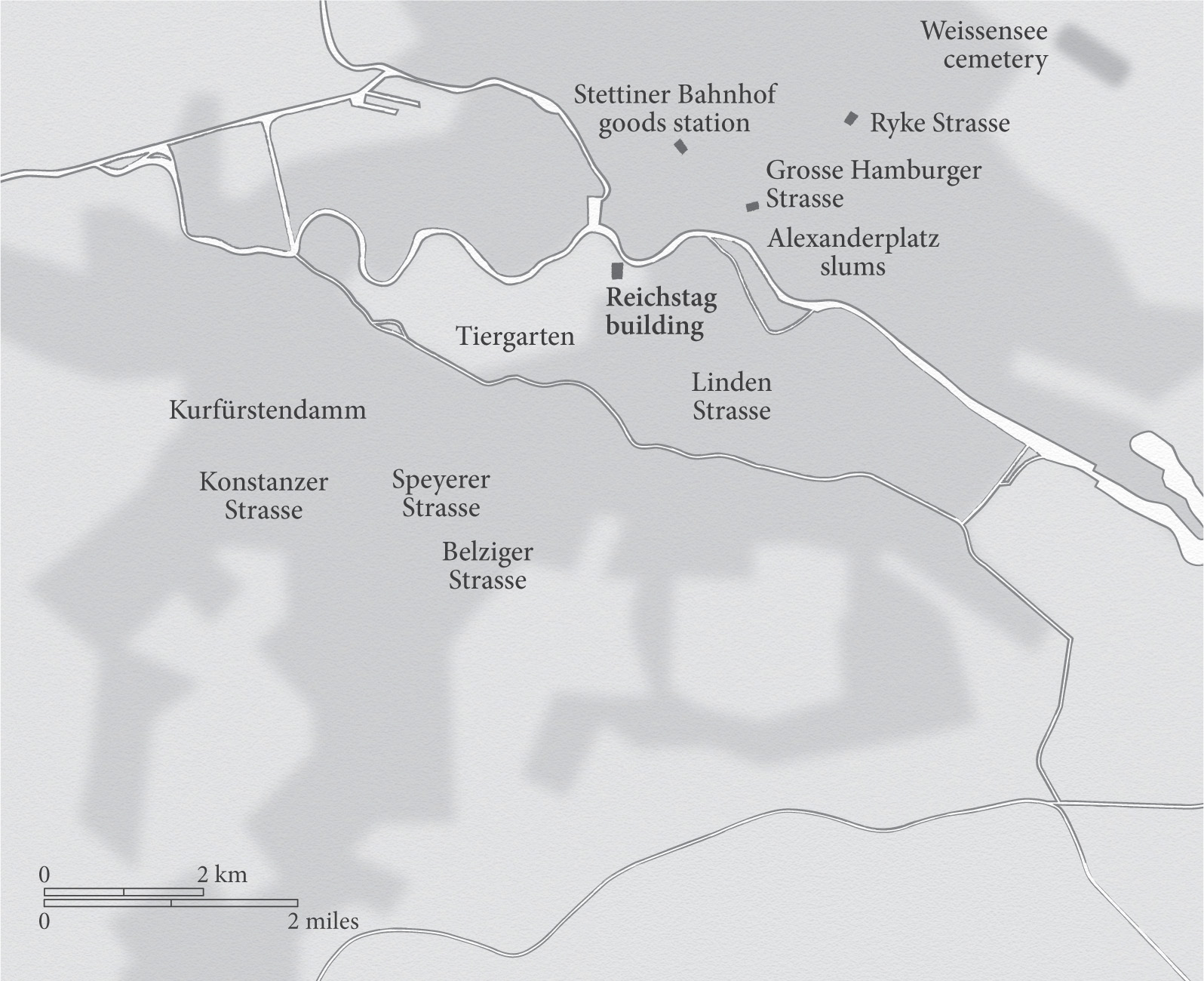

Auntie Ruth took me along to the Jewish school on Ryke Strasse in north Berlin, where she taught. My classmates there were real city children, conversant with the local slang, swank and swagger. At first, I was looked down upon as a country yokel, but soon they came to like my down-to-earth character, and eventually I became a fully-fledged Berliner. As I did so, my initial frightening impression of Berlin’s city life gave way to an understanding of its make-up.

The city’s routine began with the baker, the milkman and the newspaper boy doing their rounds. Later in the morning, the hawkers of brushes, shoe polish, flowers and the ragpicker would come. They all worked the streets of closely packed apartment buildings, which hugged each other for metropolitan warmth. Behind them, smaller buildings crowded around backyards. Their dirty brick walls reverberated with the sounds of city life: blaring radio sets, the beating of dusty carpets, crying children, squeaking staircases, twittering canaries and quarrelling couples.

For a while, the rise and reach of Hitler and National Socialism did not seem to matter; Berlin-life moved to its own rhythm and rules. One could not expect an occupant of a working-class tenement house to concern himself deeply with questions of race. He did not care whether the bugs invading his house in search of new feeding grounds had previously sucked Aryan blood or that of supposedly lesser human beings like Jews.

When war came in 1939, the changeover from peacetime seemed almost a technicality. Those who had made nationalism their business were overjoyed – Hitler and his henchmen had prepared Germany well.

Pro-war propaganda had not been defeated in 1918. On the contrary, the fact that peace had become possible had given it a new impetus. Rationing had begun in 1938, so now a few more items became scarce. Food, especially meat and vegetables, was harder to get. Mock air raids and trial blackouts made themselves such a nuisance that the real thing, expected to be less frequent, was greeted with some relief.

But Mother Krause, an archetypical Berlin housewife, was not so certain.

‘It’s an ill wind that blows no one any good,’ she sighed. ‘My old instinct tells me.’

The occasional howling of the air-raid siren brought her down to the damp, improvised cellar. There she shared the company of the seventy-odd neighbours who had their blankets, emergency rations, heavy suitcases, dogs and canaries.

Mother Krause had known my grandparents for many years, and she would not offend them. ‘My old instinct,’ she would mumble, ‘does not like Jews, but these don’t seem so bad.’

Children at the Ryke Strasse school in 1939, which I attended for a few months only that same year.

Our food became ersatz (substitute). Berlin’s bigger department stores like KaDeWe, worried by a lack of provisions, were advised to attract custom with elaborate shows, exploiting all the spoils and ideas from a conquered Europe.

Large shop windows were filled with reconstructions of scenes from Nazi films, including ‘Jud Süss’, a twisted, violently anti-Semitic story of a rich courtier; ‘Ohm Krüger’, an anti-British account of the Boer War; and a biographical feature on ‘Robert Koch’ that glorified German medicine.

The experience was different for Jews. They were issued special ration cards with little Js scribbled all over them. These cards prevented us from buying vegetables, meat, milk, chocolate and any special holiday treats that might have previously been allowed. It also meant that we could not buy clothes. We were allowed to shop at ‘approved shops’ only during the prescribed ‘non-Aryan shopping hour’ between 4 and 5 p.m. Anti-Jewish laws kept on coming in every two weeks, including one that stipulated that Jews could not sit on trams. If one was rich, the food problem was eased by the black market. If one was both wealthy and Germanic, high-class restaurants could be counted upon to provide a fair diet. Being neither, we could only hope for some help from better-qualified friends.

I turned 11 in 1940 and the time came for me to enter senior school. We were now a poor family and unable to pay fees, so I had to rely on scholarships. A mixed school on Grosse Hamburger Strasse was chosen for me.

The school had troubles of its own. First it was transferred to Kaiser Strasse, and then later to Linden Strasse. The authorities could not care less about a Jew’s place of learning, and still less about their feelings. Even the synagogue on Linden Strasse was now a grain store filled with hungry rats.

A classmate of mine, a half-Jew, had a sister at an Aryan school nearby. Some ridiculous court decision declared him a Jew but his sister a Christian. When they met in the street, they had to ignore each other in case someone saw them.

My friends and I amused ourselves with a number of hobbies.

We collected the figures sold to help finance the war. These included carved wooden dolls, and replicas of aeroplanes, guns and shells, which were sold and pinned on people’s lapels. They made for quite attractive toys. Every other month there were new models to choose from. To get them, my friends and I followed the example set by the street children of north Berlin. Whoever still wore these adornments on his lapel after collection week was asked politely to surrender them to us. This sport became so popular that passers-by even thought themselves subject to a new kind of recycling scheme.

We also collected children’s magazines. They were surprisingly free from the Nazi propaganda and given away at big confectionery stores. We got them by making a favourable impression on the salesgirl or, as a last resort, by buying a packet of pins.

My strangest delight, though, was compiling lists. Bombed-out buildings greatly fascinated me. All their intimate interiors could be seen, and each house had its own characteristic detail. My passion was to jot down in a book, the place, the date and the extent of the destruction.

When Mother found out about this, her stern rebuke made quite an impression on me. ‘What if you were caught? How would you prove that you are not a spy for the Allies?’

With an exciting war on, school seemed dull and pointless. Accordingly, I took to exploring Berlin’s streets. The school was an hour’s journey away, so at home my absence could easily be blamed on heavy traffic, air raids or extra lessons. Plus, the family allowed me ample freedom, so few questions were ever asked. I was now a street boy and blacked-out Berlin became familiar to me.

Books, cinemas and shows were not supposed to be enjoyed by non-Aryans, so it was useless asking for pocket money to pay for them. Instead, I visited exhibitions of captured spoils of war – a must for technically minded youngsters like me. I studied aeroplanes, inspected pilots’ seats and propellers, and ignored the notices warning non-Aryans to keep out.

Nor did I miss morale-boosting fairs during the summer of 1940, where Churchill’s dummy head could be shot off, and clockwork puppets, dollies and soldier boys danced to the tune of ‘Lily Marlene’ or ‘Wir fahren gegen Engelland’ (‘We’re going to take on England’). And I passed unnoticed along Friedrich Strasse, where the company of fleshy life-sized ‘dolls’, dressed in fur coats and the latest fashion from Paris, could be enjoyed for five marks.

My extensive explorations were made possible by the monthly subway tickets provided by the school, and a Hitler Youth uniform, without insignia, as a disguise. It was clearly dangerous for me as a Jew to wear this uniform, but I had little choice. Growing quickly out of my clothes and with no money to buy new ones, the only items of clothing I had were those given to me by a non-Jewish friend.

Once, I emerged from the subway station at Unter den Linden and was pushed straight into a huge parade. Had I backed out, it would have attracted attention, so I played along as an enthusiastic admirer. Peeping through the ranks of closely aligned guards, I had a good view.

Rolling slowly down the broad thoroughfare, accompanied by the noisy jubilation of the crowd, came open-topped black Daimlers. The leading car passed barely 10 yards ahead of me. Hundreds of hands shot up on cue to give the Nazi salute.

The adulation was for a dark-featured, rigid-looking man, with a strange moustache, who gazed ahead without emotion. This man was Adolf Hitler. Behind him followed the large form of Göring and other senior members from the German High Command, all of whom seemed equally unappreciative of the grand applause.

The traditional haunts of the German army and headquarters were in the area between Tiergarten, Potsdamer Platz and the Shell-Haus. I had the most unexpected access to this Nazi labyrinth thanks to a friend, whose mother was the mistress to a high-ranking officer. I was considered to be a well-bred and well-mannered companion, so he picked me out as the only classmate that could be honoured with an invitation to visit.

This was a dangerous world for me to walk into, but I was fascinated. There were field-grey cars lined up neatly between the numerous villas. Inside these buildings, teleprinters ticked relentlessly away, typewriters rattled and Prussians clicked their heels. Mobile radio stations hummed out words of war and there I was – a ‘Jew boy’ – walking freely and unimpeded.

Here I had my first proper glimpse of Hitler’s army, and it was undeniably intimidating and impressive. Pairs of jackbooted military police, with Roman-style polished metal plates on their breasts, stamped through the street. They didn’t bother with children like me. And neither did the colonel, who watched us playing chess in his garden.

I lived in Berlin from 1939 until 1943.

CHAPTER 3 BERLIN 1941–42

Towards the end of 1941, the Nazi government put up a formidable show of force. That September, Jews had been ordered to wear the six-pointed yellow Star of David.

The stars had to be stitched over the left breast on every piece of clothing. They had to be freely visible whenever and wherever Jews might encounter a non-Jew. Well-bred ladies assured us over cups of ersatz coffee that ‘Germany’s honour will never allow such an outrage. We are a civilised nation and can’t go back to the Middle Ages. People will protest in the street!’ But sadly, that prophecy did not come true.

When the first Stars of David appeared, some ridiculed the notion, while others mocked the wearers. There followed a period of indifference that gave way to feelings of annoyance at being constantly reminded by the yellow rag of shame. We went without it whenever there was a likelihood of not being recognised by informers.1 Under the light of the violet neon lamps that lit Berlin’s streets, the yellow stars looked blue. Even better for hiding them were the blacked-out side streets, and, as a last resort, one could carry a newspaper or a satchel pressed underneath the left arm and over one’s heart. An evening curfew for Jews was also sanctioned, but its enforcement seemed practically impossible. We generally ignored it despite the risks.

Soon, other labels joined the Star of David. There was P for Poles, and OST for Ukrainians. The decade-old signs forbidding entry to ‘Jews’ alone had to be taken down and revised. Corrected ones appeared. All public places, from a lone bench to spacious parks, from the telephone booth to the cinema, now displayed notices warning ‘non-Aryans’ to keep out. Some establishments striving to adhere strictly to Nazi law showcased signs that were more direct: ‘Entrance to dogs, Poles, Russians and Jews strictly forbidden!’

In 1942, Jewish schools closed. Each day fewer students had been attending school anyway. They were not necessarily playing truant; they may have been arrested or gone into hiding. The decree to close the schools came as a bit of a relief for me. Now, there was no more fear of being beaten up on the way home for being a ‘Jew boy’. Moreover, I did not believe in textbooks; I believed in technology and what I could see around me. I was able freely to explore Berlin and it opened my eyes and my mind to the wonders of technology and industrial invention.