Полная версия

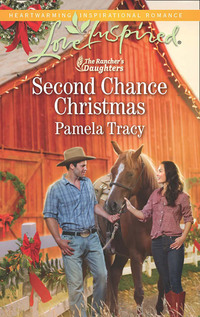

The Rancher's Daughters

Looking across the table at Timmy, he tried to decipher if the young boy showed any emotion at being abandoned. Not really. Then, Jesse looked at his mother and tried to see any hint of interest, grandparental pride, something.

Nothing.

“How’d Matilda find you?”

“Didn’t get around to asking,” Susan said. “And she didn’t bother telling.”

“Timmy,” Jesse said, “did you know Matilda, your mom, planned on dropping you off?”

The yellow crayon clutched between Timmy’s fingers was quickly becoming a nub. The little boy didn’t look from the gold-panning scene he was coloring.

“Do you know your mom’s phone number?” Jesse tried next.

“I’ve already asked him, at least twice a day. He hasn’t said a word. I don’t think he can talk. Anyway, she didn’t leave a phone number or previous address. Nothing except her car, some games and a bunch of clothes.” His mother picked up her fork and ate her food as if it had been a week since her last meal. She didn’t look at Timmy.

He’d felt that same parental disconnect during his childhood. Felt it now, at twenty-four years of age. He didn’t know the woman sitting across from him, felt no connection. When Jesse was very young, he hadn’t been allowed to call her “mother.” She’d passed him off as her younger brother because calling him her son might have discouraged boyfriends. The deception worked for a little while because she’d had him at fifteen. But as time passed, the drugs and hard living made her look even older than her actual age.

Matilda had dropped off their son and disappeared? Jesse had no history, nothing to go on. Where had they been living? Had Matilda tried to be a good mom? What had happened? He had all kinds of questions, but they were not ones he’d ask in front of the child. Already, though, he knew his mother was telling the truth. Matilda had abandoned Timmy the same way Matilda had abandoned Jesse. And the same way Jesse’s mother used to abandon him.

This wasn’t how he’d pictured his first day of freedom. Jesse wanted to come to town, meet his employer and join productive society: the working world. He needed time to figure out his future.

He’d need a lifetime to figure out what to do with Timmy.

“You need to eat,” his mother advised him. “I, for one, am starved.”

Any appetite Jesse might have had disappeared with the words “Meet your son.”

The waitress, way too happy, came over and refilled Jesse’s water glass. She scooted Timmy’s milk glass closer to him as if to hint “Drink this. It does a body good.” If she noticed something amiss, she didn’t let it show.

She walked away from them to chat with the blonde seated in the corner. When Jesse looked over, he noticed the woman was watching him, her expression guarded and somewhat disdainful. He got the feeling she knew not only where he came from and what he’d done but had already made up her mind that his future would be just as bleak. The look on her face was the same one the guard had given him before saying he’d see him soon. Yet for all that, she was a pretty thing, all long blond hair and Westerny: clean and soft.

Clean and soft weren’t the words most females wanted to hear, but to a man fresh out of prison, they were powerful. She looked like someone well taken care of.

Someone smart enough to stay away from him.

Her cheeks colored about the time Jesse looked away. He had other things to focus on, like a newly discovered son.

He took the first bite of his hamburger, washing it down with a swig of water, and asked, “Did Matilda say why she dropped Timmy off? Was she in some kind of trouble? I mean, did she say when she’d be back?”

His mother rolled her eyes. “She didn’t even say she was leaving before she climbed out the bathroom window without taking her kid.”

Timmy didn’t act like he knew they were talking about him.

“And, you’ve had him how long?” Jesse asked.

“Nine days now.”

Jesse figured in those nine days, his mother had done more talking at the kid than to the kid. That was her style. Looking at Timmy, she said, “His mother left a twenty, but that didn’t last long. I’ve had to buy lots of extra food, stuff I normally don’t buy. Things like spaghetti, peanut butter, jelly and Pop-Tarts. Nothing in the car worth selling. Believe me, I looked. And then there’s the gas for driving him here.”

He knew exactly what his mother was telling him and took a deep breath. She wanted to be reimbursed. But what money could she honestly expect from a man who’d been out of jail for only a few hours? He was living on faith, but had no clue how faith could help Matilda, his mother or Timmy. Part of him wanted to pray; part of him wanted to run out of the restaurant. Instead, hating himself for what he couldn’t provide, he said, “You’ve come to the wrong man. Right now, I can barely help myself.”

“Not sure you’ll have a choice.”

If not for the generosity of Mike Hamm, he wouldn’t even have the clothes on his back. The prison chaplain had provided him with the pants and shirt, not wanting him to leave prison in state-provided denim blues.

“I don’t have anything to give,” he told his mother.

She didn’t respond. Instead, resignation on her face, she glanced out the restaurant window, looking like she wished she was miles away. He knew she wasn’t wishing to be any place in particular—just anywhere but where she was.

The boy watched, not uttering a word, ignoring Jesse’s attempts to ask him about age, school status and favorite things to do. The yellow crayon broke, and now Timmy colored with a dark blue crayon.

“Got a job lined up?” his mother finally asked after checking her watch for a third time.

“Yes.”

Susan gave a shrug and took the last bite of her meal. “That’s more than I can manage. Soon, though, things will be better. I’ve met a guy, a nice guy, and we’re heading for New Mexico. Maybe this time it will last.”

Jesse had never figured out what the “it” his mother talked about was. When he was young, he’d thought it meant love. As a teenager, he’d thought it meant monetary support. Now, as an ex-con, he figured it meant companionship and money.

His mother didn’t really understand the concept of love, so that couldn’t be it.

“He’s not crazy about the kid, I’ll tell you that,” Susan continued. As if cued, her cell phone sounded a rendition of “Free Bird.” She picked it up and looked at the number. “Oh, it’s him.” She answered with a “Hey,” then stood and said to Jesse, “Let me take this where I can hear.”

She headed to the front of the restaurant and stopped at the door. Before exiting, she said, “He’ll be excited that you and I met up.”

Somehow Jesse doubted it. In all his years, not one of Susan’s boyfriends had been excited about meeting Jesse. And certainly, meeting Jesse—fresh out of prison—with Timmy as collateral damage was more than any significant other could take.

Jesse turned his attention back to his meal. The food was better than anything he’d had in the past few years and he intended to enjoy it while he could—and enjoy the momentary silence before his mother returned.

* * *

Working at the ranch, being in charge of guest relations, Eva’d seen dysfunctional families up close and personal. As a matter of fact, she’d called the police a time or two, and once drove a woman all the way to California when her husband decided to end their marriage in the middle of their vacation.

Not fun.

She wasn’t sure how the woman who’d just sashayed from the restaurant was connected to Timmy’s father. He’d never spoken to her by name. She dressed young, but her face bore the lines of hard living. She’d introduced the boy as “your son” and not “our son.”

The man, on the other hand, didn’t look as rough—in part because he clearly had God in his life. Again, Eva felt a nudge of guilt. Last Sunday morning’s sermon had been about being judgmental. Sitting beside her father on the pew, Eva knew this was a trait she struggled with. At the front desk of the ranch, she often decided on personalities of people before they’d finished check-in.

She judged which parents were too easy on their offspring. She judged which family would prove to be good tippers and which would leave their rooms an absolute mess. She was often right—but she’d been wrong a time or two.

Maybe she’d misjudged the man across the restaurant.

Eva glanced out the window and watched as the woman passed the bench by the front door, quickly lit up a cigarette, and then headed alongside the building.

The phone call must be really private for her to go out back where the Dumpsters were located. Except...she’d already put away her phone.

Stop it, Eva told herself. This is ridiculous. Go back to your book. She reread the last paragraph, but she’d forgotten the storyline.

Outside, the woman walked up to a man on a motorcycle.

Feeling slightly ridiculous, Eva glared at the doors to the kitchen. The bill...Eva really needed her bill. She was worried, actually worried about the two males left behind. And she didn’t even know them! If the restaurant hadn’t been so empty and the family—at least the woman—so noisy, Eva wouldn’t be so curious.

At least curiosity wasn’t a sin.

Not in moderation.

The rev of the motorcycle engine sounded right outside. Eva sighed and gave up pretending that she wasn’t watching. Peering through the window, Eva watched as the woman took one last puff from a cigarette before throwing it to the ground. She seemed agitated.

She also seemed to know the man on the motorcycle. Well enough that she climbed on the seat and wrapped her arms around his leather jacket. And then, off they went.

Eva hoped she hadn’t just witnessed someone getting dumped, especially not a someone who’d just heard the words “Meet your son.”

None of my business, Eva reminded herself.

But she knew the woman hadn’t said goodbye. And she knew what it was like to wait for someone who had no intention of returning.

She glanced back at the two guys left in the restaurant. The little boy, Timmy, picked at his food, eating with his fingers, and making a mess of his face. The man pushed an extra napkin in his direction, but Timmy ignored it, coloring more vigorously in between bites of food. Then his crayon rolled toward the edge of the table, and when he moved to grab it, he knocked over his water glass. Water covered the page he’d been coloring. Timmy froze.

Eva knew that response. The kid expected some kind of punishment.

“It’s okay,” the man said, gently. “We’ve got plenty of napkins.”

Just then, Jane showed up with more. Timmy was an unyielding mannequin. He looked like he was barely breathing. The man literally had to scoot the boy’s chair out of the way so Jane could clean the table.

Eva looked out the window again. The motorcycle and its two riders were long gone.

Jane brought Timmy a new coloring sheet. “You want dessert?” she asked.

“No, my mother stepped outside to take a call,” the man said. “As soon as she returns, we’ll pay the bill and take off.”

So the woman was his mother. But if he waited for her to come back, they’d be waiting a long time. Eva waved Jane over.

“You need to tell him,” Eva whispered, “that his mother just took off on a motorcycle with some guy.”

Jane took a step back. “You’re kidding. I don’t want to tell him.”

“We can’t leave them waiting.”

“You tell him,” Jane said, and before Eva could stop her, she’d motioned for him to join them.

Eva watched as he glanced at his mother’s keys, at Timmy and then at the front door before joining them.

Eva should have left a twenty on the table and hightailed it from the restaurant. Then she wouldn’t have been in this uncomfortable position. She looked out the window again, hoping the woman would magically appear. “You’re waiting for your friend to come back?”

“My mother,” the man admitted, then leaned forward, one strong hand braced on Eva’s table and the other pushing the curtain farther aside. “Did she fall or something?”

“Um,” Eva said, “I think she took off with some man on a motorcycle. I couldn’t see his face because he wore a helmet. They took off down the road, probably toward the interstate.”

“Oh, man, you’ve got to be kidding.” He’d had a stoic, too-serious expression from the time they’d entered the restaurant, but now she could clearly read shock all over his face.

Eva shook her head, not kidding.

He marched over to his table and ordered Timmy, “Stay here. I’ll be right back.”

The boy didn’t move. Hadn’t since he’d spilled his water. But once his father turned away from him, he started edging to the floor and under the table.

As Eva and Jane watched, the man stepped outside, looked to the right and left. Not much happening on this blistering August day. It was after the noon rush, and the parking lot was empty save for four cars, including the one Eva had watched him arrive in.

Then he came back inside. Timmy was completely under the table, thumb in mouth, beginning a curious humming sound. The man walked past him, straight for Eva. “Tell me what you saw,” he ordered.

“I saw her leaving.”

“Story of my life,” he muttered.

Chapter Three

He must have quite a story, but Eva didn’t want to know what happened in the next chapter. She liked her days to run smoothly. She’d spent her whole life, it seemed, trying to make sure the people around her were happy and that everything was in its place.

Sometimes she succeeded.

The past hour left her feeling worried and disgruntled. She exited the restaurant and climbed into the royal-blue Ford F-250 pickup decorated with the logo and phone number for the Lost Dutchman Ranch.

Driving out of Apache Creek township and into the rural area where the ranch waited, Eva remembered every detail from the restaurant. The man had obviously just had a son dropped in his lap by a mother who wasn’t much of a mother—or grandmother, apparently. Eva couldn’t even fathom the type of woman who’d sneak out of a restaurant leaving family behind not knowing.

She wondered how the man would get Timmy out from under the table. She had never been around reticent children. Her sisters had never been afraid to show their feelings.

She didn’t remember fear being part of her childhood—not fear of people, anyway. Fear of horses was a whole different story. The worst thing, the thing that made the Hubrecht clan dysfunctional, was her dad’s habit of thinking he always knew best, and that his word was law, to be followed without question. But he’d never made them feel like they should be afraid. He’d never raised a hand to them. His punishment was “You’re grounded. No television or horse privileges for a week.” And under all the bluster was a heart made of gold. Eva saw it even if her sisters didn’t.

But Timmy was afraid.

Eva could only wonder what would happen to the boy now that the man had been left in possession of his son. And she couldn’t quite shake the connection she’d felt with the man the first time his gaze had caught hers. There was something about him that made her want to get involved. But no, she’d held the enabler card before, and it never played well for her.

And this time, she hadn’t even gotten the name of the man who caused her such angst.

Pulling into the Lost Dutchman Ranch, she finally relaxed. She felt like she’d already put in a full day, though it was just past lunchtime. No way could she be a social worker like her sister Elise. Her small involvement with the people at the restaurant had totally drained her.

“We have nothing to complain about,” she announced to Patti de la Rosa, Jane’s mom, as she entered the lobby and headed for the front desk.

“I told you that a long time ago. Jane just called and told me all about what happened at the restaurant. Poor man. Jane says he’s still there trying to get his son to come out from under the table. I’m going to add him to the prayer list at church.”

Eva sat down behind the front desk and checked the answering machine and their website.

“You don’t want to do that,” Patti advised her. “It’ll just depress you.” As office assistant and head of housekeeping, Patti knew everything there was to know about the workings of the Lost Dutchman. “I already put up the cancellation specials. Not even ten minutes passed before a family called in, canceled their original reservation and hung up. Then, five minutes later, they called and re-reserved under the special price, this time using the husband’s name and card.”

Eva closed her eyes. When a block of rooms suddenly opened up, it was good policy to offer last-minute price breaks to potential guests who might be looking for spur-of-the-moment deals.

Today it hadn’t worked in the ranch’s favor.

“We did get two bookings for October,” Patti said helpfully.

October filled no matter what. Snowbirds flocked to Arizona for its perfect weather.

“I was really hoping for a good summer season,” Eva said. “I need to go find Dad and tell him we can’t afford this new hire. We can’t.” She checked the dining hall, the kitchen and her dad’s office. He wasn’t in their living areas. Standing on the back porch, she looked down the desert landscaping and toward the barn. That’s where he’d be.

She had a love/hate relationship with the barn. On one hand, she hated the way it made her feel: scared, trapped, inadequate. On the other, she came from a long line of horsemen and very much wanted to join their ranks.

She wanted to ride with her dad, her sisters, her someday children.

Go down there, she told herself. You’re a grown woman, strong, and you manage the Lost Dutchman. All of it.

Her feet obeyed, and one step at a time, she walked the half mile to the barn. She could have hopped on one of the ranch’s all terrain vehicles, but that would have gotten her there sooner. She’d face the barn when she got there, but she wasn’t exactly in a rush to make that happen.

She found her father in the saddle room, mending a hobble strap. Chris LeDoux played on the radio.

“You gonna tell me what’s going on, Dad? Do we really need another hand?”

Jacob Hubrecht still had a full head of hair, light brown and brushed to the side. His eyebrows were bushy, his mouth wide. Age had given him wrinkles, very defined, but he still looked strong, and had certainly held on to all his stubbornness through the years. He didn’t pause in his task. “I know what I’m doing. I’ve got the good of the ranch in mind. Leave it be.”

Her two younger sisters had rebelled against his unyielding authority. Eva, however, usually understood where her father was coming from and agreed. Not this time, though.

She didn’t move, just stared at him.

“I’m not getting any younger,” he finally said. “It’s time to put some new, young, strong employees into place—” his hands, always so capable, formed into fists “—so that when I need to work less, I can know all is being cared for.”

He had to be talking about the horses because Eva could do everything else.

She wanted to do everything. Then he wouldn’t be hiring a hand they couldn’t afford.

Behind her, a horse snorted as if reading her mind and knowing she couldn’t possibly care for the mares and geldings like her father did.

“So, this new guy is permanent?”

“Probably not. Mike Hamm called and asked for a favor.”

Mike Hamm was the prison minister. Yes, this was an example of her father not being able to say no to another hard-luck case.

And deep down, she knew he was thinking, “I have three beautiful daughters, but I needed to have me a boy.”

Well, Eva could shoot as well as any boy. Her younger sister Elise could ride like a boy. And the baby of the family, Emily, was a master with a hammer and nails. Half the fences on the ranch were still standing because of Emily. As a matter of fact, Emily had helped Dad draw the plans for most of the Lost Dutchman’s lodgings.

Eva shifted nervously on her feet, all too aware of the two ailing horses in the barn who restlessly watched her. One had stepped on a muck rake and suffered a gash near her eye. Dad was keeping her under observation for a day or two. The other had a dislocated ankle. His future looked grim.

Eva was no help at all. The sight of blood made her woozy, and the thought of trying to help hold a horse while a vet or some of the hands examined it made her...yup, just as woozy.

She’d owned fifty plastic horses as a preteen. She’d had posters of horses on her wall. She’d read Black Beauty and all the Walter Farley books twenty times. Yet the real McCoy, an actual horse, scared her to death.

Daisy, the horse with the gash, snorted again.

Her dad continued. “I know he needs a job. I know he moved a lot and was in foster care. He needs a place to set down roots. Mike says he worked at horse camps during a few summers and remembers the time as the best in his life.”

Great, she was being replaced by a city slicker who only had to muck stalls for two and a half months a few summers.

“I don’t like this change—” Eva had more to say, but Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson’s “Mammas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys” started playing. Her father pulled his cell from his back pocket and answered, “Hubrecht.”

As she walked away, she could hear him saying, “Yeah, I’ve been expecting your call.”

And wasn’t that typical. With a stranger, some shiftless criminal he’d never even met, her father was all expectation. But he had no expectations for her.

Just disappointment.

* * *

Jesse gathered up every crumb left over from lunch and loaded the food into a doggy bag. The monotonous task gave him time to think about what on earth he was going to do now that he had his son in his care.

He’d spent about twenty minutes on the waitress’s cell phone, calling his parole officer and Mike Hamm to update them on his situation. The parole officer gave him an emergency appointment for tomorrow. Mike Hamm’s voice mail promised only that Mike considered the call important and would return it as soon as possible.

Jesse knew no other people’s phone numbers, except for the man offering him a job. Taking the keys from the table, Jesse paid the check—twenty dollars gone. Then he tried to get Timmy out from under the table for the second time.

Timmy was happy under the table.

It took another thirty minutes and a dish of ice cream, but finally he hustled Timmy out the door and toward the old Chevy. At least his mother, or really Matilda, had left something substantial behind. Maybe he could sell it.

Good thing his mother hadn’t thought of that.

A quick search through the backseat showed that the suitcases and dirty laundry were all Timmy’s. The half-full boxes contained old games and toys. Not one item in the car belonged to Susan.

Timothy Leroy Scott’s birth certificate was in an envelope in the glove box. Matilda’s name was in the box labeled Mother, but no name was listed for Father. Jesse did the math. Timmy would be five and yes, he’d been with Matilda during the time she’d conceived Timmy.

He reminded himself to be glad his mother had gotten more organized. When she’d dumped Jesse with relatives, sometimes school wasn’t an option because he never arrived with a birth certificate.

Maybe that’s why he’d never finished high school—too far behind and too busy trying to survive.

“This car belong to your mother?” Jesse asked.

Timmy stared at the ground.

“What am I going to do with you?” Jesse asked.

Timmy didn’t move, not an inch.

“Has Matilda—has your mother—left you before?”

Finally a vague response, a slight shake of the head. At least, Jesse thought it was a shake. It could have been the kid simply needed to get his hair out of his eyes.

“Well, get in.”