Полная версия

The Gynae Geek

Periurethral/Skene’s glands I’ve often been asked at parties by overexcited men about female ejaculation. Well, these are the glands that are responsible for this phenomenon, and they are the female version of the prostate gland. The fluid they make is thought to offer some protection against the bugs that cause UTIs. Infrequently, they can get blocked and swell up, causing a cyst, which can sometimes be confused with a vaginal-wall prolapse.

Vagina This refers to the muscular tube inside that goes from your vaginal opening on the outside, up to the cervix. Your vagina cannot be seen from the outside (hence the inaccuracy of the question: ‘Does my vagina look normal?’), and at about 7–9cm long, it has an amazing degree of elasticity and can expand in all directions – enough to allow for the birth of a baby. Its expansive nature also means it can also accommodate many a foreign object.Possibly the most unusual thing I’ve ever removed from someone’s vagina was a disco ball. Not a massive one from the ceiling of a 70s club, but one that was golf-ball-sized and originally belonged on a key chain. It was 7 a.m., and the end of a particularly harrowing night shift in A&E, but having been told that the offending object was a key ring, I thought it would be a quick job. Then the triage nurse casually added: ‘Oh, by the way, Doc, the key ring itself has snapped off and it’s just the disco ball left inside now …’ Needless to say, it certainly was a challenge, largely due to the fact that your vagina can make a pretty impressive vacuum, but I got it out in the end. If the owner of said disco ball is reading this, I just want to say how much I still feel your pain and embarrassment to this very day.

Labia majora These are the larger, skin-covered outer lips of the vulva. The skin here is usually darker than the rest of the surrounding skin and has a fatty layer underneath that plays a protective role.

Labia minora These are the inner, more fleshy-looking lips, that are usually quite red or pink and probably what cause the most concern with regards to what’s ‘normal’. Most women’s labia minora will be visible below the labia majora and it’s common for them to be asymmetrical. The average size ranges from 2–10cm in length and 1–5cm in width1 and consequently the appearance of the labia minora varies significantly from one woman to the next. It’s kind of ironic how teenage boys (and let’s be honest, most immature men) boast about the size of their penis, yet women are expected to have neat, tucked-in labia that never see the light of day. Why is this? Because they originate from the same embryological structure. It is normal for them to seem to enlarge slightly with age due to loss of collagen and oestrogen, both of which support the structure of the tissue.

Perineum This is the area between the back of the vaginal opening and the anus.

Pelvic-floor muscles Your pelvic floor is underneath the skin of the perineum and is made up of several muscles and pieces of connective tissue that act as a sling to hold your insides in. Pelvic-floor weakness can lead to prolapse of the vaginal walls, bladder, urethra or the uterus. A lot of people think you can only get a prolapse if you’ve had a baby, or if you’ve had a vaginal delivery, during which these muscles may tear or be cut to facilitate delivery. However, this is not the case, and it can happen to anyone – regardless of whether they’ve only ever had C-sections, or even if they’ve never had a baby. The pelvic-floor muscles also help you to maintain control of your bladder and bowel.

THINGS YOU’VE ALWAYS WANTED TO KNOW, BUT WERE TOO AFRAID TO ASK

Is ‘down-there’ hair removal safe?

Generally speaking, yes. Minor cuts, burns and ingrown hairs may occur as a result, but they’re rarely severe enough to require medical attention. The most commonly reported reason given for removing pubic hair is for hygiene purposes,2 however there isn’t actually any evidence to show that it improves hygiene or reduces the risk of infections. I think this belief is perpetuated by the myth that your vulva and vagina are dirty and teeming with germs. As doctors, we don’t judge or have a preference about the terrain down there, so don’t feel you have to schedule a waxing/shaving session before an appointment. I’ll take it as it comes, thank you!

Will having lots of sex make my vagina loose?

No. Regardless of what the teenage boys in the playground may have said, this is not true. Your vagina is very elastic and can expand enough to let a baby out (and other objects in) but it always shrinks back. While having a baby may change the shape of your vagina slightly, having sex will not because a penis is not large enough to do so. Having sex will also not change the size or shape of your labia minora.

Do I need a labiaplasty?

Absolutely not! Labiaplasty is surgery to trim the labia minora and/or clitoral hood. It is largely performed for cosmetic reasons. I think that the sudden interest in ‘neatening up’ one’s labia may be an undesirable offshoot of the current obsession with aesthetic ‘perfection’. There are numerous plastic surgeons around the world advertising labiaplasty as a quick and simple procedure to make your labia more symmetrical/neat and tidy, etc. But symmetry is overrated – no other body part is truly symmetrical: we’ve all got one foot that’s bigger than the other, eyebrows that don’t match. And it’s the same with labia. It’s also normal for your labia minora to be visible on the outside, although Barbie and the porn industry may tell you otherwise. There is minimal evidence to show that the surgery actually improves pain, sexual function or how women feel about their genitalia, plus there is a risk of pain after the surgery due to nerve damage or resulting scar tissue, so it’s really not a decision to take lightly. And it cannot be reversed in the same way that you could, for example, have breast implants removed. As a famous professor once pointed out: ‘If you think your labia are too long, stop shaving off your pubic hair and you’re unlikely to think so.’

When should I start doing pelvic-floor exercises?

Right about … now! Also called Kegel exercises (see here), everyone should be doing them, regardless of whether they are pregnant or have ever had a baby, because that’s not the only thing that weakens them. They generally weaken with age, so you want them to be as strong as possible from a young age. Doing pelvic-floor exercises in pregnancy, especially from an early stage, has also been shown to reduce the amount of time it takes to push your baby out, and the risk of leaking urine after the birth.3, 4 Many people think having a Caesarean section prevents pelvic-floor weakness, but that’s not the case. Carrying around several kilos of extra weight for nine months will put extra strain on the pelvic floor whether you push out that watermelon or it comes out the sunroof!

THE GYNAE GEEK’S KNOWLEDGE BOMBS

The female vulva can generate a great deal of anxiety, but I hope you now feel more comfortable with describing the different areas should you ever need to talk to a doctor about it.

The following are the key facts that I would like you to take away from this chapter:

Your vulva is on the outside; your vagina is on the inside.

Your vulva looks normal. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Pubic hair removal is safe but doesn’t carry any health benefits, so don’t feel you have to do it.

You do not need a labiaplasty if it’s purely for appearance reasons. It’s normal for your labia minora to hang below the labia majora and for one to be longer than the other. It’s Barbie who got that part wrong, not you.

Your pelvic-floor muscles are the lifelong friends that you need to get to know. Kegel exercises (see here) are the most underrated workout that we should all be doing, not just in pregnancy.

CHAPTER 2

Internal female genital anatomy

(While I’m performing a vaginal examination to look at a patient’s cervix):

‘Doctor, do my ovaries look healthy?’

To be clear, I can’t see your ovaries when I’m looking up inside your vagina. Yet I’ve been asked this question on multiple occasions, which tells me that many women may need a refresher of that uninspiring biology class that we all sat through at school. I’ll tell you about the cervix – what even is that? And a cervical ectropion, which is actually very common and completely healthy, yet one of the most anxiety-provoking things that I find myself explaining again and again. I’ll also tell you about a few of the interesting lumps and bumps that I spend a lot of time talking about in clinic that can cause a lot of confusion, usually made worse by my rogue friend Dr Google.

The uterus

The uterus is also known as the womb, and we often use the terms interchangeably. I’ll use the word uterus from now on, you know, in the name of being proper and all.

The uterus is a muscular structure found in your pelvis, behind your bladder and in front of your bowel. It’s roughly pear-shaped, although I often describe it to patients as an upside-down wine bottle, with the large part of the bottle representing the body of the uterus and the neck representing the cervix (or neck of the womb), which acts as a passage for sperm to enter the uterus and menstrual blood or babies to exit. The wall of the uterus is made of smooth muscle, which moves in a ripple-type motion as opposed to striated muscle, which is the type you flex on demand in the gym. You might think that your uterus only contracts during labour, and while this may be the time when it performs its most vigorous workout, it also contracts during your period, helping the menstrual blood to escape, and during female orgasm. Given that these contractions are what cause you to have period pain, it’s not unusual for some women to experience a similar kind of pain for a few hours after sex, either due to orgasm-induced contractions or just because their uterus actually gets a bit irritated from being poked about.

Endometrium

The endometrium is the lining of the uterus, and is at its thinnest around your period, gradually thickening throughout the month to make a nice, soft, juicy landing for a fertilised egg. If this doesn’t happen, the lining is shed when you have your period. The thickness of the lining at the end of the month will determine how heavy your period is, and also, to some extent, how painful it may be – because the more there is to shed, the more the muscle of your uterus may need to contract to help move it out through the cervix and down into the vagina.

The cervix

The cervix or ‘the neck of the wine bottle’ is the gatekeeper to the uterus. Not only does it have a mechanical function of keeping your uterus shut during pregnancy, it also has a pretty complex immune function. A large quantity of the vaginal discharge that you produce comes from the cervix. Discharge is clever and anxiety-provoking in equal measures, which is why I have given it its own chapter (see Chapter 6). But until you get to that section, be aware that it’s way more than just a lubricant and contains loads of ‘natural antibiotics’ that protect you against infections, and that changes in the texture and qualities of the discharge throughout the cycle can determine whether sperm is able to enter.

If you feel your cervix (for non-squeamish readers, this involves inserting your finger into your vagina and feeling right at the top), it usually feels like the tip of your nose, because there is a little indentation in the middle. This is called the ‘external os’ and is the entry into the cervical canal; the small tunnel that runs through the cervix up into the cavity of the uterus. The canal is usually only a couple of millimetres wide, but during labour it opens up to 10cm, which is what we call ‘fully dilated’. Prostaglandins are the chemical messengers that cause contraction of your uterus during your period, and they also cause your cervix to soften slightly, opening a tiny bit to allow blood to escape with ease.

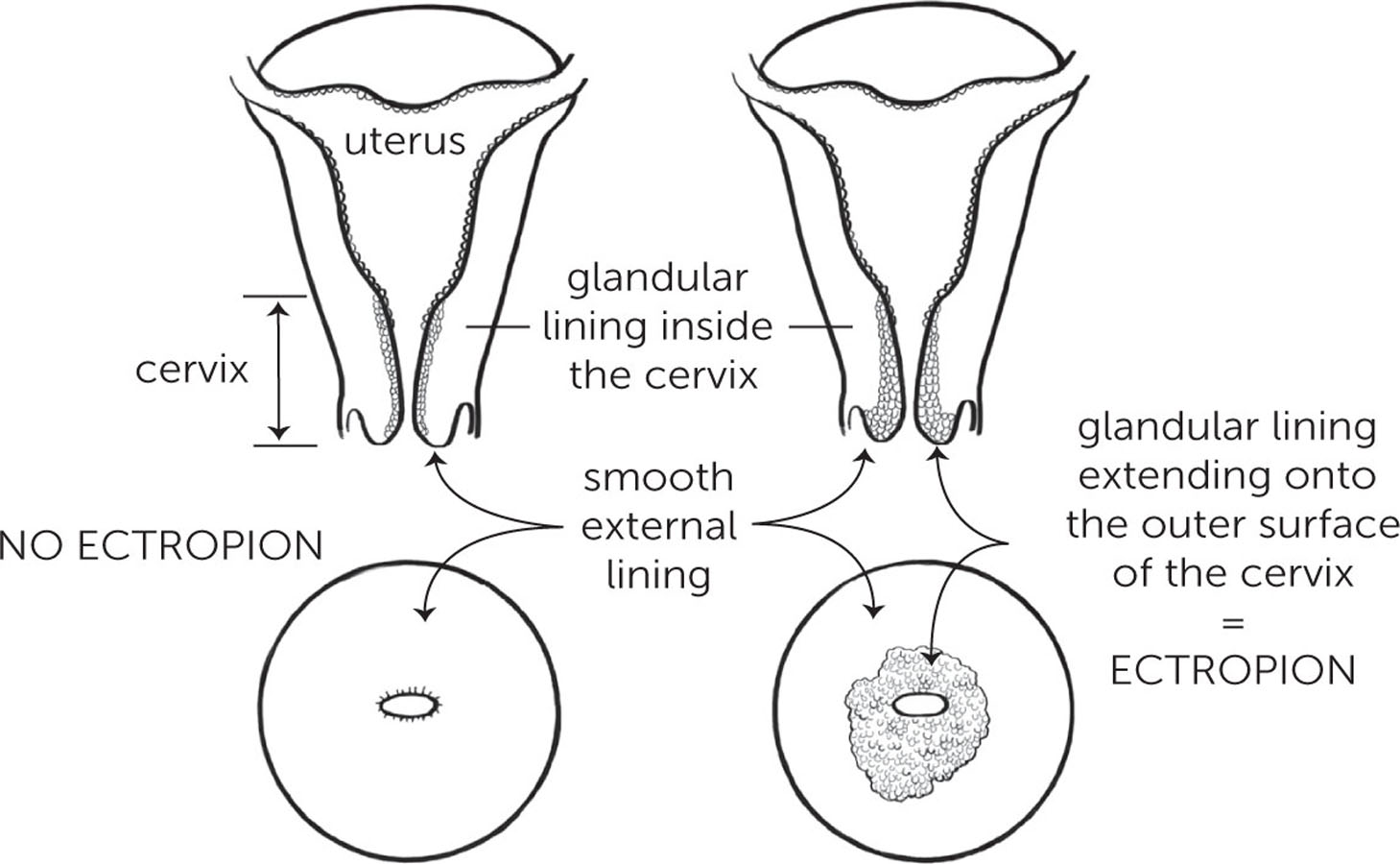

Cervical ectropion

An ectropion is an exposed area of the glandular lining of the inside of the cervix. Not everyone has one, but those who do are often terrified. And understandably so, because it is not something that is usually described clearly. So let me give it a go … Normally, the outer cervix is covered entirely with a smooth lining that’s quite tough and similar to the skin lining the inside of the vagina. But the glandular lining is a bit rough in texture, yet more fragile, and produces most of the protective discharge that I’ll cover in Chapter 6. It’s most common to have an ectropion when taking the combined oral contraceptive Pill, or during pregnancy, but loads of women just have one for no particular reason. They’re not associated with a higher risk of abnormal smears, or with any other disease. They can be bloody annoying though – literally. They tend to bleed on contact, such as during a smear test or during/after sex due to the fragile nature of the glandular lining. It doesn’t mean anything is wrong, it’s just that the lining isn’t really designed to be exposed in such a way.

Having said that, lots of women have an ectropion and never know because they don’t all bleed. If you do have one it can go away on its own; especially if you’re on the Pill it will often disappear when you stop taking it. But if the bleeding is really annoying, there are things that can be done to treat it, such as having the exposed glandular layer burned away, which is what a lot of websites will recommend. Many women come to clinic insisting they want it removed; we generally advise against it unless it’s really problematic, and the vast majority change their mind once I’ve explained that it’s not harmful. As one patient once said to me, ‘If it’s nothing sinister, I’ll take a few harmless drops of blood over a barbecue on my cervix any day.’

Cervical polyps

These are little ‘skin tags’ that can be found in the cervix. Many women have them and never know, but in some they cause symptoms of abnormal discharge (a change in colour, texture, amount or bloodstained), bleeding in between periods, after sex or after a gynaecological examination, which makes them super annoying, and a potential source of worry. They may also be found by chance during a routine examination such as a smear test. They can be removed easily in clinic, and it’s quick and painless, but if they’re not causing symptoms this is unnecessary, as they are always benign (non-cancerous) and don’t increase the risk of any kind of disease or trouble in the future.5

Nabothian follicle

Also called mucus-retention cyst, this is where the mucus that is made as part of the healthy function of the cervix becomes trapped underneath the surface of the cervix. Most often, these cysts are just an incidental finding when you’re having a speculum examination, and they’re usually too small to be felt, although if you touch your cervix, you may be able to feel the little lumps. They are completely normal and don’t increase the risk of any kind of gynaecological disease, nor are they anything to do with sexually transmitted infections. A patient once told me that another doctor described them as spots/whiteheads on her cervix, and she had thought it was because she wasn’t washing her vagina enough; so she went to town with various feminine-hygiene products, which didn’t make them go away and just gave her terrible vaginal irritation. If you have them, you can’t do anything to make them go away and you don’t need to either.

Fallopian tubes

You have two fallopian tubes – one on the left and one on the right, coming off the top of your uterus like long ears that flap around and pick up eggs from the ovaries. I recently scanned a lady who was ecstatic to find out she was seven weeks pregnant. I showed her the pregnancy in the uterus with a heartbeat and told her I could see the egg had come from the left ovary. She looked baffled and said it wasn’t possible because she’d had her left tube removed three years before due to an ectopic pregnancy (where the fertilised egg implants itself outside the uterus, usually in one of the tubes). However, your tubes are incredibly mobile – like a motorbike courier, they’ll pick up from any location if the goods are ready and waiting. So even with one tube, eggs can still be picked up from either ovary. The tubes contain tiny little finger-like projections called cilia, which help to sweep the eggs along into the uterus. However, they are not directly attached to the ovaries, and open into the pelvic cavity, which can serve as a route for infections to spread from your vagina, which is how sexually transmitted infections in particular can spread and cause pelvic inflammatory disease (see Chapter 9).

Ovaries

You have two ovaries, which are held close to your uterus by two ligaments – one that attaches to the wall of the inside of your pelvis and one that attaches to your uterus. The ovaries are home to a woman’s egg supply, which is complete at birth (about 2–4 million). The number of eggs decreases gradually as we age, with about three to five thousand ultimately making it to the point of being released. This is called ovulation and usually happens about once a month. The eggs live in little sacs called follicles, which go through several days of maturation to eventually form a cyst: a fluid-filled sac which bursts and releases an egg which may or may not then be fertilised.

Your ovaries are also a major site of hormone production, making the following:

Oestrogens Oestrogens, of which there are three types (oestrone, oestrodiol and oestriol), are not only responsible for your menstrual cycle, but also play a role in memory, heart health, bone strength and even the immune system.

Progesterone The major site of progesterone production is from the corpus luteum – this is the ‘shell’ that is left behind in the ovary after ovulation. If you don’t ovulate, very little progesterone will come from the ovaries themselves and the adrenal glands. (These glands sit above your kidneys and are responsible for making small amounts of progesterone along with a whole host of other very important hormones.) Levels are highest seven days after ovulating – that is Day 21 if you have a twenty-eight-day cycle – so if you’re having blood tests to see if you’re ovulating, this is what will be checked. If your level is low, you either didn’t ovulate or the timing of the test was wrong. The latter is surprisingly common, and a lot of scared patients come to clinic worried that they’re not ovulating. On further questioning, they do describe all the signs of ovulation (see Chapter 3), and I’m then able to help them work out when to do the test, after which they come back very happy with a nice high progesterone reading.

Inhibin This hormone sends a message from the ovaries back to the brain saying, ‘We’re being stimulated enough, thanks’.

Relaxin This is a hormone which causes the joints and ligaments to soften during pregnancy to prepare the body for labour. It’s also responsible for the joint pain that pregnant women often experience.

Testosterone This is usually associated with men, but believe it or not, women need it too – not just to promote sex drive, but also for bone and muscle strength, as well as brain function.

THINGS YOU’VE ALWAYS WANTED TO KNOW, BUT WERE TOO AFRAID TO ASK

What is a retroverted uterus and will it affect my chances of getting pregnant?

Also known as a tipped/tilted uterus, it means the uterus points backwards (retroverted) instead of forwards (anteverted). Between 20 and 30 per cent of women have this and in many cases, it is just how they were born and bears no impact on their health. In some women, however, it may be due to conditions such as endometriosis (see here), fibroids (see here) or the presence of scar tissue that pulls the uterus backwards. The actual position of the uterus does not affect your chances of getting pregnant because sperm is able to swim in all directions; however, any one of the underlying conditions above may cause problems. It also doesn’t cause pain, but again, if it’s due to an underlying disease, that may do so.

A retroverted uterus can make your cervix a little trickier to find when you have a smear test, which can be slightly uncomfortable. But we know plenty of tricks to make it easier and less painful. I often use the ‘make-fists-and-put-them-underneath-your-bottom’ position – if you know, you know! But the smear itself shouldn’t be any worse than normal.

As the uterus increases in size in pregnancy, it will gradually flip forward, and by twelve weeks – when most women are having their first scan – a retroverted uterus may have corrected itself, so that many women never even find out they had one.

Why do I bleed after sex?

Also called post-coital bleeding, bleeding after sex can have many causes, including:

cervical ectropion (see here)

cervical and endometrial polyps (see here)

infections such as chlamydia, or even something simple like thrush, which causes irritation of the vagina and cervix and the added friction of sex can be enough to make it bleed

vaginal dryness (lack of lubrication, which can make the vaginal tissue more sensitive to friction in particular)

skin conditions such as psoriasis or lichen schlerosus – these can make the skin more delicate and increase the chance of getting small skin tears

cervical cancer – the one that everyone worries about, but is actually the least likely cause, which is why I’ve put it at the bottom of the list; the risk ranges from 1 in 44,000 cases of post-coital bleeding in women aged 20–24 to 1 in 2,400 in 45–54-year-olds.6

Does removing a fallopian tube affect my fertility?

Sometimes fallopian tubes may need to be removed in cases of severe infections (see Chapter 9 on STIs) or due to an ectopic pregnancy (a pregnancy in the tube). You can still get pregnant with one tube (see here), but if both are removed it does mean that you would need IVF to get pregnant. Removing either one or both tubes also does not affect the function of your ovaries and does not cause you to go into the menopause.

Why do I have a cyst on my ovary?

Ovarian cysts are very common and about 1 in 10 women will need surgery for one at some point in their lifetime. Most arise as a result of the normal workings of the ovary (see here). We get tonnes of referrals to the gynaecology clinic for ovarian cysts that have been found incidentally during a scan for something else. Ultrasound is the best way to look at your ovaries initially, preferably an internal scan using a small probe inside the vagina because it gets closer to the action. Most cysts will disappear on their own within a couple of months. You may need a follow-up ultrasound, depending on the size and type of cyst.

Larger cysts may need to be removed because there is a greater risk that they may twist the ovary which cuts off its blood supply, and if not untwisted will cause the ovary to die. This is called ‘ovarian torsion’, and you’ll definitely know if you have it because it is incredibly painful, to the point where even morphine won’t touch the pain. It requires emergency surgery to untwist the ovary and remove the cyst. In most cases the ovary itself can be saved if the blood supply returns on untwisting.

The biggest ovarian cyst I’ve ever seen was in a young woman and was 24cm across. She was supermodel-slim, and finally went to her GP after spending a fortune on pregnancy tests, because she couldn’t understand why they were all negative, yet she looked seven months pregnant. A big tummy is a slightly unusual way for a cyst to present. More common symptoms include: