Полная версия

The Red Wyvern

KATHARINE KERR

THE RED WYVERN

Book One of The Dragon Mage

COPYRIGHT

Voyager

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Voyager 1997

Copyright © Katharine Kerr 1997

Cover design and illustration by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Katharine Kerr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

This novel is a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780006478607

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2014 ISBN: 9780007378319

Version: 2019-12-10

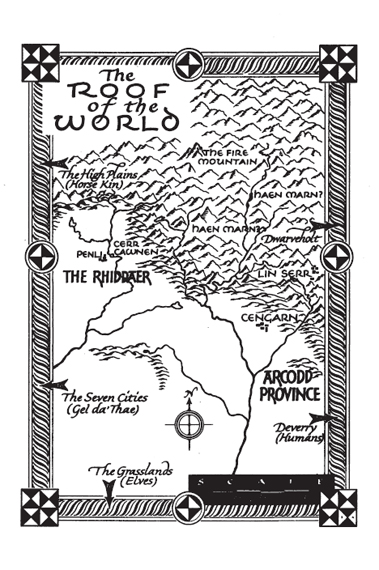

MAP

DEDICATION

For Jo Clayton

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I must apologize to the faithful readers of this on-going project who have had to wait so long for the volume now in hand. I have been much distracted of late by legal matters, in particular the suits and counter-suits concerning a certain Elvish scholar of Elvish and his libellous attacks upon me. When Gwerbert Aberwyn ruled in our favour in Malover, my publishers and I hoped that the matter had ended at last, but alas, our opponent saw fit to appeal to the High King himself. After an ennervating journey by coach and barge on the part of myself and a representative of my publisher, we settled into a suite at a public guesthouse in Dun Deverry and filed our counter-suit. While we waited for our proceedings to be summoned, I once again applied myself to the craft for which I am better suited than legal wrangling, that of writing novels.

Some months later, we are still waiting. Let us hope that the High King’s courts take up and dispose of this matter soon.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Map

Dedication

Author’s Note

Prologue: Winter, in a Far Distant Land

Part One: The North Country

Part Two: Deverry, 849

Part III: The North Country

Epilogue: Spring, in a Far Distant Land

Keep Reading

Appendices

Glossary

About the Author

Other Books By

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Winter, in a Far Distant Land

Some say that all the worlds of the many-splendoured universe lie nested one within the other like the layers of an onion. I say to you that they lie all braided and wound round and that no man nor woman either can map all the roads of their twisting.

The Secret Book of Cadwallon the Druid

Domnall Breich knew the hills around Loch Ness well enough to know himself lost. The hunting accident that had killed his horse and separated him from his companions had happened some two miles straight south, or at least, in that direction and at that distance as closely as he could reckon. By now he should have reached the frozen dirt road that led back to the village and safely. He stopped, peering through the rising mists at the snow-streaked valley, stippled here and there with pines. The gathering dark of the winter’s shortest day shrouded Ben Bulben, the one landmark that might guide him through the mists. When he glanced at the sky, he realized that it was going to snow.

‘Mother Mary, forgive my sins. Tonight I’ll be seeing your son in his glory.’

They always said that freezing was as pleasant a death as any, more like falling asleep to wake to fire and sleet and then the candlelight that would guide you to the gates of Heaven or Hell. Domnall felt no fear, only surprise, that a man like him would die not in battle or bloodfeud but in the snow, lost like a lame sheep, but then the priests always said a man could never tell the end God had in store for him.

Ahead against the grey of clouds, the western sky gleamed dull red at the horizon. When he faced the glow and looked round, he saw off to his right, at the edge of his vision, a tall tree. He turned and sighted upon it. His last hope lay in keeping a straight course toward the north, the general direction of the loch, which ran southwest to northeast. If he reached the edge of that dark gash in the land, he could follow it and head for Old Malcolm’s steading, which he just might, if Jesu favoured him, live to reach. Worth a try, and if he were doomed, he might as well die on his feet. He wrapped his plaid tight around him, pulled his cloak closed around it, and walked north.

The first thing he noticed about the tree was that it grew straight and remarkably tall. As the sunset faded into darkness, he noticed the second thing, that it was burning. Here was a bit of luck! If he could nourish a fire against the snow, it would keep him through the night. As he drew close, he noticed the third thing, that although half of the tree blazed with fire, the other half grew green with new leaf. For a moment he could neither speak nor breathe while all the blood in his veins seemed to freeze like water spilled into snow. Was he already dead then?

‘Jesu and the saints preserve,’ he whispered. ‘May God guide my soul.’

‘It’s a waste of your breath to call upon the man from Galilee,’ the voice said. ‘He doesn’t do us any favours, and so we do none for him.’

Domnall spun around to find a young man standing nearby. In the light of the blazing tree he could see that the fellow was blond and pale, with lips as red as sour cherries and eyes the colour of the sea in summer. He’d wrapped himself in a huge cloak of solid blue wool with a hood.

‘And are you one of the Seelie Host, then?’ Domnall said.

‘The men of your country would call me so. There’s a great grammarie been woven at this spot, and it’s not one of my doing, which vexes me. What are you doing here?’

‘I got lost. I wish you no harm, nor would I rob you and yours.’

‘Well-spoken, and for that you may live. Which you won’t do if you stay out in this weather much longer. I need a messenger for a plan I’m weaving, and it’s a long one with many strands. Tell me, do you want to live, or do you want to die in the snow?’

‘To live, of course, if God be willing.’

‘Splendid! Then tell me your name and the one thing you wish most in all the world.’

Domnall considered. The Seelie Host were a tricky bunch, and some priests said them no better than devils. Certainly you were never supposed to tell them your name. Something touched his face, something cold and wet. In the light from the blazing tree he could see snow falling in a scatter of first flakes.

‘My name is Domnall Breich. I most desire an honourable death in battle, serving my liege lord.’

The spirit rolled his eyes.

‘Oh come now, surely you can think of a better boon than that! Something that would please you and bring you joy.’

‘Well, then, I love with all my heart the Lady Jehan, but I’m far beneath her notice.’

‘That’s a better wishing.’ The fellow smiled in a lazy sort of way. ‘Very well, Domnall Breich. You shall have the Lady Jehan for your own true wife. In return, I ask only this, that you tell no one of what you see here tonight except for your son, when he’s reached thirteen winters of age.’ The fellow suddenly frowned and drew his hands out from the folds of his cloak. For a moment he made a show of counting on his fingers. ‘Well, thirteen will do. Numbers and time mean naught to the likes of me. Whenever you think him grown to a man, anyway, tell him what you will see here tonight, but tell no one else.’

‘Good sir, I can promise you that with all my heart. No one but his own son would believe a man who told of things like this.’

‘Done, then!’ The fellow raised his hands and clapped them three times together. ‘Turn your back on the tree, Domnall Breich, and tell me what you see.’

Domnall turned and peered through the thin fall of snow. Not far away stood a tangle of ordinary trees, dark against the greater dark of night, and beyond them a stretch of water, wrinkled and forbidding in the gleam of magical fire.

‘The shore of the loch. Has it been here all this while, and I never saw it?’

‘It hasn’t. It’s the shore of a loch, sure enough, but’s not the one you were hoping to find. Do you see the rocks piled up, and one bigger than all the rest?’

‘I do.’

‘On top of the largest rock you’ll find chained a silver horn. Take it and blow, and you’ll have shelter against the night.’

‘My thanks. And since I can’t ask God to bless you, I’ll wish you luck instead.’

‘My thanks to you, then. Oh, wait. Face me again.’

When he did so, the fellow reached out a ringed hand and laid one finger on Domnall’s lips.

‘Till sunset tomorrow you’ll speak and be understood and hear and understand among the folk of the isle, but after that, their way of speaking will mean naught to you. Now you’d best hurry. The snow’s coming down.’

The fellow disappeared as suddenly as a blown candle flame. With a brief prayer to all the saints at once, Domnall hurried over to the edge of the loch – not Ness, sure enough, but a narrow finger of water that came right up to his feet rather than lying below at the foot of a steep climb down. By the light of the magical tree he found the scatter of boulders. The silver horn lay waiting, chained with silver as well. When he picked it up and blew, the sound seemed very small and thin to bring safety through the rising storm, but after a few minutes he heard someone shouting.

‘Hola, hola! Where are you?’

‘Here on the shore!’ Domnall called back. ‘Follow the light of the fire.’

Out of the tendrilled snow shone a bobbing gleam, which proved to be a lantern held aloft in someone’s hand. The magical fire behind cast just enough light for Domnall to see a long narrow boat, with its wooden prow carved like the head of a dragon, coming toward him. One man held the lantern while six others rowed, chanting to keep time. As the boat drew near, the oars swung up and began backing water, holding her steady as her side hove to.

‘It’s a cold night to ask you to wade out to us,’ the lantern bearer called, ‘but we’re afraid to run her ashore with the rocks and all in the dark.’

‘Better I freeze seeking safety than freeze standing here like a dolt. I’m on my way.’

He hitched his plaid up around his waist and bundled the cloak around it, then stepped into the lake. The cold water stole his breath and drove claws into his legs, but it stood shallow enough for him to reach the dragon boat, where hands of flesh and blood reached down to pull him aboard.

‘Swing around, lads! Let’s get him to a fireside.’

Shivering and huddling in the dry part of his plaid, Domnall crouched in the stern of the boat as they headed out from shore. In the yellow pool of lantern light he could see the man who held it, a fellow on the short side but stocky. He wore a hooded cloak, pinned with a silver brooch in the shape of a dragon. In the uncertain light Domnall could just make out his lined face and grizzled beard.

‘Where are we going, if I may ask?’ Domnall said.

‘The isle of Haen Marn.’

‘Ah.’ Domnall had never heard of the place in his life, and he’d spent all twenty years of it in this corner of Alban. ‘My thanks.’

No one spoke to him again until they reached the dark island, looming suddenly out of falling snow, a muffled but precipitous shape against the night. A wooden jetty appeared as well, snow-shrouded in the lantern light, and with a chant and yell from the oarsmen, the boat turned to. One man rose, grabbed a hawser, and tossed it over one of the bollards on the jetty to pull them in. With some help Domnall managed to scramble out, but his feet and legs had gone numb and clumsy. The man with the lantern hurried him along a gravelled path and up a slope, where he could see a broad, squarish manse. Around the cracks of door and shutter gleamed firelight.

‘We’ll get you warm soon enough,’ the lantern-bearer said, then banged upon the door. ‘Open up! We’ve got a guest, and all by Evandar’s doing.’

‘Evandar? Is that the man of the Seelie Host? You know him?’

‘Better than I wish to, I’ll tell you, far far better than that. Now come in, lad, and let’s get you warm.’

The door was creaking open to flood them with firelight and the smell of resinous smoke. They brushed past the servant woman who’d opened it and hurried into a great hall where fires crackled in two hearths of slabbed stone, one on either side of the square room. The walls were made of massive oak planks, scrubbed down and polished smooth, then carved in one vast pattern of engraved lines rubbed with red earth. Looping vines, spirals, animals, interlace – they all tangled together in great swags across each wall, then swooped up at each corner to the rafters before plunging down again in a riot of carving …

Domnall followed his rescuers across the carpet of braided straw to the hearth at the far side. At a scatter of tables sat a scatter of men, all short and bearded, and in a carved chair right up near the fire a lady, wearing a pair of drab loose dresses and heavy with child. Like the men around her, she was not very tall, more like the grain-fed Sassenach far to the south in stature, and since her pale hair hung in a single braid, Sassenach is what he assumed her to be. Domnall knelt at her feet.

‘My lady,’ he said. ‘My thanks and my blessing to you, for the saving of my life.’

‘My men saved you, not me,’ she said in a low, musical voice. ‘But you’re welcome in my hall.’ She glanced round. ‘Otho! Fetch him a tankard and some bread, will you?’

‘As my lady Angmar commands.’ One of the men, a bare four feet tall, and white of hair and beard, rose from a table. ‘Sit in the straw by the hearth, lad, and spread that bit of cloth you’re draped in out to dry.’

They had to be Sassenach, all of them, because they wore trousers and heavy shirts instead of proper plaids and tunics, but he wasn’t about to hold their birth against them after the way they’d rescued him. Since the hearth was a good ten feet long, Domnall could move a decorous distance away from the lady to sit near a brace of black and tan hounds. He unwound his plaid, stretched it out on the straw to dry, and sat in his tunic by the fire to struggle with the wet bindings of his boots. By the time he had them off, Otho had returned with the promised tankard and a basket of bread.

‘A thousand thanks,’ Domnall said. ‘So, this is Haen Marn, is it? I’ve never seen your isle before.’

‘Hah!’ Otho snorted profoundly. ‘And I wish I never had either.’

‘Uncle!’ A young man sprang up from his seat at a table. ‘Hold your tongue!’

‘Shan’t! I rue the day that ever we travelled to this cursed place. I just get myself home and what happens? Hah! Wretched dweomer and –’

‘Uncle!’ The young man hurried over. ‘Hush!’

‘You hold your tongue, young Mic, and show some respect for your elders.’

The two glared at each other, hands set on hips. During all of this Lady Angmar never moved or spoke, merely stared into the fire. Behind her, shoved against the wall, stood another carved chair, fit for a lord but empty. Domnall wondered if she’d been widowed; it seemed a good guess if a sad one.

‘Well, now,’ Domnall said. ‘Do you all hail from the southern lands?’

‘Who knows?’ Otho snapped. ‘It could have been any wretched direction at all!’

‘You’ll forgive my uncle, good sir,’ Mic said. ‘He’s getting old and a bit daft.’ He grabbed Otho’s arm. ‘Come and sit down.’

Muttering under his breath, Otho allowed himself to be dragged away. Domnall had the uneasy feeling that the old man wasn’t daft in the least but speaking of grammarie. Yet his mind refused to take that idea in. He found it easier to believe in a lady sent away by her brothers after a husband’s death, or perhaps even a lady in political exile, allowed to take a small retinue away with her. The Sassenach chiefs were always fighting among themselves, and he’d heard that their women could do what they wished with their bride-price if their husbands died. The welcome fire, the warm straw, the steamy reek of his drying cloak and plaid, the taste of ale and bread – it all seemed too solid, too normal to allow the presence of magic. As he found himself yawning, he wondered if he’d merely imagined the man named Evandar and the blazing tree. They might merely have been the mad visions of a man come near death by cold.

At length Lady Angmar turned and considered him with eyes so sad they were painful to look upon.

‘I can have the servants give you a chamber,’ she said, ‘or would you prefer to sleep here by the banked fire?’

‘The fireside will do me well, my lady, and I’d not cause you any more trouble.’

Her mouth twitched in a ghost of a smile.

‘There’s been trouble enough, truly,’ she said, then returned to watching the fire.

Angmar never spoke again. At length she rose and with her elderly maidservant left the hall. Young Mic brought Domnall a blanket; Otho banked up the fire; they took the lantern and left him with the dogs to curl up and sleep.

When he woke cold grey light edged the shutters. Otho was just letting the whining dogs out at the door. Stretching and yawning, Domnall sat up as the old man came stumping over, poker and tongs in hand, to mend up the fire.

‘I’ll get out of your way, good sir,’ Domnall said.

‘You’re a well-spoken lad.’

‘It becomes a Christian man to watch his speaking.’

Otho glanced puzzled at him.

‘A what kind of man?’ he said.

‘A Christian man, one of Lord Jesu’s followers.’

‘Ah. Is this Yaysoo the overlord in these parts?’

‘Er, well, you could say that.’

Otho hunkered down and began lifting the chunks of sod away from the coals. Domnall pulled on his boots, bound them tightly, then stood up to wrap and arrange his plaid.

‘The Lady Angmar? Has she lost her husband then?’

‘Lost him good and proper,’ Otho said. ‘No one knows where he may be or if he lives or lies dead, and here she is, heavy with his child.’

‘That’s a terrible sad thing.’

‘It is, truly. If she knew he was dead, she could mourn him and get on with life, but as it is …’

‘The poor lady, indeed.’

‘It’s just like him, though, to do something so thoughtless. An inconvenient man, he was, all the way round. Ah, but who knows why women choose the men they do? She’s still wrapped in sorrow over her Rhodry Maelwaedd, no matter what we may say.’

That was doubly odd. What was a Sassenach woman doing married to some lord from Cymru? Or could this be the reason for her exile? Otho glared at the coals, then blew a bit of life into one of them and threw on a handful of tinder.

‘Do you have a home near here, lad?’

‘I do. I serve Lord Douglas and live in his hall.’

‘Then let me give you some advice. Get out of here while you can and head home, or you may never see it again. The snow’s stopped falling, and the boatmen will row you across.’

‘I’ll need to give the lady my thanks first.’

‘She’ll not come down till well past mid-day. Her grief rules her. Get out while you can, while the sunlight lasts, and that won’t be long, this time of year. I warn you.’ The old man glared up at him, his face red and sweaty as the fire leapt back to life. ‘Haen Marn travels where it wills, and faster than spit freezes on a day like this.’

Grammarie. His memories of the night before, of Evandar and the burning tree, came back like a slap in the face. Domnall grabbed his cloak from the straw.

‘Then I’ll be off. Good day to you, Otho.’

The old man snorted and turned back to his work.

Outside Domnall found a day ice cold but clear, with the watery sun just rising – he’d slept late. At the door he paused, looking around him in the crisp day. Wind whined around walls and soughed in trees. He walked a few paces down the path, then turned back for a proper look at the place. In the sun the island seemed much larger than he’d thought the night past. The manse itself stood long and low, with behind it a rise of leafless trees, pale grey and shivering, and behind them a tall, squarish tower, perched on top of a little hill. He shaded his eyes and studied the tower for a moment; it sported three windows, one above the other, and a peaked roof covered in grey slates.

In the middle window someone was standing and looking down. From his distance he couldn’t tell whether it was a man or a woman, but he suddenly knew that he was being watched, studied as intensely as he’d been studying the tower. There was no malice in the gaze, merely a shocking closeness, as if that person in the window had dropped down to stand in front of him. With a shudder he turned away. He could feel the gaze follow him until he started walking toward the lake. When he risked a quick glance back he found the tower window empty.

At the end of the gravelled path he saw the jetty and the dragon boat, riding high in the water. No one seemed to be about, but by the time he reached the jetty, the head boatman and his oarsmen came strolling down the shore to join him. Otho must have sent a servant down to rouse them, Domnall supposed.

‘Ready to go back, lad?’ the boatman said.

‘I am, though I wish I’d had a chance to pay my thanks to Lady Angmar.’

‘Ah, she won’t be down for a good while yet.’ The boatman shook his head. ‘It’s a sad thing.’

They all boarded, and when the oarsmen settled at their thwarts, Domnall sat in the stern, out of their way. Here in daylight he noticed a bronze gong, hanging in a wooden frame. The boatman saw him looking at it.

‘That’s for the beasts in the lake,’ he announced. ‘In this cold weather they sink to the bottom and sleep, or some such thing. Like bears do, you know, in caves. In the summer, they’re a fair nuisance, but luckily they hate noise, and banging that gong keeps them off.’

‘Beasts?’ Domnall said.

‘In the lake, truly. Huge they are, with long thin necks and mouths full of teeth. They can capsize a boat like this as easy as I can squash a bedbug.’

All the oarsmen nodded in solemn agreement.

‘Ah,’ Domnall said. ‘This lake must feed into Ness, then. That gives me hope.’