Полная версия

Trojan Horse of Western History

Harvard philologists Milman Parry and Albert Lord, who in late 1920s and early 1930s studied style of Homer’s epic, also fanned the flames in a way. To learn about the technique for creating, learning and transferring of oral legends they undertook several expeditions to the Balkans to study the living epic tradition. Having collected and studied a huge amount of folklore material, they found out that in time epic was based not on telling some finished texts, but rather on transferring a set of resources used to develop a song: plots, canonical images, and stereotyped word-and-rhythm formulas, which singers used like language words. In particular, this allowed performers to reproduce (or, more precisely, to create in the course of the performance) poems consisting of thousands of lines.[43] Each time the song was an improvisation, though, it remained a form of collective creativity.

Fig. 22. American historian Moses Finley calling on the “deletion” of Homer’s Trojan War from the history of the Greek Bronze Age. (Image © Olga Aranova.)

The folklore nature of Homer’s poems that were of exactly such formula style was proven, thus (over 90 percent of the Iliad text was comprised of such formulas – a staggering number, especially upon considering the refinement and intricacy of the Greek hexameter).[44] It is hard to expect that folklore tales would mirror some true historical reality.

Moses Finley, a reputable historian, insisted on that point, too. In his book The World of Odysseus (1954), he affirmed that searching through Homer’s works for authentic testimonies concerning the Trojan War, its causes, outcome and even composition of coalitions is just the same as studying the history of Huns in the 5[[th]] century by the Song of Nibelungs or appealing to the Song about Rolland to reconstruct the course of the Battle of Roncevaux Pass. Finley grounded his doubts on both the data for comparative philology and results of the economic history study of Homer’s society by means of the model proposed by French anthropologist Marcel Mauss.

In his famous book The Gift (1925), Marcel Mauss studied the mechanism of operation of traditional society’s economy based on the gratuitous expenditure principle. According to Mauss, archaic economy does not push advantages. At its bottom there is the potlatch (a holiday held to distribute all of the tribe’s property; however, another tribe receiving the gifts undertakes to make a greater and more generous potlatch. Thus, accumulated and spent wealth circulation starts, for the prestige of ones and enjoyment of others.[45]

By reconstructing the system of exchange in the Hellenic world, Finley discovered that the socio-economical relations mirrored in Homer’s poems were close to those existing under eastern despotism and that they were absolutely untypical for the Mycenae society during the Trojan War period (13[[th]] and 12th centuries B.C.). The Iliad and the Odyssey somewhat restored the reality of the 10[[th]] and 9[[th]] centuries B.C. (i.e. the Dark Ages). On this basis, Finley directly stated that the Trojan War depicted by Homer should be razed from the history of the Greek Bronze Age.

Moses Finley had written his book before Michael Ventris and John Chadwick published deciphered results of the so-called linear writing B – the most ancient syllabary, samples of which were found on artifacts of Mycenae Greece.[46] The article Evidence for Greek Dialect in the Mycenaean Archives[47] by Ventris and Chadwick provoked a chain reaction in the scientific world. One by one, the studies appeared, reconstructing the Crete and Mycenaean period of ancient history. According to Chadwick’s testimony, 432 articles, brochures and books by 152 writers from 23 countries appeared[48] in the period 1953–1958 alone. These studies demonstrated that linear writing was used in all big centers of Mycenaean Greece as the official writing, and therefore, it was a factor that combined politically different societies in a uniform cultural space. A more important thing was that according to these studied high-level culture and developed political life were there on the Aegean islands of the 2nd millennium B.C.

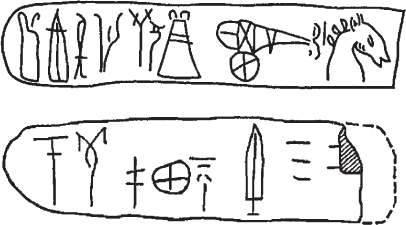

Fig. 23. Knossos plates with linear writing B (XV century B.C.)

Authoritative French historian Paul Fort asserted: “The texts discovered in Knossos, Pylos, Mycenae, Phebe, etc., made it possible, at last, to reconstruct the everyday life of the contemporaries of the Trojan War and even that of a few generations of their predecessors since the 13th century B.C. Due to these, peasants, seamen, handicraftsmen, soldiers, officials once again began speaking and acting. And the golden masks of the Athenian museum became more than simple masks of the dead”.[49]

The results of decryption of ancient written sources, together with analysis of archaeological finds, served as an additional argument in favour of Finley’s and his predecessor’s hypothesis that the author of the Iliad did not realize customs and everyday life of the Hellenes in the 13[[th]] and 12[[th]] centuries B.C.

The results of decryption of the Mycenaean written language, along with analysis of the archaeological finds, confirmed that the author of Iliad did not realize customs and everyday life of the Hellenes in the 13th and 12th centuries B.C.

For the Greek theocratic monarchy in the Trojan War times, the kings were considered as living gods, unapproachable by mere mortals and managing their empires by means of a developed bureaucratic apparatus. According to Homer, the kings were quite close to the people and not devoid of democratic methods of rule.[50]

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

Paul Feyerabend, Against Method: Outline of an Anarchist Theory of Knowledge (London, 1975).

2

Herodotus, Histories, VII, 43.

3

Strabo, Geography, XIII, 26.

4

Lucan, Pharsalia, IX, 964–969.

5

Ecumene (also spelled oecumene or oikoumene) is a term originally used in the Greco-Roman world to refer to the inhabited universe (or at least the known part of it). The term derives from the Greek οἰκουμένη (oikouménē, the feminine present middle participle of the verb οἰκέω, oikéō, “to inhabit”), short for οἰκουμένη γῆ “inhabited world”. In modern connotations it refers either to the projection of a united Christian Church or to world civilizations.

6

Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca, Epitome, III, 5.

7

Osip Mandelstam, Stone (N.Y.: Princeton University Press, 1981).

8

A.I. Zaitsev, “Ancient Greek Epos and the Iliad by Homer”, Homer. The Iliad (St. Petersburg: Nauka, 2008); p. 398.

9

Alessandro Baricco, Omero, Iliade (Collana Economica Feltrinelli, Feltrinelli, 2004).

10

L.S. Klein, Bodiless Heroes: Origin of the Images of the Iliad (St. Petersburg: Khudozhestvennaya Literature, 1992); p. 4.

11

Heinrich Alexander Stoll, Der Traum von Troja (Leipzig, 1956).

12

Under the Russian law Heinrich Schliemann and Yekaterina Lyzhina remained married.

13

V.P. Tolstikov, “Heinrich Schliemann and Trojan Archaeology”, The Treasures of Troy. The Finds of Heinricha Schliemann. Exhibiton catalogue (Мoscow: Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts: Leonarde Arte, 1996); p. 18.

14

А.V. Strelkov, “The Legend of Doctor Schliemann” in G. Schliemann, Ilion. The city and country of the Trojans. Vol. 1 (Мoscow: Central Polygraph, 2009); p. 11.

15

D.A. Traill, Excavating Schliemann: Collected Papers on Schliemann (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1993), p. 40.

16

Seventeen year old Sophia Schliemann was practically bought for 150,000 francs from her uncle, a Greek bishop Teokletos Vimpos.

17

V.P. Tolstikov, “Heinrich Schliemann and Trojan Archaeology”, The Treasures of Troy. The Finds of Heinricha Schliemann. Exhibiton catalogue (Мoscow: Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts: Leonarde Arte, 1996); p. 18.

18

Carl Blegen, Troy and the Trojans (Praeger, 1963).

19

Heinrich Schliemann, Ilios, City and Country of the Trojans (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

20

Actually it was with the publication in 1950 of his epistolary heritage that the perception of Schliemann’s personality began to change. Comparing data from Schliemann’s letters and his autobiography, the researchers found that “the great archaeologist” was lying at every turn.

21

American researcher David Treyll insisted that Priam Treasure was a fraud. D.A. Traill, Excavating Schliemann: Collected Papers on Schliemann (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1993).

22

It was only in 1882 during excavations that architect Wilhelm Dörpfeldw invited to reconstruct urban planning of different periods of the Troy history explained that to Schliemann. After having spent four days in his tent in silence, Schliemann acknowledged that his colleague was right.

23

In 1876 Russian Archaeological Society was trying to buy Schliemann’s collection. However, the price was unaffordable.

24

After the exhibition several countries claimed “the treasures of Priam”: Germany (who received it as a gift), Turkey (where they were found), and even Greece (where they had supposedly belonged).

25

Carl Blegen, Troy and the Trojans.

26

Carl Blegen, Troy and the Trojans.

27

Etymologically the name Hesion associated with the word Asia. Hesion – asiyka, a resident of Anatolia. (L.A. Gindin, V.L. Tsymbursky, Homer and the history of the oriental Mediterranean (Мoscow: Vostochnaya Literature, 1996); p. 53).

28

When she became the wife of Telamon, Hesion bore Teucer, who thus became the half-brother of Ajax Telamonid.

29

Carl Blegen, Troy and the Trojans.

30

C. Baikouzis, M.O. Magnasco, “Is an eclipse described in the Odyssey?” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, June 24 (2008). URL: http://www.pnas.org/content/105/26/8823.full

31

Carl Blegen, Troy and the Trojans.

32

A. Furumark, Mycenaean Pottery I: Analysis and Classification (Stockholm, 1941).

33

Carl Blegen, Troy and the Trojans.

34

Carl Blegen, Troy and the Trojans.

35

Strabo, Geography, XIII, 25.

36

Strabo, Geography, XIII, 27.

37

Strabo, Geography, I, 2.

38

R.V. Gordeziani, Issues of the Homeric Epos (Tbilisi, Tbilisi University Publishing House, 1978); p. 161.

39

Michael Wood, In Search of the Trojan War (Plume, 1987).

40

Lord Byron, Journals, jan. 11, 1821.

41

R.V. Gordeziani, Issues of the Homeric Epos; p. 162.

42

Perhaps the first guess about the difference between time of Homer’s world and the time described in Iliad was made at the beginning of the 18[[th]] century by Giambattista Vico, an Italian philosopher (See Vico, Giambattista. The New Science, III).

43

During his expedition Parry had written down a poem of a Bosnian Avdo Međedović The Wedding of Meho Smailagić that had more than 12,000 lines, that is equal to the volume of the Odyssey. (Albert B. Lord, The Singer of Tales (Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press, 1960)). This was the proof of the possibility of a similar volume of works in the unwritten culture.

44

Albert B. Lord, The Singer of Tales.

45

Marcel Mauss, The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies (London: Cohen&West, 1970).

46

Palace at Pylos, where they found the tablets with texts written with this type of writing, was opened in the early 1950s by Carl Blegenom.

47

M. Ventris, J. Chadwick, “Evidence for Greek dialect in the Mycenaean archives”, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 73 (1953); pp. 84–103.

48

John Chadwick, The Decipherment of Linear B (Cambridge at the University Press, 1967).

49

Paul Faure, La Grèce au temps de la Guerre de Troie. 1250 avant J.-C. (Paris, Hachette, 1975).

50

The leader of the Achaeans Agamemnon makes key decisions not on his own, but at the Military Council. See Iliad, II, 50–444.