Полная версия

Empty Hand

The original Okinawan karate developed in particular during two periods of prohibition of weapon use. After Lord Oho (Shō) Hashi (1372-1439) had unified the country, King Oho (Shō) Shin (1465-1526) had the local gentry disarmed and he forced them to settle in the castle town of Shuri. Furthermore he created a central government and introduced a legal system.

In 1609, almost one and a half centuries after the first prohibition of weapons the Shimazu clan conquered the Ryūkyū islands. These samurai came from southern Kyūshū, from the province of Satsuma. Again the possession of any weapons was forbidden on pain of death for the islanders. Under these circumstances, the development of fighting techniques had to focus on unarmed fighting. So, under the influence of Chinese kempō the Ryūkyū kempō was developed, the archetype of present-day karate.

If the possession of weapons had also been forbidden on mainland Japan, methods of unarmed fighting similar to karate would probably have been developed there, too. If on the other hand the possession of weapons had been allowed to the people of the Ryūkyūs, techniques assisting sword fighting similar to the Japanese jūjutsu might have been developed. So a unique and pure method of unarmed fighting emerged on Okinawa about which in 1934 my father wrote the following sentences in the prologue to his book Introduction into Attack and Defense Techniques in Karate Kempō «30.

In the southwest of Japan there is a chain of islands stretching in the open sea (Jpn. oki) like a rope (Jpn. nawa). So the name of the islands of Okinawa means “rope in the open sea”. Since ancient times these islands have been famous as a strongly armed country without weapons. Because its only weapons are the karate fighting techniques.

Karate – the Fundament of Martial Arts

My father used to say: “Karate is the legitimate heir of the bujutsu martial arts.”31 I think that karate is in fact the basis of all budō fighting techniques. There are two reasons for this statement. First, fighting with nothing but the empty hands is the most elementary way of fighting. Furthermore it is justified to say that any weapons, from staff, sword, bow and arrow or gun up to present-day missiles, could be regarded as extensions of the hand.

If one does not have any weapons one has no choice but to fight with empty hands. If a samurai was called to fight against an unarmed opponent, he would lay down his weapons without any hesitation. The tournaments in the Heian and Kamakura periods always started with archery and were followed by spear and sword fighting. When the fights became too violent the opponents got the order: “Attention! Depart!” They had to lay down their weapons and to continue fighting with empty hands.

If forced to fight with empty hands, everything within reach can be used as an assisting fighting tool. That is the logical and historical starting point for the development of the various techniques of armed fighting. Jūjutsu is a technical system to support fighting with a sword or other weapons, whereas karate integrates weapons to support fighting with empty hands. On the Ryūkyū Islands, for centuries several agricultural and other tools have been used to support karate fighting such as staffs (bō), tridents (sai), sticks with a side-handle (tonfa) or segmented staffs (nunchaku).32

There is a second reason for considering karate as the fundament of all budō fighting techniques: There are no forbidden techniques because the aim is to injure the opponent deadly and this aim must be reached unarmed, with empty hands. That is why the whole body is extremely well prepared for fighting. During the prohibition of arms under the Satsuma rule, the old knowledge about how to fight for life and death without weapons was transferred from generation to generation quite exactly, although not in a written form. Karate practice consisted mainly of kata practice which was done alone so that nobody could be hurt and therefore no kicks or thrusts or punches had to be forbidden. So karate became a worldwide unique art of fighting.

In 1938 my father wrote in this context the following:

If there are people who think that under the pretext of physical education kata and kumite should be changed into sports and separated from their bujutsu or martial arts essence just to fit into the modern times, they should be told that they are obviously not realizing that by doing so they are making the first step to commit a very serious mistake, that is they are contributing to the destruction of the original values of karate as bujutsu. Of course in the practice of kata and kumite the movements of the arms and the legs must be evaluated in detail. But this must be done from a martial arts point of view. Rational-physiologically based preparing and supporting exercises to improve the function of the limbs and the inner organs can be integrated in the practice of karate. But no one should think that the martial content of kata and kumite practice could be improved by changing both into sports or enjoyment.

In a certain way my father thus predicted the present form of karate and warned us of this development. The transformation of karate into competitive sports is one of the main topics of this book, too. But before coming to this point, I would like to say something more about the history of karate.

1.2 The Emergence of Karate on Okinawa

The Old Okinawa-te

On Okinawa, three different styles of karate developed in three localities – Shuri, Naha and Tomari.33 The term karate was introduced in the years 1911-1912 when the “Okinawa Boxing” or the “Okinawa Hand” became a compulsory subject at Japanese middle schools.

At first karate was written combining the character for “Tang China” with that for “hand”. The people of Okinawa called their native martial art only “hand” (te), and the Chinese kempō was called tō-de i.e. “Tang Chinese hand”. The three local styles were called Shuri style, Naha style and Tomari style, or Shuri-te, Naha-te and Tomari-te, respectively. The oldest one was the Shuri-te. This is an original Okinawan system of hand-fighting techniques which took an independent development nourished by Chinese kempō. There was a saying among the Okinawa karate masters: “The only true hand (te) is the Shuri-te.”34 The youngest style is the Naha-te in which the Chinese kempō is preserved most obviously. The Tomari-te is somewhere in between, geographically as well as technically.

Thanks to the recommendation of an acquaintance of the family my father was allowed to join the dōjō of the great master of the Shuri-te Itosu Ankō when he was 13 years old. Many of the famous karate personalities who contributed to the creation of modern karate came from the school of Master Itosu. He was said to have hit the makiwara (rice straw that is bound together in bundles and attached to a wooden post or board) every day several hundred times according to a schedule he had fixed in the morning in order to harden his fists which in the end looked like black stones. A lot of stories were told about the very muscular body of Master Itosu. His upper arm, when being hit with a thick wooden pole did not even quiver when the pole bounced. He could smash a big bamboo cane in his hand or move hand over hand along a ceiling beam across the room without any effort.

In those days karate was not as popular as today and the rooms for practice (dōjō) were rather simple. Quite often the own garden was used as a dōjō and practice was done in open air. As a child I often watched my father exercising in the garden in the light of a bare bulb hitting the makiwara and hardening his muscles with stone weights.

Master Itosu’s dōjō was not open for everybody. Only very selected persons were taught by him. When my father became 19, Master Itosu allowed him to get lessons from Higaonna Kanryō (1853-1916), who was a famous master of the Naha-te. As a young man Higaonna had traveled to the Chinese province of Fukien and studied there the local kempō. After his return to Okinawa he created the Naha-te based on his studies in China. My father was introduced to Higaonna by Miyagi Chōjun (1888-1953), who later founded the Gōjū ryū. Both became favorite students of Master Higaonna and were called “Dragon and Tiger”, and a lifelong friendship developed between them.

Besides the Shuri and Naha styles, my father also studied the Tomari-te and traditional techniques of the Ryūkyū kobudō. He learned bō techniques from Master Aragaki Seichō (1840-1920), knife techniques from Tawada Shinkatsu (1851-1920) and special bō techniques from Master Soeishi Yoshiyuki.

The Kata of the Shuri-te

Karate is a system of self-defense techniques which have been developed on Okinawa since the 17th century at the beginning of the Tokugawa era and passed on secretly to the following generations. It was used to fight with empty hands against opponents armed with swords and other weapons in times when the lords of Satsuma ruled over the Ryūkyū Islands and did not allow the natives to possess weapons and suppressed any resistance. That is why in Ryūkyū kobudō only agricultural tools were used as weapons.

Furthermore, and unlike to the sword techniques or jūjutsu, which were supported by the Tokugawa government in Edo and by the daimyōs in their fiefs, no written records existed about karate. The masters of karate had to transform the technical experience and ideas they had acquired in many dangerous situations into kata, i.e. certain sequences of movements that were rather different of those practiced in other martial arts. They looked similar to traditional Okinawa “boxing dances” called genkotsu odori. Punches, kicks and blocking techniques are carried out as a sequence of attack and defense movements against an imaginary opponent. This way of practicing might also have been helpful to camouflage the true character of the exercises. So the kata became the legacy of the Okinawan karate. The karate student acquires the techniques and the spirit of karate by exercising kata. In the old days, learning the te always meant practicing kata. The masters arranged the kata according to their own experience and understanding. The Ishimine no Passai, for example, is suitable for fighting against small opponents. So it can be supposed that master Ishimine was not a small person. There are five different variations of the Passai kata named after Itosu, Matsumura, Matsumora, Tomari and Ishimine.

Except for the great masters Itosu and Higaonna, it was quite normal for a karate master to teach only one kata. Many of the kata used in our days in the Itosu style are named after masters or places they came from like the Chatan Yara no Kōsōkun, Tomari no Passai, Matsumura no Passai and Ishimine no Passai. Tomari is the name of a place.35 Matsumura and Ishimine were martial arts teachers. Chatan Yara no Kōsōkun means the Kōsōkun kata, created by master Yara from the village Chatan. This kata, which recently has become rather popular in competitive karate, is the most representative one for the Shuri-te. However, in the form transmitted by Yara it contains a circle block technique (mawashi uke) which is very typical for the Naha-te. It was modified considerably to be used as a competition kata. Anyway, the legitimate kata of Shuri-te are the ones taught by master Itosu.

The Jigen Sword Technique and the Shuri-te

According to certain recent research, the tao of Chinese kempō are said to be the archetype of karate kata. But although certain similarities may be found in the tao, karate is – technically and spiritually – totally different from Chinese kempō. This will be explained on the following pages.

As mentioned above, all Okinawan hand-fighting techniques are based on the two main styles Shuri-te and Naha-te. The Shuri-te was taught as secret knowledge among the Shuri nobility. It was perfected by Matsumura Sōkon (1800-1896), the incomparable master of the fist. His teacher was Sakugawa Shungo (1733-1815), who was known in Shuri as an outstanding martial arts expert. He had studied the Chinese kempō (tō-de) in China and passed his knowledge on to the Shuri nobility. That is how he earned the name Tōde Sakugawa. He had learned the northern Peking style which some people think to be the archetype of the Shuri-te. At the age of 20 Matsumura was sent by the Ryūkyū court to the Satsuma province in southern Kyūshū. There he learned the Jigen sword technique and reached the highest level of perfection called unyō (flame cloud). At the age of 27 he returned to the Ryūkyū islands and soon had the opportunity to travel on board of a tribute ship to China. So he could study Chinese kempō in Peking.

In the Jigen ryū there are no upper, middle and lower positions of the sword but only one position called hassō. The sword is raised as if to thrust into the sky. Then, with a bloodcurdling kiai36, one makes a step forward or lowers the stance, crashing the tachi sword down.

The philosophy of the Jigen sword technique demands full control of the oncoming situation and the readiness to win with the first strike. Kondō Isamu, member of the Shinsen gumi37, remembered that there was nothing they were more afraid of than this first strike by the Satsuma men using the Jigen sword technique and that they were repeatedly instructed to evade it. During the war to overthrow the Tokugawa government in 1868 as well as during the samurai rebellion against the new Meiji government in 1877, the Satsuma samurai were feared because of their first strike technique that intimidated their enemies whose corpses were often found cut open by a “sash strike” from the shoulder to the navel. Some even had the guard of their own sword stuck between the eyebrows. They had tried to stop the Satsuma sword by raising their own sword above their heads. But they had underestimated the speed of attack by far so that the defending sword was smashed into the defender’s skull.

The Jigen sword technique was aiming at the highest speed of impact. The highest level of perfection was called flame cloud. This is described in the Manual of Jigen Style Military Techniques as follows: “One eighth of a minute is a byō. A tenth of a byō is called shi. A tenth of a shi is a kotsu. A tenth of a kotsu is a kō. A tenth of a kō is called rin. When one has reached rin this level is called ‘Cloud of Flames’ (unyō).”

The masters of the Jigen style were said to be able to cut raindrops falling from the roof three times before they hit the ground. To train the mental concentration necessary to carry out such ultra high-speed strikes, a special training method was used called “hitting a standing tree” (tachi ki uchi). Partner exercises were not part of the training. Instead, a branch of a Yusu tree was cut and used as a wooden sword to hit a wooden block diagonally from left to right with a loud kiai. “Hitting a standing tree” became the incentive for master Matsumura to invent the training method “hitting the punching board” (makiwara zuki), which is still widely used in traditional karate. As mentioned above, master Itosu, who had been taught by master Matsumura, practiced this on a regular basis38

Master Nakayama Hiromichi (1869-1958), who was called the “Musashi of the Shōwa period” or the “Last of the Sword Saints”, wrote the following words: “Karate turns the empty hand into a sword. This is not a mere metaphor. The karate fist is definitely a sword.”

In historical plays or movies one can often see the opponents hitting each other fiercely and endlessly. Japanese call this chanbara.39In reality this is only possible if the opponents are wearing head and body protectors like in kendō, hitting each other several times while always keeping the right distance. In case of a real fight, the moment when the sword is drawn is decisive for victory or defeat. The first strike will decide whether one will die or live on. There is no second chance. Even if the first strike does not contain the energy of a Jigen strike, it will be deadly.

The fact that master Matsumura perfectly mastered the Jigen sword technique, the favorite style of the Satsuma samurai, has decisively marked the development of the Shuri-te. These samurai who occupied Okinawa since 1609 were the enemies each native Okinawan had in mind while practicing the hand fighting techniques. There is no doubt that it was master Matsumura who shaped karate according to the basic principle to kill the enemy with the first punch or kick.

The masters of Shuri-te took up the idea of a “deadly first strike”. But there is no such idea in Chinese kempō where the ruling principle is called “searching for the hands and legs” (tanshu tantai), that is first testing the technical abilities of the opponent and studying each other. The opponents begin from higher positions (kamae), reduce the distance step by step and finally adopt lower kamae. After each clash the opponents retreat. Then they approach and fight again so that in this way a rather spectacular and dramatic action develops. But this is only possible because in Chinese kempō the empty hand is not a sword.

On the opposite, karate is a martial art developed to defend oneself against an enemy who could be assumed of being educated in the Jigen style and able to carry out the first strike on the “cloud-of-flames” level. It was a question of survival to correctly evaluate the first strike of the swordsman and at the same time to instantly perform the deadly strike. So it can be said that master Matsumura and master Itosu perfected the Shuri-te under the influence of the Japanese sword techniques, in particular that of the Jigen style.

Drawing a Circle With a Straight Line

In Chinese kempō, the basic movement is the circle. In boxing and kickboxing, too, all kicks and punches are carried out as circular movements. Under the influence of these techniques in the post-war era, the karate movements have become circular, too.

Some time ago a student showed me a book titled The Secrets of Okinawan Karate: Essence and Techniques written by Arakaki Kiyoshi. This author also had edited writings left by my father in the monthly journal Karate Dō as a series titled Karate Sankoku Shi. His book was very interesting to me. He wrote: “The essence of Japanese budō can be described as drawing a circle with a straight line.” I was very impressed by this sentence because it expresses with words what I feel with my whole body. In iaidō40 it can be well observed that the arms are drawing a straight line forward while the sword is carrying out a circle. That means that a straight line describes a circle. It is also true that the Jigen ryū “flame cloud” speed that is reached when the sword hits the target cannot be obtained with a circular movement alone. According to master Arakaki, the maximum energy generated by the circular motion is transferred to the target via a straight line that is the shortest possible distance. This technique of the Japanese budō represents the highest level of body perfection.

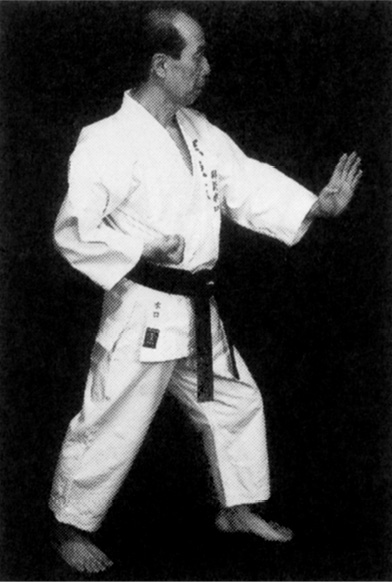

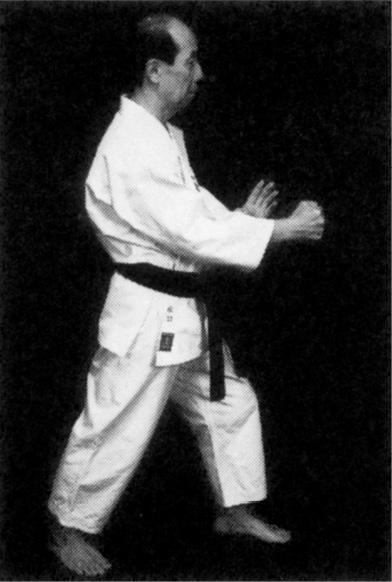

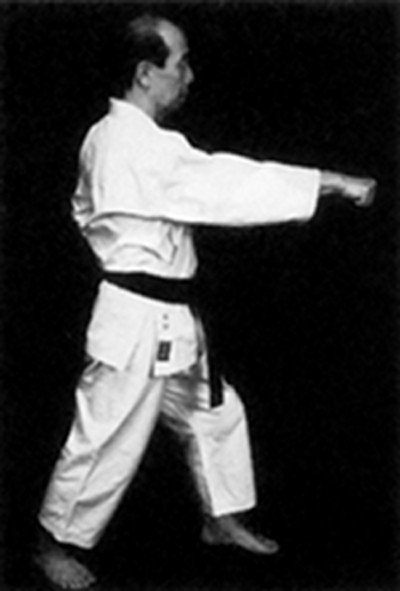

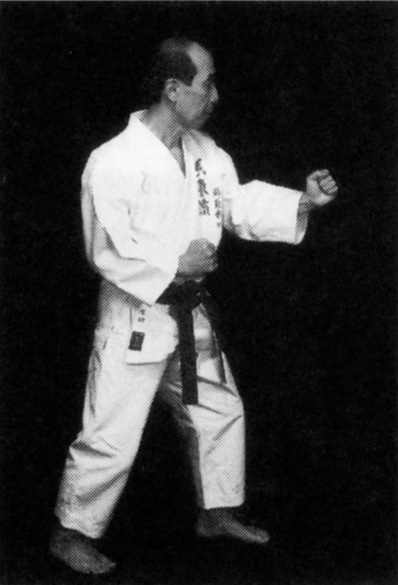

Photos 5 to 7: The execution of a punch. The fist is in the back position close to the hip (hikite) (5). It comes from the hikite position (6), and a thrust is carried out in an absolutely straight line (7).

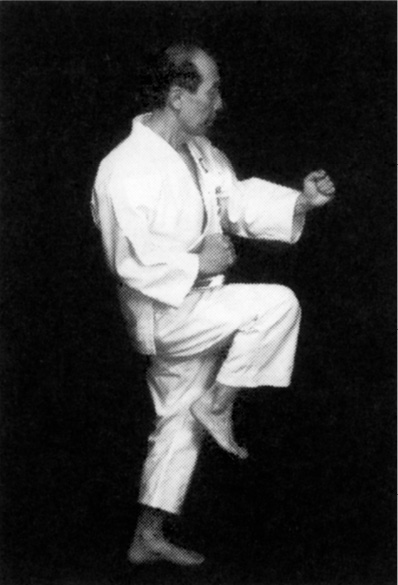

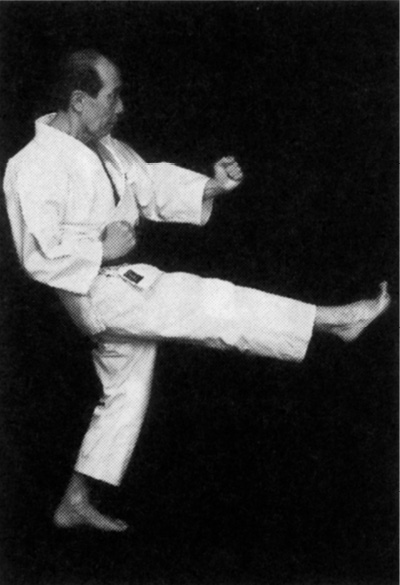

It is not the hardening of the hands and their transformation into weapons what makes the difference to Chinese kempō. It is the kind and perfection of body control in the moment of thrusting and kicking which mobilizes the whole body. When we observe the thrust movement of the fist, we can see that unlike the curved line in boxing, the thrust is carried out in an absolutely straight line by bringing the fist forward out of its back position (hikite) (see photos 5 to 7). Kicking too, is not carried out in wide curved lines or circles as in Chinese kempō or in kickboxing. The karate kick goes straight into the target. Therefore the energy is generated from a circular movement by bending the leg inwards and swinging it up. Then the circle is drawn with a straight line (see photos 8 to 10).

Photos 8 to 10: Execution of a kick. Taking the basic position or ready stance (kamae) (8). The leg is bent and then swung upwards (9). The kick is carried out in a straight line (10).

It may be surprising, but in the traditional karate kata there is no roundhouse kick (mawashi geri) and no kick in the upper level (jōdan geri). However, there are jumped kicks (tobi geri), but they are only used as final falling or sacrifice techniques (sutemi). Kicking in wide, curved lines causes instability because it opens the own weak points to the enemy. It is too slow when fighting against a swordsman or other armed opponents and does not provide deadly first strike ability. Besides this, kicking may easily become ineffective if the opponent is physically stronger.

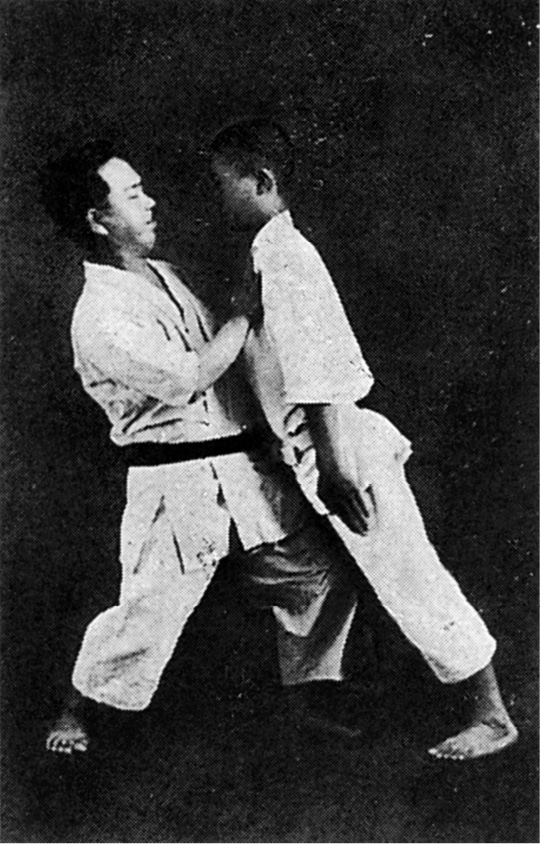

Photo 11: Mabuni Kenwa and his son Kenei practicing the exercise “falling tree” (tōboku hō).

There is a special Japanese budō exercise called “falling tree” (tōboku hō) or “falling down” (tōchi hō). In the book cited above The Secrets of Okinawan Karate by master Arakaki there is a photo showing me doing this exercise. The photo has been taken from the book my father published in 1938, Introduction into Attack and Defense Techniques in Karate Kempō. It shows how my father is supporting or catching me, respectively. This exercise gives the experience of a tree falling down to earth using the energy of the free fall. The body does not try to resist gravity. Arakaki considers this exercise, which is peculiar to the Japanese budō, to be the top level of human body control. My understanding of this practice is not that much scientific and I like to use the name used in the Itosu style: “borrowing power from the earth”.

The beginners in the Itosu ryū always start their studies with the kata of the Shuri-te. “Borrowing power from the earth” is one of the exercises of the traditional Okinawa-te, which is the kernel of the Shuri-te. All Shuri-te kata include the principle of the “falling tree”. Whether this principle is integrated into present-day karate is a point I would like to write about later in the context of the development of karate into a kind of competitive sport.