Полная версия

Dinosaurs

COPYRIGHT.

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street,. London SE1 9GF.

WilliamCollinsBooks.com.

First published in 2006.

This edition published in 2014.

Text © 2006 Douglas Palmer.

Illustrations © 2006 HarperCollins Publishers.

The author asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Illustrations by James Robins and Steve White (pages 10, 13, 18, 21, 23, 25, 27, 28, 31–33 only)

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007222537.

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2019 ISBN: 9780007555277.

Version: 2019-11-29

NOTE TO READERS.

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your e-reader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height.

Change of background and font colours.

Change of font.

Change justification.

Text to speech.

How to use Collins Gem Dinosaurs.

You may choose to read this ebook in a linear fashion, or to explore the information by using the easy-to-use navigation menus, which organise the dinosaurs by period and group.

Note: A few of the dinosaurs detailed in this ebook belong to more than one period on the timeline. These dinosaurs have been categorised in the predominant period.

CONTENTS.

Cover. Title Page. Copyright. Note to Readers.

INTRODUCTION.

WHAT IS A DINOSAUR?. DINOSAUR APPEARANCES.. DINOSAUR BEHAVIOUR.. DINOSAUR DIETS.. EGGS, NESTS AND BABIES.. THE ARMS RACE.. TRACKS AND TRAILS.. THE DINOSAUR ERA.. FOSSIL FORMATION.. THE FIRST FINDS.. DINOSAUR NAMES.. ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION.

THE DINOSAURS.

GLOSSARY.

WEBSITES AND FURTHER READING.

INDEX.

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION.

To most people, the word dinosaur brings to mind an enormous animal of awesome strength and ferocity. The name dinosaur means ‘terrible lizard’, and thanks to a constant deluge of dinosaur images in popular media, these amazing extinct animals have become perhaps the most iconic creatures in history.

What is less often apparent is the extraordinary diversity and variety of the dinosaurs. They were not all vast meat eaters and some resembled birds more closely than the reptiles we know today, with feathers rather than scaly skin. This introduction to dinosaur life portrays a selection of the dinosaurs we know most about, from the earliest ones, such as Eoraptor that lived around 228 million years ago, to the latest ones, such as Triceratops that became extinct 65 million years ago. We discover what they were like, where they lived, how they behaved, when they were first found and what the most recent discoveries tell us. Also included is information on what their names mean and how to pronounce them.

The popularity of dinosaurs has boomed since the early decades of the 19th century, when fossils of these extinct prehistoric monsters were first discovered and portrayed as once living animals. Yet despite the efforts of dinosaur experts over the last 200 years, we still have just a small sample – some 600 different kinds (genera) – of the total range and diversity of these remarkable animals, which dominated life on land for the best part of 100 million years.

As a result of this, many questions remain unanswered about how they lived, where they came from and how they were related to one another. For example, were the giant meat-eating theropods active hunters that chased down their prey, or were they scavengers who used their size to chase other meat eaters away from their kills? And did the giant plant-eating sauropods continue growing over a long period or did they grow faster than many of the large animals that are alive today? There is still much to be discovered, and who knows, maybe one day you will be the one to answer some of these questions.

WHAT IS A DINOSAUR?.

Since the early decades of the 19th century, fossil hunters have dug up hundreds of different kinds of ancient reptiles that we now know as dinosaurs. From tiny bird-sized creatures to the largest animals ever to have lived on land, the dinosaurs were an extraordinary group of animals. Ancient peoples populated their myths and legends with all sorts of strange monsters such as dragons. Today, the role of these creatures has been filled by the dinosaurs – real animals, many of which were just as strange as any fictional beast.

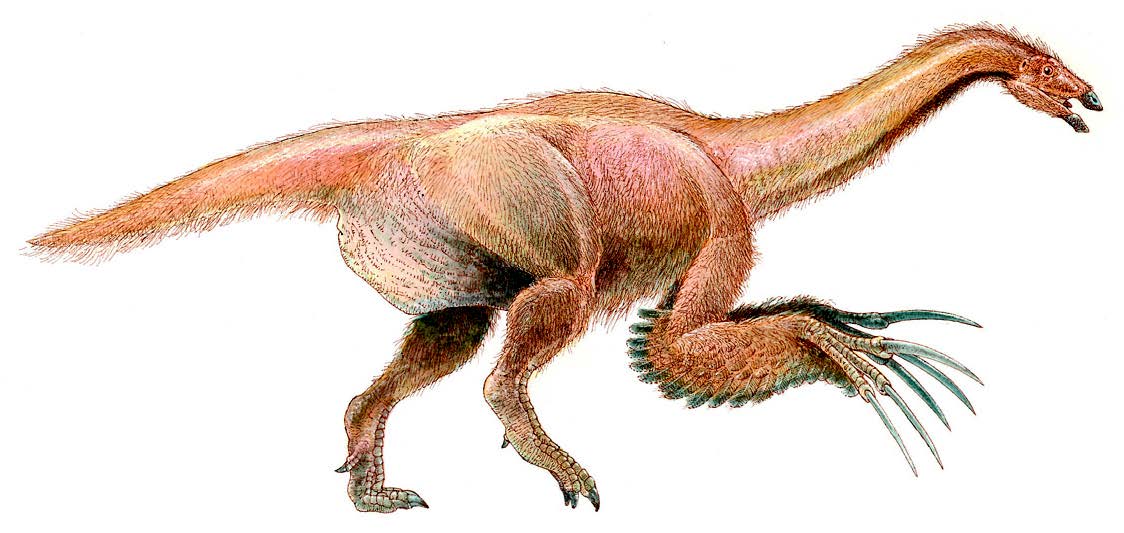

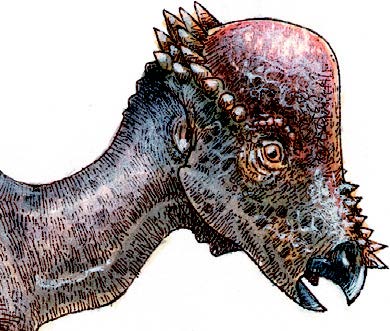

Caption:

Therizinosaurus, fantastic fiction or actual dinosaur?

The dinosaurs first appeared around 230 million years ago and altogether form a special group of reptiles with certain distinct characters that were first recognized in the mid-19th century by the English anatomist Richard Owen. These features are preserved in the structure of their skeletons, especially their hip bones, and they separate dinosaurs from other reptiles both living and extinct. A number of extinct and distant reptile relatives of the dinosaurs, such as the flying pterosaurs and the sea-dwelling ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs, are often described as if they were dinosaurs, but this is not the case.

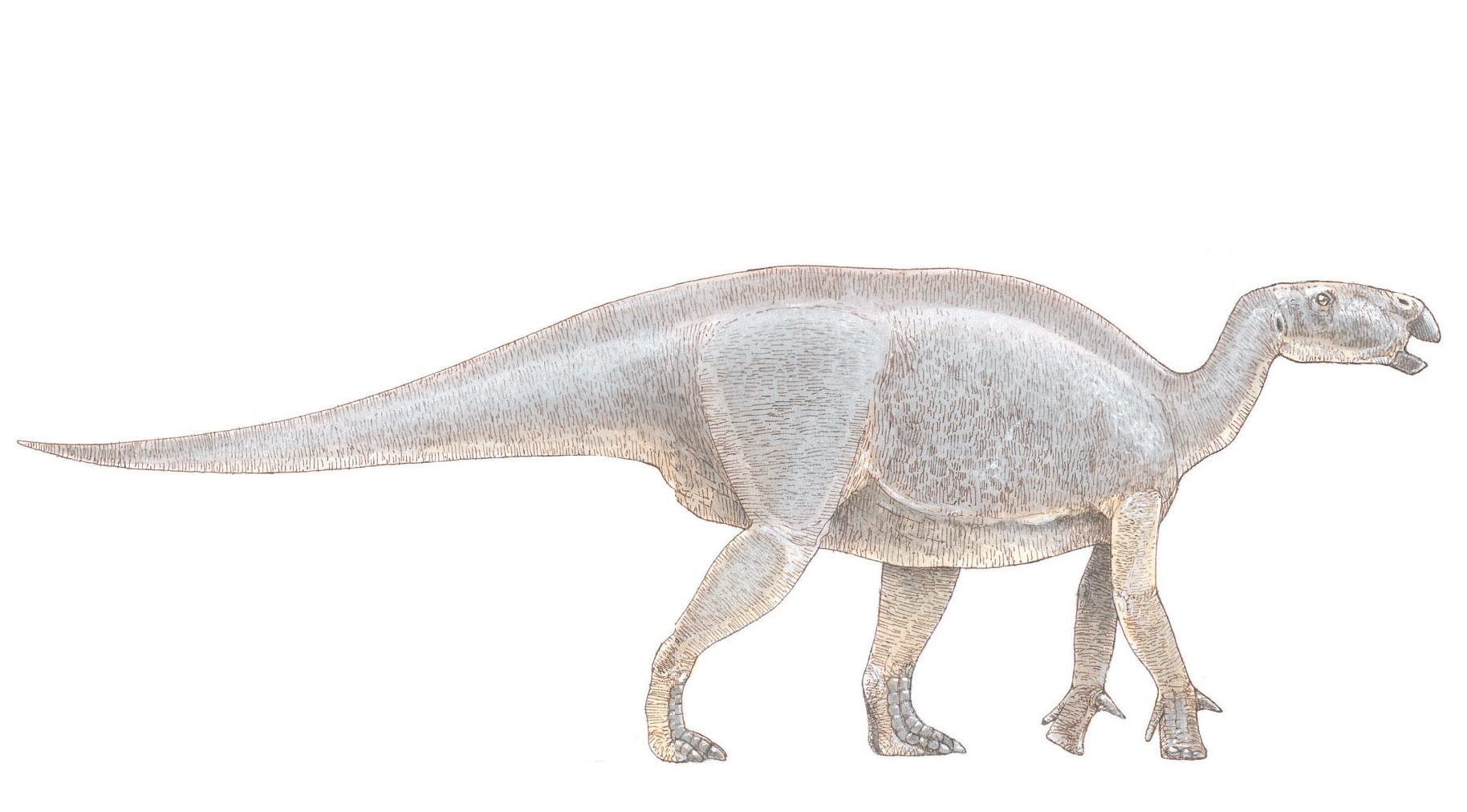

Caption:

Iguanodon, first described by Gideon Mantell.

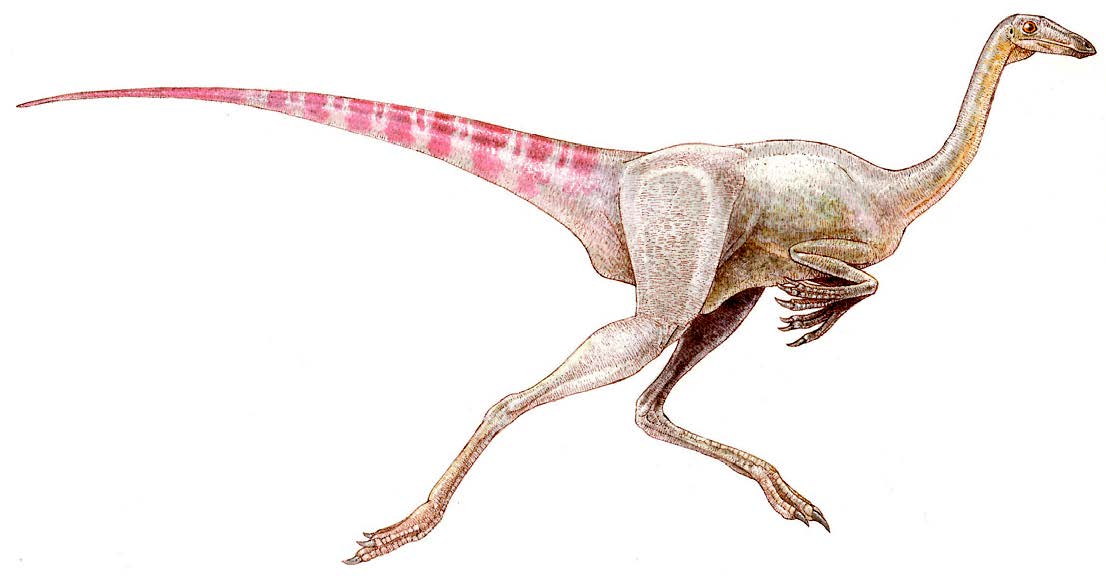

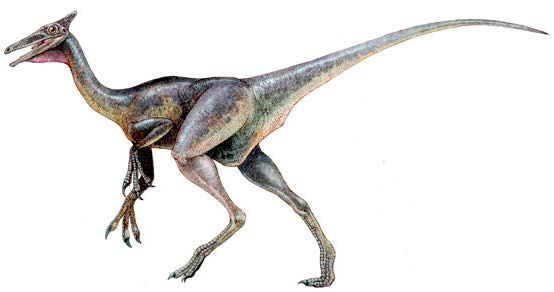

Caption:

Ornithomimus, a small and agile Ostrich-like dinosaur.

Caption: A crocodile, a living relative of the dinosaurs.

The closest living relatives to the dinosaurs are the birds and crocodiles, with which they share certain features. All three groups share the presence of extra openings in the skull and jaw. With the birds they have in common lightly built bones, the bony structure of their legs, a hinged ankle, and aspects of the skull and jaws. And while the dinosaurs are also similar to crocodiles, they differ from them and other reptiles in the bone structure of their legs, feet and hips. Crocodiles, like most other living reptiles, sprawl with their limbs held out to the side of the body. However, the dinosaurs have their limbs tucked in under the body, a structure that allows them to walk and run more efficiently.

The image and idea of dinosaurs as once living animals has changed enormously since their fossil remains were first discovered and recognized as belonging to a distinct group of extinct reptiles. Even the iconic status of the giant meat eaters like Tyrannosaurus rex has been partly displaced by that of small, fast-moving and highly active predators, some of which are known to have been covered with hairlike down and feathers.

Caption:

Archaeopteryx, a feathered dinosaur descendant.

DINOSAUR APPEARANCES.

Nobody has ever seen a live dinosaur, so our ideas about what exactly they looked like and how they behaved mostly have to come from our interpretation of their fossil record. Using living reptiles as a model for how dinosaurs might have looked led early investigators astray, because in many ways the dinosaurs were very different from crocodiles and lizards.

Once it was realized that dinosaur skeletons were put together in a rather different way from those of any living animals, scientists had to go back to the basics of anatomy to try to reconstruct what the creatures really looked like. As more and better preserved skeletons were found, many surprise discoveries were made. Some dinosaurs – for example, sauropods such as Diplodocus – were immense, with massive bodies supported on four pillar-like legs; if anything, they resembled large plant-eating mammals. Other dinosaurs were more like birds in that they supported their body weight on their two hind legs. These dinosaurs could be pretty immense, too, especially some of the meat-eating theropods such as Allosaurus.

Accurate reconstructions of the skeletons found have allowed scientists to gain an idea of the size and shape of the 600 or so different kinds of dinosaurs. They can also show how the dinosaurs moved about and, along with the shape of their teeth, indicate how they fed. However, very rarely do fossils tell us anything about other aspects of dinosaurs’ behaviour, such as their breeding or social habits, or the fine detail of their appearance, including the texture and colour of their skin. Surprisingly, however, new discoveries are revealing some of these details to us, as we shall see.

For more than 200 years anatomists have realized that the careful study of the way the bones of a skeleton fit and work together – called comparative anatomy – allows the reconstruction of extinct beasts whose body shape may be quite unlike that of any living animal. The reason for this is that all animals with bony skeletons, from fish to humans (known collectively as the vertebrates), share a common structure. This is still true even when parts of the body perform quite different functions. For instance, the human arm and the wings of birds and bats have a basic structure similar to the front leg of a Diplodocus, the arm of Tyrannosaurus and the paddle of a whale. By assessing the different proportions and structures of fossil bones with equivalent bones in living animals, their functions in the extinct animal can be predicted.

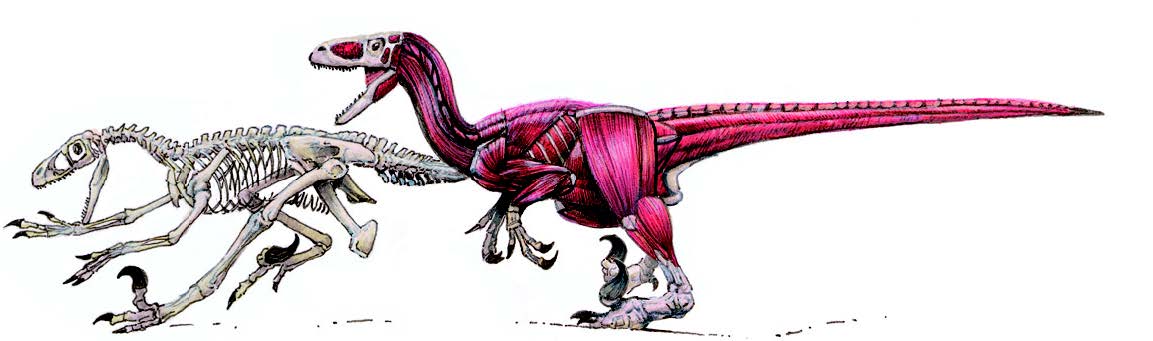

Caption:. Bodybuilding: Velociraptor skeleton and musculature.

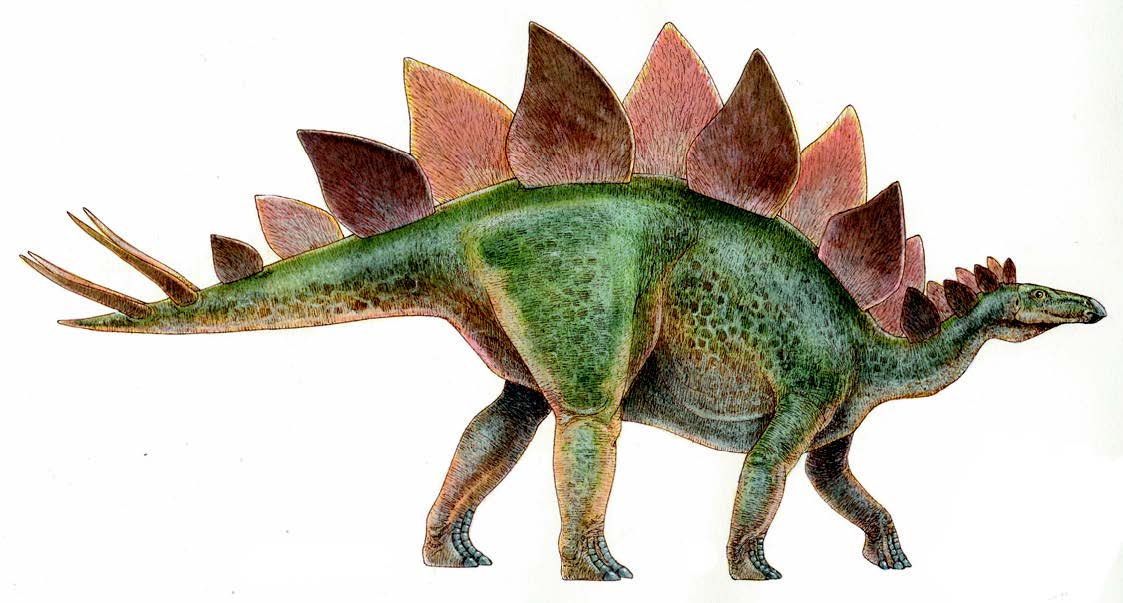

Caption:

Stegosaurus, with its distinctive bony back plates.

Detailed study of fossil bones can also indicate the presence of other features such as where muscles attached and how big they were, and where blood vessels and nerves ran. The thickness of a bone’s wall and its interior structure indicate how strong it was and whether it could carry a heavy body or was instead adapted for swimming or flight.

Sometimes, fossil skeletons are found that are nearly complete and have their various bones still articulated in their true anatomical positions. Such discoveries have helped confirm what anatomists have predicted, but they have also sometimes led to surprises. Some dinosaur structures are so original and unusual that they cannot easily be predicted by comparative anatomy. For instance, what exactly the back plates of a Stegosaurus and the hand claws of a Therizinosaurus were used for is still something of a puzzle.

Very occasionally, imprints or mineralized soft tissues are preserved that show that a particular dinosaur had a scaly skin or a feather-like covering. Even internal organs such as the gut and stomach contents have been preserved in some instances, giving important clues as to how the animals lived.

Caption:

The dome on the skull of Pachycephalosaurus could be up to 25cm (10in) thick.

DINOSAUR BEHAVIOUR.

Much of our understanding of dinosaur behaviour is based on our knowledge of their body form and feeding habits – whether they were plant eaters (herbivores) or meat eaters (carnivores). Knowledge of how different kinds of living plant eaters interact with their meat-eating predators can give insights into how the dinosaurs interacted. Like herbivorous mammals today, many plant-eating dinosaurs tended to have good senses of sight, smell and hearing. To escape their predators, some were slimly built and fleet of foot. Others had heavy defensive armour and yet others sought safety in numbers. The meat eaters were well equipped with offensive weapons such as large, sharp teeth and claws, and were either fast on their feet, large and stealthy or good ambush hunters.

The study of dinosaur feeding behaviour was originally based on that of large living reptiles such as crocodiles. However, this was somewhat misleading as crocodiles, with their relatively small limbs, largely live in water and can survive on infrequent feeds. Relating other aspects of crocodile behaviour to dinosaurs proved equally mistaken. Crocodiles, for example, belong to the group of animals known as ectotherms, which rely on the sun’s rays to heat their bodies. In contrast, endotherms (which include mammals) use energy from frequent supplies of nutritious food and complex blood systems to maintain a relatively high body temperature. It was once thought that all dinosaurs were crocodile-like ectotherms, but we now know from several different lines of evidence, such as their bone structure, that some dinosaurs may have been endotherms. Consequently, their levels of activity and feeding were probably more like those of mammals than ectothermic reptiles living today.

We can now envisage many land-living predatory dinosaurs as active hunters that could run at speeds of up to 40kph (25mph) to catch their prey. Some predators may even have worked together in groups to kill prey larger than themselves, and some were cannibals. Many of the larger herbivores lived in herds so that their many combined eyes, ears and nostrils could provide early warning of approaching predators. But how do we know what dinosaurs ate?

Caption:

Pelecanimimus had a relatively large brain and unusually small teeth.

DINOSAUR DIETS.

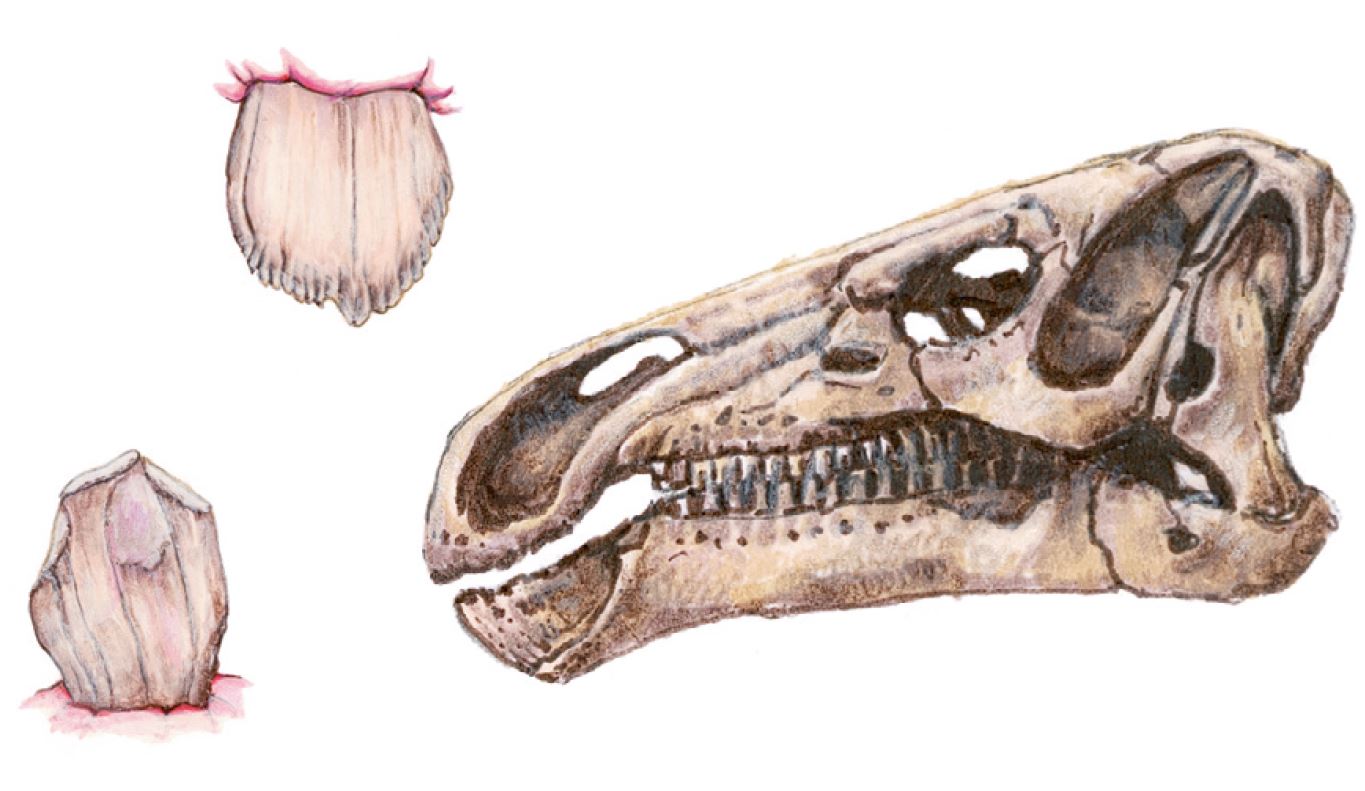

The most important clues as to what dinosaurs ate are provided by their teeth. Typically, the teeth of dinosaurs (like those of other reptiles) were constantly replaced from within the jaw throughout the animal’s life.

The types of food an animal eats determine the type of teeth it requires. Meat eaters need sharp, dagger-like and blade-shaped teeth for killing their prey and tearing pieces of meat from the carcass. There are, however, further differences within this group depending upon whether the prey consists of insects, fish, small mammals or large, well-defended, aggressive plant eaters or other meat eaters.

Caption: Meat-eaters: a Tyrannosaurus rex skull and its cutting teeth.

Small insect-eating dinosaurs, for example, needed only small, sharp, conical teeth that were strong enough to crunch the insects up. In contrast, large predatory dinosaurs that required lots of meat had large teeth that were powerful and sharp enough to kill their prey and then remove as much flesh as quickly as possible before other predators and scavengers were attracted to the kill. Some of these teeth had sophisticated cutting edges with serrations like those on a steak knife.

Plant-eating dinosaurs displayed an even greater variety in the form of their teeth depending upon the kind of plant material they ate. Many of the giant sauropods had strange peg-like teeth that probably worked like rakes, stripping large amounts of foliage from branches as the animal’s long neck swept from side to side and up and down. Other herbivores ate much tougher fibrous plants and had large, strong, leaf-shaped teeth that were gradually worn away and eventually replaced.

Since flowering plants did not evolve until Cretaceous times around 100 million years ago, the food available to herbivorous dinosaurs included more basic groups of plants such as ferns, conifers, cycads, horsetails and ginkgos. Many of these plants were difficult to digest and had low nutritional value. Like many herbivorous mammals today, the plant-eating dinosaurs had large stomachs and had to eat constantly to obtain enough nutrition from their diet. As an aid to digestion, some of them swallowed stones that then acted as a gastric mill along with their stomach flora of digestive bacteria. But large size slows an animal down, so how did the giant herbivores protect themselves from predators?

Caption:

Plant-eater: Iguanodon and details of its grinding teeth.

EGGS, NESTS AND BABIES.

Fossil eggs, now known to be those of dinosaurs, were first found in France and England in the mid-19th century. But it was not until the amazing discoveries of the Roy Chapman Andrews’ expedition to Mongolia in the 1920s that we really began to get an idea of how dinosaurs reproduced in bird-like ways and how some of them looked after their babies.

Chapman and his team from the American Museum of Natural History in New York found fossil eggs and hatchlings clustered together in and around mud mounds. They even thought that they had found the remains of a dinosaur egg thief called Oviraptor in the act of stealing from a Protoceratop’s nest. However, we now know that it is more likely that the Oviraptor died defending its own nest.

Caption: A nesting Psittacosaurus dinosaur with babies.

Dinosaur eggs ranged in size and shape from tiny round eggs to long oval-shaped ones more than 50cm (20in) long and around 4.0l (8.5pts) in volume. These were, however, small compared to the biggest bird egg, which was laid by the extinct Elephant Bird (Aepyornis) and measured more than 1m (3ft) in circumference and 7.3l (15.4pts) in volume. Large eggs need thick shells but these also have to be porous to allow the foetus to ‘breathe’. Consequently, dinosaur eggs could not be too large. Like modern- day turtles, many dinosaurs laid large numbers of eggs because relatively few of the babies would survive into adulthood.

In the 1970s, finds from the so-called Egg Mountain site in Montana, USA, revealed what may have been a shared nesting ground and hatchery for the duck-billed dinosaur Maiasaura. Several nests up to 2m (6.6ft) wide have been found, made of layers of plant material and mud topped by a hollow in which up to 12 eggs were laid. The 9m-long (30ft) mother was far too big to have sat on the eggs but probably would have fed her babies, which could not have looked after themselves to begin with.

In contrast, hatchlings of the small theropod Troodon, which also nested around Egg Mountain, were much more precocious and probably began to feed themselves very early on. Surprisingly, there is evidence that even some of the biggest plant-eating sauropods stayed around their nests for some time, presumably to try to protect the eggs and babies from predators.

Caption: A Mussaurus hatchling. Some of the skeletons of this species could fit into the palm of a hand.

THE ARMS RACE.

There are a number of reasons why animals, and even humans, fight one another. Disputes over food, territory and mates commonly lead to conflict, and dinosaurs were no exception to the rule. However, our understanding of dinosaur disputes is biased by what information we can recover from the fossil record and what can be inferred from general principles of animal behaviour.

Obviously, the main arena of conflict results from the predator–prey relationship between meat eaters and plant eaters. Predators have to be appropriately armed to catch and kill their prey and, as we have seen, this is primarily a matter of being able to detect the prey, surprise it and then catch it with claws or teeth. Inevitably, eggs, babies and juvenile dinosaurs would have been most vulnerable to predation. From the prey’s point of view, the matter is largely one of flight or fight – in other words, being able to run away or defend itself.

Some of the small plant-eating dinosaurs opted for the flight mechanism and were fleet of foot. The two-legged ornithomimids, for example, may have been able to run at speeds of up to 40kph (25mph). At the other end of the scale, giant sauropods, once grown up, were so big they would have been invulnerable. Medium-sized but heavy, slow plant eaters such as the ceratopsians, stegosaurs and ankylosaurs evolved a variety of types of armour and defensive weaponry. The ceratopsians are characterized by their helmet-like skulls with prominent rhino-like horns. The stegosaurs had plates and spikes along their back and tail, while the ankylosaurs had tough bony plates embedded in their skin as well as bone-crunching tail clubs. The same weaponry was probably also used by males when fighting one another in territorial disputes or over females. Some of the defensive weaponry that is not as structurally robust as it looks, such as the neck flanges and frills of the ceratopsians, may also have had other functions, such as for male display, signalling and species recognition.

Caption: A Repenomamus with a baby Psittacosaurus.

Medium-sized plant eaters that were neither fast movers nor well armoured developed other means of defending themselves against predators. The hadrosaurs, for example, were equipped with a variety of strange bony structures on their skulls, some of which may have been used to amplify calls to other members of the herd to warm against a nearby predator.

And, finally, we now know that dinosaurs did not have it all their own way. Recently, the fossil of a badger-sized mammal called Repenomamus has been found with the remains of a baby psittacosaur in its stomach cavity.