Полная версия

But Túrin wept bitterly at night alone, though to Morwen he never again spoke the name of his sister. To one friend only he turned at that time, and to him he spoke of his sorrow and the emptiness of the house. This friend was named Sador, a house-man in the service of Húrin; he was lame, and of small account. He had been a woodman, and by ill-luck or the mishandling of his axe he had hewn his right foot, and the footless leg had shrunken; and Túrin called him Labadal, which is ‘Hopafoot’, though the name did not displease Sador, for it was given in pity and not in scorn. Sador worked in the outbuildings, to make or mend things of little worth that were needed in the house, for he had some skill in the working of wood; and Túrin would fetch him what he lacked, to spare his leg, and sometimes he would carry off secretly some tool or piece of timber that he found unwatched, if he thought his friend might use it. Then Sador smiled, but bade him return the gifts to their places; ‘Give with a free hand, but give only your own,’ he said. He rewarded as he could the kindness of the child, and carved for him the figures of men and beasts; but Túrin delighted most in Sador’s tales, for he had been a young man in the days of the Bragollach, and loved now to dwell upon the short days of his full manhood before his maiming.

‘That was a great battle, they say, son of Húrin. I was called from my tasks in the wood in the need of that year; but I was not in the Bragollach, or I might have got my hurt with more honour. For we came too late, save to bear back the bier of the old lord, Hador, who fell in the guard of King Fingolfin. I went for a soldier after that, and I was in Eithel Sirion, the great fort of the Elf-kings, for many years; or so it seems now, and the dull years since have little to mark them. In Eithel Sirion I was when the Black King assailed it, and Galdor your father’s father was the captain there in the King’s stead. He was slain in that assault; and I saw your father take up his lordship and his command, though but new come to manhood. There was a fire in him that made the sword hot in his hand, they said. Behind him we drove the Orcs into the sand; and they have not dared to come within sight of the walls since that day. But alas! my love of battle was sated, for I had seen spilled blood and wounds enough; and I got leave to come back to the woods that I yearned for. And there I got my hurt; for a man that flies from his fear may find that he has only taken a short cut to meet it.’

In this way Sador would speak to Túrin as he grew older; and Túrin began to ask many questions that Sador found hard to answer, thinking that others nearer akin should have had the teaching. And one day Túrin said to him: ‘Was Lalaith indeed like an Elf-child, as my father said? And what did he mean, when he said that she was briefer?’

‘Very like,’ said Sador; ‘for in their first youth the children of Men and Elves seem close akin. But the children of Men grow more swiftly, and their youth passes soon; such is our fate.’

Then Túrin asked him: ‘What is fate?’

‘As to the fate of Men,’ said Sador, ‘you must ask those that are wiser than Labadal. But as all can see, we weary soon and die; and by mischance many meet death even sooner. But the Elves do not weary, and they do not die save by great hurt. From wounds and griefs that would slay Men they may be healed; and even when their bodies are marred they return again, some say. It is not so with us.’

‘Then Lalaith will not come back?’ said Túrin. ‘Where has she gone?’

‘She will not come back,’ said Sador. ‘But where she has gone no man knows; or I do not.’

‘Has it always been so? Or do we suffer some curse of the wicked King, perhaps, like the Evil Breath?’

‘I do not know. A darkness lies behind us, and out of it few tales have come. The fathers of our fathers may have had things to tell, but they did not tell them. Even their names are forgotten. The Mountains stand between us and the life that they came from, flying from no man now knows what.’

‘Were they afraid?’ said Túrin.

‘It may be,’ said Sador. ‘It may be that we fled from the fear of the Dark, only to find it here before us, and nowhere else to fly to but the Sea.’

‘We are not afraid any longer,’ said Túrin, ‘not all of us. My father is not afraid, and I will not be; or at least, as my mother, I will be afraid and not show it.’

It seemed then to Sador that Túrin’s eyes were not the eyes of a child, and he thought: ‘Grief is a hone to a hard mind.’ But aloud he said: ‘Son of Húrin and Morwen, how it will be with your heart Labadal cannot guess; but seldom and to few will you show what is in it.’

Then Túrin said: ‘Perhaps it is better not to tell what you wish, if you cannot have it. But I wish, Labadal, that I were one of the Eldar. Then Lalaith might come back, and I should still be here, even if she were long away. I shall go as a soldier with an Elf-king as soon as I am able, as you did, Labadal.’

‘You may learn much of them,’ said Sador, and he sighed. ‘They are a fair folk and wonderful, and they have a power over the hearts of Men. And yet I think sometimes that it might have been better if we had never met them, but had walked in lowlier ways. For already they are ancient in knowledge; and they are proud and enduring. In their light we are dimmed, or we burn with too quick a flame, and the weight of our doom lies the heavier on us.’

‘But my father loves them,’ said Túrin, ‘and he is not happy without them. He says that we have learned nearly all that we know from them, and have been made a nobler people; and he says that the Men that have lately come over the Mountains are hardly better than Orcs.’

‘That is true,’ answered Sador; ‘true at least of some of us. But the up-climbing is painful, and from high places it is easy to fall low.’

At this time Túrin was almost eight years old, in the month of Gwaeron in the reckoning of the Edain, in the year that cannot be forgotten. Already there were rumours among his elders of a great mustering and gathering of arms, of which Túrin heard nothing; though he marked that his father often looked steadfastly at him, as a man might look at something dear that he must part from.

Now Húrin, knowing her courage and her guarded tongue, often spoke with Morwen of the designs of the Elven-kings, and of what might befall, if they went well or ill. His heart was high with hope, and he had little fear for the outcome of the battle; for it did not seem to him that any strength in Middle-earth could overthrow the might and splendour of the Eldar. ‘They have seen the Light in the West,’ he said, ‘and in the end Darkness must flee from their faces.’ Morwen did not gainsay him; for in Húrin’s company the hopeful ever seemed the more likely. But there was knowledge of Elven-lore in her kindred also, and to herself she said: ‘And yet did they not leave the Light, and are they not now shut out from it? It may be that the Lords of the West have put them out of their thought; and how then can even the Elder Children overcome one of the Powers?’

No shadow of such doubt seemed to lie on Húrin Thalion; yet one morning in the spring of that year he awoke heavy as after unquiet sleep, and a cloud lay on his brightness that day; and in the evening he said suddenly: ‘When I am summoned, Morwen Eledhwen, I shall leave in your keeping the heir of the House of Hador. The lives of Men are short, and in them there are many ill chances, even in time of peace.’

‘That has ever been so,’ she answered. ‘But what lies under your words?’

‘Prudence, not doubt,’ said Húrin; yet he looked troubled. ‘But one who looks forward must see this: that things will not remain as they were. This will be a great throw, and one side must fall lower than it now stands. If it be the Elven-kings that fall, then it must go evilly with the Edain; and we dwell nearest to the Enemy. This land might pass into his dominion. But if things do go ill, I will not say to you: Do not be afraid! For you fear what should be feared, and that only; and fear does not dismay you. But I say: Do not wait! I shall return to you as I may, but do not wait! Go south as swiftly as you can – if I live I shall follow, and I shall find you, though I have to search through all Beleriand.’

‘Beleriand is wide, and houseless for exiles,’ said Morwen. ‘Whither should I flee, with few or with many?’

Then Húrin thought for a while in silence. ‘There is my mother’s kin in Brethil,’ he said. ‘That is some thirty leagues, as the eagle flies.’

‘If such an evil time should indeed come, what help would there be in Men?’ said Morwen. ‘The House of Bëor has fallen. If the great House of Hador falls, in what holes shall the little Folk of Haleth creep?’

‘In such as they can find,’ said Húrin. ‘But do not doubt their valour, though they are few and unlearned. Where else is hope?’

‘You do not speak of Gondolin,’ said Morwen.

‘No, for that name has never passed my lips,’ said Húrin. ‘Yet the word is true that you have heard: I have been there. But I tell you now truly, as I have told no other, and will not: I do not know where it stands.’

‘But you guess, and guess near, I think,’ said Morwen. ‘It may be so,’ said Húrin. ‘But unless Turgon himself released me from my oath, I could not tell that guess, even to you; and therefore your search would be vain. But were I to speak, to my shame, you would at best but come at a shut gate; for unless Turgon comes out to war (and of that no word has been heard, and it is not hoped) no one will come in.’

‘Then if your kin are not hopeful, and your friends deny you,’ said Morwen, ‘I must take counsel for myself; and to me now comes the thought of Doriath.’

‘Ever your aim is high,’ said Húrin.

‘Over-high, you would say?’ said Morwen. ‘But last of all defences will the Girdle of Melian be broken, I think; and the House of Bëor will not be despised in Doriath. Am I not now kin of the king? For Beren son of Barahir was grandson of Bregor, as was my father also.’

‘My heart does not lean to Thingol,’ said Húrin. ‘No help will come from him to King Fingon; and I know not what shadow falls on my spirit when Doriath is named.’

‘At the name of Brethil my heart also is darkened,’ said Morwen.

Then suddenly Húrin laughed, and he said: ‘Here we sit debating things beyond our reach, and shadows that come out of dream. Things will not go so ill; but if they do, then to your courage and counsel all is committed. Do then what your heart bids you; but do it swiftly. And if we gain our ends, then the Elven-kings are resolved to restore all the fiefs of Bëor’s house to his heir; and that is you, Morwen daughter of Baragund. Wide lordships we should then wield, and a high inheritance come to our son. Without the malice in the North he should come to great wealth, and be a king among Men.’

‘Húrin Thalion,’ said Morwen, ‘this I judge truer to say: that you look high, but I fear to fall low.’

‘That at the worst you need not fear,’ said Húrin.

That night Túrin half-woke, and it seemed to him that his father and mother stood beside his bed, and looked down on him in the light of the candles that they held; but he could not see their faces.

On the morning of Túrin’s birthday Húrin gave his son a gift, an Elf-wrought knife, and the hilt and the sheath were silver and black; and he said: ‘Heir of the House of Hador, here is a gift for the day. But have a care! It is a bitter blade, and steel serves only those that can wield it. It will cut your hand as willingly as aught else.’ And setting Túrin on a table he kissed his son, and said: ‘You overtop me already, son of Morwen; soon you will be as high on your own feet. In that day many may fear your blade.’

Then Túrin ran from the room and went away alone, and in his heart was a warmth like the warmth of the sun upon the cold earth that sets growth astir. He repeated to himself his father’s words, Heir of the House of Hador; but other words came also to his mind: Give with a free hand, but give of your own. And he went to Sador and cried: ‘Labadal, it is my birthday, the birthday of the heir of the House of Hador! And I have brought you a gift to mark the day. Here is a knife, just such as you need; it will cut anything that you wish, as fine as a hair.’

Then Sador was troubled, for he knew well that Túrin had himself received the knife that day; but men held it a grievous thing to refuse a free-given gift from any hand. He spoke then to him gravely: ‘You come of a generous kin, Túrin son of Húrin. I have done nothing to equal your gift, and I cannot hope to do better in the days that are left to me; but what I can do, I will.’ And when Sador drew the knife from the sheath he said: ‘This is a gift indeed: a blade of elven steel. Long have I missed the feel of it.’

Húrin soon marked that Túrin did not wear the knife, and he asked him whether his warning had made him fear it. Then Túrin answered: ‘No; but I gave the knife to Sador the woodwright.’

‘Do you then scorn your father’s gift?’ said Morwen; and again Túrin answered: ‘No; but I love Sador, and I am sorry for him.’

Then Húrin said: ‘All three gifts were your own to give, Túrin: love, pity, and the knife the least.’

‘Yet I doubt if Sador deserves them,’ said Morwen. ‘He is self-maimed by his own want of skill, and he is slow with his tasks, for he spends much time on trifles unbidden.’

‘Give him pity nonetheless,’ said Húrin. ‘An honest hand and a true heart may hew amiss; and the harm may be harder to bear than the work of a foe.’

‘But you must wait now for another blade,’ said Morwen. ‘Thus the gift shall be a true gift and at your own cost.’

Nonetheless Túrin marked that Sador was treated more kindly thereafter, and was set now to the making of a great chair for the lord to sit on in his hall.

There came a bright morning in the month of Lothron when Túrin was roused by sudden trumpets; and running to the doors he saw in the court a great press of men on foot and on horse, and all fully armed as for war. There also stood Húrin, and he spoke to the men and gave commands; and Túrin learned that they were setting out that day for Barad Eithel. These were Húrin’s guards and household men; but all the men of his land that could be spared were summoned. Some had gone already with Huor his father’s brother; and many others would join the Lord of Dor-lómin on the road, and go behind his banner to the great muster of the King.

Then Morwen bade farewell to Húrin without tears; and she said: ‘I will guard what you leave in my keeping, both what is and what shall be.’

And Húrin answered her: ‘Farewell, Lady of Dor-lómin; we ride now with greater hope than ever we have known before. Let us think that at this midwinter the feast shall be merrier than in all our years yet, with a fearless spring to follow after!’ Then he lifted Túrin to his shoulder, and cried to his men: ‘Let the heir of the House of Hador see the light of your swords!’ And the sun glittered on fifty blades as they leaped forth, and the court rang with the battle-cry of the Edain of the North: Lacho calad! Drego morn! Flame Light! Flee Night!

Then at last Húrin sprang into his saddle, and his golden banner was unfurled, and the trumpets sang again in the morning; and thus Húrin Thalion rode away to the Nirnaeth Arnoediad.

But Morwen and Túrin stood still by the doors, until far away they heard the faint call of a single horn on the wind: Húrin had passed over the shoulder of the hill, beyond which he could see his house no more.

CHAPTER II

THE BATTLE OF UNNUMBERED TEARS

Many songs are yet sung and many tales are yet told by the Elves of the Nirnaeth Arnoediad, the Battle of Unnumbered Tears, in which Fingon fell and the flower of the Eldar withered. If all were now retold a man’s life would not suffice for the hearing. Here then shall be recounted only those deeds which bear upon the fate of the House of Hador and the children of Húrin the Steadfast.

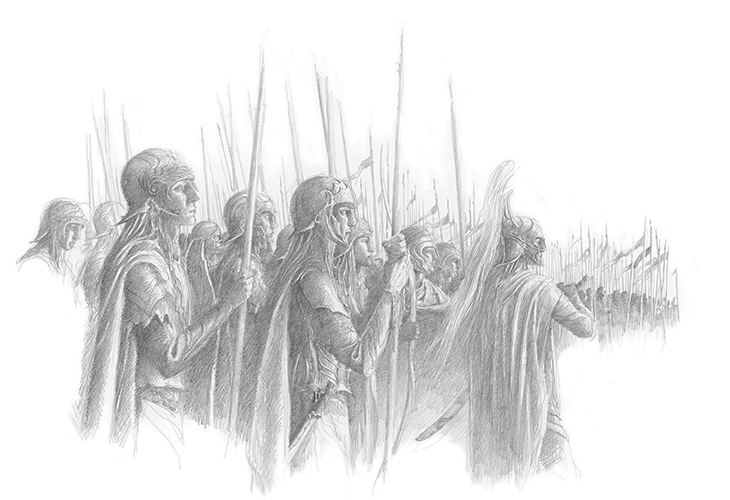

Having gathered at length all the strength that he could Maedhros appointed a day, the morning of Midsummer. On that day the trumpets of the Eldar greeted the rising of the Sun, and in the east was raised the standard of the sons of Fëanor; and in the west the standard of Fingon, King of the Noldor.

Then Fingon looked out from the walls of Eithel Sirion, and his host was arrayed in the valleys and woods upon the east of Ered Wethrin, well hid from the eyes of the Enemy; but he knew that it was very great. For there all the Noldor of Hithlum were assembled, and to them were gathered many Elves of the Falas and of Nargothrond; and he had great strength of Men. Upon the right were stationed the host of Dor-lómin and all the valour of Húrin and Huor his brother, and to them had come Haldir of Brethil, their kinsman, with many men of the woods.

Then Fingon looked east and his elven-sight saw far off a dust and the glint of steel like stars in a mist, and he knew that Maedhros had set forth; and he rejoiced. Then he looked towards Thangorodrim, and there was a dark cloud about it and a black smoke went up; and he knew that the wrath of Morgoth was kindled and that their challenge would be accepted, and a shadow of doubt fell upon his heart. But at that moment a cry went up, passing on the wind from the south from vale to vale, and Elves and Men lifted up their voices in wonder and joy. For unsummoned and unlooked-for Turgon had opened the leaguer of Gondolin, and was come with an army, ten thousand strong, with bright mail and long swords and spears like a forest. Then when Fingon heard afar the great trumpet of Turgon, the shadow passed and his heart was uplifted, and he shouted aloud: ‘Utúlie’n aurë! Aiya Eldalië ar Atanatarni, utúlie’n aurë! The day has come! Behold, people of the Eldar and Fathers of Men, the day has come!’ And all those who heard his great voice echo in the hills answered crying: ‘Auta i lómë! The night is passing!’

It was not long before the great battle was joined. For Morgoth knew much of what was done and designed by his foes and had laid his plans against the hour of their assault. Already a great force out of Angband was drawing near to Hithlum, while another and greater went to meet Maedhros to prevent the union of the powers of the kings. And those that came against Fingon were clad all in dun raiment and showed no naked steel, and thus were already far over the sands of Anfauglith before their approach became known.

Then the hearts of the Noldor grew hot, and their captains wished to assail their foes on the plain; but Fingon spoke against this.

‘Beware of the guile of Morgoth, lords!’ he said. ‘Ever his strength is more than it seems, and his purpose other than he reveals. Do not reveal your own strength, but let the enemy spend his first in assault on the hills.’ For it was the design of the kings that Maedhros should march openly over the Anfauglith with all his strength, of Elves and of Men and of Dwarves; and when he had drawn forth, as he hoped, the main armies of Morgoth in answer, then Fingon should come on from the West, and so the might of Morgoth should be taken as between hammer and anvil and be broken to pieces; and the signal for this was to be the firing of a great beacon in Dorthonion.

But the Captain of Morgoth in the west had been commanded to draw out Fingon from his hills by whatever means he could. He marched on, therefore, until the front of his battle was drawn up before the stream of Sirion, from the walls of the Barad Eithel to the Fen of Serech; and the outposts of Fingon could see the eyes of their enemies. But there was no answer to his challenge, and the taunts of his Orcs faltered as they looked upon the silent walls and the hidden threat of the hills.

Then the Captain of Morgoth sent out riders with tokens of parley, and they rode up before the very walls of the outworks of the Barad Eithel. With them they brought Gelmir son of Guilin, a lord of Nargothrond, whom they had captured in the Bragollach, and had blinded; and their heralds showed him forth crying: ‘We have many more such at home, but you must make haste if you would find them. For we shall deal with them all when we return, even so.’ And they hewed off Gelmir’s arms and legs, and left him.

By ill chance at that point in the outposts stood Gwindor son of Guilin with many folk of Nargothrond; and indeed he had marched to war with such strength as he could gather because of his grief for the taking of his brother. Now his wrath was like a flame, and he leapt forth upon horse-back, and many riders with him, and they pursued the heralds of Angband and slew them; and all the folk of Nargothrond followed after, and they drove on deep into the ranks of Angband. And seeing this the host of the Noldor was set on fire, and Fingon put on his white helm, and sounded his trumpets, and all his host leapt forth from the hills in sudden onslaught.

The light of the drawing of the swords of the Noldor was like a fire in a field of reeds; and so fell and swift was their onset that almost the designs of Morgoth went astray. Before the decoying army that he had sent west could be strengthened it was swept away and destroyed, and the banners of Fingon passed over the Anfauglith and were raised before the walls of Angband.

Ever in the forefront of that battle went Gwindor and the folk of Nargothrond, and even now they could not be restrained; and they burst through the outer gates and slew the guards within the very courts of Angband; and Morgoth trembled upon his deep throne, hearing them beat upon his doors. But Gwindor was trapped there and taken alive and his folk slain; for Fingon could not come to his aid. By many secret doors in Thangorodrim Morgoth let forth his main strength that he had held in waiting, and Fingon was beaten back with great loss from the walls of Angband.

Then in the plain of the Anfauglith, on the fourth day of the war, there began the Nirnaeth Arnoediad, all the sorrow of which no tale can contain. Of all that befell in the eastward battle: of the routing of Glaurung the Dragon by the Dwarves of Belegost; of the treachery of the Easterlings and the overthrow of the host of Maedhros and the flight of the sons of Fëanor, no more is here said. In the west the host of Fingon retreated over the sands, and there fell Haldir son of Halmir and most of the Men of Brethil. But on the fifth day as night fell, and they were still far from Ered Wethrin, the armies of Angband surrounded the army of Fingon, and they fought until day, pressed ever closer. In the morning came hope, for the horns of Turgon were heard, as he marched up with the main host of Gondolin; for Turgon had been stationed southward guarding the passes of Sirion, and he had restrained most of his folk from the rash onslaught. Now he hastened to the aid of his brother; and the Noldor of Gondolin were strong and their ranks shone like a river of steel in the sun, for the sword and harness of the least of the warriors of Turgon was worth more than the ransom of any king among Men.

Now the phalanx of the guard of the King broke through the ranks of the Orcs, and Turgon hewed his way to the side of his brother. And it is said that the meeting of Turgon with Húrin who stood beside Fingon was glad in the midst of the battle. For a while then the hosts of Angband were driven back, and Fingon again began his retreat. But having routed Maedhros in the east Morgoth had now great forces to spare, and before Fingon and Turgon could come to the shelter of the hills they were assailed by a tide of foes thrice greater than all the force that was left to them. Gothmog, high-captain of Angband, was come; and he drove a dark wedge between the Elven-hosts, surrounding King Fingon, and thrusting Turgon and Húrin aside towards the Fen of Serech. Then he turned upon Fingon. That was a grim meeting. At last Fingon stood alone with his guard dead about him, and he fought with Gothmog, until a Balrog came behind him and cast a thong of steel round him. Then Gothmog hewed him with his black axe, and a white flame sprang up from the helm of Fingon as it was cloven. Thus fell the King of the Noldor; and they beat him into the dust with their maces, and his banner, blue and silver, they trod into the mire of his blood.