Полная версия

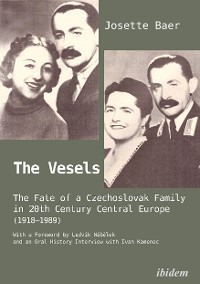

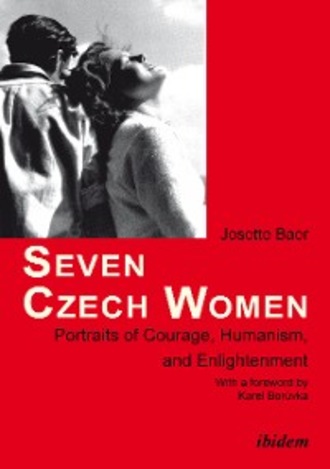

Seven Czech Women

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

Dedication

Abbreviations

Foreword

Acknowledgements

X. Introduction

X. 1 Criteria of selection

X. 2 The portraits

X. 3 The method

X. 4 A brief word on gender studies in Central Europe

I. Ema Destinn (1878–1930) – a Bohemian in New York

I. 1 The historical context

I. 2 Emmy or Ema? Destinn’s success, work for independence and decline

I.3Conclusion

II. Alice Garrigue Masaryková (1879–1966) – the First Czech feminist?

II. 1 The historical context

II. 2 Imprisoned for being a daughter

II. 3 The Czechoslovak Red Cross as the fulfilment of “small works” (drobná práce)

II. 4 Conclusion

III. Eva ‘Mimi’ Jiránková (1921–2015) – a witness of Democracy and Nazism (OHI)

IV. Milada Horáková (1901–1950) – executed for her belief in Democracy

IV. 1 Historical context

IV. 2 Milada Horáková – a democrat and feminist

IV. 3 The propaganda campaign creating the Socialist Citizen

IV. 4Conclusion

V. Věra Čáslavská (*1942) – an Olympic champion punished with silence

V. 1 The historical context

V. 2 From Olympic stardom to social isolation

V. 3 Conclusion

VI. Nataša Lišková (*1949) – a Czechoslovak citizen (OHI)

VII. Tereza Maxová (*1971) – Beauty and the care of children (OHI)

Conclusion

Chronology

Bibliography

Dedication

In memoriam Eva ‘Mimi’ Jiránková (1921–2015)

This study is dedicated to Czech women in particular and women in general, wherever they live. Two of them are particularly dear to me: Marta Neracher taught me Czech in the late 1980s and sent me off to study at the letní škola (Summer School of Bohemian Studies) at Charles University – a summer month in Prague in 1991 that would crucially determine my life as a scholar specializing in Czechoslovak history. Thanks to my knowledge of Czech, I eventually met Mimi. Every day, I miss Mimi’s optimism, straightforwardness and black humour, her happy and energetic voice. We used to talk about Czech and world politics on the phone at least once a week. When we spent time together walking in Prague, Mimi used to explain to me how that particular house or that particular corner looked in Masaryk’s Republic and how it changed during the German occupation. Her witty and enlightened comments about what was happening doma taught me a lot about Czech politics in the 20th and 21st centuries. Dearest Marta, thankfully we will still meet up for our traditional cup of tea and talk about Czech literature and our lives as scholars at the university. Dearest Mimi – we all follow.

Abbreviations

CCCentral Committee of the Communist Party

CSCECommission for Security and Cooperation in Europe

ČNBČeská Národní Banka – Czech National Bank

ČSČKČeskoslovenský Červený Kříž – Czechoslovak Red Cross

ČSNSČeskoslovenská Strana Národně Socialistická – Czechoslovak National Socialist Party

ČSSČeskoslovenská Strana Socialistická – Czechoslovak Socialist Party

ČSTVČeskoslovenský Svaz Tělesné Výchovy a Sportu – Czechoslovak Association for Physical Education and Sport

FTVSFakulta Telesné Výchovy a Sportu – Faculty of Physical Education and Sport

HZDSHnutie Za Demokratické Slovensko – Movement For a Democratic Slovakia

KSČKommunistická Strana Československá – Czechoslovak Communist Party

KSSKommunistická Strana Slovenska – Slovak Communist Party

MNVMístní národní výbor – local branch of the Czechoslovak National Council

NAMNon-Alignment Movement

NBČSNárodní Banka Československá – Czechoslovak National Bank

ODSObčanská Demokratická Strana – Civic Democratic Party

OFObčanské Forum – Civic Forum

OSSOffice of Strategic Services

OSCEOrganization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

SAVSlovenská Akademie Vied – Slovak Academy of Sciences

SBČSStátní Banky Československé – Czechoslovak state banks

SNKSlovenská Národná Knižnica, Martin – The Slovak National Library, Martin, Slovak Republic

SNRSlovenská Národná Ráda – Slovak National Council

SNPSlovenské Národné Povstanie – Slovak National Uprising

StBStátní Bezpečnost – State Security Service

ÚV KSČÚstřední výbor Kommunistické Strany Československá – Central Committee of the Czechoslovak Communist Party

VPNVerejnosť Proti Násilie – Society Against Violence

ŽNRŽenská Národní Ráda – Czechoslovak National Women’s Council

Foreword

Josette Baer’s book is a very interesting undertaking, which offers an insight into the volatile history of the 20th century, through to the present day, in the Czech lands and, in a wider context, also in Europe and the world, through the fates and activities of seven women. The author set herself the difficult task of presenting women of various professions, who originated from different backgrounds and distinguished themselves also in their significance in the international context. What they all have in common, though, are their humanism and attempts to promote these values. Also, the women portrayed do not let themselves get carried away by the historical events, but try to influence them, each one in her own particular way.

Josette Baer is an experienced author, her book is most readable and informative. I am no friend of lengthy forewords and explicatory comments. Readers should form their own opinions. In any case, I recommend reading this book carefully and I thank the author for her admirable work. Reading it is very inspiring, offering a deep insight into the subject matter.

Karel Borůvka

Ambassador of the Czech Republic to Switzerland

Bern, Switzerland, July 2015

Acknowledgements

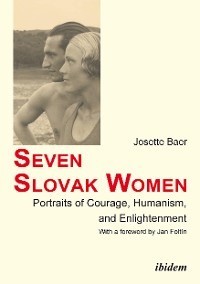

This volume is the second of a two volume project of Czech and Slovak History seen through the eyes of women. The first volume Seven Slovak Women was published in April 2015.

This volume Seven Czech Women is a study in its own right, focussing on Czech women’s life histories. Owing to the peculiar history of the Czech lands before and after the Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1992), the seven portraits explain the specific political circumstances Czech women were facing from the late 19th century to the present day. Seven Czech Women and Seven Slovak Women provide the reader with a comprehensive picture of women’s lives in Central Europe; the volumes can explain, to some extent, the disparate development and political and cultural identity of Czech and Slovak women.

My thanks. I am greatly indebted to my colleagues and friends for their interest in my research and willingness to discuss specific issues with me. My thanks, in alphabetical order, go to Zdeněk V. David, Markéta Doležalová, Blanka Hajnová, Kristina Larischová, Radka Handlová, Vladimír Handl, Thomas Hardmeier, Adis Merdzanovic, Slavomír Michálek, Miroslav Michela, Daniel E. Miller, Marta Neracher, Marie Neudorflová, Libora Oates-Indruchová, Francis D. Raška, Nikola Todorović and Martin Vadas. The ladies at the Prague National Library Clementinum were very professional and went to great lengths to help me with finding the source material crucial for this volume.

Karel Borůvka, the Ambassador of the Czech Republic to Switzerland, supported this book from the start, and I am honoured that he agreed to write the preface. Valerie Lange at ibidem publishers in Stuttgart is an exceptionally patient, effective and supportive editor. Peter Thomas Hill proofread the manuscript, perennially soldiering on with the demanding task of teaching me English that is up to his own high standards.

I would like to express my gratitude and respect to the ladies who agreed to participate in my oral history interviews, which, to some, meant going back in history to remember painful events. Nataša Lišková, Tereza Maxová, and Terezie Sverdlínová, your esprit, commitment, modesty, beauty, honesty and intellect are inspiring – you are in a league of your own. Sadly, Eva ‘Mimi’ Jiránková, my great friend, can no more witness the publication of this volume. Mimi passed away peacefully on 26 April 2015 at the age of 93 at her Devon home, surrounded by her loving family.

The errors and shortcomings in this volume are my own.

Josette Baer

Zurich, Switzerland, and Prague, Czech Republic, August 2015

X. Introduction

This book[1] is the second volume of my project Slovak and Czech History from a female perspective. I became interested in the history of Slovak and Czech women because of the superb study my friend and colleague Gabriela Dudeková published in 2011.[2] As a political scientist focussing on the history of political thought in Slavic Central and Eastern Europe, and a careful student of Czech, Czechoslovak and Slovak political history, I admired Gabriela’s study; in a tour de force reaching from the 19th to the 21st centuries, she and her fellow authors analysed the political situation of Austrian, Czech, Hungarian and Slovak women, providing copious historical analysis based on archive material in four languages.

Neither the first[3] nor this second volume is a contribution to theories of gender or nationalism studies. I would like to present to the Western reader the history of the Czech lands seen through the eyes of seven women who lived through one hundred and fifty years of the often cruel political waves so characteristic of Central European history. If an interest in women’s lives and a distinct curiosity about how women fared in history is considered a feminist approach – then this volume has a feminist focus and should be considered a modest contribution to feminist historiography with a focus on Czech women.

X. 1 Criteria of selection

I selected the seven women on subjective grounds since, in my opinion, they represent the spirit and reality of seven distinct historical eras of Czech and Czechoslovak history. My three criteria for selection are: all of them have a Czech cultural and political identity; second, their visibility in the Czech, Czechoslovak and international public eye; and third, their physical presence in the Czech lands.

Compared with the volume on Slovak women, I have made three exceptions for this book with respect to visibility and physical presence. First, although she emigrated in 1948 after the Communist coup d’état, Eva ‘Mimi’ Jiránková’s story (chapter III) is a lively account of the liberties Czech women enjoyed in the First Republic (1918–1938) and how their lives changed with the beginning of the German occupation in March 1939. She was most probably the only woman in history whose husband was arrested by the Gestapo on her wedding night. Second, Nataša Lišková (chapter VI) is what one would call an ordinary citizen, that is, without ties to the Communist Party or influential relatives; she is not a celebrity. Yet, her personal account of the normalization provides us with a vivid picture how Czech women experienced the liberties of the Prague Spring and the post-68 tightening of the political screw dictated by Moscow. Bringing up children in the harsh political and economic realities of the Husák[4] regime was a daily ordeal. Third, as a world-famous top model, Tereza Maxová is highly visible in the Czech and international public sphere; she is not a resident of the Czech Republic, but frequently travels to Prague to support the activities of her foundation.

Thus, given that the Western reader is much more familiar with the names of famous Czech (-born) women such as Madeleine Albright, Olga Havlová, Marta Kubišová, Martina Navratilova, Božena Němcová,[5] Petra Kvitová and Ivana Trump, I took the liberty to make the exceptions mentioned above: Mrs Jiránková emigrated and she is not a celebrity. Mrs Lišková stayed in Czechoslovakia, and she is not a celebrity either, and Mrs Maxová is a celebrity who lives abroad.

Each woman can be seen as a symbol of her times representing the spirit and reality of the historical era in which she lives and acts. All seven women share their belief in women’s equality with men, political liberty and participation in a rule-of-law state and fraternity. They share the idea that caring for others in the sense of res publica, that which is common to all, is the social glue that keeps state, nation and government together. They share also a crucially important legacy of the Enlightenment: tolerance. Only tolerance as the civilized lack of interest in what others, my neighbour, my friend or my colleague, believes in allows for pluralism, which is the principal element of a democratic civil society.

My selection is not representative – and I don’t claim that it is. Furthermore, it is far from my intention to belittle or ignore the effort millions of Czech women made in the Austrian monarchy, during the two world wars, under the German protectorate and Communism to bring up their families. On top of scarce resources, they had to deal with an immense bureaucracy and a patronizing state that treated the citizens as children, depriving them of the most basic civil rights, such as the right to leave one’s country. After 1989, citizens had to deal with the harsh transformation of the economic system; Capitalism, with its often inhuman face, did not acknowledge a right to work.

It is far from my intention to make a moral judgement about those who emigrated; nobody who has not experienced daily life in a non-democratic political system, be it a monarchy run by the aristocracy and the clergy or a workers’ paradise governed by the Communist Party, should be judgemental of those who leave in the hope of finding a better life for themselves and their families. My focus is on the seven Czech women who can teach us a lot about courage and commitment; they voice, through their activities, what millions of unknown Czech women were and are concerned with, sharing with them the often brutal experience of Czech and Czechoslovak politics.

Before I present the portraits, a brief note about the historical epochs dealt with in this volume: my principal aim was to avoid repetition. My selection of portraits should thus be understood as a deliberate choice designed to throw light on specific political events and realities that affected each nation and its history in their own particular way. Therefore, I do not deal with the Munich Agreement of 1938, Hitler’s dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1939 and WWII in this volume, since I have dedicated chapter III of the Slovak volume to this period. Chapter IV of this volume is dedicated to the Communist Party’s assumption of power in February 1948 and the early years of Czechoslovak Stalinism, because I have not dealt with these years in the Slovak volume. The political liberalization starting in the 1960s and culminating in January 1968 with Alexander Dubček’s (1921–1992) election to First Secretary of the KSČ, the Prague Spring, the invasion and the normalization are presented extensively in chapter IV of the Slovak volume. Yet, the normalization affected the Czechs in a different way than the Slovaks; therefore, I present a brief summary of the normalization in the Czech part in chapter V, focussing on two specific aspects of those years.

The years following the separation of Czechoslovakia in 1993 are not dealt with in this volume, since I presented them in my oral history interviews with the Czechoslovak diplomat and Slovak politician Magdaléna Vášáryová (*1948) and former Slovak Prime Minister Iveta Radičová (*1957).[6] The interviews introduce the reader to the difficult years from 1994 to 1998 when Vladimír Mečiar (*1942) was Prime Minister of the young Slovak Republic. By contrast, there was no threat of a relapse into communist-style authoritarianism in the young Czech Republic. Western political orientation and the democratic and market-orientated spirit of the Czech government with the late Václav Havel (1936–2011) elected Czech President in 1993 dominated the years after 1993.

Naturally, the seven Czech women I chose are of the same singular importance for the Czech lands as their Slovak counterparts were for their nation. The two volumes are separate entities in their own right and complement each other with respect to the historical contexts presented in both volumes; the two together should be perceived as companion books, providing the reader with a comprehensive picture of women’s lives in the Czech lands and Slovakia, stressing the distinct political circumstances Slovak and Czech women had to cope with.

X. 2 The portraits

In the last decades of the 19th century, Ema Destinn (1878–1930) was a famous opera singer whose international career peaked when she got a contract with the New York Metropolitan Opera. Destinn was a Czech patriot and supported the movement for an independent Czechoslovakia.

Alice Garrigue Masaryková (1879–1966), the future president’s daughter, studied history and philosophy at Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague and worked as teacher at a high school for girls. She was the chairwoman of the Czechoslovak Red Cross and died in US exile.

Eva ‘Mimi’ Jiránková (1921–2015) was a witness to the democracy of the First Republic and the protectorate under Nazi occupation. She was born in Prague and fled Czechoslovakia with her husband Miloš and their little daughter Martina in 1948. After she retired from her work as fashion consultant for Liberty’s in Great Britain, Mimi and Miloš moved to Devon. Until her death in April 2015, Mimi regularly visited her native Prague.

Milada Horáková (1901–1950), a lawyer and politician, member of the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party (ČSNS) and close to President Edvard Beneš (1884–1948), was accused in the Stalinist show trial of 1950 as a traitor. The Communist government executed her. During WWII she had been active in the Czech resistance movement.

Věra Čáslavská (*1942), a gymnast, became known to the world when she won Olympic gold in Mexico City in 1968, just two months after Warsaw Pact troops had occupied her country. She is the most successful female athlete in Czech history.

Nataša Lišková (*1948) was born in Prague and brought up her children in the difficult years of the normalization. Nataša is a retired freelance journalist and spends her time with her grandchildren in the countryside.

Tereza Maxová (*1971) is a world-famous top model and one of the first Czechoslovaks who conquered the world of fashion and beauty in the early 1990s. She is the founder of the Tereza Maxová Foundation for children that changed Czech society’s perception of neglected and homeless children. Her foundation is a crucially important contribution to Czech civil society, the self-organization of citizens.

X. 3 The method

In methodological terms this volume is eclectic. Chapters I, II, IV and V are in the form of essay; I describe the four women’s lives based on source material in Czech, using traditional historical analysis. A short introduction at the beginning of each of the essay chapters introduces the reader to the historical context.

In chapters III, VI and VII I use the method of the oral history interview (OHI). This method has a considerable advantage for the author and the reader alike – it is history rendered vibrant through the individual expression, description of events and memory of a person involved in the historical context subject to investigation.

The main research questions of this volume are: how did and do women deal with political, social and economic issues? How did the rights of Czech women change from the 19th to the 21st centuries and what are they concerned with today?

From the last decades of the 19th century to the first decade of the 21st, Czech women lived through seven political regimes:

1 The Austro-Hungarian empire (1867–1918);

2 Czechoslovakia (ČSR, the First Republic, 1918–1938);

3 The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (1939–1945);

4 Post-war Czechoslovakia (ČSR, the Second Republic, 1945–1948);

5 Communist Czechoslovakia (ČSR, 1948–1989, after the federation of 1970 referred to as ČSSR);

6 The democratic Czechoslovak Federation (ČSFR, 1990–1992);

7 The Czech Republic (1993–) after the Velvet Divorce.[7]

Of these political regimes, the First Republic, post-war Czechoslovakia from 1945 to 1948 governed by the National Front, the Czechoslovak government established after the Velvet Revolution (Sametová revoluce) of 1989 and the Czech Republic after the Velvet Divorce (Sametový rozchod) of 1993 were legitimate in democratic terms.

Czech Prime Minister Václav Klaus (*1941) and Slovak Premier Vladimír Mečiar could not find common ground to set a course for economic privatization. In the summer of 1992, they agreed to divide the state, popularly referred to as the Velvet Divorce, in analogy to the Velvet Revolution that began on 17 November 1989.[8] In legal terms, the agreement to separate was a violation of the Czechoslovak Federal Constitution that required a plebiscite.[9]

On 1 January 1993, the Czech and Slovak Republics came into being, internationally recognized as sovereign states. The international community was occupied with the war in former Yugoslavia and the political situation in Russia; hence the peaceful, apparently democratic and negotiated separation was no burning issue. The Czech Republic achieved NATO membership in 1999 and became a member of the EU in 2004. The citizens of the small Central European state experienced the rule of the Habsburg dynasty, two world wars, the First Republic, German occupation, Communism and, eventually, the post-1989 harshness of the economic transformation from a planned central economy to a free market economy with the concomitant economic and social problems.

X. 4 A brief word on gender studies in Central Europe

Western historians have been working on gender issues for decades; little is known, however, about the history of women in Central Europe. In the 19th century, Czech women found themselves in a difficult situation. On the one hand, they were eager to engage in what we call gender issues today, for example, to found educational institutions for girls. On the other, they shared men’s views that the Czech national movement opposing Austrian rule required the nation’s united resistance.

Female emancipation in the Western understanding of the freedom to choose how to spend one’s life would have meant fighting a battle on two fronts: first, against the domination of men, and second, against political oppression. Of crucial importance to women in the Habsburg monarchy in the 19th century was the opening up of the public sphere, contextualizing women’s public appearance in the national and cultural spolky[10] (associations, clubs) such as choirs and reading circles. The main activities of women were traditional female activities: social care, charity, literature, and the teaching of cooking and sewing. The education of girls was not a burning issue since a labour market for women did not yet exist, save, of course, for the lowest class, the servants. Farmers’ girls from the countryside sought to improve their families’ income with employment in the city. Few women of social standing engaged in the international women’s movement; the majority still adhered to the conservative view that women represented the values of faith, modesty, industriousness and, above all, passivity and obedience to men.