полная версия

полная версияThe Florist

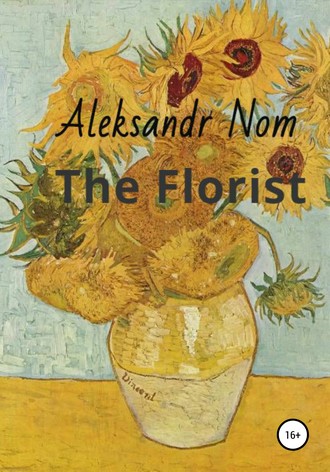

Image: Vincent Van Gogh – The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202. Public domain; https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=151972

A hangover-looking man in crumpled clothes was wandering around a huge flea market. Without much zeal, he was browsing, on the lookout for paints and brushes which sometimes were sold on the cheap here by failed artists same as himself.

Also, a part of his mind was wondering whether he should better spend what money he had left on some poison pills or a gun, to put an end to it all. He would never hang himself or jump from a height onto pavement – the body looking unaesthetic in such cases, – but a poison or a bullet could do the job just nicely.

His eye was caught by an odd composition – aside from the other vendors, a respectable-looking individual was sitting gravely on a folding chair. A suit of expensive fabric, hand-made shoes, a Swiss watch and a tie whose price would make the artist’s monthly living… Towering behind his back, was a broad-shouldered guard.

What could this alpha male be doing in a flea market where rows of pensioners were displaying time-darkened silver cutlery and chipped faience figurines while drunkard astronauts were trying to palm off their moonstones which were no more exciting than rocks from the nearby quarry?

The artist approached.

In front of the suited individual stood a wooden box used as a table, with a potted flower on it. Not really beautiful, the flower had a catching quality to it. On taking a closer look, the artist realized what it was: the flower was the spitting image of the Sunflowers by his beloved Van Gogh.

“What’s it called?”

“There’s no name. If you take it, you can give it a name to your liking.”

“I would call it Van Gogh.”

“It’s your business.”

“How much does it cost?”

“Nothing. There’s no price. But, mind you, the bastard is not easy to keep. What are you, anyway?”

“An artist.”

“You look more like a bum.”

“I’ve hit a bad patch,” admitted the artist.

“I see,” the man responded indifferently.

“I’ve never seen anything like this. Where did you get it?”

“Why, in this very market, a year ago. At that time I was… No matter, forget it. So, you take it or what?” The man glanced at his Rolex. “Make up your mind, man, I don’t have all day.”

“I take it,” the artist found himself saying.

“Then this is for you.”

The man thrusted into the artist’s hand a shabby brochure titled, ‘Flower Care Guide’.

“And here’s another thing,” the man said, rising. “If you decide to get rid of it, don’t just throw it away but come here and give it to someone.”

The care of Van Gogh was indeed a demanding job. Firstly, the flower did not tolerate dust. The artist’s studio, where he slept, ate, drank, and occasionally did some painting, was in a dire state of neglect. Now he had to throw out trash and do a thorough wet cleaning.

The room had to be constantly aired, but without overcooling.

And – the light. Van Gogh required a lot of light, so all the windows had to be washed.

In the bright light, the painter saw anew his creations of the recent years. He felt dismay, struck by his own professional and artistic degradation.

Luckily, he had no time to grieve over that, his mind full of concerns about Van Gogh.

The flower could be watered with pure spring water only. The guide contained a warning that there was a lot of counterfeits on sale, and instructions on how to test the quality of the product. Finally, with difficulty, the painter found genuine spring water. Once he started using it on Van Gogh, the flower revived noticeably, its color getting brighter. The painter took a sip of that water himself, and he liked it. From then on, he drank it constantly.

The leaves required spraying and the soil required the application of fertilizers strictly according to the list – phosphate, nitrate, potash, and a dozen other chemicals.

But the main problem was the mysterious gravicola. The brochure said, “Once a week, introduce 40 drops of gravicola to the soil at the base of the stalk.”

There was no indication as to what in the world that gravicola was, and where it could be found. The web florist sites returned no answers.

After a week, the gravicola-deprived Van Gogh began drooping and wilting, even shedding its leaves.

The artist went to the market and started harassing the old ladies who were selling cactuses and geraniums. The old ladies shook their heads and shrugged in bewilderment.

“Hey, wait! Did you say ‘gravicola?’”

Beside another old lady, an unshaven guy in a jacket with a NASA chevron was sitting. An astronaut.

When engines were invented that enabled flying to faraway planets, the world was swept with an astronautics craze. However, it soon became apparent that space flights, while burning huge budgets, did not bring any substantial gain. The projects of exploring deep space were cut down. Thousands of jobless astronauts had a hard time re-adapting to Earth – bitter and depressed, they could be seen everywhere including flea markets where they were bargaining off their souvenirs to make a little money for booze.

“Did you say ‘gravicola’? Why do you want it?”

“It’s for my flower. Do you have it?”

As it turned out, ‘gravicola” was a slang word which in the language of astronauts referred to some product of high chemistry. The substance helped astronauts cope with the transition from a high gravitation to the zero space one, and back.

“I’ve never heard of gravicola being used on flowers. On the other hand… A friend of mine uses it on his cat – he says it’s good for fleas.”

The astronaut scratched his head.

“I guess, I have a bottle of it stacked somewhere. I got no use for it, seeing that I won’t be doing any more flights.”

The next day, the artist received a bottle of gravicola from the astronaut and hastened back to his studio.

The very first drops produced a magical effect – Van Gogh started spreading out immediately. After forty drops, it was a large, robust plant.

He did not do portraits – maybe exactly because he was a natural physiognomist. It took him just one glance to see through a person. He saw vulgarity, selfishness, greed, envy, and malice – everything that people were carrying around, sometimes being honestly unaware of it.

There was one exception. They went to an artistic school together, and she was perfection itself.

She hated posing. “I’m bored,” she would laugh. “Let’s go for a walk. Let’s go to the cinema. Let’s go somewhere!” That was how she was captured in the portrait – laughing, sitting momentarily, as a bird on a branch, ready to fly off the next second in order to be free and rejoice in life.

It never worked out for them. His youthful belief was that, to lay claim to such a girl, one had to be a successful, wealthy man, which he was far from being.

After they graduated from their school, she became a textile designer. The textiles she created were free and joyous like herself. Then she got married, had children and went away to another country. He has not heard from her since. As a remembrance, he had her portrait which was buried in a corner of his studio, blocked up by other canvasses.

Now necessity forced him to turn again to the portrait genre, so to speak. Try as he might to keep that prospect away, one sunny day he came out onto the boulevard with an easel and camp stool, in order to make impromptu portraits of idle passers-by. That was the bottom, nothing could be worse for an artist. He would have preferred a bullet or a poison, but he was not alone now – he had to take care of Van Gogh.

Surprisingly, he did well in the boulevard-portrait business. He knew that people did not want the truth about themselves – everyone wanted flattery. And he flattered them: he made fat into imposing, scrawny into slender, ugly into special and interesting, and nondescript into mysterious and full of latent content. It was easy with women – they all wanted to be prettier than they actually were, and it only took him a few strokes to fulfill their dreams while preserving a good likeness.

People stood in line for him to depict them. He earned a living for himself and for Van Gogh.

The other boulevard artists were envious and once they beset him demanding that he bugger off from their territory. The artists were dispersed by the local cops who made it very clear to the creative lot whose territory it really was. The law enforcers collected tribute from everyone who earned money on the boulevard and they took the job of maintaining order quite seriously.

That was hell. Every day, the artist wondered how he had lasted another day. His dislike of human faces grew into real hatred. He hated people and he hated himself for what he was forced to be doing.

One day, the bubble of that hatred burst.

Generally, he tolerated children although some specimens were real awful. That one disgusted him at once – not because he was fat as his gigantic dad who was holding tenderly his heir’s hand, but because at such young age already, almost all the human vices were imprinted on the boy’s face.

The boy was eating an ice cream, picking his nose and driving a dog on a leash, all at the same time. The dog immediately started barking at the artist.

“Lose the ice cream,” asked the artist.

“Catch me!” the little monster cried and stuck out his tongue.

Encouraged by his cry, the dog burst into hysterical barking.

The artist did not have the energy to argue. He depicted the object just as he was – with ice cream in his mouth and his index finger immersed deeply in his nostril.

On seeing this, the father raised his voice:

“What do you think you’re doing? Mocking us? Do it properly!”

The artist picked a brush and added a few strokes to remove the ice cream and the finger.

Now the boy in the portrait was not a monster but just a little moron.

The father liked it.

“See, you can do it if you make the effort.”

The dog decided to take a more active part in the action. It ran up, tugged at the artist’s trousers, and then let out a yellow trickle on his leg.

“Ha! Watch Archie piss on the painter!” the boy cried, in raptures.

Then he started tugging his father’s arm.

“Dad, tell him to draw Archie!”

“Go ahead, do it,” the father ordered. “All right, I’ll give you half the price for the dog. I’m not some kind of cheapskate.”

“I don’t do animals,” snapped the painter, hiding his leg.

At once the boy got all worked up and started shouting and stamping his feet.

“You bastard! How dare you bully a kid?” The man approached threateningly. “I say draw it!”

“Go fuck yourself,” said the artist, folding his easel.

He did not even feel the blow.

When he came to, the father and son were gone. Collecting his stuff from the ground, the artist discovered that the loving parent had not forgotten to take the drawing with him while forgetting to pay.

He had had drinking bouts before, but those did not last long, just a couple of days. This time, he went into an alcoholic tail-spin in earnest. He made preparations – brought a large case of bottles to his studio – and started drinking in an orderly way.

For a long time, he did not see anything in his alcoholic trance – he was just hovering around in a dark, empty expanse.

By the end of the week, hallucinations came. His hallucinations were not about some banal imps but about paintings. Floating before him in a succession, were pictures that he had never painted.

From his youth, he was allured to urban landscape, but that passion was killed by a total lack of demand. Connoisseurs looked down on the genre considering it to be too conventional and bourgeois, while simpler people did not understand why they should pay for what could be captured on a mobile phone just as well. Now he saw his unpainted cityscapes in every detail.

Then the succession of landscapes stopped and he found himself within one of them. Only it was not his motif – a narrow, cobblestone street with low-rise houses standing wall-to-wall on both sides looked like an old town in a French province.

It was late evening, and the sky above was full of sparkling stars. The brightly-lit terrace by a cheap café was empty except for a single male figure at a table.

He approached. The man’s head was bandaged, the bandage keeping in place a cotton tampon applied to the ear. A large nose, high cheekbones, light eyes, red stubble. On the table was a cardboard on which the man was busily drawing something.

“Maestro Van Gogh!”

The sitting man did not turn his head.

“Maestro, it’s a great honor, and all that… Your paintings cost many millions nowadays. To think that in your time, you could lack money for a dinner! Tell me, how did you manage to paint? Over two thousand works in ten years!”

The man at the table was still absorbed in his drawing.

“I know what you will say – that one must serve his talent disregarding anything material. Everyone says so, but not everyone can live up to it. Good for you, you’re a genius, you got it all covered. Me, I’m no genius…”

The stars above dimmed, the contours of the houses blurred, and the figure by the table started getting transparent. Yet, before vanishing completely, the bandaged genius held out something, without turning round, to his uninvited visitor. It was a brush.

The artist woke from his alcoholic oblivion. What he had in his hand was not a brush but a branch from his flower. When and why he had broken it off, he had no idea.

He was dripping with sweat and shivering. By a desperate effort, he sat up on the sofa and put his feet down on the floor. He could not walk, his legs refusing to hold him up, so he had to crawl on all fours all the way to the window. Here, he clung on the big bottle of spring water meant for the flower and chugged at least a liter of it. It felt a little better.

Only after that his vision focused on rusty patches which were leaping to his eyes.

The flower was dying. All covered in an awful blight, it had already ceased fighting for itself.

The guide was a bitch to find, but finally it cropped up under the sofa. The painter’s fingers would not obey him, and the letters were dancing before his eyes. It took him a while to find what he was looking for: “In case of blight damage, the Flower can be cured only by classical music.” An instruction printed in bold type said that only analogue records, on vinyl, answered the purpose.

Vinyl records were rare, cost a lot, and could only be found in music lovers’ collections. The painter was not into music but he possessed an Ella Fitzgerald vinyl record left to him by his melomaniac grandfather.

He retrieved the record from the top of the bookshelf. He even dug up an old record player which, miraculously, had never been thrown out and rested peacefully in the depth of the closet.

Issuing crackling sounds, the record filled the studio with a base, penetrating, black woman’s voice. It was neither Bach or Mozart, but it was classical music of sorts.

And it had its effect, the flower started coming back to life visibly.

Then the process reversed – the flower drooped, the rusty patches started growing again. Probably, the flower required some other kind of music, or it did not do to play the same record all the time.

For two days, the artist sat motionless in a chair, listening to Ella Fitzgerald and gazing at the dying flower.

On the third day, he unearthed the gallery owner’s address and set off to visit him.

Once the gallerist started his business in a suburb, in the basement of an abandoned building which was always crowded with penniless Bohemia. Now he had a spacious exhibition hall in the center of the city, where all the walls were hung with good paintings.

In the empty hall, there were smells of coffee and tobacco – the gallerist whose hair had turned noble grey was sitting at an antique table by the window, puffing at a cigar and contemplating the street bustle.

“You don’t seem to have a lot of visitors,” remarked the artist by way of greeting.

“I don’t need a lot,” responded the gallerist. He exuded Buddhist calm rarely found among the people associated with art.

“Do you recognize me?”

“Of course I do. I never forget either people or paintings. Do you bring something?”

The artist started showing the paintings he brought. The gallerist turned them over without any interest.

“You don’t like them?” asked the artist.

The gallerist sighed.

“Let me be honest with you. You painted all this in the hope of making money. You despised those who would buy it and you despised yourself for doing this. What is there to like in this?”

“You’re not taking anything? I’m not asking much.”

“No. Sorry,” replied the gallerist in a tone that brooked no bargaining.

The artist lingered, hesitating to do what was left for him to do.

“Then look at this,” he said, tearing off the wrapping paper from the last canvass.

The gallerist put the painting on an easel, turned it towards the window, and began examining it in silence.

The girl in the portrait seemed even younger – maybe because the two men who were looking at it had grown noticeably older.

The pause dragged on.

“I’ve already shown it to you once,” said the artist, unable to bear the silence. “You wanted to buy it.”

“Yes, I remember,” responded the gallerist. “I wanted to buy it, but you wouldn’t sell… Today, I’m not buying it.”

“Why? You don’t like it any longer?”

“I do. I like it very much, but… You see, it is too personal and obviously dear to you. Your bringing it to me means that you are desperate, and I would be a vulture to take advantage. That wouldn’t stop me when I was younger but with years, I’ve come to see certain things differently.”

He returned the painting to the artist who started packing his canvases, preparing to go.

“What’s that in the folder?” asked the gallerist.

“It’s nothing, just a sketch…”

“Let’s see it.”

The painter extracted a cardboard. It was a drawing of the flower which he meant to throw in to speed up the sale of his paintings.

The gallerist put the cardboard on the easel.

“Strange,” he said. “It seems familiar.”

“It looks like Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, but it’s not an imitation.”

“My dear fellow, I’m familiar with Van Gogh, believe me,” the gallerist said with reproach. “And I see that it’s not an imitation. Are you selling?”

Without bargaining, the gallerist bought the drawing for a price that struck the painter as enormous.

“Tell me, have you painted something for yourself? I mean, besides that portrait,” asked the gallerist while he was helping the artist pack up his works.

“I tried my hand in urban landscape but I gave it up.”

“I’d like to see that stuff of yours.”

“But there is no demand for that!”

“Demand is my concern. Bring me your landscapes.”

The artist brought his old cityscapes, and the gallerist exhibited them for sale. Apparently, he really knew his job and had a good clientele, as in a couple of weeks all the paintings had been sold.

The painter got back to work and started receiving orders. After a while, he already gained some reputation as the author of “a fresh perspective on urban landscape.”

A successful, fashionable artist cannot be without a woman, and a woman materialized.

She assaulted him at some exhibition, pushing aside a couple of less active contenders.

“You are so talented! I’ve been so looking forward to making your acquaintance!”

Unaccustomed to attention, the painter could not withstand the onrush.

Having settled in the studio, the woman began putting it to rights in her own way, and of course, she could not overlook the flower.

“What’s that?”

“It is Van Gogh.”

“What Van Gogh?”

“Well… It’s a long story,” the artist dodged explanations.

“I don’t like it. It has neither a good look or a smell.”

With the woman about, the artist stopped drinking, started having regular meals, getting up in the morning and working every day.

One day Van Gogh blossomed – shot up a thin pedicle with three petals on it.

The woman plucked the pedicle and, standing before the mirror, tried to fix it into her hair. She did not like the result, and the petals went into the garbage bin.

“By the way, when are you going to paint my portrait?”

“Not now, darling. You know what a load of work I have.”

Then a little fruit looking like a quince appeared where the petals used to be.

The painter was not fast enough to stop her – she plucked the fruit, saying:

“There’s got to be some use for this plant!”

She took a bit and grimaced:

“Sour!”

Soon she announced that she was pregnant.

As many women that are in the family way, she became irritable. The flower was the first to fall victim to her bad mood.

“Take away that disgusting weed!”

“Is it any trouble?”

“It is to me. It’s stink gives me headache.”

“You said it did not have a smell.”

“Don’t argue with me! You know very well that I can’t be stressed, it’s bad for the baby.”

The artist spent a whole day in the market sitting on a camp-chair, with Van Gogh beside him.

To pass the time, he drew momentary portraits of the passers-by in his notebook. Now that he did not have to do it for a living, his hatred of human faces had subsided. After all, people were not all that bad, most were just miserable and deserved sympathy.

“What’s this flower called?”

Before him stood an intellectual-looking man wearing a goatee and a shabby coat.

“It doesn’t have a name. If you take it, you can name it yourself.”

“I would call it Hamlet. There is something of the Shakespearean hero about it – certain meditativeness, questions without answers.”

“Could be,” concurred the artist. “What are you, anyway?”

“I am a writer,” announced proudly the man in a shabby coat. Then, seeing skepticism in the artist’s eyes, he added hastily: “I’m just finishing my big novel.”

“Well, that happens,” the painter replied sympathetically. “So, do you take it?”

“What does it cost?”

“Nothing. Mind you though, it’s not easy to keep.”

The immigrant from a planet of intelligent plants was an ardent florist. Stranded on Earth, he accepted his new home wholeheartedly. The planet abounded with flowers of the species Homo Sapiens of which many were beautiful but needed urgent care.

The immigrant had already forgotten his birth name – he liked the names that earthlings invented for him. “Van Gogh” – what a beautiful name that was! “Hamlet” seemed to be no worse, although the human flower that gave him that name was in a serious state of neglect.

The Florist had a lot of work in store.

––

Contact the author: Alexander.Sharakshane@yandex.ru