Полная версия

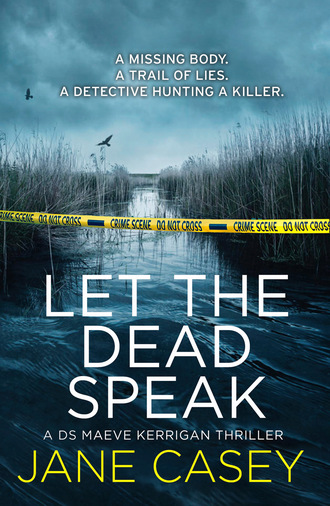

JANE CASEY

Let the Dead Speak

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Jane Casey 2017

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Silas Manhood and Shutterstock.com

Jane Casey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008149017

Ebook Edition © March 2017 ISBN: 9780008149000

Version: 2019-11-27

Dedication

For Ariella Feiner, with love and thanks.

For the good that I would I do not: but the evil which I would not, that I do.

Romans 7:19

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Keep Reading

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Jane Casey

About the Publisher

1

It had been raining for fifty-six hours when Chloe Emery came home. The forecast had said to expect a heatwave; it wasn’t supposed to be raining.

And Chloe wasn’t supposed to be home.

She came out of the station and stopped, shifting her big black bag from one shoulder to the other. The rain poured off the awning, splashing onto the pavement in front of her. It coursed into the gutters where filthy water was already swirling, dark and gritty, freighted with rubbish and twigs and dead leaves. Chloe’s T-shirt clung to her back and her stomach. She twitched the material away from her skin, self-conscious about the swell of her breasts. She hadn’t ever really thought about them until her stepmother had mentioned them.

‘Big girl like you, you need a better bra. Better support. You can’t blame men for looking, you know.’ A thin, spiteful smile. ‘You might as well enjoy it, though. They’ll be down to your knees in no time and no one will care then.’

It had taken Chloe a long time to understand what she meant, which had annoyed Belinda. She still didn’t know why Belinda was angry with her about her body, or people looking at her. A wave of unease passed over Chloe, remembering – the familiar nausea of not knowing things that other people took for granted. It wasn’t her fault; she did try.

There was no point in waiting for the rain to stop. Chloe bent her head and trudged away from the station. Her clothes and hair were saturated within a couple of minutes, her jeans cold and heavy, dragging against her skin. Every raindrop felt like a finger tapping on her head, her shoulders, her back. Her shoulder was burning where the bag strap rubbed it. There were no other pedestrians, except for a mother pushing a buggy on the opposite pavement, striding fast, the hood on her sensible anorak pulled down low over her face. Who would be out for a walk on a wet Sunday afternoon if they didn’t have to be? Not Chloe, not feeling the way she did, sick and tired and still a bit sore. But there was no one to meet her at the station. No one knew she was there.

A car engine hummed on the street behind her and she didn’t think anything of it, even when it got louder and closer. It wasn’t until the car pulled in ahead of her with a jerk of the brakes that she noticed it in any detail. The driver was leaning forward to peer into the rear-view mirror, adjusting it so she could see his eyes staring into hers. The fear came first, a thud that shook her chest as if someone had kicked her. Then recognition: it wasn’t a stranger watching her walk towards him. It was a neighbour. More than a neighbour: it was Mr Norris, who lived across the road from her, who always smiled and asked her how she was, who had very bright eyes and white teeth and was Bethany’s father. Bethany was younger than Chloe but she knew so much more about everything.

Chloe went over to the car, peering in through the window he’d lowered on the passenger side.

‘Where are you off to? Going home? Jump in, I’ll give you a lift.’

Mr Norris never waited for an answer. She’d noticed that before. She didn’t know if it was because she was so slow or if he was like that with everyone.

‘I don’t need a lift.’

‘Course you do. You’ve got that heavy bag.’ He was smiling at her, his eyes fixed on hers. She stared at the bridge of his nose, unaware that it made her look slightly cross-eyed. ‘How come your mum didn’t pick you up?’

‘I can manage.’ It wasn’t a proper answer, and Chloe’s palms were wet from the fear he’d ask again, but there were good things about being thick and not having to answer questions properly was one of them.

‘Now you don’t have to manage. Stick your bag in the back and jump in.’

There was no point in arguing, Chloe knew. She trailed to the other end of the car and put her hand on the latch for the boot. It clicked and she tried to lift it. Nothing happened. She returned to the window.

‘It’s locked.’

‘Not the boot. Put it on the back seat, I meant.’ He bit off the ends of the words, obviously annoyed. And he hadn’t said the boot, Chloe thought, mortified. He’d said the back and she’d assumed he meant the boot. She’d got it wrong, as usual.

She fumbled one of the doors open and dumped her bag on the seat, then opened the passenger door and hesitated.

‘Get in. What are you waiting for?’ He was checking his mirrors, scanning the pavements. Getting ready to drive off, Chloe thought, remembering that and not much more from the three humiliating lessons that were the sum total of her driving experience.

She got into the car, scrambling to close the door and get her seatbelt on before he got annoyed again. He helped her with the seatbelt, smoothing it out carefully across her lap before he slid the metal tongue into the lock. The belt flattened the thin, sodden material of her T-shirt against her body and she thought he was staring at her chest for a second, but he wasn’t, probably. That was just her stepmother and what she’d said. He was a dad, after all. He was old.

‘So where’ve you been? Away somewhere nice?’

‘Dad’s.’

‘Oh yeah?’ Mr Norris went quiet for a minute, concentrating on the road. It didn’t occur to Chloe that he was choosing his words carefully. ‘See much of him?’

‘No.’

‘I’ve never actually met him.’

Chloe stared out of the window, not thinking about her father and the last time she’d seen him, not thinking about how angry he would be now, now that he’d realised she was gone. Not thinking about that took up all of her mental energy. He might have phoned her mother, she thought with a sudden lurch of fear. She hadn’t thought of that.

Mr Norris was talking, words filling the air in the car, telling Chloe about his weekend, about Bethany and what she was doing during the school holidays, about nothing that mattered to her. She stopped listening, drifting a little as the windscreen wipers sang across the glass, until something touched her knee – Mr Norris’s hand was on her leg. She stared at it in mute panic until he moved it away.

‘We’re here.’

The car had stopped outside her house, she realised, the engine still running.

‘You can get out here. I won’t make you run across the road in this weather.’

‘OK. Thanks.’ She reached down to push the seatbelt’s release button but he got there first. ‘Thanks,’ she said again.

‘No problem.’ He was frowning at her. ‘Chloe, love, are you all right? You look a bit—’

‘I’m fine.’ She pulled on the door handle and it didn’t open and her heart rate went spiralling up like a bird spinning through clear air but he reached across her and gave it a swift shove and it came open. His arm brushed against her chest as he drew it back, but that was just an accident, the contact brief.

‘Needs a firm hand.’

‘Oh,’ Chloe whispered. Her ears were hot, her pulse thudding so hard that she could barely hear him, but he was still talking. She got out of the car without waiting for him to stop, slamming the door on him. She turned to scurry up the path, glancing up at the house to see Misty in the window of the front bedroom, her paws braced on the glass, miaowing with all her might. The horn blared behind Chloe twice, very loud. It made her jump but she didn’t look back, her whole being focused on her need to go inside without saying anything else, or crying, one two three four five six seven at the front door eight nine ten eleven keys out twelve thirteen the right key in the lock and the door was opening and she almost fell through it into the narrow, long hallway but she got it shut behind her in the same moment and that was it, she was alone except for Misty, and she could collapse or scream or crawl into a corner and shake or chew her nails until they bled again or any of the things she’d been holding back for days now.

Misty hadn’t come down the stairs yet, she registered, and as if in response a thunder of scratching – sharp-clawed paws on wood – echoed through the still, silent house. The cat was shut in, then. Mum had shut her in. Chloe put her keys on the hall table. She should let the cat out.

Unless the cat wasn’t supposed to be out.

Chloe started towards the stairs.

Unless.

She stopped.

There was a mark on the wall. A big one. A smear, with four lines running through it like tracks. Chloe’s eyes tracked from the smear to the ground, to the droplets that ran down the wall and trickled over the skirting board and puddled on the ground. It was dark, whatever it was. Dirty.

Mud.

Paint.

Something that would make her mother furious.

Maybe that was why the cat was shut in, Chloe thought. Maybe that was it. Misty had made a mess. She started up the stairs, one hand resting lightly on the banisters, and it felt wrong, it was rough, as if something had dried on it, some more of the same dirt. Chloe looked down at it, at the stairs, and then at the hall below, and her legs were still carrying her up but her brain was working, trying to make sense of what she saw and what she felt and what she smelled and the carpet, the carpet was ruined in the hall upstairs, it was dirty and soaked and smeared and the pictures were all crooked.

Behind the closed door Misty set to work, digging her claws under the wood, splintering it as she scraped.

Let her out.

What had happened? The bathroom door was open but it was too dark in there, darker than it should have been. The whole house was dark. There was no reason to look, Chloe told herself.

She didn’t want to look.

… scratch scratch scratch …

Let her out.

Because if not, she’d damage the door.

Damage.

Let her out.

What …

Let her out, or there’d be trouble.

Chloe reached the door, and hesitated. She put out her hand to the handle, touching it with her fingertips. Behind the door the cat howled, outraged. She scratched again and the vibrations hummed across Chloe’s skin.

Let her out.

She turned the handle and pushed the door, and a grey paw slid through the gap, dragging at it to get it open, and Misty’s face, distorted as she pushed it through, her ears flat, her eyes pulled back like an oriental dragon’s as she forced her way to freedom. And then the door was open enough for her to rush through it to the hallway, and for the air inside the room to rush out along with her, dense with the smell of cat shit or something worse.

Before Chloe could investigate, the doorbell shrilled. It was loud, peremptory, and there was no question of ignoring it or hiding: she had to answer it. She hurried back down, narrowly avoiding the dark shape that was Misty crouching at the top of the stairs. There was a big smear up the door, she saw now, as she reached out to open it, a big brownish smudge that ended near the latch.

The bell rang again. Through the rippled glass she could see a shape, a man, his outline blurred and distorted. With a shudder, Chloe opened the door.

‘You forgot your bag, love.’ Mr Norris, with rain spangling his jacket, his tan very brown, his teeth very white. He held the bag out to her but she didn’t take it. She didn’t have time before his eyes tracked over her shoulder and took in the scene behind her and the genial smile faded. ‘Jesus. Jesus Christ. Christ almighty. What the—’

Chloe turned to see what he was looking at, and she could see a lot more when the door was open. A lot more. At the top of the stairs, Misty was still squatting, her eyes glazed and wild, her mouth open. Even as Chloe watched, she bent her head and gently, tentatively, began to lick the floor.

Behind Chloe, Mr Norris retched.

‘I don’t understand,’ Chloe said, and the panic spiralled again but she kept it down, held it back. ‘I don’t understand what’s happened. Please, what’s happened?’

Mr Norris was bent over, the back of his hand to his mouth. He shook his head and it could have been I don’t know or it could have been not now or it could have been something else.

‘Mr Norris?’

He had his eyes closed.

‘Mr Norris,’ Chloe said, very calmly, because the alternative was screaming. ‘Where’s Mum?’

2

I sat in the car, not moving. The rain danced across the empty street in front of me. It was unusual for it to be so quiet at a crime scene. Murder always attracted crowds, but the rain was better at dispersing them than any uniformed officer. The journalists were hanging back too, sitting in their cars like me, waiting for something to happen. Walking across the road would count as something happening, so I stayed where I was. The less attention I attracted, the happier I was.

The light wasn’t good, the dark clouds overhead making it feel like a winter day. I checked. Not quite six o’clock. More than three hours to sunset. Two and a half hours since the 999 call had brought response officers to the address. Two hours and ten minutes since the response officers’ inspector had turned up to get her own impression of what they’d found. Two hours since the inspector had called for a murder investigation team. Ninety minutes since my phone had rung with an address and a sketchy description of what was waiting for me there.

What I saw was a quiet residential street in Putney, not far from the river. Valerian Road was lined with identical red-brick Victorian townhouses with elaborate white plasterwork and black railings, their tiled paths glossy from the rain. The residents’ cars were parked on both sides of the street, most of them newish, most of them expensive.

The exception: a stretch about ten houses long where blue-and-white tape made a cordon. Inside it, police vehicles clustered, and an ambulance, the back doors open, the paramedics packing up as they prepared to move off. And halfway along the cordoned-off bit of street, a hastily erected tent hiding the doorway of the house that was my crime scene.

A stocky figure emerged from the tent, yanked down a mask and pushed back the hood of her paper overalls. Una Burt. Detective Chief Inspector Una Burt, acting up as our superintendent. The guv’nor. Ma’am. My boss. Her hair was flattened against her head: rain or sweat, I guessed. My skin was clammy already, the shirt sticking to my back, and I hadn’t done anything more energetic than drive across London on a wet Sunday afternoon. It was warm still, despite the rain.

Beside me, Georgia Shaw shifted in her seat. ‘What are we waiting for?’

‘Nothing.’

‘So let’s get going.’ She had her hand on the door handle already.

‘We are murder detectives. By the time we turn up at a crime scene, by definition, nothing can be done to save anyone. So what’s the rush?’

She cleared her throat, because when you’re a detective constable you don’t say bullshit to a detective sergeant. Not unless you know them very well indeed. Even if the detective sergeant is so newly promoted she keeps forgetting about it herself.

‘We’re not going to find the murderer by sitting in the car, though, are we?’

‘I once caught a murderer while I was sitting in a car,’ I said idly, more interested in the crime scene in front of me than in talking to the newest member of the murder team.

‘Who was that?’ Georgia narrowed her eyes, trying to remember. She had read up on me, she told me on her first day, and made the mistake of saying it in front of most of the team. If we’d been alone, I might have been able to be nice about it. As it was, I had turned on my heel and walked away, too mortified to say anything. I didn’t need to. I knew my colleagues would say plenty once I was out of earshot.

Some of what they said would even be true.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ I said now. Be nice. ‘Ancient history. The thing to remember is that it’s not a waste of time to take your time.’

Georgia smiled, but in an irritable stop-telling-me-what-I-already-know way. She was strikingly self-possessed for someone who’d been a member of the team for two weeks. Maybe it was just that I expected everyone else to be as diffident as I had been. Self-confidence had never really been my strong point but it was irrational to dislike Georgia simply because she was assertive.

It was a lot more rational to dislike her because she was absolutely useless. A graduate, she was on a fast-track scheme and had been moved to my team straight after her probation. She was young, she was pretty, she was articulate and confident and ambitious and not all that interested in hard work, it seemed to me. She was a filled quota, a ticked box, and I didn’t think she deserved to be on a murder investigation team.

Then again, that was exactly how the other members of the team had felt about me when I joined.

So I disliked her, but I sincerely tried not to.

Kev Cox emerged from the house, his face shiny red. He scraped back his hood and said something to Una Burt that made her smile.

‘Who’s that?’

‘Kev Cox. Crime scene manager. The best in the business.’

Georgia nodded, making a note. I’d already noticed that her closest attention was reserved for senior police officers – the sort of people who might be able to advance her career.

And a glance in my rear-view mirror told me that one of her prime targets had arrived, though the best thing she could do for her career was probably to stay far away from him. He inserted his car into a space I thought was slightly too small, edging it back and forth with limited patience and a scowl on his face. Not happy to be back from his holidays, I deduced. He had sunglasses on, despite the rain, and he was on his own, which meant he had no one to distract him.

And I suddenly had a reason to go inside. The last thing I wanted was a touching reunion with Detective Inspector Josh Derwent in front of Georgia. There was no way to know what he would say, or what he might do. He would have to behave himself at the crime scene.

At least, I hoped he would.

‘Let’s get going.’ I grabbed my bag and slid out of the car in the same movement. It took Georgia a minute to catch up with me as I strode across the road and nodded to Una Burt.

‘Ma’am.’

‘Maeve.’ Limited enthusiasm, but that was nothing new. I had been disappointing Una Burt for years now. Georgia got an actual smile. ‘Get changed before you even think about going into the house. We need to preserve every inch of the forensics.’

As opposed to obliterating the evidence as I usually do.

‘Of course,’ I said politely.

‘This is a strange one. Come on.’ She led the way into the tiny tent where there were folded paper suits like the one she wore. It was second nature to me now to put them on, to snap on shoe covers, to tuck my hair under the close-fitting hood and work my hands into thin blue gloves and settle the mask over my face. There was a rhythm to it, a routine. Georgia wasn’t quite as practised and I remembered finding it awkward when I was new. I slowed down, making it easier for her without showing her I’d noticed she was fumbling with her suit.

‘What’s strange about this one, guv?’

‘You’ll see.’

I looked down instead of rolling my eyes as I wanted to. Just tell me . . . But Una believed in the value of first impressions.

My first impression of 27 Valerian Road was that it was the kind of house I’d always wanted to own. It was a classic Victorian terraced house inside as well as out, long and dark and narrow, with coloured encaustic tiles on the hall floor and stained glass in the front door. I could have done without the blood streaks that skated down the hall, swirled on the walls, splotched the stairs and – I tilted my head back to look – dotted the ceiling. It was enough to take a hundred grand off the value of the property, but that still wouldn’t bring it into my price range.