Полная версия

How the Neonomads will save the world. Alter-globalism edition

How the Neonomads will save the world

Alter-globalism edition

Daniyar Z Baidaralin

© Daniyar Z Baidaralin, 2020

ISBN 978-5-4498-7296-8

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

ALTER-GLOBALISM EDITION

Many thanks to

The Spirit of the Great Steppe,

My dear wife Asylgul,

My loved brother Bakhtiyar,

Mr. Areke,

And those who influenced me!

INTRODUCTION

Why I wrote this book

The main massage that I am trying to bring across in this book consists of the following elements:

– The heritage and global impact of my ancestral Eurasian Nomadic Civilization is greatly underestimated, ignored, silenced, and even concealed from the modern humanity; and this is one of the most serious deficiencies of the modern world.

– Moreover, this unfair treatment of the Nomadic Civilization is preventing the humanity from solving the myriad problems we face today: ecological, societal, economic, moral, and technological.

– Only the Nomadic Civilization has the answers to all of these vast problems in the future. I proclaim that for the last four thousands years the majority of human civilization was moving in the wrong direction and that we must completely revise everything we know in order to survive and thrive as the species on planet Earth and in our Universe.

These are my strong life-long convictions, and I will try to defend my case in the following chapters.

I write these lines as I seat in a lockdown city of Almaty, Kazakhstan, hiding from the COVID-19 pandemic. The city is completely sealed by the joint forces of police, SOBR, and National Guard. This is the second week of the quarantine caused by the virus that shook the world. The world as we know it seems to be less certain than ever, and the grim future scenarios that have been around in the mass culture of the past decades appears to be unfolding right before our eyes. 1

We are not allowed to walk outside except for to buy food and medicine; while the schools, offices, malls – everything is shut down. Only the essential government services and food retailers are allowed to work, and the workers wear mask at all times. All of the work that could be performed from home has been switched to a distant online mode, otherwise the workers are on unpaid vacations or are being laid off.

Limited to my four walls and only short runs to a local minimarket, I have no longer an excuse to postpone writing this book, the ideas for which were brewing in my mind for a while. The gloomy occasion is suitable, for I am aiming at nothing less than to offer a path to save the world from self-destruction, and the pandemic is the exact manifestation of the sickness that I want all of us to cure.

Who am I and what are my qualifications? For more information about me read the Appendixes at the end of this book, but here I just want to give a brief.

I come from a few major historical and cultural backgrounds. Underneath it all is my favorite, original, native, Eurasian Nomadic heritage, for I am a Kazakh man born and raised in Kazakhstan, the Heartland of the Nomadic Civilization that existed here for at least three millennia starting from the 2 millennium BC. nd

On top of that, as a later addition that came about in the Middle Ages, I marginally represent the Central Asian Islamic realm. Skip forward, and my background is strongly influenced by the Russian Empire in the Modern Age and consequently the Soviet Empire in the 20 century. th

Now, in the early 21 century I spent almost ten years living in the United States of America, and this added one more dimension to my mentality. As of 2020 I reside in my native city of Almaty, the former capital of the now-independent state of the Republic of Kazakhstan, and where the COVID-2019 pandemic has caged me in my apartment. st

My educational background is in Fine Arts, Art History, and Architecture; all with a strong bias towards Eurasian Nomadic history, traditions and culture. My knowledge and skills are split between academic and practical. Most of my life I worked in a private sector of real economy: television, interior design, architecture, and construction.

At the same time I wrote a book on traditional Kazakh horseback archery, and I am now self-employed as a focusing on nomadic military and civil technologies. Today I spend my days researching about how the Eurasian Nomads made their armors, weapons, bows, arrows, clothes, shoes, horse equipment, and yurts; and then I build replicas and test them in field conditions to learn how it all worked back in the day. practical historical reconstructor

So why do I dare to write a book with such a loud and presumptuous name? I will make many bold statements in this book that might irritate, amuse, or raise eyebrows of my readers, but I ask you to bear with me. Thought I am not an accomplished academic or some guru, in my life I met many interesting, intelligent people of different backgrounds, and we had deep, wonderful, meaningful conversations that taught me a lot about the world we live in. We also partnered in some unique projects that helped me to advance my research and develop understanding of history, culture, religions, technology, and societies.

I am not as well-read as I wanted to be, for I don’t have much time to read and my reading list is three-miles long and I am way behind. But I possess a unique combination of educational background, specific knowledge, unique hobbies, and life and work experience that is not too common even in today’s interesting world.

Therefore, despite all of my shortages, I feel that I still have something to say to the world, and the time has come for it. Hence I wrote this book.

What is in this book and how to read it

This book consists of a few chapters, each of them devoted to a section of my overall statement, and the entire book is structured to be read as easily as possible, to my best abilities.

In chapter The Concept: Eurasian Nomadic Civilization I try to explain what the nomadic civilization was from the point of view of the native carrier of this culture to an outsider observer, because this is the biggest and most misunderstood chunk of human history.

In chapter The Concept: Nomadism vs Sartism I will explain the major conceptual differences between the nomadic civilization and the settled/industrial/post-industrial civilizations as they appears from my Post-Nomadic perspective.

In chapter The Concept: Future NeoNomadism I try to describe the alter-globalism model that I envisioned in my many years of research, observations, thinking, contemplating, and designing.

In chapter The Concept: Future NeoSartism I share my view on how the current post-industrial mode of our civilization must transform in order to become sustainable and stop destroying our planet.

In chapter The Concept: Big Picture I try to combine the two previous chapters and give the overall, universal picture of the future human society, its goal, purpose, and further development in the foreseeable future.

In chapter The Concept: Long-Term Future I outline my vision for the big steps that the humanity must undertake in the next few centuries.

In chapter The Concept: How to Get There I hint as to where we can start implementing the NeoNomadic theory and about the need of a pilot project.

In chapter Conclusion I try to express all of my thoughts in a brief format and finalize this book.

In Appendixes I put all of the information that I thought might make the reading of the main chapters less smooth, but which a reader might find interesting after reading the chapters first. In contains information about me, my influences and sources, the controversy of the terms «NeoNomadism», quick facts about the Eurasian Nomads, and etc.

Read first, criticize later

I understand that many of the ideas in this book are so new and wild that they most likely will be met with some resistance and distrust, to say the least. Perhaps, many will simply dismiss it as a nonsense. However, if one will find it interesting, but not convincing, I urge you to read the whole book first and criticize later, because I tried to foresee the most common questions and doubts, and answer them in advance to my best ability.

Free PDF presentation

Also, if you e-mail me at dbaidaralin@gmail.com, I will send you a free PDF presentation that provides a visual aid for this book.

THE CONCEPT: EURASIAN NOMADIC CIVILIZATION

Concept

Nomadic pastoralism

There is an enormous amount of misunderstanding about the nomadic civilization of the past few millennia. Moreover, the general view on the Eurasian Nomadism is the single biggest misconception known to me within the entire body of human knowledge. It is a complete 180 degree opposite of what it really was historically.

In order to understand the depth and breadth of this misconception, I will have to give a brief crush course on traditional nomadic lifestyle. This is not a history textbook, but it would be impossible for me to explain my theory without diving into the past and giving a clear picture of what the nomadic civilization was like in reality. I will try to paint it with a broad paintbrush in the chapters, and get into more details in Appendixes.

The traditional understanding shared by all cultures in the West and East, paints the historical Eurasian Nomads as vicious, wild, blood-thirsty barbarians, barely humans at all; the orc-like creatures that come and burn, plunder, loot, pillage, rape, and destroy the hand-made miracles of the hard-working settled nations. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam associated the nomads with Gog and Magog, the mythical wild beasty people who will attack the humanity and bring the world to the brink of extinction.

Nobody likes the Eurasian Nomads (EN). They are the classical «bad guys» in human history, who only bring blood spillage, tears, grief, and despair. The Scythians who plundered the Middle East and Egypt in the BC, the Huns who destroyed the Western Roman Empire in AD, the Turkic tribes that terrorized the world in the early Middle Ages, the so-called Mongols who crushed everybody and created the biggest land empire of all times. Most people know of the «maniac» Attila the Hun, or the «bloody-eyed genocidist» Genghis-Khan.

And the humanity have tried to ignore or forget them, just like a victim of violence tries to forget the violator. But in doing so, we made a big, fundamental mistake that is haunting and hurting us ever since. And we will never be able to fix our problems, unless we right the wrong.

The truth is: the Eurasian Nomadic Civilization (ENC) is one of the two parents of the modern human civilization; the other being the Settled Civilization (SC). The ENC was buried a few centuries ago and we prefer to either never remember about it, or at least to never speak of it other than of a monster. In the meantime, the nomads gave the world many important things, such as governments, statehood, metallurgy, horses, saddles, stirrups, high boots, trousers (pants), topwear dresses, horseback archery, cavalry, wheels, chariots, yurts, felt, rugs, and many more things. I describe this impact more in detail in Appendixes.

The real role of the EN global influence is exactly opposite of what is perceived by most in the modern world. My ancestors were the balancers of the nature, their lifestyle was ideal for ecosystems. I fact, they were the integral part of the Great Eurasian Plains called the Great Steppe, that stretched from the flats near the Altai Mountains to Eastern European Plains. The nomadic model of economy appeared in these lands only because no other type of economy with pre-industrial technology was possible in these barely habitable lands.

The nomads lived in constant migration cycles, following their herds and chasing the seasonal grasses on pastures. They move in a certain way year after year, decade after decade, century after century, and millennium after millennium. Their ethnic composition, the anthropology, language, faiths has changed over the millennia, but the lifestyle remained practically the same. The EN societies closely mimicked each other in their economic and technical aspects, because they were built-in within the nature and were limited to only one possible way of survival: the nomadic pastoralism.

The EN peoples were never as numerous as the SC peoples. The harsh lifestyle, lack of infrastructure, limited technologies and economic powers, and scarce resources never allowed the EN states to flourish to the same extent as their settled neighbors. But this lead to a lifestyle and mentality of valuing only the essential, vital things in life. Even the SC neighbors who severely disliked the nomads admitted that they were the most noble and honest people, albeit brutal and cruel out of necessity.

The main wealth and the economic engine of the ENC was their cattle. The cattle-breeding was the one single most important feature that dominated all aspects of the nomadic life in the times of peace; and in reality peace was the most common state of affairs. Usually the nomads only succumbed to war in extraordinary turns of circumstances, but a vast majority of time they were peaceful and friendly herdsmen. Cattle was the gold of the nomads: they never sold their sheep, camels, or horses for money in order to keep their wealth in coffins. Quite the opposite: they let the beasts roam free in the open fields, only protecting them from the packs of wolves and cattle-thieves. The wealth of the nomadic nations was in their herds: the bigger, the better.

Nomadic hunter-gatherers, Settled Civilization, and the Eurasian Nomads

In order to differentiate the Eurasian Nomads and other nomads, we need to look at some popular misconceptions regarding the phenomenon of nomadism in general.

The most common understanding of the nomads in history is that they were a mistake, a historical evolutional dead-end, an annoyance that must be dismissed and forgotten as soon as possible. At this, many don’t make an important distinction between the nomadic hunter-gatherers, African nomads, Middle-Eastern nomads, modern stateless nomads such as Romani (Gypsies), and the Eurasian Nomads.

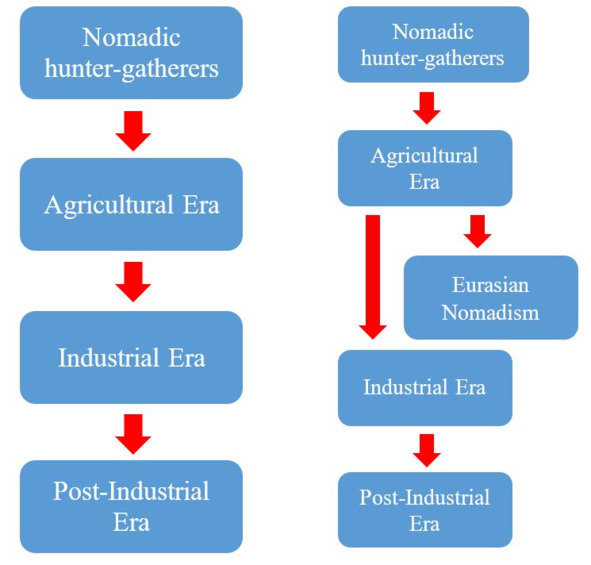

The common scholarly view in terms of the human society’s evolution suggests that the first humans were nomadic hunter-gatherers, then these peoples discovered agriculture which led to the Agrarian Revolution and the Agrarian Era, which then led to Industrial Revolution and the Industrial Era, and now we live in the Post-Industrial Era.

The Eurasian Nomads are simply not included into this linear process, as if they never existed, nor they ever created any significant states. At the same time, there are plenty of history books on nomadic empires from Scythian and Hun to Turkic and so-called Mongol. I write more about the history of the nomadic states and empires in Appendixes.

At best, nomads are equaled to the primitive nomadic societies of early hunter-gatherers who precede the agrarian societies. Such is the sad state of things in the modern human knowledge. The nomads are gravely underappreciated, their impact is minimized and their know-hows are unfairly forgotten. Only a handful of nomadologists know the truth, but their voices are never heard by general public.

At the same time, according to the growing number of scholars who study the ENC, the picture of the human society’s evolution looks different from what I described above.

This is what we’ve learned so far about the Eurasian Nomads. After the nomadic hunter-gatherers evolved into agrarians, the later formed first states along the river banks all over Eurasia, where the climate allowed for agricultures to flourish. But the fertility of the arable lands was limited, and the existing technology only allowed for a certain amount of product per area. As the numbers of population grew and also possibly due to the climate changes that diminished the productivity of these lands, some of the agrarians were forced to live in worsening conditions, with hunger threat being imminent.

Fortunately, these changes happened slowly enough for people to adapt. As a result, some people learned to rely on cattle-breeding at first as a subsidiary, and later as a substitute alternative to agriculture. Thus the first semi-nomadic economic models appeared, where parts of extended agrarian families were part-time or mainly cattle-breeders. Later on this specialty lead to a development of seasonal pastoralism, where some families would drive their herds to summer pastures and only return home for winter.

The herds grew in numbers, providing the herdsmen with meat, fats, dairy, wool, and leather. These goods were then exchanged for products of agrarian economy in settlements, thus giving the nomads what they couldn’t produce on their own. This early exchange of goods signified the future relationships between the nomadic civilization and settled civilizations in Eurasia that remained valid until the 20 century, and even still exist today in Mongolia and Northern China. th

Soon enough the herdsmen invented ways of full-time, year-round pastoralism. After a few generations, the families of herdsmen gradually became fully independent, and started developing their own type of society, with independent chiefs, military, courts, and other societal institutes. Some even went as far as to completely severe their ties with the agrarian relatives, others tried to live close to them and trade. This allowed for greater freedom in choice of pastures and grasslands, and led to full-blown nomadic pastoralism, which I call the Nomadic Revolution.

The Nomadic Civilization: modern perception (left) vs true science (right)

The ENC was born in the Bronze Age, it stemmed from the agrarian society, and it existed in parallel to SC for three millennia. And it was successful! There are numerous historical facts that clearly spell the advantages of the ENC over the SC. When the nomads were on the rise, they built their empires in a blink of an eye, and no SC nation could resist them. And they’ve done it time and again, century after century, for thousands of years. Many European, Middle-Eastern, Slavic, Russian, Chinese, Indian, and Iranian dynasties were EN in origin. Please read Appendixes for more detail.

Only in the Modern Era the advancement of technologies and following growth of economic powers allowed the SC nations to finally stall the advancement of the EN, and then gradually turn the tide and start pushing them back into the Great Steppe. Particularly helpful was the invention of gunpowder weaponry, which lead to a mass supply of cheap SC soldiers, who were able to overwhelm the elite EN cavalry.

This process was helped greatly from inside the ENC by endless civil tribal wars that weakened the EN. But even then this process took a few centuries. The EN society was so strong and resilient that it was able to resist the growing powers of the SC nations, which surrounded the Great Steppe from all directions by an ever-tightening rim. Russia was pushing from the north, China from the east, Central Asian Islamic states from the south, and Iran and Europeans from the west. I call it the SC Rim.

Finally, it seemed that the ENC was finished, and finally met its evolutionary dead-end. The SC, finally ridding of the millennia-old threat, proclaimed an ultimate victory, and the ENC was forgotten and written off from the history of humanity. Such was the great fear that even today, after the ENC seized to exist, only a handful of scholars know the truth that remains hidden from the majority.

But is the Nomadic Civilization really dead, forever? I dare to beg to differ and am going to argue this point further in this book. Not only I believe that the history of the NC is far from being over, I even think that this is the only possible way for the humanity to evolve in the future, and remain relevant and prosper.

Economy

Cattle-breeding economy

In order to understand the nomadic civilization better, we need to first understand its economics. It’s fairly simple in the core: the cattle, mostly sheep, horses, and camels, and sometimes goats and cows, eat on wild grasses of the seasonal pastures. As the pastures run out of grass due to overgrazing and drying from seasonal temperature rises, the cattle is moved to next pastures that are still full of the fresh grass. This keeps cattle alive and multiplied in numbers by breeding.

The nomads basically simply follow their cattle herds, and make sure it happens in an organized manner. This closely mimics the great animal migrations in Africa, where millions of zebras, antelopes, and other animals move in the same manner chasing the seasonal pastures. But in the Great Steppe, this took a more structured, man-made form. The herdsmen watch after their cattle, defend them from wolves, cattle-thieves, and other dangers. They also ensure to pick the best routes with watering places, and ward off any possible threats, allowing the herds to roam in a relative comfort.

In exchange the cattle provides the herdsmen families with meat, fats, dairy, wool, leathers, bone, sinew, horns, hooves, and other valuable materials that sustain human lives and production, and feed the economy. The nomads were always careful in using their live wealth, and made sure that not a single fiber of wool goes to waste. The nomadic consumption of cattle was 100% waste-free. Even the cattle dung was dried, stockpiled, and used as fuel to make fire.

Some of the EN always led semi-nomadic lifestyle in areas of the Great Steppe where such economics were possible. One of them being the region where I live – the Almaty Oblast, or Jetysu Region (the Seven Waters in Kazakh language). This region has high mountains and flat steppe right next to each other, creating a unique landscape. The mountain footings in the south of Almaty City allowed for agrarian economy, while the plains in the north were ideal for nomadic pastoralism; all within a few miles distance. Also there were pockets of fully-agrarian societies that lived among the Eurasian Nomads too.

The cattle was, of course, the main source of food. Meat was consumed regularly and by all nomads regardless of their social status; unlike that of the SC nations where meat was a privilege of the rich and powerful. The cattle also supplied the nomads with dairy products: most prominently the delicious fermented horse milk called and gourmet camel milk called , along with many others. In Mongolia, where the local nomads traditionally have more cows, they make many types of dairy products from cow milk, such as , and a few types of milk alcoholic beverages. qymyz shubat airan

This is the basic nomadic economy in a nutshell. It was not complicated in principle, but of course it required tons of expertise on a practical level. The nomads knew everything there is to know about their cattle, given the pre-Industrial technologies. They knew when to move to new pastures, best routes, watering holes, mating and breeding times, sicknesses and cures, as well as the best ways to shear, slaughter, and cut meat. The nomadic cuisine in a pure form contained mostly meat and dairy products, of which the nomads invented many delicious dishes. These dishes were enriched with either natural foods, such as plants, roots, fish, and etc., or with what the nomads could trade off with the SC nations: grains, vegetables, and etc. I write more about the nomadic traditional cuisine in Appendixes.

Nomadic production

The Eurasian Nomads developed their own way of production and industries. Some were advanced and happened for the first time in the Great Eurasian Steppe. For example, the metallurgy. The EN were the first to discover large deposits of metal ore in Altai, Central and Northern Kazakhstan. Most of them are still being extracted today on an industrial level.