Полная версия

Mother to Mother von Sindiwe Magona. Königs Erläuterungen Spezial.

In 1953 the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act defined racially-specific public services, such as hospitals, universities and public parks, which were not allowed to be used by members of other races.

Also passed in 1953, the Bantu Education Act segregated national education, effectively cutting black South Africans off from the better-financed and organised educational infrastructure, which was from this point on only available to whites.

In the 1950s the government also created the “pass laws”, which stopped black South Africans from being able to travel freely in the country. The pass laws in particular limited blacks’ ability to enter urban areas; black South Africans were now required to provide authorisation from a white employer to be able to enter specific towns and cities (when China vanishes, Mandisa first believes he may have been arrested for just this crime: “Maybe he had been arrested for a pass offence”, p. 144).

These laws led to the forced relocations of the 1960s–1980s, during which millions of non-white Africans were removed from their homes and made to live in so-called “tribal homelands” – although these areas often had no historical validity or relevance for the tribes. These regions were also largely unsuitable for larger populations, with very poor agricultural potential and little or no infrastructure. Some of these so-called bantustans became independent republics. The goal of the white supremacist governments was to strip black Africans of their South African citizenship as they moved into the bantustans, thus removing all remaining rights from the blacks and freeing the white rulers of all remaining responsibility for the blacks.

Petty and grand apartheid – Very broadly speaking, apartheid in South Africa came in two forms. Petty apartheid is the segregation of public facilities (hospitals, public toilets, churches, public transport etc.) and social events, meaning that blacks and whites are not allowed – by law – to share these facilities or to mix with one another in “social events”. Grand apartheid is concerned with housing and employment. So the relocations which play such a huge role in Mandisa’s youth are an example of grand apartheid: the government telling her and her family where they are allowed to live (see p. 28, where Mandisa describes the shock of being relocated to Guguletu). Black labour was necessary to uphold South Africa’s industries – particularly mining – because the blacks could be exploited with poor wages, little or no labour law protections, and inadequate security for dangerous jobs. This government control of work is also a case of grand apartheid.

The apartheid system was hugely controversial and widely denounced all around the world. As well as activism and resistance within South Africa, there were global movements aimed at stopping and removing the institution of white supremacy as state policy. Many countries joined in arms and trade embargoes against South Africa. In 1973 the United Nations officially defined the apartheid system as a crime against humanity, which would allow criminal prosecution of individuals responsible for upholding and enforcing the system. Not all member states signed the declaration: by 2008, nearly 90 states had still not signed.

Sport under apartheid – The world of sports is not relevant to Mother to Mother, but a brief look at the subject highlights the injustice and absurdity of white supremacist policies on a social as well as international level. Because the apartheid system forbids multiracial sports teams, it was almost impossible for teams from other countries to play any kind of sports in South Africa. No teams were permitted to compete if they contained members of different races.

The International Table Tennis Federation cut all ties to the South African table tennis organisations in protest. South Africa was banned from the 1964 Olympics, and again in 1968.

The Australian Cricketing Association refused to compete in South Africa or against South African teams as long as they selected their teams on a purely racial basis. In the Chess Olympiad of 1970, the Albanian team forfeited rather than face a team of chess players from an apartheid state. South Africa was suspended from FIFA (the international governing body for football) in 1963. The South African tennis team was banned from the 1970 Davis Cup tournament, and when they were allowed to participate in 1974 they won because the Indian team refused to travel to South Africa to compete in the final.

Following the end of apartheid in 1991, the various boycotts against South African athletes and teams also quickly ended.

By the 1980s increasing number of Western companies and organisations were withdrawing from South Africa in response to louder and louder calls for boycotts and embargoes, taking their money with them, and this, combined with structural flaws in the South African economy, was having a devastating effect on the country. These economic pressures combined with increasingly potent and at times violent resistance within the country, as militant and activist groups grew bolder and angrier. Under increased pressure from within and from the rest of the world, the South African government began to release anti-apartheid political prisoners, which further electrified and revitalised anti-apartheid activism within the country as these political prisoners – or, in the phrase made famous by Amnesty International, “prisoners of conscience” – were welcomed back as heroes and martyrs by the anti-apartheid movement.

Attempts made by the central government to reform apartheid – such as giving “coloureds” and “Indians” voting rights in 1983 – were widely seen as inadequate responses to the problem. The government under P. W. Botha (1916–2006, leader of South Africa from 1978 to 1989) claimed it was about to make reforms to the apartheid laws which never came true.

By the end of the 1980s the South African economy was in terrible shape, and when Botha suffered a stroke and resigned as leader, F. W. de Klerk became the leader of the state, and moved quickly to begin dismantling the discriminatory legislation underpinning apartheid. The changes he initiated included lifting the bans on anti-apartheid groups and organisations like Nelson Mandela’s ANC (African National Congress). De Klerk also ordered the release from prison of Mandela after 27 years, restored the freedom of the press and suspended the death penalty. De Klerk was the country’s president in 1993, when the contemporary events surrounding the murder of the white girl are described in the novel.

The end of apartheid was finalised in a series of negotiations in the years 1990 and 1991, ending in the general elections of 1994 (a year following the events described in Mother to Mother), the first time in the country’s history that all South Africans were allowed to vote. The process was violent, with both “black on black” violence erupting all over the country as well as white supremacist attacks on anti-apartheid activists and even assassinations of anti-apartheid leaders. The negotiations were repeatedly interrupted by protests from groups and organisations representing the far-right white racist minority. The violence continued right up until the day of the general election, with car bombs exploding and people being killed. On April 27, 1994, the apartheid state officially ceased to exist, and South Africa raised its new flag and sang the new official national anthem, “God Bless Africa”.

The novel is very much about the apartheid era – about the forces (racism and colonialism) which made it possible, the terrible consequences it had for society as a whole, and for tribes, families and individuals. Sindiwe Magona is a generation older than her main character, Mandisa, and Mandisa’s experiences are based on Magona’s own life, specifically the places she was forced to live and the pressures on her as a black woman and a young mother. Magona was born in 1943 and witnessed the apartheid era in its entirety; as an adult she campaigned ceaselessly from the UN in New York for an end to apartheid.

The Xhosa

Mandisa and her family (and the other African characters we see in the novel) are all Xhosa. There are 8 million Xhosa people living in South Africa (roughly 18% of the population, according to the 2011 census). They are an ethnic sub-group of the Bantu peoples, which is the umbrella term for the hundreds of ethnic groups in Africa who speak variants of the Bantu languages. The language spoken by the Xhosa is called isiXhosa, and it is the second most commonly spoken language in South Africa (after Zulu).

During apartheid, the Xhosa were denied South African citizenship, and were instead allowed to live in self-governed so-called “homelands”, called Transkei and Ciskei.

The cattle killing movement: “The hatred has but multiplied.”

The cattle killing movement of 1854–1858 was a near-catastrophic act of self-destruction committed by the Xhosa, based on a prophecy by a young girl. Cattle introduced by the white settlers had spread new diseases to the native cattle, many of which died. The loss of cattle – which were for the Xhosa an important status symbol as well as being a source of food and leather (see pp. 176–177) – was a serious problem. The girl, Nongqawuse, told her father that she had encountered spirits out in the fields, and that they had told her that the Xhosa should kill all of their cattle. The spirits of all the dead Xhosa would then return to drive out the white settlers, and bring back all the cattle with them (p. 180).

Her prophecy made its way to the chief of the Xhosa, who ordered the tribe to kill all their cattle and destroy all their grain supplies. Some Xhosa allegedly believed the prophecy to be genuine, and some simply followed orders. Whatever their reasons may have been, the results were disastrous. Famine struck, the Xhosa had no food, the prophesied return of the ancestors never happened and the dead cattle never reappeared. Instead, the white European settlers were forbidden by their governor Sir George Grey from helping the starving, helpless Xhosa unless the tribespeople signed labour contracts with the white landowners. The Xhosa were then bound to work in the mines, labouring for the white colonists.

This is told to Mandisa by her grandfather Tatomkhulu (see Chapter 10, pp. 175–183). A true story and an important episode in Xhosa history, the story has additional significance to the novel. Mandisa has been taught that the Xhosa followed the prophecy because they were “superstitious and ignorant” (p. 175). But her grandfather teaches her that it was an act of desperation, fed by their hatred of the white settlers who had stolen absolutely everything from the native peoples of the country they had colonised – a colossal, catastrophic act of self-harm. Mandisa comes to believe that the story reveals something honourable rather than merely being a display of disastrous ignorance. Her grandfather positions it in a sequence of protests and uprisings against the white settlers through the colonial history of South Africa, pointing out efforts by the black inhabitants of the country to reclaim their land which had been stolen from them, and to resist the “button without a hole” – meaning coins, because money was unknown to pre-colonial South Africa – because of the damaging effect money would have on a purely agrarian culture.

The symbolism of this history of honourable but doomed protests and violent, apocalyptic uprisings against the hated white oppressors is of great relevance to the tragic story of the killing of the white girl in Guguletu – the story at the heart of Mother to Mother. The same hatred of colonists who had stolen everything can be seen in both the cattle killing movement of 1857 and the “one settler, one bullet!” war cry of the furious anti-apartheid protests of the 1980s and 1990s, and the mob who killed Amy Biehl.

Rites of passage and traditions: Marriage, parenthood and gender

We see different examples of traditional customs and rites of passage in the novel, and learn about the traditions which organise marriage, the business of parenthood and the roles and interaction of men and women. These traditions are seen with a degree of ambivalence: While Mandisa is frustrated by the unfairness of the limits imposed on her as a woman and a young mother, and is equally annoyed by the dominance allowed to males within the culture, she also sees how a lack of traditions and respect for customs and cultural roles can damage and break a society.

We will look at the role played by traditional initiation rites and customs in the chapter on themes in the novel (see p. 100). These include:

Marriage arrangements and ceremonies

Circumcision and coming of age rites for young men

Naming customs

The patriarchal structure of tribal society

Tribal legends and myths

Faith healers (Sangomas)

Education and politics

“Boycotts, strikes and indifference have plagued the schools in the last two decades. Our children have paid the price.”

(Mandisa, p. 72)

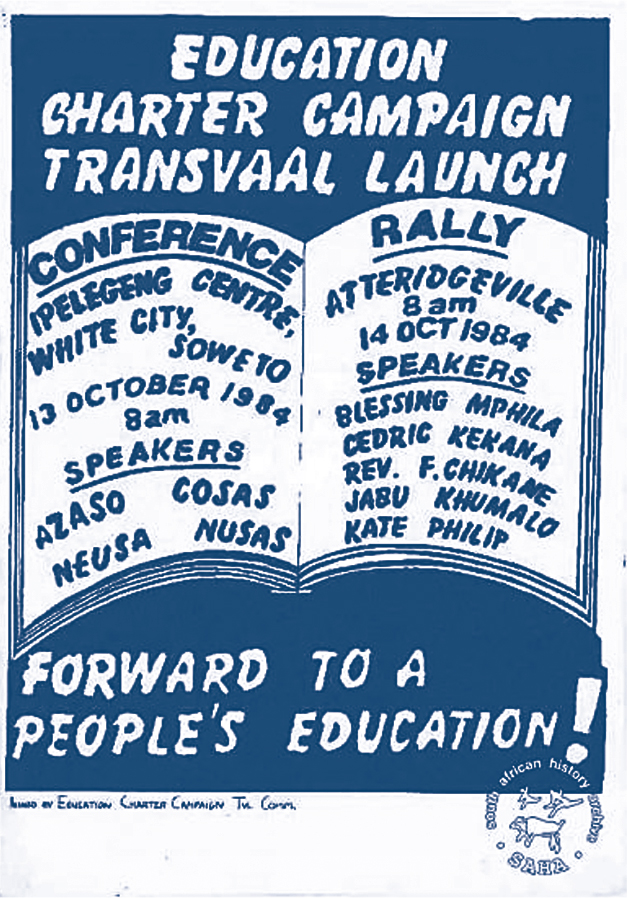

Poster from 1985 protesting and demanding reform of the education system.[5]

The combination of inadequate education, social neglect and bad politics (at once irresponsible, oppressive politics proved to be explosive in the immediate aftermath of the apartheid regime. The protests and explosions of violence which Sindiwe Magona talks about in Mother to Mother were shocking to many – to locals and neighbours as well as outsiders and foreign observers.

The apartheid system influenced education as well as every other aspect of life in South Africa. From the early 1980s, black schools were legally required to conduct the majority of their lessons in English and Afrikaans, with the native languages only allowed to be used for subjects like art and music. The government’s goal was to make sure that all black people in South Africa knew how to communicate with white people in “white” languages. There were widespread and at times violent protests against this, as many students didn’t want to speak Afrikaans. There were strikes and boycotts of schools throughout the townships.

Multilingual colonial societies have an interesting side-effect when it comes to languages. Organising a society along racial lines – as in apartheid South Africa, with whites on the top and blacks on the bottom – and enforcing the language(s) of the minority ruling class means that the lower classes are forced by circumstance and by law to learn the colonisers’ languages. But they also grow up speaking their own tribal language. In the case of the black characters in Mother to Mother, that language is Xhosa.

The result of this structure, with black native languages forbidden from being taught in schools but being the main form of communication at home, is that the blacks grow up speaking at least three languages – a tribal mother tongue, English and Afrikaans – whereas the white ruling classes will usually be limited to speaking only the official “white” languages.

The fluid ease with which Mandisa and her family switch between these languages and the interesting way in which the languages interact with and influence each other are looked at in this study guide in the chapter on Style and Language (p. 114).

The quality of teaching was also an issue. Over 90% of all the teachers in white schools were properly trained and certified teachers[6] whereas only about 15% of the teachers in black schools were trained teachers. The pass rate for exams and graduating among black students was less than half what it was for white students.

The issue of education is very important in Mother to Mother – Mandisa talks about it on pages 71–72, for example – but more as a matter of context and environment. It is another one of those outside influences contributing to the violence and unrest of the society and more specifically to Mxolisi’s development and behaviour as a young man. The generally low quality and restrictive nature of segregated education in the apartheid state had the effect of increasing ignorance, unemployment and despair throughout the black population. With no real education – we can see how Mandisa is constantly frustrated in her efforts to educate herself – people have no chance to get well-paying jobs or to improve their position within society. The lack of perspectives creates more despair and frustration, on the one hand: and on the other hand, it provokes radical and at times violent resistance and protest.

The student protests

The school boycott was sparked by the deteriorating quality of education in black schools, the school age limit of twenty, and the policy that denied students representation by a democratically elected Student Representative Council.[7]

The student protests of the “Young Lions” in 1993 which Mandisa talks about were part of a long tradition of protest and resistance, but in this year they were particularly energized by the frustratingly slow pace of change and improvement in society and politics following the release of Mandela, among other developments. Mandela had called the Young Lions “the government-in-waiting”[8] because so many of their leaders were gifted, intelligent and energetic individuals who spoke passionately and articulately about the need for change in South Africa and an end to the oppression of the blacks. But many of these young people had come out of a nation-wide movement which had boycotted schools, protesting the state-led efforts to keep the black population in a state of passivity and ignorance.

While many of these young people wanted to become lawyers or politicians and active, professional members of society, most of them had little or no official education. Mandisa first mentions the student protests and education boycotts on page 10, describing how a student organisation (COSAS) told students to boycott schools out of solidarity with striking teachers. For Mandisa, this playing at politics and social unrest is unreal, a dangerous and stupid game which is stopping the young people from understanding life – as she sees it, by wasting their youth and not going to school, they all but guaranteeing that their lives as adults will be no better than her generation’s: “if they’re not careful, they’ll end up in the kitchens and gardens of white homes … just like us, their mothers and fathers” (p. 10).

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Sindiwe Magona has written a two-volume autobiography (the first part of which was her first published work), a biography of Archbishop Ndungane, as well as short story collections, poetry and novels. She has also written more than 100 books for children – we won’t be looking at these in this study guide, however.

The novels

PUBLICATION DATE TITLE 1998 Mother to Mother 2006 The Best Meal Ever 2008 Beauty’s GiftMother to Mother was Magona’s first published novel, and it remains her most famous and successful work. The Best Meal Ever is set in a South African township and is about a girl having to look after her younger siblings. Beauty’s Gift is a novel about a group of women and how they deal with the HIV/AIDS-related death of one of their circle of friends.

Short story collections

PUBLICATION DATE TITLE 1991 Living, Loving and Lying Awake at Night 1996 Push-push! And Other StoriesAs with her novels, Magona’s short stories draw on her personal experiences and are all concerned with South African social issues, in particular those affecting women.

Poetry

PUBLICATION DATE TITLE 2009 Please, Take PhotographsAutobiographies

PUBLICATION DATE TITLE 1990 To My Children’s Children 1992 Forced to GrowTo My Children’s Children, Magona’s first published work, is an open letter to her grandchildren in which she tells the story of her own life up to the age of 23, and shares what she can of Xhosa culture and traditions. She presents herself explicitly as a “Xhosa grandmother”, and the book is of interest as a personal memoir, as an eyewitness account of the apartheid era, as an anthropological study of Xhosa tribal customs and folklore, and as a study of how women of all ages suffer and are oppressed under patriarchal social systems. Forced to Grow continues her autobiography from the age of 23 on.

Biography

PUBLICATION DATE TITLE 2012 From Robben Island to Bishop’s CourtThis is a biography of Archbishop Njongonkulu Ndungane, who was a pioneering anti-apartheid activist who was imprisoned on Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela also spent many years in prison. After being released from jail he continued to work to end apartheid, and campaigned for the rights of HIV positive people, equal rights for women and protecting the poor and dispossessed.

Children’s books

PUBLICATION DATE TITLE Not yet published The Stranger and His Flute, Greedy Man, Kind Rock Nokulunga, Mother of Goodness Stronger Than Lion Buhle, the Calf of Many Colours The Woman on the Moon