Полная версия

Why Europe Should Become a Republic!

Part III begins with a brief excursion into art history. The subject is the myth of Europe (or Europa), and it is written with a conspiratorial wink to my sisters – because of course Europa is a woman. The reason why it is important for the coming European project to bear this fact in mind is explained there. After that, we cast a glance at the young people of Europe, who have long begun creating, from the bottom up, a radically democratic Europe of a kind that Brussels could not conceive of in its wildest dreams. Finally, we set out briefly why, if it does eventually prove possible to establish the European Republic, this European project of a deep post-national democracy should be seen as the blueprint for a global citizens’ republic – which is something we need to build before planet Earth is finally destroyed. Or before more intelligent beings6 are obliged to show us the way!

* * *

CHAPTER 1

The European Malaise

‘Not enough Europe, not enough Union.’

Jean-Claude Juncker

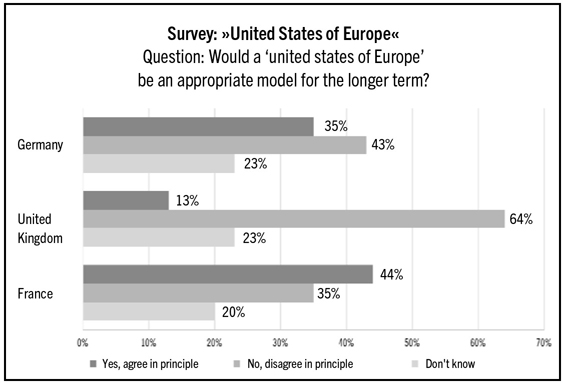

Anyone who talks to the citizens of Europe these days, from Helsinki to Athens, from Prague to Rome, from Budapest to Warsaw, hears two things: a deep dissatisfaction with the EU, and a deep desire for Europe. Somehow, people have a shared cultural memory of Europe, and within it is the idea that we all belong together. To most people it is clear that the European nation states have no hope of making it on their own in a globalised world. The majority of all EU citizens, around two-thirds, still supports the idea of Europe. These people don’t want to lose Europe. Many of them are deeply worried right now that the European project could fail. More than that, they are scared. But they no longer trust the EU. Over the last few years, this loss of trust has amounted to about 20 per cent on average across Europe. The EU has forfeited the trust of most of its citizens. Only about 30 per cent of the German, French and British populations – that is, of the three largest EU member states – still support the project of a ‘united states of Europe’.

Yes to Europe, no to the EU. That’s the general feeling. What they want is a different Europe. But this other Europe is not here yet; it has to be invented – a democratic and social Europe. A Europe of citizens, not of banks. A Europe of workers, not of businesses. A Europe that acts in concert in the world. A humane Europe, and not one that shuts itself off behind barriers. A Europe that defends its values rather than trampling all over them. This Europe doesn’t exist.

The betrayal of the European ideal by the nation states is almost physically painful. The betrayal of human rights, first drowned in the Mediterranean, then trampled into the mud of the Balkan route. The most recent of the ongoing and fast-moving developments in the refugee crisis could not be taken into account in this manuscript, which was completed at the end of January. So I would just like to add here, following the EU Council meeting of 7 March 2016, that the unseemly haggling being carried out on the backs of the refugees, and against the backdrop of the humanitarian crisis in Idomeni in Greece (Germany and Europe cosying up to Turkey, the de facto agreement to support Greece financially while transforming it into a kind of European Lebanon – anything, so long as the refugees are no longer allowed to reach the Balkan route), can only be described as deplorable. The betrayal of the promise of a political union, suffocated in the endless hot air emitted by the Brussels technocrats. The betrayal of the idea of a Europe without borders, now impaled on fences. The betrayal of the idea of overcoming nationalism and populism, both of which have come back with a vengeance. The betrayal of the dream of a social Europe, of a converging European economy as foreseen in the Maastricht Treaty, swept aside by the neoliberal Single Market. The betrayal of the next generation, and the one to follow, who have been burdened, via the socialisation of bank debt, with the costs of a scandalous, shameless binge on the financial markets. The betrayal of the savers, whose savings and life insurance policies are being eaten away by low interest rates. In recent years, the EU has created many losers and only a few winners – but very big winners.

As a result, few things are as fragile as the European narrative today. 50 years of European integration now seem like a thin veil which is being torn back to reveal a historical abyss threatening to swallow up Europe once again. An EU incapable of reform, almost apathetic, now produces only endless and growing crisis. Clearly the EU, with its multiple integration projects, has lost its way. First, the Single Market project; then, Economic and Monetary Union. Lately there has been a concerted but fruitless effort to bring about a Common Foreign and Security Policy. Yet it is clear that the EU has managed to lose the very thing needed to inspire popular enthusiasm for the project of a common Europe: the essence of politics.

The death of political Europe can be sketched out in a few sentences. The Maastricht idea of an ever-closer union had fizzled out already by the end of the 1990s. The Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) has not worked. The emancipation of Europe from the USA has not succeeded: what remained of it was buried in the confusion wrought by the American war on Iraq in 2003, where the slogan of ‘united we stand’ succeeded only in uniting the eastern Europeans against the German-French tandem. From that point on, a deep division has split the EU in two. As was often said in the 1990s, enlargement and deepening could not be undertaken in parallel. Maastricht and Amsterdam, Nice and Laeken are all European place names and treaties which today hardly a single student knows. In all of them, the EU worked feverishly on a reform agenda which grew ever more complex, and which produced ever less political union, so that in the end the modest achievement of the establishment of the post of European ombudsman by the European Parliament was celebrated as a victory for European democracy.

The opening of negotiations with Turkey in October 2003 is almost impossible to understand from today’s perspective, and in hindsight can only be explained by American pressure on Europe during the Iraq war. The EU simply wasn’t up to it – France especially, which in May 2005 voted in a referendum against the European constitutional treaty, which made it easier for the Netherlands subsequently to do the same. The German-French relationship, which had already long ceased to be the intimate partnership it had once been, was unable to survive the shock. What was left of the constitutional treaty was cobbled together with some difficulty in 2007 into the Lisbon Treaty, a textual monstrosity and a cardinal political error which from that point on served to thwart the EU’s further progress and capacity for action. It is possible today to look back and recall – with irony or with cynicism, according to personal preference – that at that time Poland was fighting hard for the acceptance of a complex mathematical formula for the weighting of votes in the European Council, and to wonder why it was not possible to acknowledge the absurdity of it all at the time. The Lisbon Treaty emphasised the greater role being played by the European Parliament, yet failed to accord it full parliamentary rights or even to question the grotesque fact that the European Parliament is elected via national candidates’ lists.

From that point on, the power of the European Council grew. It was a turning point. In 2010, the ‘European community method’ was ‘re-coded’ in the mouth of the German Chancellor into the ‘Union method’.7. Political Europe, if it ever existed, is long dead; it died well before the public became aware of the slow, agonising demise of the EU now under way. France has been sulking in a corner for at least ten years now, and this has left Europe to the Germans. But they had a football fairytale to celebrate in 2006, followed by Lena’s victory at the Eurovision Song Contest; then they became the ‘land of the engineers’, and celebrated an ‘export miracle’; and so they politely declined.8 Through all this time, European banks and European businesses were able to make the best of this politically abandoned space and to exploit the inherent weaknesses of the euro and the lack of regulation or public supervision in order to binge on exports and loans.

Where politics could not take hold, economics won out in Europe. This book is not the place for a detailed examination of the many, multi-faceted factors that made up the European malaise, of the slow and painful death of political Europe over the last twenty years. And certainly not the place for a national blame game. In essence, in 2008, a European system without political underpinning was hit very hard by a banking crisis it was politically incapable of dealing with. The Eurozone crisis was never a currency crisis. Throughout the crisis, the euro remained stable with respect to inflation and exchange rates. Countries like Ireland and Spain were not encumbered with debt before the banking crisis. But in political terms, the euro was an orphan currency. The victim of the crisis was already, politically, one of the walking dead; this was why it turned into a European nightmare. It could not be decided politically who should bear the costs of the crisis. Capital was able to flee, but the citizens had to stay put. After the early bold decision to allow Lehman Brothers to go to the wall, nobody subsequently showed similar courage again. Nobody could bring themselves to reassert the primacy of politics and to make those responsible for the crisis – the banks – pay the final price. Instead, a clapped-out and perverted financial system was rescued at taxpayers’ expense, and austerity was imposed to limit the debt. The sell-off of Europe to the financial markets ran its course.

Wherever the political path was blocked for Europe, a relapse into chauvinism remained open. And since it was not possible to point the finger at the failure of European politics and democracy, countries – and with them their citizens – were made the scapegoats. The Greeks drew the shortest straw. From then on, the ECB and ‘the institutions’ governed Europe. The era of European post-democracy had dawned.

The ongoing crisis is the crisis of a non-existent European democracy. It has torn away the veil that lay for so long over the EU’s ambivalent essential character: legal, but not democratic. An absurd institutional system, which from the beginning was described in every EU textbook as sui generis (that is, ‘of its own kind’, unique) as a clever way of obscuring its absurdity – because anything that is sui generis does not need to be explained. Now the EU, the European emperor, is naked. In hindsight, one can only shudder at the way we allowed ourselves to be persuaded for so long by the endless libraries of studies on European multi-level governance that the EU could function indefinitely without any form of direct input legitimacy, without a fully-fledged European parliamentarism, without political accountability. In reality, what we did was to build a Potemkin village and to endow European universities with lots of Jean Monnet Chairs in EU studies so that we could settle this village with the coming generation. But certainly not – perish the thought! – to call into question this sui generis construct.

The neofunctionalist method, according to which – by 1992 and the Maastricht Treaty at the latest – a political union was expected to evolve out of the integrating market, has failed. Its legacy is a constitutional tangle of EU Treaties and overlapping governance structures so complex and multi-layered that even experts cannot understand it. It no longer bears any relation to a functional political system, much less to a system for which one could win popular support. Not only because the blueprint was faulty and incomplete (precisely because it was apolitical); in the meantime, it has also been totally perverted by the course of historical developments.

A market system which is supply-side oriented, not to say neoliberal, has become self-sustaining and has embedded itself in European constitutional law, effectively divorced from any form of democratic legislative process. This has made it more or less irreversible. A triad of Brussels institutions, consisting of the Council, the Parliament and the Commission, primarily concerns itself with its own business, and is not organised in accordance with the principle of the separation of powers. The citizens of Europe are not equal before the law, and are not taxed equally. The principle of the equality of all citizens, a fundamental, constitutive element of every polity, is breached within the EU at the national level. The European Parliament has no right of legislative initiative and does not provide equal voting rights: European citizens do not have equal representation in the voting procedures of the European legislature. Both of these facts represent a full-frontal attack on democracy in Europe: without political and civic equality, there can be no properly functioning parliamentarism. The Commission is simultaneously both executive and guardian of the Treaties; the latter role is normally carried out by a court. A European Council with only indirect legitimation systematically blocks decisions which are in the interests of all European citizens and negotiates in the preferential interests of individual member states, usually the powerful ones – that is, if it is capable of taking decisions at all (cf. the financial transactions tax, or refugees). The Brussels technocracy is overly concerned with small things (the ban on olive oil jugs, light bulbs, or the legendary directive on cucumbers) but cannot manage the big things, for example the registration of refugees at the EU’s external borders and their internal dispersal. Brussels-based officials rather than the parliaments decide on national budgets, and thus on the fates of their citizens. The sitting President of the European Commission suffers the indignity of being accused of tax fraud, and in response the European Parliament doesn’t even institute a commission of inquiry. Powerful lobbies push agreements and regulations through the corridors of Brussels that many European citizens do not want, for example the TTIP free trade agreement, or the so-called ‘Better Regulation’ directive, which will oblige the European Parliament to carry out a cost-benefit analysis for every parliamentary decision and to reverse it if it is found to be too expensive. And when finally the citizens no longer have any idea what is going on, expensive PR agencies are commissioned to create new ‘European narratives’. As if reality could be glossed over with stories. In Aristotle’s typology, the philosophers of ancient Greece would probably have classified today’s EU as a form of despotism.

However, the biggest problem is perhaps not even that the EU is despotic. The EU’s biggest problem is that it cannot even concede that fact in political discourse. For what would happen then? This is the only Europe there is, so it has to be defended. This is the trap in which the political debate over Europe is caught. In Greek, the word for crisis is the same as that for decision. The EU has long outgrown intergovernmentalism, but it cannot bring itself to unify. It cannot make the decision to become a political entity and thus democratic. If you cannot decide to live, you die. That is the true nature of the crisis.

CHAPTER 2

Welcome to European post-democracy

‘We have created a monster.’

Thomas Piketty

As if we hadn’t known. In fact, it was clear from the beginning. The political monster we have created is a system in which the state and the market have been decoupled – by the Maastricht Treaty of 1992. From that point on, decisions on monetary and economic issues were taken at the European level, whereas those on fiscal and social policy continued to be taken at the national level. There was simply no way that could work. Without a political superstructure, the internal market and the euro were doomed to become a dictatorship. A European economic and monetary system was forced on the nation states like a cork being pushed into a bottle, and this has put social policy almost beyond the reach of government. And because this was all embedded within a grand European peace narrative which reached a historic climax with Maastricht in 1992, with the reunified Germany as its emblem, then anyone who dared to criticise it risked having their motives questioned. Who, in the midst of all this, was going to give any thought to the possible economic dangers inherent in a market without a state and a currency without a democracy?

Essentially, the euro shifted the costs of economic policy from business on to the citizens. In the 1970s, due to the extreme volatility of the dollar, European industry – especially in Germany – suffered from severe exchange rate fluctuations within the European internal market. The value of the German Mark was systematically driven upwards and German business lost competitiveness through higher wage costs. This resulted in the demand for fixed exchange rates, and ultimately for a common currency. Economic and monetary union enabled European business (and more particularly once again German business) to avoid the costs created by the constant currency fluctuations within the European markets. The euro was thus a project driven largely by business, one especially dear to the heart of German exporters and banks. For them, exchange rates and transaction costs within the currency union disappeared. It was a gift. European business was given the euro without having to accept European fiscal and social union in return. This was the decisive mistake at the birth of the euro, one which subsequently couldn’t be undone. Crudely speaking, it gave the banks and (exporting) industry licence to milk the Eurozone without having to take on any responsibility for social equality and cohesion within Europe. From this point on, business enjoyed a free rider position in the European internal market that it was later not prepared to relinquish.

Labour and capital were thus de-coupled, and negotiations between them were taken out of the national context. This inevitably led to social upheaval, as ‘capital’ was able to exploit the European institutional structure whereas ‘labour’ was not: labour relations in Europe are not uniform across countries, and labour is much more poorly organised than ‘capital’. ‘Capital’ was given a level playing field, which was a huge advantage; ‘labour’ thereby suffered a huge disadvantage. Hayek 1, Marx 0.9

From contrasting labour relations systems to different rates of corporation tax: Maastricht and the euro created a shoppers’ paradise for business, but for those in paid employment only misery in their respective ‘national containers’.10 The European states undercut each other in a fiscal race to the bottom. Tax dumping by the states was compounded by wage dumping by companies, because collective bargaining at the European level didn’t exist. Basically, competition inside the single market was shifted from business on to the citizens. Whereas business got the freedom to relocate anywhere it wanted on equal or better terms, European citizens had no defence against divergent social standards or tax rates. What was missing was a transnational democratic framework. Because European citizens did not and do not have equality within Europe. The citizens were effectively handed over to the Single Market by their national governments. The European states abandoned their natural role as protectors of their citizens, while at the same time a properly functioning European parliamentary system that might have prevented the worst consequences did not exist.

The most fundamental breach of democracy in the way the EU is currently structured is the fact that the European citizens do not have equal representation in the European Parliament, even though it is there to represent their common interests. This contravenes the principle of electoral equality. Voting does not follow the same rules from Finland to Portugal. One member of parliament does not represent the same number of citizens from Malta to Germany. This blocks the path towards a true European democracy. Germany's Federal Constitutional Court regards the fact that the European Parliament in its current form does not comply with the principle of ‘one person, one vote’ as one of the most important reasons why the European Parliament cannot be considered democratic in the traditional sense. This is why the so-called ‘Responsibility for Integration Act’ (‘Integrationsverantwortungsgesetz’) was introduced in the German Parliament during the ratification process for the Lisbon Treaty, giving the German Bundestag, as the true guarantor of legitimacy, a legal responsibility to monitor the European Parliament.

This is the general pattern for the EU: what is really important cannot be accomplished; it is not possible to implement political and civic equality, a fundamental prerequisite for any polity – and so the EU ties itself in knots, for decades now, in complicated reforms and opaque measures designed to get around and make up for this failure. It thereby creates ever increasing levels of undemocratic entanglements within the system, which are then painted as necessary pragmatism, or as ‘a necessary response to crisis’, and fobbed off on the citizens. However, it is the supposedly sovereign nation states which are preventing the application of the principle of civic and political equality at the European level. Because originally it is not states but citizens who are sovereign,11 yet they are robbed of their legislative rights twice over in the dense jungle of EU governance.

From a structural perspective, parliamentary oversight in the Europe of the EU currently falls between two stools: the national parliaments no longer possess enough legal authority in this regard, while the European Parliament has not yet acquired it. The EU Commission, which initiates European legislation (whether directives or regulations) – usually driven by national governments and their interests – steps into this vacuum. Paradoxically, the national governments then get to vote on the new laws themselves in the European Council. Dieter Grimm,12 a former member of Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court, sets out very clearly how a system has thus evolved in the EU wherein the Executive and the Judiciary have been allowed for decades to operate without proper parliamentary checks. To put it another way: the EU does not comply with Montesquieu’s doctrine of the separation of powers. The Europe of the EU has thus been politically emasculated, and has mutated into an executive and judicial entity in which one thing above all is missing: a place where credible decisions are reached by a political process for which common responsibility can be taken at the European level. Caught inside this strange hybrid between a union of states and a citizens’ union, both national and European democracy are being ground down. The EU is eating its way into the national parliamentary systems. Around 70 percent of all laws are adopted from European legislation – regulations and directives – which for the most part is simply nodded through in the EU committee system. Its fundamental legitimacy is open to question, indeed downright problematic: it is legal but not democratic.