Полная версия

The Pit-Prop Syndicate

Hilliard paused, while Merriman congratulated him on his journey.

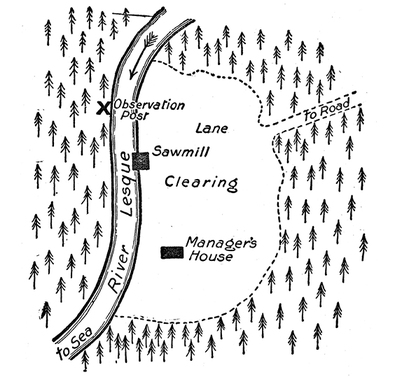

‘Yes, we hadn’t bad luck,’ he resumed. ‘But that really wasn’t what I wanted to tell you about. I had brought a fishing rod and outfit, and on Sunday I took a car and drove out along the Bayonne Road until I came to your bridge over that river—the Lesque I find it is. I told the chap to come back for me at six, and I walked down the river and did a bit of prospecting. The works were shut, and by keeping the mill building between me and the manager’s house, I got close up and had a look round unobserved—at least, I think I was unobserved. Well, I must say the whole business looked genuine. There’s no question those tree cuttings are pit-props, and I couldn’t see a single thing in the slightest degree suspicious.’

‘I told you there could be nothing really wrong,’ Merriman interjected.

‘I know you did, but wait a minute. I got back to the forest again in the shelter of the mill building, and I walked around through the trees and chose a place for what I wanted to do next morning. I had decided to spend the day watching the lorries going to and from the works, and I naturally wished to remain unobserved myself. The wood, as you know, is very open. The trees are thick, but there is very little undergrowth, and it’s nearly impossible to get decent cover. But at last I found a little hollow with a mound between it and the lane and road—just a mere irregularity in the surface like what a tommy would make when he began to dig himself in. I thought I could lie there unobserved, and see what went on with my glass. I have a very good prism monocular—twenty-five diameter magnification, with a splendid definition. From my hollow I could just see through the trees vehicles passing along the main road, but I had a fairly good view of the lane for at least half its length. The view, of course, was broken by the stems, but still I should be able to tell if any games were tried on. I made some innocent looking markings so as to find the place again, and then went back to the river and so to the bridge and my taxi.’

Hilliard paused and drew at his cigar. Merriman did not speak. He was leaning forward, his face showing the interest he felt.

‘Next morning, that was yesterday, I took another taxi and returned to the bridge, again dressed as a fisherman. I had brought some lunch, and I told the man to return for me at seven in the evening. Then I found my hollow, lay down and got out my glass. I was settled there a little before nine o’clock.

‘It was very quiet in the wood. I could hear faintly the noise of the saws at the mill and a few birds were singing, otherwise it was perfectly still. Nothing happened for about half an hour, then the first lorry came. I heard it for some time before I saw it. It passed very slowly along the road from Bordeaux, then turned into the lane and went along it at almost a walking pace. With my glass I could see it distinctly and it had a label plate same as you described, and was No. 6. It was empty. The driver was a young man, clean shaven and fairhaired.

‘A few minutes later a second empty lorry appeared coming from Bordeaux. It was No. 4, and the driver was, I am sure, the man you saw. He was like your description of him at all events. This lorry also passed along the lane towards the works.

‘There was a pause then for an hour or more. About half-past ten the No. 4 lorry with your friend appeared coming along the lane outward bound. It was heavily loaded with firewood and I followed it along, going very slowly and bumping over the inequalities of the lane. When it got to a point about a hundred yards from the road, at, I afterwards found, an S curve which cut off the view in both directions, it stopped and the driver got down. I need not tell you that I watched him carefully and, Merriman, what do you think I saw him do?’

‘Change the number plate?’ suggested Merriman with a smile.

‘Change the number plate!’ repeated Hilliard. ‘As I’m alive, that’s exactly what he did. First on one side and then on the other. He changed the 4 to a 1. He took the 1 plates out of his pocket and put the 4 plates back instead, and the whole thing just took a couple of seconds, as if the plates slipped in and out of a holder. Then he hopped up into his place again and started off. What do you think of that?’

‘Goodness only knows,’ Merriman returned slowly. ‘An extraordinary business.’

‘Isn’t it? Well, that lorry went on out of sight. I waited there until after six, and four more passed. About eleven o’clock No. 6 with the clean shaven driver passed out, loaded, so far as I could see, with firewood. That was the one that passed in empty at nine. Then there was a pause until half-past two, when your friend returned with his lorry. It was empty this time, and it was still No. 1. But I’m blessed, Merriman, if he didn’t stop at the same place and change the number back to 4!’

‘Lord!’ said Merriman tersely, now almost as much interested as his friend.

‘It only took a couple of seconds, and then the machine lumbered on towards the mill. I was pretty excited, I can tell you, but I decided to sit tight and await developments. The next thing was the return of No. 6 lorry and the clean shaven driver. You remember it had started out loaded at about eleven. It came back empty shortly after the other, say about quarter to three. It didn’t stop and there was no change made with its number. Then there was another pause. At half-past three your friend came out again with another load. This time he was driving No 1, and I waited to see him stop and change it. But he didn’t do either. Sailed away with the number remaining 1. Queer, isn’t it?’

Merriman nodded and Hilliard resumed.

‘I stayed where I was, still watching, but I saw no more lorries. But I saw Miss Coburn pass about ten minutes later—at least I presume it was Miss Coburn. She was dressed in brown, and was walking smartly along the lane towards the road. In about an hour she passed back. Then about five minutes past five some workmen went by—evidently the day ends at five. I waited until the coast was clear, then went down to the lane and had a look round where the lorry had stopped, and saw it was a double bend and therefore the most hidden point. I walked back through the wood to the bridge, picked up my taxi and got back here about half-past seven.’

There was silence for some minutes after Hilliard ceased speaking, then Merriman asked:

‘How long did you say those lorries were away unloading?’

‘About four hours.’

‘That would have given them time to unload in Bordeaux?’

‘Yes; an hour and a half in, the same out, and an hour in the city. Yes, that part of it is evidently right enough.’

Again silence reigned, and again Merriman broke it with a question.

‘You have no theory yourself?’

‘Absolutely none.’

‘Do you think that driver mightn’t have some private game of his own on—be somehow doing the syndicate?’

‘What about your own argument?’ answered Hilliard. ‘Is it likely Miss Coburn would join the driver in anything shady? Remember, your impression was that she knew.’

Merriman nodded.

‘That’s right,’ he agreed, continuing slowly: ‘Supposing for a moment it was smuggling. How would that help you to explain this affair?’

‘It wouldn’t. I can get no light anywhere.’

The two men smoked silently, each busy with his thoughts. A certain aspect of the matter which had always lain subconsciously in Merriman’s mind was gradually taking concrete form. It had not assumed much importance when the two friends were first discussing their trip, but now that they were actually at grips with the affair it was becoming more obtrusive, and Merriman felt it must be faced. He therefore spoke again.

‘You know, old man, there’s one thing I’m not quite clear about. This affair that you’ve discovered is extraordinarily interesting and all that, but I’m hanged if I can see what business of ours it is.’

Hilliard nodded swiftly.

‘I know,’ he answered quickly. ‘The same thing has been bothering me. I felt really mean yesterday when that girl came by, as if I were spying on her, you know. I wouldn’t care to do it again. But I want to go on to this place and see into the thing farther, and so do you.’

‘I don’t know that I do specially.’

‘We both do,’ Hilliard reiterated firmly, ‘and we’re both justified. See here. Take my case first. I’m in the Customs Department, and it is part of my job to investigate suspicious import trades. Am I not justified in trying to find out if smuggling is going on? Of course I am. Besides, Merriman, I can’t pretend not to know that if I brought such a thing to light I should be a made man. Mind you, we’re not out to do these people any harm, only to make sure they’re not harming us. Isn’t that sound?’

‘That may be all right for you, but I can’t see that the affair is any business of mine.’

‘I think it is.’ Hilliard spoke very quietly. ‘I think it’s your business and mine—the business of any decent man. There’s a chance that Miss Coburn may be in danger. We should make sure.’

Merriman sat up sharply.

‘In Heaven’s name, what do you men, Hilliard?’ he cried fiercely. ‘What possible danger could she be in?’

‘Well, suppose there is something wrong—only suppose, I say,’ as the other shook his head impatiently. ‘If there is, it’ll be on a big scale, and therefore the men who run it won’t be over squeamish. Again, if there’s anything, Miss Coburn knows about it. Oh, yes, she does,’ he repeated as Merriman would have dissented, ‘there is your own evidence. But if she knows about some large, shady undertaking, she undoubtedly may be in both difficulty and danger. At all events, as long as the chance exists it’s up to us to make sure.’

Merriman rose to his feet and began to pace up and down, his head bent and a frown on his face. Hilliard took no notice of him and presently he came back and sat down again.

‘You may be right,’ he said. ‘I’ll go with you to find that out, and that only. But I’ll not do any spying.’

Hilliard was satisfied with his diplomacy. ‘I quite see your point,’ he said smoothly, ‘and I confess I think you are right. We’ll go and take a look round, and if we find things are all right we’ll come away again, and there’s no harm done. That agreed?’

Merriman nodded.

‘What’s the programme then?’ he asked.

‘I think tomorrow we should take the boat round to the Lesque. It’s a good long run and we mustn’t be late getting away. Would five be too early for you?’

‘Five? No, I don’t mind if we start now.’

‘The tide begins to ebb at four. By five we shall get the best of its run. We should be out of the river by nine, and in the Lesque by four in the afternoon. Though that mill is only seventeen miles from here as the crow flies, it’s a frightful long way round by sea, most of 130 miles, I should say.’ Hilliard looked at his watch. ‘Eleven o’clock. Well, what about going back to the Swallow and turning in?’

They left the Jardin, and, sauntering slowly through the well-lighted streets, reached the launch and went on board.

CHAPTER IV

A COMMERCIAL PROPOSITION

MERRIMAN was aroused next morning by the feeling rather than the sound of stealthy movements going on not far away. He had not speedily slept after turning in. The novelty of his position, as well as the cramped and somewhat knobby bed made by the locker, and the smell of oils, had made him restless. But most of all the conversation he had had with Hilliard had banished sleep, and he had lain thinking over the adventure to which they had committed themselves, and listening to the little murmurings and gurglings of the water running past the piles and lapping on the woodwork beside his head. The launch kept slightly on the move, swinging a little backwards and forwards in the current as it alternately tightened and slackened its mooring ropes, and occasionally quivering gently as it touched the wharf. Three separate times Merriman had heard the hour chimed by the city clocks, and then at last a delightful drowsiness had crept over him, and consciousness had gradually slipped away. But immediately this shuffling had begun, and with a feeling of injury he roused himself to learn the cause. Opening his eyes he found the cabin was full of light from the dancing reflections of sunlit waves on the ceiling, and that Hilliard, dressing on the opposite locker, was the author of the sounds which had disturbed him.

‘Good!’ cried the latter cheerily. ‘You’re awake? Quarter to five and a fine day.’

‘Couldn’t be,’ Merriman returned, stretching himself luxuriously. ‘I heard it strike two not ten seconds ago.’

Hilliard laughed.

‘Well, it’s time we were under way anyhow,’ he declared. ‘Tide’s running out this hour. We’ll get a fine lift down to the sea.’

Merriman got up and peeped out of the porthole above his locker.

‘I suppose you tub over the side?’ he inquired. ‘Lord, what sunlight!’

‘Rather. But I vote we wait an hour or so until we’re clear of the town. I fancy the water will be more inviting lower down. We could stop and have a swim, and then we should be ready for breakfast.’

‘Right-o. You get way on her, or whatever you do, and I shall have a shot at clearing up some of the mess you keep here.’

Hilliard left the cabin, and presently a racketing noise and vibration announced that the engines had been started. This presently subsided into a not unpleasing hum, after which a hail came from forward.

‘Lend a hand to cast off, like a stout fellow.’

Merriman hurriedly completed his dressing and went on deck, stopping in spite of himself to look around before attending to the ropes. The sun was low down over the opposite bank, and transformed the whole river down to the railway bridge into a sheet of blinding light. Only the southern end of the great structure was visible stretching out of the radiance, as well as the houses on the western bank, but these showed out with incredible sharpness in high lights and dark shadows. From where they were lying they could not see the great curve of the quays, and the town in spite of the brilliancy of the atmosphere looked drab and unattractive.

‘Going to be hot,’ Hilliard remarked. ‘The bow first, if you don’t mind.’

He started the screw, and kept the launch alongside the wharf while Merriman cast off first the bow and then the stern ropes. Then, steering out towards the middle of the river, he swung round and they began to slip rapidly down-stream with the current.

After passing beneath the huge mass of the railway bridge they got a better view of the city, its rather unimposing buildings clustering on the great curve of the river to the left, and with the fine stone bridge over which they had driven on the previous evening stretching across from bank to bank in front of them. Slipping through one of its seventeen arches, they passed the long lines of quays with their attendant shipping, until gradually the houses got thinner and they reached the country beyond.

About a dozen miles below the town Hilliard shut off the engines, and when the launch had come to rest on the swift current they had a glorious dip—in turn. Then the odour of hot ham mingled in the cabin with those of paraffin and burnt petrol, and they had an even more glorious breakfast. Finally the engines were restarted, and they pressed steadily down the ever-widening estuary.

About nine they got their first glimpse of the sea horizon, and, shortly after, a slight heave gave Merriman a foretaste of what he must soon expect. The sea was like a mill pond, but as they came out from behind the Pointe de Grave they began to feel the effect of the long, slow ocean swell. As soon as he dared Hilliard turned southwards along the coast. This brought the swells abeam, but so large were they in relation to the launch that she hardly rolled, but was raised and lowered bodily on an almost even keel. Though Merriman was not actually ill, he was acutely unhappy and experienced a thrill of thanksgiving when, about five o’clock, they swung round east and entered the estuary of the Lesque.

‘Must go slowly here,’ Hilliard explained, as the banks began to draw together. ‘There’s no sailing chart of this river, and we shall have to feel our way up.’

For some two miles they passed through a belt of sand-dunes, great yellow hillocks shaded with dark green where grasses had seized a precarious foothold. Behind these the country grew flatter, and small, blighted looking shrubs began to appear, all leaning eastwards in witness to the devastating winds which blew in from the sea. Farther on these gave place to stunted trees, and by the time they had gone ten or twelve miles they were in the pine forest. Presently they passed under a girder bridge, carrying the railway from Bordeaux to Bayonne and the south.

‘We can’t be far from the mill now,’ said Hilliard a little later. ‘I reckoned it must be about three miles above the railway.’

They were creeping up very slowly against the current. The engines, running easily, were making only a subdued murmur inaudible at any considerable distance. The stream here was narrow, not more than about a hundred yards across, and the tall, straight stemmed pines grew down to the water’s edge on either side. Already, though it was only seven o’clock, it was growing dusk in the narrow channel, and Hilliard was beginning to consider the question of moorings for the night.

‘We’ll go round that next bend,’ he decided, ‘and look for a place to anchor.’

Some five minutes later they steered close in against a rapidly shelving bit of bank, and silently lowered the anchor some twenty feet from the margin.

‘Jove! I’m glad to have that anchor down,’ Hilliard remarked, stretching himself. ‘Here’s eight o’clock, and we’ve been at it since five this morning. Let’s have supper and a pipe, and then we’ll discuss our plans.’

‘And what are your plans?’ Merriman asked, when an hour later they were lying on their lockers, Hilliard with his pipe and Merriman with a cigar.

‘Tomorrow I thought of going up in the collapsible boat until I came to the works, then landing on the other bank and watching what goes on at the mill. I thought of taking my glass and keeping cover myself. After what you said last night you probably won’t care to come, and I was going to suggest that if you cared to fish you would find everything you wanted in that forward locker. In the evening we could meet here and I would tell you if I saw anything interesting.’

Merriman took his cigar from his lips and sat up on the locker.

‘Look here, old man,’ he said, ‘I’m sorry I was a bit ratty last night. I don’t know what came over me. I’ve been thinking of what you said, and I agree that your view is the right one. I’ve decided that if you’ll have me, I’m in this thing until we’re both satisfied there’s nothing going to hurt either Miss Coburn or our own country.’

Hilliard sprang to his feet and held out his hand.

‘Cheers!’ he cried. ‘I’m jolly glad you feel that way. That’s all I want to do too. But I can’t pretend my motives are altogether disinterested. Just think of the kudos for us both if there should be something.’

‘I shouldn’t build too much on it.’

‘I’m not, but there is always the possibility.’

Next morning the two friends got out the collapsible boat, locked up the launch, and paddling gently up the river until the galvanised gable of the Coburn’s house came in sight through the trees, went ashore on the opposite bank. The boat they took to pieces and hid under a fallen trunk, then, screened by the trees, they continued their way on foot.

It was still not much after seven, another exquisitely clear morning giving promise of more heat. The wood was silent though there was a faint stir of life all around them, the hum of invisible insects, the distant singing of birds as well as the murmur of the flowing water. Their footsteps fell soft on the carpet of scant grass and decaying pine needles. There seemed a hush over everything, as if they were wandering amid the pillars of some vast cathedral with, instead of incense, the aromatic smell of the pines in their nostrils. They walked on, repressing the desire to step on tiptoe, until through the trees they could see across the river the galvanised iron of the shed.

A little bit higher up-stream the clearing of the trees had allowed some stunted shrubs to cluster on the river bank. These appearing to offer good cover, the two men crawled forward and took up a position in their shelter.

The bank they were on was at that point slightly higher than that on the opposite side, giving them an excellent view of the wharf and mill as well as of the clearing generally. The ground, as has already been stated, was in the shape of a D, the river bounding the straight side. About half-way up this straight side was the mill, and about half-way between it and the top were the shrubs behind which the watchers were seated. At the opposite side of the mill from the shrubs, at the bottom of the D pillar, the Coburn’s house stood on a little knoll.

‘Jolly good observation post, this,’ Hilliard remarked as he stretched himself at ease and laid his glass on the ground beside him. ‘They’ll not do much that we shall miss from here.’

‘There doesn’t seem to be much to miss at present,’ Merriman answered, looking idly over the deserted space.

About a quarter to eight a man appeared where the lane from the road debouched into the clearing. He walked towards the shed, disappearing presently behind it. Almost immediately blue smoke began issuing from the metal chimney in the shed roof. It was evident he had come before the others to get up steam.

In about half an hour those others arrived, about fifteen men in all, a rough-looking lot in labourers’ kit. They also vanished behind the shed, but most of them reappeared almost immediately, laden with tools, and, separating into groups, moved off to the edge of the clearing. Soon work was in full swing. Trees were being cut down by one gang, the branches lopped off fallen trunks by another, while a third was loading up and running the stripped stems along a Decauville railway to the shed. Almost incessantly the thin screech of the saws rose penetratingly above the sounds of hacking and chopping and the calls of men.

‘There doesn’t seem to be much wrong there,’ Merriman said when they had surveyed the scene for nearly an hour.

‘No,’ Hilliard agreed, ‘and there didn’t seem to be much wrong when I inspected the place on Sunday. But there can’t be anything obviously wrong. If there is anything, in the nature of things it won’t be easy to find.’

About nine o’clock Mr Coburn, dressed in gray flannel, emerged from his house and crossed the grass to the mill. He remained there for a few minutes, then they saw him walking to the workers at the forest edge. He spent some moments with each gang, afterwards returning to his house.

For nearly an hour things went on as before, and then Mr Coburn reappeared at his hall door, this time accompanied by his daughter. Both were dressed extraordinarily well for such a backwater of civilisation, he with a gray Homburg hat and gloves, she as before in brown, but in a well-cut coat and skirt and a smart toque and motoring veil. Both were carrying dust coats. Mr Coburn drew the door to, and they walked towards the mill and were lost to sight behind it. Some minutes passed, and between the screaming of the saws the sound of a motor engine became audible. After a further delay a Ford car came out from behind the shed and moved slowly over the uneven sward towards the lane. In the car were Mr and Miss Coburn and a chauffeur.

Hilliard had been following every motion through his glass, and he now thrust the instrument into his companion’s hand, crying softly:

‘Look, Merriman. Is that the lorry driver you saw?’ Merriman focused the glass on the chauffeur and recognised him instantly. It was the same dark, aquiline featured man who had stared at him so resentfully on the occasion of his first visit to the mill, some two months earlier.