Полная версия

The Ponson Case

An hour later the two constables who had been sent to search the lower reaches of the river arrived at the police station. They had found the missing oars, and had taken them to Luce Manor, where they had been identified by Smith, the boatman. They had, it appeared, gone ashore close beside each other nearly a mile below the falls, and two points about the affair had interested the men. First, the oars had been washed up on the left bank, while the other things had been deposited on the right, and second, while all the latter were torn and damaged by the rocks, neither oar was injured or even marked.

‘What do you make of that, Cowan?’ the sergeant asked when these facts had been put before him.

‘Well, I’ll tell you what the boatman says, and it seems right enough. You know that there road bridge above the falls? There’s two arches in it. Well, Smith says he’ll lay ten bob the boat went through one arch and the oars the other. That would look right enough to me too, because the right side is more shallow and more rocky than the other, and more likely for to break anything up. The left side is the main channel, as you might say, and the oars might get down it without damage. At least, that’s what Smith says, and it looks like enough to me too.’

‘H’m,’ the sergeant mused, ‘seems reasonable.’ The sergeant knew more about sea currents than river. He had been brought up on the coast, and he had learnt that tidal currents having the same set will deposit objects at or about the same place. It seemed to him likely that a similar rule would apply to rivers. The body, boat, rudder, and bottom boards had all gone ashore at one place. The oars also were found not far apart, but they were a long way from the other things. What more likely than the boatman’s suggestion that the two lots of objects had become sufficiently divided in the upper reach to pass through different arches of the bridge? This would separate them completely enough to account for the positions in which they were found. Yes, it certainly seemed reasonable.

And then another idea struck him, and he slapped his thigh.

‘By Jehosaphat, Cowan!’ he cried, ‘that’s just what’s happened, and it explains the only thing we didn’t know about the whole affair. Those oars went through the other arch right enough. And why? Why, because Sir William had lost them coming down the river. That’s why he was lost himself. I’ll lay you anything those oars got overboard, and he couldn’t find them in the dark.’

To the sergeant, who was not without imagination, there came the dim vision of an old, grey-haired man, adrift, alone and at night, in a light skiff on the swirling flood—borne silently and resistlessly onward, while he struggled desperately in the shrouding darkness to recover the oars which had slipped from his grasp, and which were floating somewhere close by. He could almost see the man’s frantic, unavailing efforts to reach the bank, almost hear his despairing cries rising above the rush of the waters and the roar of the fall, as more and more swiftly he was swept on to his doom. Almost he could visualise the tossing, spinning boat disappear under the bridge, emerge, hang poised as if breathless for the fraction of a second above the fall, then with an unhurried, remorseless swoop, plunge into the boiling cauldron below.… A horrible fantasy truly, but to the sergeant it seemed a picture of the actual happening.

But why, he wondered, had both the oars taken the other arch? It would have been easier to explain the loss of one. With an unskilful boatman such a thing not unfrequently occurred. But to lose both involved some special cause. Possibly, he thought, Sir William had had some sudden start, had moved sharply, almost capsizing the boat, and in making an involuntary effort to right it had let go with both hands.

He was still puzzling over the problem when a note was handed him which, when he had read it, banished the matter of the oars from his mind, and turned his thoughts into a fresh direction. It ran:

Luce Manor, Thursday.—Please come out here at once. An unfortunate development has arisen.—WALTER AMES.

Without loss of time the sergeant took his bicycle and rode out the two miles to Luce Manor. Dr Ames was waiting impatiently, and drew the officer aside.

‘Look here, sergeant,’ he said. ‘I’m not very happy about this business. I want a post-mortem.’

‘A post-mortem sir?’ the other repeated in astonishment. ‘Why, sir, is there anything fresh turned up, or what has happened?’

‘Nothing has happened, but’—the doctor hesitated—‘the fact is I’m not certain of the cause of death.’

The sergeant stared.

‘But is there any doubt, sir—you’ll excuse me, I hope—is there any doubt that he was drowned?’

‘That’s just what there is—a doubt and no more. A post-mortem will set it at rest.’

The sergeant hesitated.

‘Of course, sir,’ he said slowly, ‘if you say that it ends the matter. But it’ll be a nasty shock for Mr Austin, sir.’

‘I can’t help that. See here,’ the doctor went on confidentially, ‘some of the obvious signs of drowning are missing, and he has had a blow on the back of the head that looks as if it might have killed him. I want to make sure which it was.’

‘But might he not have got that blow against a rock, sir?’

‘He might, but I’m not sure. But we’re only wasting time. To put the matter in a nutshell, I won’t give a certificate unless there is a post-mortem, and if one is not arranged now, it will be after my evidence at the inquest.’

‘Please don’t think, sir, I was in any way questioning your decision,’ the sergeant hastened to reply. ‘But I think I should first communicate with the chief constable. You see, sir, in the case of so prominent a family—’

‘You do what you think best about that, but if you take my advice you’ll ask the Scotland Yard people to send down one of their doctors to act with me.’

‘Bless me, sir! Is it as serious as that?’

‘Of course it’s serious,’ rapped out the doctor. ‘Sir William may have been drowned, in which case it’s all right; or he may not, in which case it’s all wrong—for somebody.’

The sergeant’s manner changed.

‘I’ll go immediately, sir, and phone the chief constable, and then, if he approves, Scotland Yard. Where will you be, sir?

‘I have my work to attend to; I’m going home. You’ll find me there any time during the evening. And look here, sergeant. I’d rather you said nothing about this. There may be nothing at all in it.’

‘Trust me, sir,’ and with a salute the officer withdrew.

He rode rapidly back to Halford, and once again calling up the chief constable, repeated what Dr Ames had said.

The two men discussed the matter at some length, and it was at last decided that the chief constable should ring up the Yard and ask the opinion of the Authorities about sending down a doctor. In a short time there was a reply. Dr Wilgar and Inspector Tanner were motoring down, and would be at Luce Manor about eight o’clock. The sergeant went round to tell Dr Ames, and it was arranged that the latter should meet the London men there. In the meantime the sergeant was to see Austin Ponson, and break the disagreeable news to him.

This programme was carried out, and shortly after ten o’clock five men met at the police station at Halford. There were the medical men, Inspector Tanner, the sergeant, and Chief Constable Soames, who had motored over.

‘Well, gentlemen,’ said the latter, when the preliminary greetings were past, ‘we are met here under unusual and tragic circumstances, which may easily become more serious still.’ He turned to the doctors. ‘You have completed the post-mortem, I understand?’

‘We have,’ replied Dr Wilgar.

‘And are you in agreement as to your conclusions?’

‘Completely.’

‘Perhaps then you would tell us what they are?’

Wilgar bowed to Dr Ames, and the latter replied:

‘The first moment I glanced at the body the thought occurred to me that it had not exactly the appearance of a drowned man. But at that time I did not seriously doubt that death had so occurred. When, however, I came to make a more careful examination, the uncertainty again arose in my mind. There was none of the discolouration usual in such cases, and the wounds on the side of the face did not look as if they had been inflicted before death. But, as a result of the long continued washing they had had, I could not be certain of this. When in addition I discovered a bruise on the back of the head which might easily have caused death, I felt I would not be justified in giving a certificate without further examination.’

The chief constable bowed and Dr Wilgar took up the story.

‘When I saw the corpse I quite agreed with my colleague’s views, and we decided the post-mortem must be carried out. As a result of it we find the man was not drowned.’

His hearers stared at him, but without interrupting.

‘There was no water in the lungs or stomach,’ went on Dr Wilgar. ‘The wounds on the face occurred after death, and were doubtless caused by the boulders in the river, but the cause of death was undoubtedly the blow on the back of the head to which my colleague has referred.’

‘You amaze me, gentlemen,’ the chief constable remarked, and a similar emotion showed on the sergeant’s expressive face. Inspector Tanner, a fair haired, blue eyed, clean-shaven man of about forty, merely looked keenly interested.

‘Do I understand you to say that the late Sir William was killed before falling into the river?’ went on Mr Soames.

‘There is no doubt of it.’

‘That means, I take it, that he was flung out of the boat in such a way that the back of his head struck a rock, killing him before he dropped into the stream?’

‘We do not think so, sir,’ Dr Wilgar answered. ‘In that case he would certainly have swallowed water. Besides, the blow was struck square on with a blunt, smooth-surfaced implement. The skin was not cut as a boulder would have cut it. No, we regret to say so, but the only hypothesis which seems to meet the facts is that Sir William was deliberately murdered.’

‘Good gracious, gentlemen, you don’t say so!’ The chief constable seemed shocked, while the sergeant actually gasped.

‘I am afraid, and Dr Ames agrees with me, that there is no alternative. The blow on the back of the head was struck while Sir William was alive, and it could not have been self inflicted. It would have been sufficient to kill him. The other injuries occurred after death, and it is certain he was not drowned. There is no escape from the conclusion that I have stated. On the contrary, there is every reason to believe a deliberate and carefully thought out crime has been committed. Though it is hardly our province, it seemed to us the whole episode of the boat and the river was merely an attempt to hide the true facts by providing the suggestion of an accident. And I may perhaps be permitted to say that had a less observant and conscientious man than my colleague been called in, the ruse might easily have succeeded.’

‘You amaze me, sir,’ exclaimed Mr Soames. ‘A terrible business! I knew the poor fellow well. I met him in Gateshead before he moved to these parts, and we have been good friends ever since. A sterling, good fellow as ever breathed! I cannot imagine anyone wishing him harm. However, it shows how little we know’…He turned to Inspector Tanner. ‘I presume, Inspector, you came here prepared to take over the case?’

‘Certainly, sir; I was sent for that purpose.’

‘Well, the sooner you get to work the better. And now about the inquest. With the medical evidence there can be but one verdict.’

‘I think, sir,’ observed Tanner, ‘that with your approval it might be wiser to hold that evidence back. It might put some one on his guard, who would otherwise give himself away. I should suggest formal evidence of identification, and an adjournment.’

‘Very possibly you are right, Inspector. What reason would you give for that procedure?’

‘I would say, sir, that it is desirable on technical grounds that some motive for Sir William’s taking out the boat should be discovered, and that the inquest is being adjourned to enable inquiries on this point to be made.’

‘Very well. I shall see the coroner and arrange it with him. It is not of course necessary for me to remind you of the importance of secrecy,’ and with a bow Chief Constable Soames took his leave, and the meeting broke up.

‘Come along round and have some supper at the George,’ Inspector Tanner invited the sergeant. ‘I’ve got a private room, and I want a talk over this business.’

The sergeant, flushed with the honour, and delighting in his feeling of importance, accepted, and the two went out together.

An hour later they lit up their pipes, and Tanner listened while the sergeant told him in detail all he knew of the affair. Then the Inspector unrolled a large-scale map he had brought, and spread it on the table.

‘I want,’ he said, ‘to learn my way about. Just come and point out the places on the map. Here,’ he pointed as he spoke, ‘is Halford, a place of, I suppose, 3000 inhabitants.’ The sergeant nodded and the other resumed. ‘This road running through the town from north to south is the main road from Bedford to London. Now, let’s see. Going towards London it crosses the Cranshaw River at the London side of Halford, and for about a mile both run nearly parallel. Then at the end of the mile, what’s this? A lane leading from the road to the river?’

‘Yes, that’s what we call the Old Ferry. It’s a grass-grown lane through trees, and there’s a broken-down pier at the end of it.’

‘H’m. Then the river bears away towards the south-east; while the road continues almost due south. Luce Manor is here in this vee between them?’

‘Yes, that’s it, sir.’

‘I see. Then at the end of Luce Manor, a cross road runs from the Bedford–London road eastwards, crossing the river just above the falls and leading to Hitchin?’

‘Yes, sir. That’s right.’

‘So that the Luce Manor grounds make a triangle bounded by the main London road, the cross road to Hitchin and the river.’

The Inspector smoked in silence for some minutes. Then, rolling up the map, he went on:

‘Now I want to learn my dates, and also what weather you have been having. This is Thursday night, and it was, therefore, Wednesday night or early this morning the affair happened. Now what about the weather?’

‘We’ve had a lot of rain lately. It was wet up to last Monday. In the afternoon it cleared up, and it has been fine since—that is, here. But farther up the country there has been a lot of thunder and heavy rain. That has left the river full for this time of year.’

‘Wet up till Monday afternoon, and fine since, I see. Well, sergeant, I think that’s about all we can do tonight. By the way, could you lend me a bicycle for the morning?’

‘Certainly, I’ll leave it round now,’ and with an exchange of good-nights the men separated.

CHAPTER III

HOAXED?

AS soon as it was light next morning Inspector Tanner let himself out of the hotel, and taking the sergeant’s bicycle, rode out along the London Road. It was again a perfect morning, everything giving promise of a spell of settled weather. The dew lay thick on the ground, sparkling in the rays of the rising sun, which cast long, thin shadows across the road. Not a cloud was in the sky, and though a few traces of mist still lingered on the river, they were rapidly disappearing in the growing heat. From the trees came the ceaseless twittering of birds, while from some unseen height a lark poured down its glorious song. The roads had dried up after the recent rains, but were not yet dusty, and as the Inspector pedalled along he congratulated himself on the pleasant respite he was likely to have from London in July.

He crossed the Cranshaw River, and gradually diverging from it, rose briskly through the smiling, well-wooded country. About a mile from the town a grass-grown lane branched off to the left, leading, he presumed, back to the river at the Old Ferry. From it began the stone wall which bounded the Luce Manor grounds, and he passed first the small door at the end of the footpath from the house, and then the main entrance. A little farther, some two miles from the town, he reached the cross roads and, turning to the left and still skirting the Manor lands, arrived after a few minutes at the two-arched bridge which crossed the Cranshaw immediately above the falls. Here he hid the bicycle among some bushes, then stepping on to the bridge, he looked around.

The river had greatly fallen, as he could see from the high water mark along the banks. But even now it was running fast, and swirled and eddied as it raced through the archways beneath. Below the falls the two distinct channels were visible, and Tanner could understand how objects passing through the right arch would almost inevitably get among the boulders and be smashed up, while those carried through the other might slip downstream uninjured.

In the opposite direction the river curved away between thinly-wooded banks, and on those banks the Inspector decided his work must begin. From the medical evidence it had seemed clear to him that Sir William Ponson had first been murdered, the body afterwards being placed in the boat. With the ground in the soft condition produced by the recent rains, this could hardly have been done without leaving traces. He must therefore search for those traces in the hope of finding with them some clue to the murderer’s identity.

Not far from the bridge there was a gate in the Luce Manor wall, leading from the road into the plantation of small trees which fringed the river. He passed through, and getting down near the water’s edge, began to walk upstream, scrutinising the ground for footprints. As he expected, most of the bank was still soft from the rain, but where he came to hard or grassy portions or where the rock out-cropped, he made little detours till he reached more plastic ground beyond. It was during one of these deviations, some quarter of a mile from the bridge, that he made his first discovery.

At this point a small stream entered the river, and the ground for some distance on each side had been trampled over by cattle coming to drink. The brook, which was not more than a couple of yards wide by a few inches deep, was crossed by a line of rough stepping-stones. The Inspector, looking about, saw that several persons had recently passed over. Their tracks converged like a fan at each end of the stones. Here, he thought, is where Austin Ponson and the butler, valet and boatman walked when searching for the body.

But Tanner was a painstaking and conscientious man. He never took probabilities for granted and, therefore, at the approaches to the stepping-stones, he set himself to check his theory by separating out the four prints for future identification. It gave him some trouble, but he presently found himself rewarded. Instead of there being four different prints, there were five. Four men had walked together down the river; the fifth had crossed slightly diagonally to the others, and had gone upstream. In all cases where the steps of this fifth man coincided with others the former were the lower, showing that their owner had passed up before the others came down. He had worn boots with nailed soles, and his steps were smaller and closer together than any of the others. Tanner deduced a small-sized man of the working classes.

He was about to move on, when, looking up the little tributary, he saw another line of steps crossing it some thirty yards above the stones. These were heading downstream, and the owner had evidently not troubled to diverge to the stones, but had walked right through the water. The soil at the place was spongy, and the tracks were not clear, but Tanner, by following them back, was able to identify them as those of this same fifth man.

The Inspector at first was somewhat puzzled by the neglect of the stepping-stones. Then it occurred to him that one of two things would account for it. Either the downward journey had been made at night when the unknown could not see the stones, or he had been too perturbed or excited to consider where he was going. And Tanner could not help recognising that anyone hastening from the scene of the murder would in all probability show traces of just such agitation.

He continued his search of the bank, seeing no traces of an approach to the river, but finding here and there prints of the four men going downstream, and of the fifth leading in both directions.

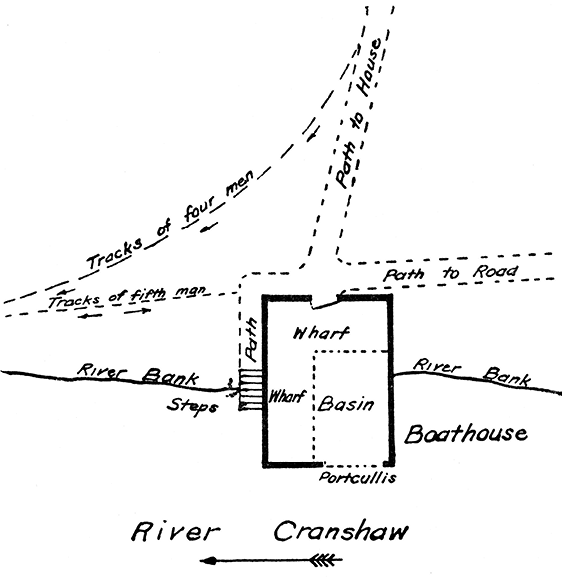

About a hundred yards before he reached the boathouse a paling went up at right angles to the river, separating the rough, uncared for bank along which he had passed from the well-kept lawn he was approaching. The grass on this latter was cut short, and looking up under the fine oaks and beeches studded about, he could see the façade of the house. A gravel path connected the two buildings, leading from the Dutch garden in front of the terrace straight down to the door of the boathouse. From the latter point another path branched off at right angles to the first, running upstream along the river bank. This, Tanner remembered from his examination of the map, afterwards curved round to the left, and joined the narrow walk from the house at the road gate. A third short path ran round the boathouse, and terminated in a flight of broad landing steps, leading down into the river.

A careful search of the ground near the boathouse revealed occasional impressions on the closely cut sward. The Inspector spent over an hour moving from point to point, and was at last satisfied as to what had taken place. The four men whom he had assumed were Austin and the servants, had evidently come down the path from the direction of the house. They had turned to the right before reaching the boathouse, thus approaching the river diagonally, and had crossed the paling bounding the lawn close to the water’s edge. These men had walked together and the tracks were exactly in accordance with the statement of their movements they had made to the sergeant.

The fifth man had crossed the paling almost at the same place as the others—it was the obviously suitable place—but instead of turning up towards the house, his steps led direct to the boathouse! Another line of the same steps led back from the boathouse to the fence—in neither case continuously, but here and there, where the grass was thin. And at two points along these tracks the Inspector gave a chuckle of satisfaction. At one there was a perfect impression of part of the right sole, and at another of the remainder and the heel. Tanner decided he must take plaster casts of these prints before they became blurred.

Passing the boathouse—he felt that marks in it, if any, would keep—he continued his careful search of the bank above flood level. Very painstaking and thorough he was as he gradually worked his way up, but no further traces could he find. At last after a good hour’s work he reached the Old Ferry. Here the track approaching the ruined pier was hard; and he recognised that, shut in as it was by trees, it would have made an ideal place for disposing of the body. He thought he need hardly expect traces above this, but, as he wished to cross the river, and he could do so no nearer than the London road bridge at Halford, he continued along the bank, still searching. Then, reaching the bridge, he crossed and worked in the same way down the left bank till he reached the other bridge at the Cranshaw Falls. When the work was completed, he felt positive the body could only have been set adrift at either the boathouse or the Old Ferry.

It was now eleven o’clock, and he had been at it for over five hours. Taking the bicycle, he rode back into Halford, where he had a hurried meal. Then he left again to attend the inquest at Luce Manor.

A long, narrow room, with oak-panelled walls, and three deep windows, had been set aside for the occasion. Round the table, which ran down the centre, sat the jury, looking self-conscious and important. At the head was the Coroner, and near him, but a little back from the table, were Austin and Cosgrove Ponson, Dr Ames, the butler, valet, boatman, sergeant, and a few other persons. As Tanner entered and slipped quietly to a seat, the Coroner was just rising to open the proceedings.