Полная версия

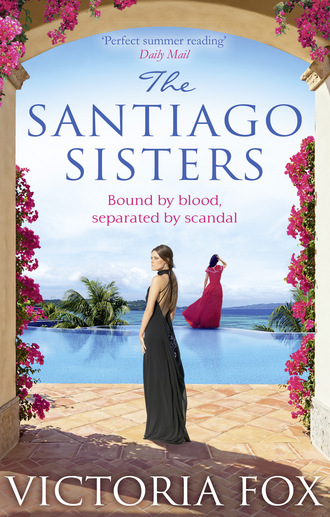

The Santiago Sisters

Julia closed her eyes, as if with the effort of concealing a truth too thrilling to keep at simmering point. ‘Simone wishes to offer one of you girls a special vacation,’ she said, ‘as a way of thanks. To stay with her in London over the English summer.’

Calida didn’t know why her mother bothered to make it a mystery. Maybe she wasn’t just embittered, maybe she was cruel too, and wanted to make Calida believe she had a chance at taking the prize before snatching it out of reach. Calida knew she would receive no invitation. Simone would prefer Teresita. Everyone preferred Teresita. Did Daniel prefer her? Ever since their disastrous trip into town, her twin had made it perfectly clear where her ambitions lay. Calida had been stupid to think she could pull off a stunt like that, anyway—chasing Daniel into a world she had no place in, not once stopping to think about his reaction, or whom he might be with, or what he would say. Teresita could wing these things, but she couldn’t. It had been so unlike her, her silly attempt to be more like her sister, and see how it had backfired.

Perhaps it wouldn’t be so bad if Teresita went away.

‘I can’t wait!’ Teresita could scarcely contain her excitement. Calida had seen the way her sister had eyed Simone’s jewellery, admired her gleaming car, envied her chic wardrobe and, at one point, salivated over the bulging wallet that the actress had laid down on the counter, fat with banknotes. This was what her twin desired.

Afterwards, Calida stayed behind to wash the dishes. She recalled a phrase her papa had used, as they had lingered outside the store in town for her photographs to be developed. He’d stroked her hair and said: Good things come to those who wait.

She couldn’t help wondering if bad things did, too.

Later, when Julia had gone to bed, Calida sat on the veranda and gazed up at the stars. Are you there, Papa? Are you with me? If Diego were alive, he would be on her side. She wasn’t even sure what battle she was fighting, but she knew he would be on her side. Now, it seemed as if everything was slipping from her grasp, too fast, too much change, and she didn’t know who she was any more. She didn’t know who her twin was, and, in a lifetime of reflections, of using the other to define oneself, it was a question that frightened her to death. She longed to find a way to reach Teresita, to remind her that the bond they had was stronger than this. But she couldn’t.

Her thoughts were punctured by the sound of laughter. She stood and followed. Who was her sister talking to? Julia had long since fallen asleep.

It was with a growing sense of dread that she arrived at Daniel’s cabin, and heard Teresita talking inside. Her twin spoke animatedly and vivaciously—no wonder people liked spending time with her. Words didn’t come so easily to Calida; they seemed too important, too permanent. She’d never be able to charm Daniel that way.

Anxious, she peered through the window, and saw the pair sitting at his table.

Jealousy boiled in Calida’s blood. Her sister hung on to his every word, every so often touching his arm, or resting her chin on her hand in a way she had learned from their mother. Sensuous. The word, sinuous and sinister, sewed itself under Calida’s skin with a sharp needle. You’ll never be sensuous. You’re not pretty enough.

‘Calida’s confused, you know,’ Teresita was saying.

Calida froze, her heart wedged in her chest. She wanted to interrupt, but all she could do was stay and listen, her feet rooted to the ground, her breath held.

Daniel hesitated. ‘About what?’

Teresita sighed as if she were about to expose a truth she would rather not. Calida saw their mother, again, in the mannerism. ‘She likes this boy …’ she began.

‘Oh,’ said Daniel. For a crazy second, Calida thought her sister was going to do the right thing, at last, to tell him how Calida felt, describe her unwavering commitment; although the prospect was appalling it was also a kind of relief—perhaps it took a soul as brave as Teresita’s to make it happen. But then she said:

‘It’s this boy in town. She’s obsessed with him. That’s why we came to Las Estrellas. I kept telling her she should give up. She can be so desperate sometimes.’

Calida began to tremble. Her ears rang, high and sharp.

‘She should set her sights lower,’ Teresita finished.

Daniel looked confused. Disappointed. No, she couldn’t work out his expression. ‘I don’t think your sister needs to do that,’ he said.

‘She likes him because he’s rich. Money’s really important to her. Once, I suggested that you two might have a thing … but the fact is you’re not her type. Calida wants someone who can treat her—buy her things …’

No! Calida silently stormed. No! That’s you! That’s all you! That’s not me!

‘Not like me,’ said Teresita, on cue. She put a hand over Daniel’s.

Mud filled Calida’s mouth and lungs. Heat prickled her fingertips.

‘I really like you, Daniel.’ Teresita’s beauty was amazing in this light, her huge, soulful eyes glittering. ‘I’ve never kissed anyone before. Will you teach me?’

Calida could hear no more. Without knowing how, she stumbled to the outhouse door, her vision splintering and a roar in her throat, and knocked.

‘I need Teresita at the house,’ said Calida, when Daniel answered. She was stunned at how steady she sounded. She even smiled for her sister. ‘It’s important.’

Teresita shot Daniel a lingering look before slipping out into the night.

‘You can’t control me for ever, you know,’ she slammed, striding ahead through the dark. Calida didn’t respond. She was mute with hurt and fury.

She watched the back of her sister’s head and for the first time ever, hated it. Calida had disliked her in the past, envied her, coveted her, but she’d never hated her.

Only when they were in their bedroom, and Calida shut the door behind her, did she cough up the rope that was strangling her. ‘How dare you?’ she spat.

‘What?’

‘I heard everything. The lies you told Daniel.’

‘So?’

‘How could you?’ Calida choked. ‘I know you like him. I know you don’t care that I do as well. I might not understand it, but I know it. But how could you lie?’

Teresita turned away, started fumbling pointlessly with her belongings.

‘Don’t you dare turn your back on me,’ Calida seethed.

Her twin whirled round. ‘Don’t you dare tell me what to do! I’ve had enough of you telling me what to do!’

‘You knew how I felt,’ Calida said, her voice shaking, ‘how I feel.’

‘Am I not allowed to have feelings?’ Teresita lashed. ‘Have you got first dibs on those too? Tell me something, Calida: just what do I have that wasn’t yours first?’

Calida blinked. ‘I don’t know what you mean.’

‘I’m sick of it.’ Teresita’s voice skidded, a flicker of vulnerability, but she caught it. ‘I’m sick of playing second. I’m sick of you deciding what my life should be. Can’t I have a little fun? Can’t I be my own person? Or do I have to ask your permission every time?’

‘It isn’t like that.’

‘It’s always been like that. And I thought you knew every little thing about me, Calida. You know me better than I know myself, right? That’s what you always say. Have you ever stopped to think about how that makes me feel? Like I don’t even have that. I don’t even have me, because you got there first!’

‘How can you say this? After everything I’ve done—’

‘I didn’t ask you for any of it! Just because you chose to hold my hand doesn’t mean I have to be grateful for it. You thought you were helping but all you were doing was holding me back. So, what, I’m supposed to kiss your feet for the rest of my life? Thank you for stifling my dreams? Carry a debt I never even wanted?’

‘I thought I was looking after you.’ Calida tried to understand, to see things from another point of view, but her thoughts jammed. ‘I’m your sister—’

‘No.’ Teresita looked deep into her eyes, that steely resolve the last remnant of the twin Calida recognised. ‘Let me tell you who you are, for a change. You’re someone I’m not sure I even like any more. You’re someone I’ve already left behind. You’re someone I don’t have anything in common with except the misfortune of a birthday.’

Calida opened her mouth but no words came out.

‘Daniel’s not interested in you, Calida. I was doing you a favour. The longer you carry around this pointless torch, the more embarrassing it’s going to get.’

Calida’s eyes filled with tears but she kept them from falling.

‘But he’s interested in you … right?’

‘He was an experiment,’ said Teresita. ‘To see if I could.’

That was the worst part. At least if she cared, it might have made sense.

Calida’s face burned. ‘So all this was for nothing.’

‘Not for nothing: he was a decent enough distraction.’

‘You don’t know a thing about him.’

‘I know more than you. I know he likes pretty girls—like me.’

It was the first time their physical difference had been acknowledged: even at this hour, a cheap, callous shot. The words hit Calida like a punch.

‘Shut up,’ she whispered.

‘Why should I?’ Teresita threw back. Now the flame had been lit, an inferno galloped in its wake. All the suffocated hurt, the petty jealousies, the spite, all the hidden scars and buried grudges and smothered indignations, it all came tumbling out. ‘For once I won’t shut up when you tell me to—I won’t do a thing you say. I’m tired of doing what you say! And do you know what, Calida? If you’d given Daniel five more minutes, he’d have kissed me—and he’d have liked it. I’d have told you and loved every second, because finally I’d have something you didn’t have—I’d be the winner, not trailing behind, being told she’s too small or too precious or whatever you use to tie me down. I hate it here! I hate it! Can’t you see that?’

Calida felt herself disintegrating, like a pillar of salt in the wind.

There may have been a moment when Teresita could have reached out, like a hand over a cliff edge, and hauled them both to safety; a point at which it was still salvageable, the damage could be explained, taken back, remedied with trust and confidence and time.

The moment never came.

Calida saw red, then. She thought of all she had done for this person, loved and cared for her, put her first and kissed away her tears—and this was how she was repaid? Suddenly she was across the room, she didn’t know how, and her arm was in the air. She struck her twin round the face, sharp and clean, pushing her into the wall with a loud, sickening thump. Calida hit her again, and again, this perfect princess who had turned into a monster, her blows carrying the weight of a thousand soldiers.

‘I wish you’d just disappear,’ said Calida, when she was done.

The words hung between them, growing in the silence, and the longer they hung there, unrescued, untempered by an antidote, the huger they became.

‘Simone Geddes is going to choose me,’ hissed Teresita. ‘You do realise that, don’t you? And when she does, and when I’m gone, I hope I never come back. I hope I never see you or this dying shit-hole ever again. I’m going to make it, Calida. Do you understand? I’m going to make it, far away, without your help or any fucking thing you do for me. I’m going to make it on my own.’

Calida didn’t stay to hear any more.

She turned on her heel and slammed the door behind her.

9

A week later, Teresa left for England.

Simone Geddes organised her travel, starting with the glimmering car that collected her from the estancia, and a suited driver who touched his cap when she climbed in. It was cool inside; a citrusy fan that came from vents in the front. The seats were made of leather, polished and smooth and the colour of vanilla ice cream.

The road dissolved in a blur as the car hurtled towards the airport.

Teresa held the locket around her neck, its pendant clutched in her palm. It was pebble-sized and gold. Diego had given both his daughters identical ones when they were small; she remembered the day she and Calida had unwrapped them, delicate in tissue, and had helped each other tie the catch. Packing the last of her things for London, Teresa had thought twice about bringing hers, had fastened it only at the last moment, a final, muddled grasp at the sister she didn’t say goodbye to.

A tear slipped out of her eye. Fiercely, she wiped it away.

She would not cry. She would survive. She didn’t need Calida.

A sign flashed past. AEROPUERTO 10KM.

Teresa closed her eyes. Simone’s invitation was a chance at the life she craved. A chance to leave the slums behind and head for the starlight …

Besides, she would be back in a month—and it would all feel like a dream. She would confront her sister then. For now, she wouldn’t think of her at all.

But it was her mama’s face that stayed with Teresa, then and all the way to England. How Julia had clung on tight as she’d said farewell, hardly able to speak through her tears. How she’d said to her: ‘I’ll always love you. This is for both of us.’

10

December 2014

Night

She woke with her hands bound. They were bound at her waist, the fingers clasped as if holding an invisible bouquet. Her ankles were tied, too. She kicked out and both legs moved together on the hinge of her knees. A dry expulsion, half breath, half groan, seeped from her throat and hit a damp, mysterious wall. Instinctively, she bit down. Her mouth was stuffed with cloth. Her lips were sealed with tape.

At first it was pitch dark, then, as her eyes adjusted, she became aware of a faint, pulsing orange. It shone from high and crept across the floor in a ladder. She imagined climbing it, unsure which way was up, and escaping that way.

Escaping what?

The question emerged with little sense of urgency. She lived each second, gradually, one second then another, deciding whether or not she was alive.

Sounds filtered through. A city siren, screaming to loud then fading to quiet then gone; a dog barking; a man calling to another man, their voices passing at an unknown distance. She wondered where they were going, if she could go with them.

Soft things pattered at a window, then her eyes adjusted and she saw white flakes, thick white flakes of winter tumbling through the black night like moths.

It was Christmas in New York. The idea was an anchor, some reminder of where she was and where she had come from. Out on the street, passers-by would be wrapped in coats and scarves, mittened hands holding another’s, noses red and hearts warm as they planned their trip home, to heat, to friends, to safety.

She closed her eyes. Perhaps if she fell asleep a while longer, she was so tired, so very tired, and when she woke up she would be home … Home …

And then she heard a voice, pulling her back from the brink of slumber:

Get out.

It was clear and precise and she trusted it.

You’re in danger. Move. Get out. Now.

She tried to push herself up on her elbows but her stomach couldn’t take it. Ropes inside her twisted and pulled; she whimpered, growled, writhed in anger.

The door opened.

She blinked, drinking the room in, desperate to see more.

Footsteps.

Someone was with her, standing right there, over her, looking down. She froze. The person stood very still. Time stopped.

She tasted terror.

‘Hello,’ said a voice. ‘I’m glad I found you. Are you glad to see me?’

PART TWO

2000–2005

11

London

Teresa Santiago woke to the sound of shouting. It was in a language she didn’t understand, and the ferocious, high-pitched squawks shot back and forth like two cats scrapping in a yard. One belonged to Simone, a literal far cry from the dulcet tones in which she addressed Teresa. The shouts were coming from downstairs, a concept she was only now getting used to since she’d only ever lived in a single-storey dwelling. She got out of bed and stood in her silk pyjamas, wondering if it was safe to emerge.

After a while, the screams died down. There followed a series of stomps and the bang of a slamming door. Teresa pictured the other girl who lived here, the blonde with the upturned nose, throwing herself on the sheets and bawling.

She stretched, and the room yawned with her. It was enormous. The ceiling stood at three times her height, with delicate cornicing like the icing on a birthday cake. A glinting chandelier hung from a central floret. The curtains were duck-egg blue and billowed gently against the open windows, of which there were three; huge and as perfectly rectangular as if they belonged in a dolls’ house. Through them, the hum of London swam up on the breeze. Her four-poster bed was swathed in peach satin, plumped with dozens of pink cushions, and the mattress was as deep and squidgy as the honeyed brioche Teresa was occasionally served for breakfast.

It was a princess’s bedroom. At lights-out, Teresa would lie still and wait for her eyes to become accustomed to the dark, and when they did she would test herself by closing and then opening them again, half fearing that the room would have been swallowed up, and she would find herself back at home in Patagonia, Calida asleep on the bunk below and the moon looking in through the window. She couldn’t believe that all this was hers. OK, it was on loan, it wasn’t forever, but boy was it something else. London was another universe. Simone Geddes’ mansion was incredible. At the beginning she had got lost every hour, exploring the furthest reaches of the house and then forgetting her way back. Simone had a loft, a cellar, a games suite, and a spa; they had a library and a music room and a reading room; they had a separate area where they ate their meals and drank their drinks and the lounge alone was bigger than the entire farmhouse back in Argentina. All the floors were piled one on top of another, like a stack of pretty boxes. When Teresa first arrived, she’d hurt her neck looking up at them all and Simone had laughed affectionately and stroked her arm.

‘Welcome to my world,’ she’d whispered.

It truly was the realm of her imaginings. Everything she had hoped for and dreamed of. Her old life ceased to exist. Poverty, struggle, longing. And Calida …

Teresa pushed away thoughts of her twin. She suffered a tangle of emotions whenever she thought of her: anger, hurt, frustration, and sadness; it was easier to bottle them up. Calida had wished her gone. She would be happy back on the farm, with Daniel, who was the only person who mattered to her anyway.

I wish you’d just disappear …

Though the bruises had faded, the scars were still tender to touch. Fine, Teresa thought, you got what you wanted. See if I care. I’m having the time of my life.

There was a knock at the bedroom door. ‘Ms Santiago?’

The maid stepped in. Vera was a kind, plump, Hispanic woman. Once or twice they had chatted in Spanish, but Vera always cut it short because, she explained, she wasn’t meant to converse with the household. ‘I’m not the household,’ Teresa said, ‘I’m a guest.’ But Vera had backed out of the room and stayed quiet on the matter.

Privately, Teresa wondered if the maid was content working here. Simone spoke sharply to her, as did the other children. The blonde girl, Emily, acted as if Vera didn’t exist, yet had vicious words to impart when her trail of bubblegum wrappers, cigarette butts, and empty bottles of cola failed to be cleared promptly from the side of the swimming pool; while the boy, Lysander, with whom Teresa hadn’t had much contact because she found him daunting, but thrillingly so, liked to make her blush.

Now, the maid wheeled a silver trolley across the carpet, which she brought to a stop at the foot of Teresa’s bed. She bobbed a short curtsey.

‘Gracias,’ said Teresa, marvelling at the sight.

‘De nada—can I bring you anything else?’

‘No, thank you.’ Teresa had never been treated with such reverence: she felt she could ask for anything—a bicycle, a sandcastle, a unicorn—and it would be brought straight to her, with apologies for the delay. Vera nodded and left the room.

The breakfast was sumptuous. Teresa lifted the metal cloche and underneath was a spread of eggs, bacon, mushrooms, and tomato, diamonds of toast with the crusts cut off, a pat of butter in the shape of a seashell, a bright glass of orange juice and a goblet of fresh yoghurt topped with blueberry compote. She wolfed the feast.

Excitedly, she dressed. Simone was taking her shopping today and she couldn’t wait. She’d heard so much about luxury clothes and seen Simone’s own dazzling wardrobe, and could picture the stores with their polished displays and glossy sales people; the buzz and zing of money as it flashed in and out of the till.

In the hallway, she stopped. Emily was blasting music from her bedroom and a sign on the door read: KEEP OUT: BITCH WITHOUT A MUZZLE.

Emily’s room was forbidden territory and Teresa knew she wouldn’t be welcome. Since she’d arrived, Emily had barely said two words to her. Frequently she caught the girl scowling at her, and once Emily had brought her friends over and Teresa knew they were giggling and gossiping because they kept looking over and then hiding their smiles behind their hands. Teresa wished she could speak English because then she could explain that Simone had invited her and, since she was here, they might try to get along … It was only a couple more weeks, after all.

Holding the banister, she descended the staircase. It was wide and carpeted, its lofty white walls adorned with giant photographs of Simone at work; Simone in the director’s chair, mingling with co-stars or donning a variety of glamorous wigs. Down in the vestibule stood an impressive cabinet of awards. Julia had said that Simone was famous, but Teresa was beginning to see that for the severe understatement it was.

In the kitchen, the actress was stirring coffee and gazing out of the window to where a pool boy was raking leaves from the water. She was muttering something ominously to her husband, and Teresa identified the sound of Emily’s name.

Noticing their guest, Simone’s face lifted. She turned, arms outstretched.

‘Good morning, sweetheart!’ She gave Teresa a hug. Simone was very affectionate for a hostess and Teresa never quite knew what to do, so she hugged her back and this seemed to be the right thing. Over her shoulder, she spotted Brian eating toast messily at the counter. Brian Chilcott was a director, which meant he told people on movie sets where to go and how to act. He was overweight, and had a florid, disinterested face, and wore ties that looked uncomfortably tight at the neck.

He delivered a wink to Teresa. Diego used to wink at her sometimes but this wink was different; there was something latent in it, a threat too cloudy to name.

‘Are you ready for our shopping trip?’ Simone encouraged.

Teresa didn’t understand. Brian put in: ‘Are you going to teach her English?’

‘Shut up, Brian. Keep your booze-addled nose out of it.’

Teresa didn’t grasp what they were saying, but she heard the bitterness in Simone’s voice. Brian put down his toast and shrugged on his jacket. On his way out, he pecked Simone on her cheek. She turned away but he wouldn’t be deterred.