Полная версия

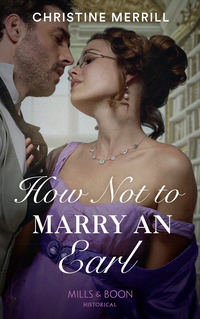

Dangerous Lord, Innocent Governess

‘That man,’ muttered the Duchess in frustration and gave a small stamp of her foot.

‘Indeed.’ Daphne swallowed, trying to control the strange feeling she had had, as her cousin’s husband had smiled at her. He had stared at her far too long, until the look in his eyes had gone from sullen to seductive. He had looked at her as a wolf might look at a lamb.

She was sure that the Duchess had not seen the worst of it, thinking the man had been rude and not threatening. For when she turned to Daphne, she had a grim smile that said she would not be crossed in this, no matter how stubborn the master of the house might be. ‘Lord Colton has proved difficult on the subject of his children’s care.’

‘They are his children,’ Daphne said softly, rather surprised at how little the Duchess seemed to care about the fact.

‘Of course,’ the Duchess responded. ‘But recent events have left him all but unfit to care for them. As a close friend of the family, I feel a responsibility to help him through this difficult time.’

‘You knew Lady Colton?’ Daphne smiled eagerly. She might have an ally, if the woman had also known Clare.

‘I knew her. Yes.’ And now the Duchess’s look was one of distaste. She offered nothing more, before changing the subject. ‘But come, you must be eager to see the nursery wing and meet your charges.’ She rose quickly and preceded Daphne to the door and out into the hall, as though the merest mention of the children’s mother hung in the air like a bad smell.

As they walked up the main stairs, Daphne paused for a moment and glanced behind her. So this was where it had happened. She could almost imagine her cousin, who had been so full of life, lying dead below her on the floor of the entry. She shook off the image to further examine the scene of the crime. Smooth marble treads, and an equally smooth banister that might have denied an adequate grip to the woman who had struggled here.

She glanced at the floor to see faint proof that a rug had been present and was now removed. So the poor carpet had taken the blame. A loose corner, a trip and a fall. Perfectly ordinary. Most unfortunate.

But Daphne believed none of it. Clare had used the stairs for twelve years without so much as a stumble. There was nothing to be afraid of, if someone was not here to push you down. When she was finished in this house, everyone would know the truth and Clare would be avenged.

The Duchess did not notice her pause, absorbed by her own thoughts, which did not concern the unfortunate death of the mistress of the house. She gave a helpless little shrug. ‘I might as well tell you, before we go any further, that there is a small problem that I have been unable to deal with.’

‘Really.’ There were many problems with this house, and none of them small. Daphne wondered what would incite the Duchess to comment, if the death of Clare had not.

‘In my letter to you, I promised something I could not give. The bedroom just off the nursery is the one intended for the governess. Convenient to the classroom, and next to little Sophie should she need you in the night.’

Daphne nodded.

‘The oldest girl, Lily, has taken the room as her own. I have been unable to dislodge her from it. The two older children care deeply for the littlest girl. And in the absence of a regular governess they have taken the duties of Sophie’s care upon themselves.’ For a moment, the Duchess looked distressed, nearly to tears over the plight of the children.

Forgetting her station, Daphne reached out a hand to the woman, laying an arm over her shoulders. ‘It will be all right, I’m sure.’ It was comforting to see that the Duchess cared so deeply for the children, for it made her actions in the Colton house seem much less suspicious.

The Duchess sniffed, as though fighting back her emotion. ‘Thank you for understanding.’ She walked to the end of the hall and opened the door to the servants’ stairs, looking up a flight. ‘There is a small room at the top of the house. Only fit for a maid, really. But it is very close to the children. And yet, very private. There is nothing at all on this side of the house but the attics, and the one little place under the eaves. And it is only until you can persuade Lily to return to her own room.’

Daphne looked up the narrow, unlit staircase, to the lone door at the top. ‘I’m sure it will be adequate.’ It would be dreadful. But it was only for a few weeks. And living so simply would help her remember her position.

‘Shall we go and meet the children now? I have sent word that they are to wait for us in the schoolroom.’ She led the way past two bedrooms, which must be Sophie’s and the one Lily had usurped, to a small but well-stocked classroom. There were desks and tables, with a larger desk at one end for her, maps and pictures upon the walls and many shelves for books.

Remembering how she had felt as a child when cooped up in a similar room, Daphne was overcome with a sudden desire to slip away from the Duchess, to lead her in hide and seek or some other diversion. Anything that might prolong the time before she must pick up a primer.

The children lined up obediently in front of her, by order of age. Daphne felt a surprising lump form in her throat. They were all the picture of her beloved Clare. Red hair, pale complexions, fine features and large green eyes. Some day, the two girls would be beauties, and the boy would be a handsome rakehell.

The rush of emotion surprised her. She felt a sudden, genuine fondness for the children that she had not expected. She did not normally enjoy the company of the young. But these were the only part of her cousin that still remained. She had to overcome the urge to talk to them of the woman they both knew, and to reveal her relation to them. Surely it would be a comfort to them all to know that Clare was not forgotten?

But then she looked again. The light behind their eyes was the same suspicious glint she had seen in the man behind the desk on the floor below. They had also inherited the stubborn set of his jaw. Without speaking a word to each other, she watched them close ranks against her. They might smile and appear co-operative. And her heart might soften for the poor little orphans that Clare had left behind. But that should not give her reason to expect their help in discovering the truth of what had happened to their mother, or in bringing their father to justice.

She smiled an encouraging, schoolteacher’s smile at them, and said, ‘Hello, children. My name is Miss Collins. I have come a long way to be with you.’

The boy looked at her with scepticism. ‘You are from London, are you not? We make the trip from London to Wales and back, twice a year. And while it is a great nuisance to be on the road, it is not as if you have come from Australia, is it?’

‘Edmund!’ the Duchess admonished.

Daphne chose to ignore the insolence, and redoubled her smile. ‘As far as Australia? I suppose it is not. Do you find Australia of particular interest? For we could learn about it, if you wish.’

‘No.’ He glanced at the Duchess, who looked angry enough to box his ears. He corrected himself. ‘No, thank you, Miss Collins.’

‘Very well.’ She turned to the older girl. ‘And you are Lily, are you not?’

‘Lilium Lancifolium. Father named me. For my hair.’ When she saw Daphne’s blank look, she gave a sigh of resignation at the demonstrated ignorance of the new governess. ‘Tiger Lily.’

‘Oh. How utterly charming.’ Utterly appalling, more like. What kind of man gifted his first child with such a name? And, worse yet, a girl, who would someday have to carry that name to the alter with her. Clare’s frustration with the man had not been without grounds.

Daphne turned to the youngest child. ‘And you must be little Sophie. I have heard so much about you, and am most eager to know you better.’ She held out a hand of greeting to the girl.

The littlest girl said nothing, and her eyes grew round, not with delight, but with fear. The two older children stepped in front of her, as though forming a barrier of protection. ‘Sophie does not like strangers,’ said Edmund.

‘Well, I hope that she will not think me a stranger for long.’ Daphne crouched down so that she might appear less tall to the little girl. ‘It is all right, Sophie. You do not have to speak, if you do not wish. I know when I was little I found it most tiresome that adults were always insisting I curtsy, and recite, and sit in stiff chairs listening to boring lessons. I’d have been much happier if they’d left me alone in the garden with my drawings.’

The little girl seemed taken aback by this. Then she smiled and shifted eagerly from foot to foot, tugging at her older sister’s skirts.

In response, Lily shook her head and said, ‘Sophie is not allowed to draw.’

‘Not allowed?’ Daphne stood up quickly. ‘What sort of person would take pencils and paper away from a little girl?’

Edmund responded, ‘Our last governess—’

‘Is not here.’ Daphne put her hands on her hips, surprised at her own reaction. She had not meant to care in the least about the activities of the children. But she found herself with a strong opinion about their upbringing, and on the very first day. ‘You…’ she waved her hand ‘…older children…’ it took a moment before she remembered that calling them by name would be best ‘…Edmund and Lily. Look through your books and see if you can find an explanation of the word tyranny. For that is what we call unjust punishments delivered by despots who abuse their power. And, Sophie, come with me, and we will find you drawing supplies.’

The older children stood, stunned, as though unsure if she’d meant the instruction or was merely being facetious. But the younger child led her directly to a locked cabinet, and looked hopefully at her.

‘They are in here, are they?’ Daphne fumbled for the keys the Duchess had given her at the conclusion of the interview, which fit the doors to the nursery and schoolrooms, the desk and its various drawers. But she could find none that would fit the little cabinet. The girl’s face fell in disappointment. She patted her lightly on the head. ‘Fear not, little Sophie. It is locked today. But I promise, as soon as I have talked to the housekeeper, I will remedy the situation, and you shall have your art supplies again.’

All the children looked doubtfully at her now, as though they were convinced that she would be unable to provide what she had promised.

But the Duchess was smiling at her, as though much relieved at the sudden turn of events. ‘Children, let me borrow Miss Collins to finish arranging the particulars. Then she shall have all her keys and you shall have your paints and pencils.’ She led Daphne back out into the hall, and squeezed her arm in encouragement. ‘Well done, Miss Collins. Barely a minute in the room, and you have already found a way to help the children. You are brilliant. And a total justification of my desire to advertise in London for a woman with exemplary references, instead of dealing with the problem in the haphazard manner this family is accustomed to. I am sure you will do miracles here. You are just what is needed.’

Daphne could only pray that the woman was right.

Chapter Two

The rest of the day passed in a whirl. The Duchess helped her to find more keys, made sure that her things were sent to the little room in the attic and arranged for her salary. When it was nearing supper time, she left to return to her own home, which was only a few miles away. Daphne felt her absence. It was almost as if she had made a friend of the woman, she had been so solicitous.

But now she must strike out on her own, and find the evening meal. Which led to the question—where did the governess usually eat? She struggled to think if she had ever seen one at her own family’s table, or dining with the family in the home of friends. But it was possible, even if they had been there, she would not have noticed. She doubted that they were encouraged to call attention to themselves.

She strolled down the passages of the ground-floor rooms, and found the dining room closed and dark. Wherever the Colton family ate, it was not a formal thing. But if servants were not waiting at table, then they must be below stairs, having a meal of their own. She went to the same stairway that would lead to her room if she followed it upwards to the end. She took the stairs downwards instead, and came out into a large open room with a long oak table set for supper. The servants were already gathered around it.

She came forwards and sat down at a place somewhere about the middle, offering a cheery ‘hello’ to the person next to her, who appeared to be a parlourmaid.

The room fell silent for a moment, and the housekeeper looked down the table toward her. Without a word, the woman went to the sideboard for a fresh plate, for the person Daphne must have displaced. This was handed down the table, and there was much shifting and giggling as the servants around her reorganized themselves according to their rank. It appeared that servants had a hierarchy every bit as structured as that of a fine dinner party above stairs. And Daphne had wandered in and disrupted things with her ignorance.

Once things were settled again, the housekeeper, Mrs Sims, announced, ‘Everyone, this is Miss Collins. She is the new governess that her Grace hired for the children.’

The staff nodded, as though they did not find the Duchess’s interference to be nearly so unusual as the presence of a governess at the servants’ table.

The housekeeper favoured her with another nod. ‘In the future, Miss Collins, you are welcome to eat in your room or with the children. No one here will think you are putting on airs.’ She said it rather as a command, not a request.

It rather put a crimp in her plans to gather intelligence below stairs. ‘Thank you, Mrs Sims. I was rather at a loss today as to what was expected. But I am sure this shall be all right, tonight at least. I wished to meet you all.’ She smiled around the table.

And was met by blank looks in return, and mumbled introductions, up and down the table.

‘Where did the previous governess eat?’ she asked by way of conversation.

‘Which one might you mean? There have been three since the lady of the house died. And many more before that. They all ate in the little dining room in the nursery wing.’

‘So many.’ It did not bode well for her stay here. ‘What happened to them? I mean, why did they leave?’ For the first sounded far too suspicious.

Mrs Sims frowned. ‘Of late, the children are difficult. But you will see that soon enough.’

And there was mention of the difficulties again. But in her brief meeting with them, they had not seemed like little tartars. ‘I am sure they are nothing I cannot handle,’ she lied, really having no idea how she might get on with a house full of children.

‘Then you are more stalwart than the others, and more power to you,’ said the butler, with a small laugh. ‘The first could not control them. And the second found them disturbing. The third…’ he gave a snort of disgust ‘…had problems with little Sophie. Thought the poor little mite was the very devil incarnate.’

‘Sophie?’ Having met the girl, this was more than hard to believe.

‘The master caught Miss Fisk punishing the girl. She had been forcing Sophie to kneel and pray for hours on end, until her little knees were almost raw with it. And the older children too frightened to say anything about it.’ The housekeeper shook her head in disapproval. ‘And that was the last we saw of Miss Fisk. Lord Colton turned her out of the house in the driving rain, and threw her possessions after her. He said he had no care at all for her safety or comfort, if she did not care for the comfort of his children.’

‘Served her right,’ announced the upper footman. ‘To do that to a wee one.’

‘You’ll think so, if he finds reason to turn you out, I suppose?’ asked another.

The boy smirked. ‘I don’t plan to give him reason. I have no problem with the children.’

‘Or the neighbours,’ said another, and several men at the table chuckled.

‘The neighbours?’ Daphne pricked her ears. ‘Do you mean the Duke and Duchess?’

The housekeeper glared at the men. ‘There are some things, if they cannot be mentioned in seriousness, are better not mentioned at all.’

The butler supplied, in his dry quiet voice, ‘Relations are strained between our household and the manor.’

‘But Lord Colton seemed to get on well enough with the Duchess.’

‘There is nothing strange about that, if you are implying so.’ The housekeeper sniffed. ‘The master has no designs in her direction.’

‘No,’ said one of the house maids with a giggle, ‘his troubles were all with the Duke. Her Grace wishes to pretend that nothing is wrong, of course. But she was not here for the worst of it. If she had seen the way the Duke behaved with Lady Colton…’

Now this was interesting. Daphne leaned forwards. ‘Did he…make inappropriate advances?’

A footman snickered, and then caught himself, after a glare from the butler.

But a maid laughed and said, ‘It was hard to see just who was advancing on who.’

‘Remember where your loyalties lie, Maggie,’ murmured Mrs Sims. ‘You do not work at Bellston Manor.’

Maggie snorted in response. ‘I’d be welcome enough there, if I chose to go. My sister is a chambermaid at Bellston. And she has nothing but fine words to say of his Grace and his new Duchess, now that our mistress…’ the girl crossed herself quickly before continuing ‘…is no longer there to interfere.’ She looked at Daphne, pointing with her fork. ‘When her ladyship was alive, I worked above stairs, helping the lady’s maid with the ribbons. And let me tell you, I saw plenty. Enough to know that his lordship is hardly to blame for the way things turned out in the end.’

‘Then you should know as well the reason we no longer see his Grace as a guest in the house.’ The butler was stiff with disapproval.

Daphne’s eyes widened in fascination as the conversation continued around the table.

‘It is a wonder that Lord Colton did not take his anger out in a way that would be better served,’ said a footman, ‘on the field of honour.’

‘Don’t be a ninny. One does not call out a duke, no matter the offence.’ The upper footman nodded wisely. ‘There’s rules about that. I’m sure.’

‘In any case, weren’t all the man’s fault.’

The housekeeper sniffed again, as though she wished to bring an end to the conversation.

‘Just sayin’. There are others to blame.’

The housekeeper tapped lightly on her glass with her knife. ‘We do not speak of such things at this table, or elsewhere in the house. What’s done is done and there is no point in placing blame for it.’

The table fell to uneasy silence, enjoying a meal of beef that was every bit as good as that which she had eaten at home above stairs. Daphne suspected that such meals had gone a long way in buying the loyalty of the servants, none of whom seemed to mind that the master had murdered the mistress.

One by one, the servants finished their meals and the butler excused them from the table to return to their duties. But Daphne took her time, waiting until all but the butler and housekeeper were gone. If there was information to be had, then surely they must know, for it seemed that they knew everything that went on in the house.

But before she could enquire, the housekeeper spoke first. ‘Why did you choose to eat below stairs, Miss Collins?’

‘I thought, since I am a servant, it was appropriate.’

The housekeeper gave her a look to let her know that she had tripped up yet again. ‘A servant now, perhaps. But a lady above all, who must be accustomed to a better place in the household than the servants’ table.’ Mrs Sims looked at her with disapproval. ‘And a lady with a most unfortunate tendency to gossip. It is not something we encourage in this house.’

‘I am sorry. I was only curious. If I am in possession of all the facts, I might be best able to help the children.’

The butler responded, ‘I doubt there is anyone in possession of all the facts, so your quest is quite fruitless. But I can tell you this: the less said about their mother, the better. She was a hoyden, who got what she deserved.’

Daphne let out a little gasp. ‘Surely not. The poor woman, God rest her soul.’

The housekeeper drew herself up with disapproval. ‘You think that knowing the truth will help the little ones? Then here it is, or all you need to know of it. What happened to our mistress was the result of too much carrying on. The children are lucky to be rid of her, however it happened.’

So Mrs Sims suspected something was strange about the death. But the housekeeper’s assessment was most unjust. ‘I hardly think it is fair to believe such things, when you yourself admit that no one knows all the facts in the situation. In the last house I was employed, everyone thought much the same of the only daughter. They were all most censorious, when she was guilty of the smallest breaches of etiquette. She strayed from the common paths in Vauxhall with one of her suitors. And before she knew it, she was packed off to the country in disgrace. I suspect she was no worse than Lady Colton.’

‘Do you now?’ The housekeeper shook her head. ‘Then you are most naïve. If the young girl you mention was already straying on to dark paths with young men, then I suspect it was for more tickle than slap. Perhaps the late Lady Colton would have called it innocent fun and not the death of the girl’s reputation. In fact, I am sure that my lady and the girl would have got on well together. Clarissa Colton would have approved, for the young lady you describe would have been taking a first step toward becoming what she had become: a lady with no discernible morals. It pains me to say it. But her ladyship had no sense of decency whatsoever. No respect for herself, and certainly none for her husband.’

It stung to hear such a blunt assessment of her character. For the housekeeper seemed to agree with Daphne’s parents that her trips to Vauxhall could have put her beyond the pale. And Mrs Sims had predicted Clare’s reaction to the thing well enough—she had said that there was no harm in it at all. She came to her cousin’s defence. ‘Perhaps, if I were married to Lord Colton, a man so distant, so cruel and so totally lost to gentleness, my behaviour would be much the same.’

‘If you were married to him?’ The housekeeper let out a derisive laugh. ‘Quite far above yourself, aren’t you, Miss Collins? His lordship is not good enough.’ She glanced toward the conservatory, as though she could see the master of the house through the walls separating them. Then she said softly, ‘I have worked in this house for almost forty years. I have known Lord Colton since he was a boy. And there was nothing wrong with his character before that woman got her hooks into him. A bit of youthful high spirits, perhaps. A slight tendency to excess drink, and with it, a short temper. Things that would have passed, with time. But under the influence of his wife, he grew steadily worse.’

‘So his misbehaviour is youthful high spirits. But the occasional straying of a girl will permanently damage her character.’

The housekeeper gave her a look that proved she thought her a complete fool. ‘Yes. Because, as you can see, his problems did not render him incapable of making a match.’

‘But I do not see that they have made him a good choice for a husband,’ Daphne snapped in return. ‘In my experience so far, he is a foul-tempered, reclusive man who cares so little for his children that he allows the neighbours to choose their governess.’

Mrs Sims frowned. ‘He cares more for the children than you know. And if you care for them as well, you will see to it that the boy grows up to be the man that his father is, and the girls learn to be better than their mother, and get no strange ideas about the harmlessness of straying down dark paths in Vauxhall Gardens. Good evening, Miss Collins.’