Полная версия

The Holocaust in Czechoslovak and Czech Feature Films

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

Foreword

Introduction

After WWII: The Pioneer

1959–1969: The New Wave

1970–1989: The Normalization

1989–1999: New Beginnings

After 2000: New Approaches

Conclusion

Bibliography

Filmography

About the Author

Literature and Culture in Central and Eastern Europe

Copyright

FOREWORD

This book is based on a study of the same name that was published in the expansive edited volume Cizí i blízcí: Židé, literatura, kultura v českých zemích ve 20. století [Close and Foreign: Jews, Literature and Culture in the Czech Lands in the Twentieth Century] in 2016. This edited volume, and implicitly the present book as well, draws from the theoretical concept of cultural memory, especially as explicated by Aleida Assmann. Memory in the form of collectively shared images of the past has spatial as well as social dimensions and its own history. Memory is related to the construction of a collective identity as well as to nationalism and the presentation of national and social stereotypes––these also create the stereotypes of Jews in literature. This idea also applies to the theme of this book, which deals with images of Nazi persecution of the Jews during World War II in Czechoslovak and Czech film.

A film is an artistic structure, one composed of various signs—visual, audio, and verbal. Unlike a literary work, a motion picture is always the result of teamwork and is more dependent on financing for production and distribution. Therefore, studying cinematic works, particularly ones about the Holocaust, cannot focus just on a close analysis of specific cinematic methods and images. This is particularly true for films that were made under the conditions present in Czechoslovakia after 1945. The Communist era (1948–1989) was marked by a varying degree of latent (and often even open) anti-Semitism, usually in the guise of “fighting against Zionism”. If in Western Europe, including West Germany, the Shoah became a serious, socially and politically relevant theme, then the same applies to Czechoslovakia and the other countries of the Eastern Bloc. Coming to grips with the Holocaust, and also with the complicity of some Czechs and Slovaks in the persecution of Jews, has also opened up other traumatic topics from the recent past, such as the forced transfer of the ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia after the war or Stalinist totalitarianism.

Therefore, this book has two focuses. On the one hand, it charts the social and cultural framework in which the studied films were made, and how this framework changed. The fact alone that between 1948 and 1958 and again between 1970 and 1979 not a single feature film about the Shoah was made in Czechoslovakia tells us a great deal about the strict nature of state censorship. In contrast, the easing up of censorship, the decentralization of cultural life in the 1960s, and the elimination of censorship after 1989 resulted in boom of such films, some of which received worldwide fame (e.g., The Shop on Main Street by directors Ján Kadár and Elmar Klos), whereas others were remarkably experimental (e.g., Diamonds of the Night by Czech New Wave director Jan Němec). Particularly in the 1960s, there was a subversive element to Holocaust themes in Czechoslovak cinema and literature. Therefore, the author focuses great attention on the films made in this period.

The second focus of this book is on cinematic language. The author studies the composition of and narration in each film (e.g., the depiction of the war and the Shoah as a narratively closed versus a narratively open event), genre aspects of the films (e.g., the use of comedy and humor), convention and innovation in presenting motifs and characters (the division of gender roles, the character of the “good German”). She pays particular attention to the portrayal of stereotypes and countertypes in the films, where already well-known images, situations, and backdrops are repeated and which meet viewers’ expectations or, in contrast, which form countertypes and countersituations that go against the grain. Thus, the prewar life of Jewish families is often depicted as idyllic; such portrayals often involve religious rituals or objects (menorahs), even though most Czech Jews were integrated at the time and had a distant relationship with their Judaism. Persecution during the war is presented by means of the yellow Star of David and groups of Jews leaving for transports. These stereotypes have also changed over the course of the decades; for example, in recent years, images of brutal violence and sex have become much more common in Holocaust-themed films.

Many of the studied films are adaptations of literary works. In examining this media transformation and the differences between the poetics of literature and film, the author follows in the footsteps of other Czech scholars who have systematically dealt with this phenomenon: Marie Mravcová, Petr Mareš, Petr Málek, and Petr Bubeníček. Therefore, this book is also a contribution to adaptation studies, a rapidly developing field of scholarship.

Šárka Sladovníková is a young scholar and member of the team at the Centre for the Study of the Holocaust and Jewish Literature, which was founded in 2010 at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University in Prague. Since it was established, this center, the only of its kind in the Czech Republic, has worked with German and Polish scholars, particularly from the Forschungskreis Holocaustliteratur und -kultur im mittleren und östlichen Europa, which Reinhard Ibler founded and heads at Justus-Liebig-Universität in Gießen. As part of this collaboration we have held several international workshops and published seven joint books. This book, too, is the result of our cooperation.

March 2018

Jiří Holý

INTRODUCTION

The Holocaust became a theme in Czechoslovak film three years after World War II.1 Between 1948 and 1958 only one film about the Holocaust (Distant Journey) was made; the lack of other such motion pictures can be explained as a consequence of Stalinist anti-Semitism. The first group of films focusing on Holocaust themes appeared in the 1960s during the European cinematic New Wave. Over the course of a decade, about a dozen films were made that are still considered part of the Czechoslovak film canon due to their outstanding quality. After the violent suppression of the Prague Spring by the armies of the Warsaw Pact in August 1968, production of Holocaust-themed films ceased for another ten years as a result of “Normalization”. From 1970 to 1979 not a single motion picture was made about the Holocaust. After 1989 there was a renaissance in these films, which continues until today. The approach to this topic has changed over time—from suppressing Jewish themes in the 1950s and early 1960s to emphasizing them after 1989.

Film has great potential for bringing the past to life for viewers and for influencing how it will be stored in their memories. This potential is strengthened by the illusion of reality present in film narratives:

Of all art forms, film is the one that gives the greatest illusion of authenticity, of truth. A motion picture takes a viewer inside where real people are supposedly doing real things. We assume that there is a certain verisimilitude or certain authenticity but there is always some degree of manipulation, some degree of distortion. (Annette Insdorf in: Imaginary Witness 2004)

Narrative is the basic principle of film (as well as of epic storytelling): “[…] all films, we now know, are fiction, whose impression of reality is built on the coherence of the narrative world they establish” (Baron 2006, 15). The difficulty of capturing the Holocaust on screen is also a result of the “non-communicable nature” of survivors’ experiences. When compared to literature, a film scene is highly specific and subjective. “Whereas words engender the imagination, film images show a sensorially concrete reality” (Mravcová 1990, 10).

This book2 examines how narratives about this theme developed, how representations of Jewishness changed, and whether literary stereotypes appear in these films. It focuses on feature-length films; selected documentary films, shorts, and animated films are mentioned in footnotes where relevant.3

1 I would like to thank Mr. Karel Sieber, archivist at Czech Television, for greatly assisting me with my research.

2 This book was supported by the Prague Centre for Jewish Studies (Rothschild Foundation).

3 Some feature films are mentioned only in a footnote. These films are Smrť sa volá Engelchen [Death Is Called Engelchen, 1960], Boxer a smrť [The Boxer and the Death, 1962], and Námestie svätej Alžbety [St. Elisabeth Square, 1965]; and they were filmed by Slovak directors in Slovak language.

AFTER WWII: THE PIONEER

Alfréd Radok’s (1919–1976) Daleká cesta [Distant Journey, 1949]1 was made just three years after the war. It is based on a semi-autobiographical film treatment titled „Cesta“ [Journey] written by Erik Kolár (1906–1976).2

The film’s story, part of which takes place in the Terezín ghetto, was inspired by the fate of Radok’s father, who was of Jewish extraction and died as a political prisoner at Terezín. Radok himself was interned in 1944 at the Klettendorf concentration camp. In his film, he wanted to give a true portrayal of the recent past and expose the falseness of Nazi propaganda. In one interview, he stated:

Hitler’s name calls a picture to my mind: A little girl, like a baby doll, hands Hitler a bouquet of wild flowers. Hitler bends towards her, smiling with affection. […] This picture of Hitler with the little girl, every overly ostentatious ceremony, it all is somehow related and adds up. When you sum it up, all of a sudden the truth emerges. The whole truth, of course properly organized, with the right editing: ceremonies, parades, little girls, and concentration camps, in that order. […] Whoever sees just Hitler and a girl with flowers doesn’t see anything at all. […] I tried to emphasize the paradox that many people––and this goes for more than just Communist Czechoslovakia––simply don’t see things, don’t want to see them, and just see Hitler with a little girl. (Radok 2001, 80)

Distant Journey did not meet the ideological requirements of the new regime formed after the Communists came to power in February 1948. Therefore, the film was denied a gala premiere and was almost immediately removed from the main cinemas in the centre of Prague and was screened only in outlying districts and in movie theaters outside of the capital.

It was a tragically premature and anachronistic work of art. […] The film was labelled “existential” and “formalistic”. After a very brief run, it was withdrawn from public showing and for almost two decades was locked away in the Barrandov vault. (Škvorecký 1971, 41)

It is paradoxical that this film was stigmatized in Czechoslovakia, while it met with great success abroad. The Communist regime prided itself on Distant Journey at foreign film festivals. Distant Journey was even screened in the USA, where it was compared to Orson Welles’s famous Citizen Kane (1941).

The plot of Distant Journey begins in Prague in March 1939. A doctor’s assistant haughtily suggests to Hana Kaufmannová (played by Blanka Waleská), a young Jewish female doctor, that she should leave the clinic. The film depicts the life of the Kaufmann family and of Toník Bureš, a Czech doctor, who falls in love with Hana and marries her. Hana’s parents and younger brother are deported to Terezín. Toník sets out to clandestinely visit the family, but he does not get to Terezín in time; they have already been deported to the East. Later, Toník, as the husband of a Jewess, is interned in a labor camp. In the end, Hana too is interned in Terezín, where she as a doctor helps out during an outbreak of typhus. From her family, only she and Toník live to see the end of the war; in the final scene, they walk through the Terezín cemetery.

Figure 1: Distant Journey: “Šlojzka”, the space where incoming Jewish prisoners in the Terezín ghetto were placed. Source: National Film Archive Prague

The Holocaust is the central theme of the entire story. The filmmakers were aware of spectators’ ignorance stemming from the short amount of time that had passed. Therefore, they included in the film a great amount of information about the persecution of the Jews, primarily incorporating it into dialogue:

Hana: “I want to look great for the theater.”

Toník: “You really like nice things, don’t you?”

Hana: “I do. I love getting dressed up. You know, Toník, I couldn’t say good-bye to all this. […]”

Father Kaufmann: “But Hana, you know we aren’t allowed to come to the theater since yesterday.”

Kaufmann: “The Jews have also been thrown out of the state office. Jewish lawyers can’t practise. Our Honzík can’t even go to the playground, or to Sokol [a patriotic gymnastic organization]. It seems he might not even be allowed to go to school. […] I am not going to wait here to die.”

Reiter: “And where do you want to go to wait?”

Kaufmann: “Refugees are still being accepted in Brazil. The Pick family has left for Canada. One of our relatives lives in Puerto Rico.”

Other pieces of information are shared visually and require no commentary, for example, in the scene when children from the East arrive in Terezín.3 Hana takes them to the showers. When the small children see the showerheads, they begin to scream; panicking and shouting “gas”, they run away. In the entire film, there is not one mention of the murder of Jews in the gas chambers. The filmmakers, however, assumed that the viewer would already know about the gas chambers, and therefore only hinted at them in the film.

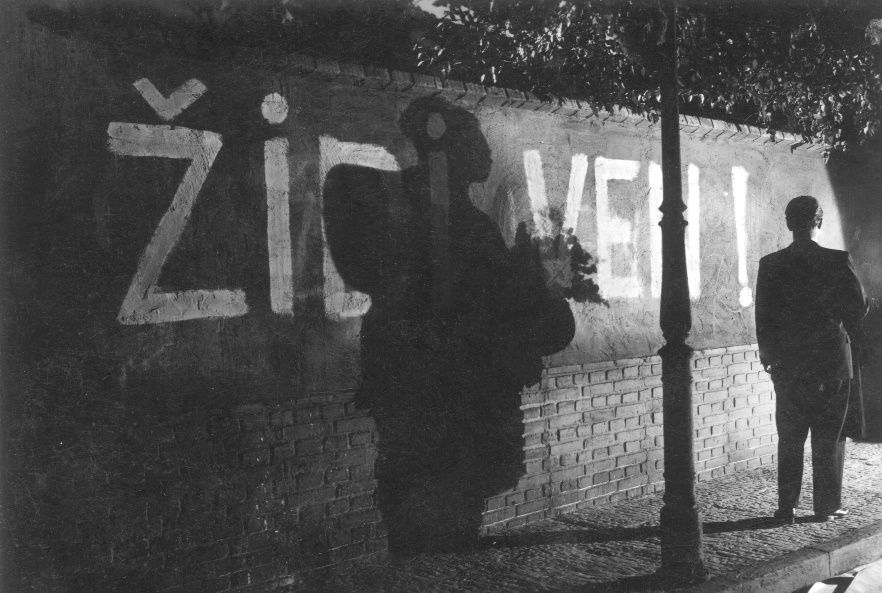

This motion picture depicts a broad range of subthemes related to the Holocaust. It portrays the rise of Nazism and growing anti-Semitism, as evidenced by signs that read “Jews out!”, “A purely Aryan business”, “Jews are not welcome in this shop”, and “No Jews or dogs allowed” and a newspaper headline that reads “No Jews allowed”. It also depicts the greediness of common people waiting for the Jews to be deported so that they could take their apartments, or at the very least, their furniture. (Neighbor: “And the sofa that Honzík used, is it staying here?”) It also deals with emigration to South America, the suicide of distraught Jews in a hopeless situation (Reiter), and the social downfall of mixed married couples (Toník, a former doctor, has to start working in a factory). The character of Hana also displays survivor’s guilt, as she lived, whereas the people closest to her left (and later perished).

Figure 2: Distant Journey: Signs in Prague’s streets announcing “Jews out!”. Source: National Film Archive Prague

The final scene, in which the Terezín ghetto is liberated by the Soviet army, lacks the pathos prominent in contemporary and later conventional films. Instead of a long line of tanks, just a motorcycle with a sidecar shows up in Terezín. Toník’s brother’s participation in the resistance and his hiding of a radio transmitter in his home, as well as Toník’s act of sabotage at a German arms factory, help flesh out the story. (Toník’s friend from the factory: “It was bad in the beginning, but now he’s already making good rejects.”)

The film also depicts traditional anti-Semitic stereotypes, such as the association between Jews and business: “Miss Kaufmannová, you can still practice medicine elsewhere, unless you want to do another job. For example some trading, Miss Kaufmannová.” At the beginning of the film, a religious autostereotype and heterostereotype is depicted. Hana’s mother asks her, “And you don’t mind the doctor is a Christian?” In the following shot, Toník’s father proclaims: “For me she’s a Jewess!”4 Hana herself does not prioritize her Jewishness; she feels like a Czech and has no thoughts of emigrating: “I belong just here, it’s my culture, language, people, everything.”

In Czechoslovak cinema, Jews are often depicted as absolutely positive characters. Radok tried to avoid this black-and-white view. Zdeněk, a family friend of the Kaufmanns and Hana’s admirer, gains a high position at Terezín, treats his fellow inmates harshly and arrogantly, and does not save Hana’s family from being sent to the East. The depiction of Czechs is also multifaceted. Besides the mentioned negative neighbor character (see p. 16), there is the positive character of a Czech gendarme in Terezín, who brings Hana a message from her parents and allows Toník to illegally enter Terezín. Toník’s fellow factory worker is also a positive character who wants to hide Hana so she does not have to go to Terezín.

The film’s esthetics are highly stylized; symbols play an important role. At the beginning of the film, the menorah represents the religious barrier between a Christian and a Jewess, whereas a globe evokes the free world. The bureaucratic and deportation machinery interweave in the striking keys of a typewriter, which, when viewed from the side, resembles a train. The ubiquitous numbers that appear in the storehouse containing confiscated Jewish property and on the rucksacks of deported Jews document anonymization. The piano is a substantial symbol; its tones accompany the film and its ruined frame in Terezín serves as a murder weapon on the one hand and on the other as a gong announcing freedom and the end of the war. The frequently repeated words transport and gas create the impression of a musical canon. The Star of David is a synecdoche of the Jews’ suffering and does not indicate pride in the lot of the Jews portrayed in later cinematic productions (see Romeo, Juliet and the Darkness, p. 25). After being liberated, Hana, in a close shot, demonstratively tears off the star.

The beginning and end of the film are framed by the voice of a subjective narrator (actor Václav Voska). At the beginning of the film, he translates German words praising the Reich in propaganda newsreels from this period. The narrator, with a tone and intensity in his voice, imbues the translation with a subjective viewpoint that sharply contrasts with the accompanying image. The narrator translates the aggressive rhetoric of the newsreel, the exclamations, the emphatic sentences, and the stirring words with sadness in his voice. The concluding “Long live Germany!” is uttered with a sigh. In the last scene, statistics about the Holocaust are summarized in names and numbers ironically: “Mankind has won. Auschwitz, Majdanek, Treblinka…”

The film consists of several layers. Nearly every sequence begins with a stylized documentary clip5, or a clip from Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda film Triumph of the Will (1935). Thus, a mosaic structure emerges that depicts both macrohistory (documentary clips) and microhistory (the fate of the Kaufmann and Bureš families). The documentary clips serve as a “narrative shortcut” and embed this fictional story into historical context, while also generalizing it. This type of framing captures anti-Semitism from above (in the newsreels) as well as from below (in the life of common people). It shows two parallel worlds: one in which Jews experienced the reality of the Nuremberg Laws, and who could not from a certain point in time visit cinemas and thus could not see these newsreels, and one in which non-Jews experienced this reality. Theatricality6 is an important layer of the film. It is manifested in the characters’ facial expressions and gestures, as well as in the spatial arrangement of the Terezín ghetto, which in some respects resembles a theatrical scenery. The ghetto is also visualized as a hopeless Kafkaesque7 labyrinth. The film employs a bold expressionist style to engender an emotional atmosphere (the semi-mad dance of the Jewish man in the storehouse among the light fixtures; the band in Terezín, whose music accompanies those being deported to the East; repeated shots of the gates of Terezín, from which people leave in one direction carrying coffins and through which in the other direction masses of new arrivals stream in).8

After Distant Journey, another Czechoslovak Holocaust motion picture would not be made for eleven years. The film “succumbed to an ideological curse and for a long time became a cautionary reminder for those who would have looked to it as an example” (Žalman 1993, 173). Distant Journey was ahead of its time by more than a decade and would become an important source of inspiration for filmmakers in the 1960s.9 One of the motifs in the film, which would be depicted later as well, was the complicity of many ordinary Czechs in the Holocaust.

1 The year and title given for each film have been taken from the Czechoslovak Film Database. See www.csfd.cz. Other information, such as the names of the screenwriters, have been taken from the books Český hraný film III-VI.