Полная версия

The Art of Dialogue

“When shall we three meet again In thunder, lightning, or in rain?” 8

In Pushkin:

“What do you think? Could I be recognised?” 9

Or in Chekhov

“Why are you always in black?” 10

The fact that it’s not a common question but a question which sets in motion the machine of dialogue means you will always hear it and feel it like an impulsive, germinating burst of energy. It is always experienced vividly, almost painfully. Disturbingly and joyfully, it includes you in the dialogue. Everything is in it – in the first question, just as the first step of a marathon contains the energy for the whole forty two kilometers and one hundred and ninety five meters.

In dialogue, there can be arsonist-questions which, like sparks, ignite first one question then another, until the whole theme is alight, the whole Person. The questions themselves aren’t powerful, not dangerous individually, as it were; they are just matches. Perhaps one does not even notice them. But together, – they give birth to flames. It is exactly this creative flame, which begins the process of the birth of the Individual, Adam. Notice how – with his quasi-innocent question “Where are you?” – God changes his conception of the living being-Person, created out of the dust of the earth, into a Person-individual, created out of questions and answers. Questions and answers – that is the main material from which the Person-individual is created: they torture us, fill us with hopelessness, reassure us, please and kill us; other questions are born – in brief, they make us living personalities. We were not simply thrown out of Heaven. No, we were condemned to a constant search for answers and the birth of new questions which are looking for their answers. An endless inner dialogue was started in us, with a constant insane search for answers in the labyrinth of questions. What is it? Why is this? What is it good for? To make you search. To search for your times, your place and your world. And most importantly to search for yourself, your Personality, your Wholeness. In life, it is this unending search for wholeness which makes a person into an individual. In theatre, it is this search which makes a character into a personnage. And one must understand the main movement of a dialogue as a search.

There is rarely only one question in dialogue. Normally there are many questions, and they often crash down on you one after the other, from different sides, like a hail storm from on high. So many questions but you don’t have time to answer? Well, you don’t need to. It’s not possible to predict their direction or to hide from them? Then, don’t do that. It’s frightening and at the same time, for some reason, also joyful? It’s an honest state of being. It is a crisis. It is a chaos from which everything wants to be born. If I see more and more questions turning up in a dialogue, then I know that the moment of crisis and revelation is getting closer. It’s for that reason you need the hail attack. Don’t be afraid. Only once you start to accept your defencelessness against these questions, as an essential condition for the moment of revelation, only then can you understand which direction you need to go in and why. And only then, somewhere deep down and very far away, an answer is born inside or outside of you.

For me, a reply is not yet the end of the question. Even with the reply – it’s not yet time to let the curtain down. It only seems as if – with a reply – one dialogue ends and you need search for the beginning of another. I don’t think that’s it. Perhaps there is basically only one dialogue? … which lives in us for the whole play, the whole role, our whole lives? That’s why I like long answers, long-lasting dialogues, even if they are interrupted for some time, but which don’t come to an end. Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko once spent sixteen hours in dialogue about the working principles of an Artistic theatre. The result? This marathon-dialogue gave birth to the great phenomenon of theatre culture, the Moscow Arts Theatre, the MChAT. That is dialogue. It’s the same in Dostoevsky’s novels: long questions and long replies. Remarkable.

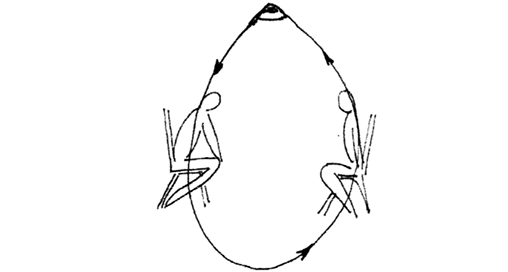

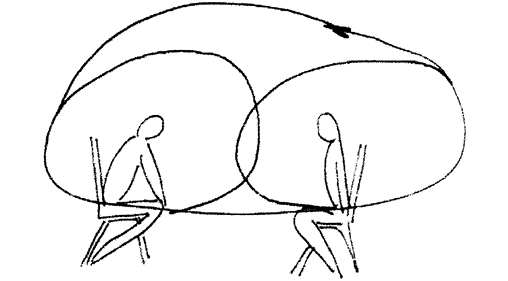

In plays, the dialogues are usually short, what a pity. Everything is unbelievably squeezed together. I feel this, and then I try to lengthen them out. One needs to give them time to live and be sorted through, and to compare the options, and time to search, to make mistakes and to doubt. Or I combine a few dialogues into one. I will speak about this more in the later chapter on “spherical dialogues” and introduce an exercise for this subject. Never mind that it’s in pieces, strewn throughout the play in chunks but, nevertheless, it’s one dialogue. This can happen: a dialogue began then suddenly got up and left, came back in the second act when nobody was expecting it, continued and unnoticed went off into town, returned after three years, in the winter, and again – the same dialogue. One dialogue, only one, a whole. I think that you can only reveal something genuinely unusual for yourself – the main and most important thing – in the unending development of the meaning in one and the same dialogue. Not in fits and starts, not in pieces, but whole.

There is a constant dialogue both in life and on stage. It goes over from one role to the other, from one performance to another of your performances. Look at the play, at your role, at all of your performed and produced plays, as at one journey. Not fractured but constant. Everything changes – different themes arise, all the possible situations; all the stops flash by, partners not resembling one another, sections of plays resonate, languages mix together; familiar and unfamiliar faces appear and disappear but in fact, it’s just one journey, one and the same, one and the same endless dialogue.

Of course, there are also short dialogues. And they can also be beautiful. Very beautiful. Small, but brilliant and quick dialogues. But nevertheless, I love long ones. It’s strange. When I was young, there was a lot of time but I loved short meetings then. And now time presses but I prefer longer ones. And I ask myself: “why?”

It happens, that a dialogue moves, and moves, floating along … how nice that you don’t want to think about how it will end.

How wonderful when dialogue ends with a question! It all started with a question and it will also end with a question. What does it mean? This means that dialogue isn’t finished – everything is still ahead. No full stop. Dialogue forever! Do you hear? In the very first question of the Lord God to us – “Where are you?”, the foundation is already laid for infinity. Did you hear it?! It is asked of us forever, and forever we are destined to search for its answer. I love to rehearse that sort of dialogue with actors. Well, the one where everything is clear in two or three replies, evokes only boredom in us actors, directors and the spectators. That isn’t a dialogue. At least, for me.

So, today, ten years after this Swedish seminar, I understand dialogue quite differently: Let there be a question in the beginning, but the answer …. Let the answer last for the whole dialogue, the whole role, the whole of life. Eternally. Only eternity lifts and changes a normal conversation to the level of a dialogue. Find this eternity in your dialogue. It can be hidden in each word, in each gesture, in each intonation. You can talk on different themes loftily, but still asking seriously and responding on a high level. You can think up different tricks and acting devices, include music and change the décor. But now a note of the eternal has made an appearance, with its own special sound, not resembling anything else, and you yourselves and everyone around you – Suddenly!!! they understand what this is not just answer-question, question-answer, it’s Dialogue.

7 Plato: Ion

8 Shakespeare: Macbeath

9 Pushkin: Don Juan

10 Chekhov: The Seagull

4. DIALOGUE? DISPUTE? CONVERSATION?

You must agree that not every dispute, conversation or just exchange of lines between two characters can be, or needs to be, defined as a dramatic dialogue. Inside the drama, all possible forms and types of communication between characters exist side-by-side. There can be monologues, conversations, disputes, and simple exchanges of phrases, different word games, double-entendres and so on. In other words, in one performance, in one role, there not only can, but there also should, be different forms of communication. This variety of forms, undoubtedly, enriches both the role and the performance. Now, it’s important to understand that one form can fluidly transform into another, as it moves forward. For example, a conversation can turn into a dialogue and vice versa. Use this boldly. Sometimes, it makes sense to also use the capacity of this structure for mutual-insertion, in other words, a dispute can live inside a dialogue, and a dialogue inside a dispute, in other words: one becomes the substantial part within the other. A monologue can find a place in a dialogue, and a dialogue in a monologue. One lives in the other – dialogue can live inside conversation with its own special life. This looks like a blob of oil floating in water without merging into it.

Some actors feel that they do not necessarily need to know all of these different forms but I advise them, with some insistence, to separate their methods of working on dialogue from their methods of working on short scenes or sketches. This are totally different analyses and a totally different actors’ position. Do not hurry to call each bit of pair work in a play a “dialogue”. As the saying goes – not all yogurts are equally useful!

This confusion begins right from the time spent inside the four walls of a theatre school, which then translates to work on stage. Even now, I come across the most simple first-year undergraduate scenes, made up of literally two or three replies, which the drama school teachers are calling dialogues, and in fact they are rehearsing them like simple skits. But these have completely different laws and rules – the work on dialogue and the work on a scene for two. Once in the theatre, actors continue to mistakenly think that they master the methods of working with dialogue. So, please take note – my advice is not to rush into saying it’s a dialogue every time two characters have a conversation. In fact, many communicative forms of interaction exist in plays, and they differ greatly from each other.

Coming across different types of interaction of characters on stage in the theory of theatre and in my pedagogical and directing work, I have tried to classify them. It turned out that each form of communication has its own working title. You should think of them exactly as they are: as “working” and not academic terms. Maybe the terms are not always accurate, and I myself do not completely agree with some, but it always helped me to understand how to work with one or other type of pair work in a scene. I think that one or another classification, which you can meet in literature, will help you not only to learn to distinguish dialogue from conversation, games or disputes, but also to make your own divisions of forms of on-stage communication, to define their different types and, using all of that as a starting point, create your own working methodology. Here are a few main types of communication which I have found in my old drama school notebook.

The battery

The point of this communication arises only in the context of two opponents. If there’s no opposition, it’s not working. The participants, who are exchanging points of view, somehow help each other. Their pair only exists because of their exchange and because they are together. Their communication reminds one of a battery. It will work only when there are two poles (+) and (-). The energy of such an interaction only arises when the whole sum of positions, opinions and knowledge is upheld by the two different “I”s.

This is how many dialogues in commedia dell’arte are constructed, for example, early character comedies: the servant and his master.

I plus I

This interaction, although it looks like a normal exchange of lines, nevertheless, it has different themes, different contexts, which are absolutely foreign to each other. That’s why in fact it isn’t a dialogue but the existence of its two participants in two different monologues.

For that we can find a lot of examples in Chekhov’s plays: one talks about means to fight balding while the other talks about the essence of human happiness.

In this type of interaction, there exists a higher “I”, which, has distributed lines among participants of the dialogue, in times and situations. For example, the playwright, who himself divided up the positions and leads the interactions the whole way. The participants have the function of executors but not creators. The centre of meaning does not rest on one of the participants of the dialogue but is placed higher than them – in the higher “I”.

An example of this are Plato’s dialogues and a number of plays of ancient dramaturgy.

An agreed game

This is when the participants have previously defined one main theme and one point of view on it. There are no differences of opinion between them, they voluntarily, according to a prior agreement, take up different positions for the game. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that they agree on what they are saying and standing up for. Their opinions can freely be swapped and muddled up between each other. In this way, they confuse the spectator, who has not guessed that they have agreed to this game, and they force the spectator himself to search for the truth. It’s not an argument, not a discussion, but an imitation of arguments and discussions, a game within a game.

Look at Molière’s comedies and Shakespeare. This game appears in the dialogues of Plato, too.

If the agreement is set up openly at the beginning of such a game, then the spectator will follow, with excitement, how this agreement is played out, and each actor follows where he and his partner is, at any given moment, relative to the agreement, how they can sharpen the game, how to spice it up. In other words, they follow to see which way the agreement is realised by the actors’ improvisations.

The duel

This is often not real dramatic action, but a verbal skirmish, a quick exchange of short phrases. Each waits for the other’s line before they can reply. The text which they speak is not as important as the shift in context which it brings. What’s important is the form of the reply – theatrical, literary – and the paradoxical nature of the question and answer.

Look at Oscar Wilde’s plays, for example, they have series of contextual explosions. The shorter the line, the more likely is the change of context. And that is of value here, first and foremost.

Gentleman’s discourse

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.