Полная версия

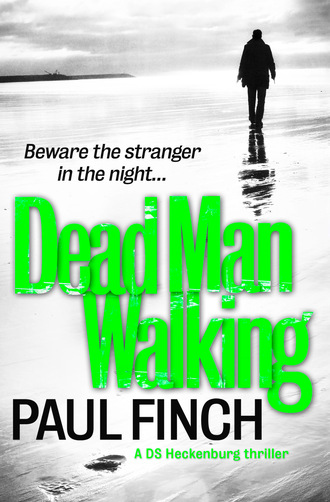

Dead Man Walking

‘East shore?’ Mary-Ellen asked, raising her voice over the engine.

‘Yeah, steady as you go though.’

‘Steady as I go.’ She cackled. ‘Aye aye, skip …’

‘You know what I bloody mean.’

Despite the potential seriousness of the situation, Mary-Ellen bawled with raucous laughter. ‘Only funning. Hey you’re my line-manager, Heck … I would never take the piss out of you for real!’

Mary-Ellen might only have been in the job four years, but she was a copper through and through. With a dark sense of humour and generally relaxed persona, she enjoyed her work and didn’t get fazed by its more onerous prospects. She had that all-important burning desire to ‘get up and at ’em!’, as she was fond of saying, and that was something Heck heartily approved of. You couldn’t play at being a copper; to be effective in the job, you had to fully absorb yourself in it. So many learned that on the first day. Those with sense got out quickly; those who hung on, looking constantly for inside work, only made life difficult for all the rest. Not so Mary-Ellen. Her previous beat, Richmond-upon-Thames, was pretty sedate by normal London standards, though it also encompassed both banks of the Thames and boasted over twenty miles of river frontage, so she was no stranger to pulling bodies out of the drink – which gave an additional explanation for her irreverent attitude now. That said, she was still unlikely to have scoured any body of water quite like this one.

Witch Cradle Tarn was the child of a geophysical fault long predating the glaciers that had broadened out the valley above; it was a cleft in the mountains formed by ancient tectonic forces, and for its size it was astonishingly deep – nearly seven hundred feet – and abysmally cold. Its sides shelved steeply away beneath the surface, but its eastern shore, which was almost flush against the cliff-face, was heaped with glacial scree, which intruded some distance into the water itself, creating semi-invisible shallows comprising multiple blades of rock, none of which were marked by buoys and any one of which could pass through the keel of a boat like a knife through the belly of a fish.

For several minutes they ploughed through turgid mist, Heck only sighting the surface of the tarn if he glanced over the gunwales, where it flowed past as smooth as darkened glass. The fog shifted in bizarre patterns and yet remained impenetrable. The quiet was unearthly. Even the drone of the engine was muffled, and yet whenever they spoke a word, it echoed and echoed.

‘You really thought you heard a shot last night?’ Mary-Ellen asked.

‘I dunno.’ Heck shrugged again. ‘Strange sounds in these mountains. I’ve only been here two and a half months, but I’ve already realised how deceptive things can be.’

‘Sure you weren’t dreaming?’

‘I can’t definitively rule that out, either.’

‘I can make some calls later, if you want,’ she said. ‘We’ve got a list of all licence-holders.’

‘Yeah, do that. Ask some searching questions – like what the hell they thought they were doing discharging firearms in the wee small hours. Go at them hard, M-E. Make it sound like we know they were up to something. Even if they were shooting rats in a barn or something, they’re unlikely to cough unless we press them, and we can’t dismiss them from any enquiry otherwise … unless we find something nasty out here of course, in which case it’s a whole new ball game.’

Heck didn’t hold out much hope for that, but they were now approaching the tarn’s eastern banks, so Mary-Ellen cut the engine and lifted the propeller, letting them drift inshore. There were no proper landing places on this side of the tarn, no quays, no jetties – in fact there were no paths or roads either, though it wasn’t impossible to explore this shore on foot. Further back from the water’s edge, pines grew through the scree, creating a narrow belt of woodland. This was just about visible as Mary-Ellen kept a steady course from north to south, the vague outlines of trees standing spectral in the mist.

‘Jane Dawson! Tara Cook!’ Heck said, putting the loudhailer to his lips. ‘This is the police … can you hear us?’

He waited thirty seconds for a response, but there was nothing. Without the engine, the silence was immense, broken only by the lapping of wavelets against the rocks.

‘Jane Dawson, Tara Cook!’ he hailed again. ‘This is the police. Can you respond please? Even if you’re injured and unable to speak … throw a stone, bang a piece of wood on another piece of wood. Anything.’

The lack of response was ear-pummelling.

‘Can you get us a tad closer inshore?’ Heck said.

‘I’ll try. Just be prepared for the worrying sound of grinding, cracking timbers.’

‘Don’t even joke about that.’

‘Who’s joking?’

They veered a few yards to port. Heck could clearly see the submerged juts and edges, like serrated teeth, no more than a couple of feet below the surface. Meanwhile, the rocks exposed along the waterline were piled on top of each other haphazardly and yet resembled those huge, manmade defences that guarded the entrances to Elizabethan-age harbours.

‘Okay, that’s far enough,’ he said, grabbing the boat-pole.

Mary-Ellen corrected their course. They continued to glide forward, veils of murk opening in front of them. The shore and its rows of regimented pine trunks was a little more visible, but not greatly so.

‘Perhaps start up the engine, eh?’ Heck said over his shoulder. ‘The noise might let them know we’re here.’

Mary-Ellen complied, while he hailed the girls another five times, always leaving thirty-second breaks in between. All they heard in response was the dull chug of the engine, until a few minutes had passed and this was subsumed by the rumble of churning water. Just ahead, the fog cleared around a protruding headland of vertical rock with a greenery-matted overhang about thirty feet above. Thanks to the heavy autumn rain, one of many temporary rivulets descending from the surrounding fells was pouring down over this in a minor cataract. The space beneath the overhang was filled with shadow. Heck directed his spotlight into it, just able to pick out a few clumps of shingle against the innermost wall. Normally, if memory served, there would be a small beach there, but the tarn’s high level had inundated it. Either way, no one was taking shelter.

They pressed on, the cataract falling behind them, its roar dwindling into the all-absorbing vapour. They’d now traversed a quarter of the tarn’s length.

‘Starting to think this is a long shot,’ Mary-Ellen said. ‘Couldn’t we be more use back at the nick, manning the phones?’

‘Let’s go down as far as the Race,’ Heck replied. ‘After that, we’ll come back … hang on, what’s that?’

Mary-Ellen stared where he was pointing, catching a glint of colour in the grey; a flash of orange. It could have been anything, a tangle of bobbing rubbish, a plastic shopping bag scrunched between two semi-submerged rocks – except that you didn’t as a rule find shopping bags or any other kind of rubbish in Witch Cradle Tarn, which normally was far beyond the reach of unconscientious slobs. Of course it could also have been a cagoule, and now they looked closely, they could distinguish a humanoid shape; two lengths of orange just below the surface (legs?), the main bulk of the orange (the torso?) above the water-level, thanks to the two boulders it was wedged between. When they drew even closer they saw that it wasn’t solely orange either, but spattered black and green by moss and dirt, and streaked with crimson – as was the third length of orange (an arm?) folded over the back of it.

‘Christ in a cartoon …’ Heck breathed. ‘They’re here! Or one of them is!’

Quickly, Mary-Ellen cut the engine again. ‘The anchor!’ she shouted.

He scrambled to the back of the craft, took the small anchor from the stern locker and threw it over the side, its chain rapidly unravelling. Other items of kit were also kept in the stern locker, including a zip-lock first-aid bag and two sets of rubberised overalls and boots, which the crew were supposed to don if they ever needed to wade out into deep water. There was no time now for a change of costume, but Heck grabbed the first-aid kit and moved to the gunwale, peering down. Heaped scree could still be discerned below. It wasn’t just jagged and sharp, it would be loose, slimy – ultra dangerous. But again, this was no time to start thinking about health and safety. Heck pulled on a pair of latex gloves, before zipping his phone inside the first-aid kit and then climbing over the gunwale and lowering himself down.

The tarn’s gelid grip was beyond cold, but now the adrenaline was pumping. Heck’s boots found a purchase about three feet under. Holding the kit above his head, he pushed himself carefully away from the craft, pivoted around and lurched towards shore. Behind him, he heard Mary-Ellen shouting into the radio, asking for supervision and medical support. It was a futile gesture – there was usually no radio up here, but it had to be worth trying. A second later there was a splash as she followed him over the side. They struggled forward for several yards, closing the distance between themselves and the body – but actually making contact with it wasn’t easy, as it was lodged at the far end of a narrow passage between rocks, the floor of which constantly shifted, threatening to collapse at either side, creating suction currents strong enough to pull a person under. To counter this, they clambered on the rocks along the edges, slick and greasy though these proved to be.

It was indeed a body, by the looks of it female, but in a woeful state: much more heavily bloodied than they’d seen from the boat, at first glance lying motionless and face-down in the water, its string-like fair hair swirling around its head. At the very least, its left arm, the one folded backward, was badly broken, while the other was concealed from view because the bedraggled form was wedged on its right side.

Heck leaned down, placing two fingers to the neck. It was ice-cold and clammy; there was no discernible pulse.

‘Shit,’ he muttered. He felt around under the face to check the nose and mouth were elevated from the water. Now that it was slopping and splashing, it covered them intermittently, but it hadn’t done this sufficiently to wash away a crust of congealed blood caking the nostrils and lips. Heck scraped what he could of that away, to free the air-passages. ‘I know it’s non-textbook,’ he said, ‘but we’ve got to move her from here right now. If we don’t, she’ll drown. You got a filter valve?’

‘In the first-aid kit,’ Mary-Ellen said. ‘Hang on, you’re saying she’s still alive?’

‘Dunno, but she was still bleeding when she washed up here. Here!’ He tossed his phone over to her.

‘Heck, there’s no signal …’

‘Never mind that, get a couple of quick shots – the body and the location where we found it. Every angle. Hurry.’ Mary-Ellen did as he asked. ‘Okay,’ he said. ‘We can’t drag her, so we’re going to have to lift. Take her legs.’

Mary-Ellen plunged into waist-deep water, and manoeuvring herself into place, wrapped her arms around the body’s thighs.

‘Try and keep her horizontal, okay?’ Heck said, sliding his own hands under the armpits, supporting the casualty’s head against his thigh. ‘Minimum twisting and turning. Her left arm’s bent the wrong way over her back – looks horrible, but it’s best to leave it that way.’

‘Yeah, yeah.’

‘Okay … three, two, one …’

The girl’s body lifted easily. She wasn’t particularly heavy. But on raising her above the water, Heck saw something that shook him. The cagoule fabric covering her front right shoulder had burst outward, along with tatters of the woollen and cotton layers worn underneath, and what looked like strands of muscle tissue. Below that was a crimson cavity, from out of which red-tinted lake-water gurgled.

‘Christ!’ he said. ‘I think … I think she’s been shot!’

‘What?’

He craned his neck to survey the back of the victim’s right shoulder, and spotted a coin-sized hole in a corresponding position.

‘She’s been shot from behind.’

Mary-Ellen had turned chalk-white. ‘You serious?’

‘Quick, get her to shore.’

They splashed through the shallows until they mounted a low, shingle embankment a few yards in front of the pines, and laid the lifeless form carefully down. Heck applied the sterile valve and they attempted resuscitation – to no effect. They persisted for several minutes longer, still to no effect. No matter how good a copper you were, unless you also held a medical degree, you weren’t qualified to pronounce death – but this girl was just about as dead as anyone Heck had ever seen. Aside from the gunshot wound, she’d been severely brutalised, suffering repeated contusions to face and skull. That didn’t necessarily mean she’d taken a beating; it might be in accordance with the girl having fallen. The only way down to the tarn from the east fells was via steep gullies and perilous slopes.

Either way, this was now a crime scene.

‘I shouldn’t really do this,’ Heck said, feeling carefully into the girl’s pockets, ‘but on this occasion, establishing ID is pretty vital.’ He extricated a small leather purse containing credit cards. The name on all of these was Tara Cook.

‘So where’s the other one?’ Mary-Ellen wondered, giving voice to Heck’s own thoughts. He glanced at the foggy woods. Thick veils of vapour hung between the trunks. Nothing moved, and there was no sound.

‘Jane Dawson!’ he shouted. His voice carried, but still there was no response.

‘We need to get up on the tops and have a look,’ Mary-Ellen said.

Heck disagreed. ‘Two of us? Covering all those miles of empty fells? In fog like this? Be the biggest waste of police time in history. Besides, this is now a murder scene. We need to preserve it, and start the investigation. We also need to alert the local population – we don’t know if this danger has passed yet.’

‘I hear all that, Heck, but the other girl’s still missing. We can’t just ignore her.’

Heck chewed his lip with indecision. That Tara Cook was dead, a clear victim of homicidal violence, did not bode well for the vanished Jane Dawson. But climbing the fells to look for her – just the two of them – would be a hopeless, pointless task even if there hadn’t been dense fog. To have any hope of getting a result in these conditions would require extensive search teams experienced in mountain rescue, not to mention dogs, aircraft, the lot. But Mary-Ellen was right about one thing – they couldn’t just do nothing about the missing girl.

‘Perhaps check along the shore,’ he said. ‘If Jane Dawson made it down to the tarn as well, she might still be alive.’

Mary-Ellen nodded and disappeared into the trees, while Heck tried his radio again as he stood alongside the corpse, but gained no response, not even a crackle of static. He spent ten minutes on this before finally turning to the trees and calling for Mary-Ellen.

Now she didn’t respond either. He called again.

The maximum depth of the east shore wood could only be fifty yards or so, before the gradient sharpened upward and the mountainous scree became too harsh for any vegetation to have taken root there. Of course, that didn’t mean she couldn’t have wandered for a significant distance to the north or south.

‘Mary-Ellen!’ he called again, advancing into the woodland gloom, not liking the way his voice bounced back from the cliff-face towering overhead.

Behind him, the glare of the outboard spotlight penetrated through the trees in a misty zebra-stripe pattern. He moved a few dozen yards north, trying to avoid clattering the loose debris with his feet. That Mary-Ellen hadn’t so much as called back to him was not reassuring. How far could she have ventured in ten minutes? As he sidled away from the boat, the murk thickened. Soon the stanchions of the pines were no more than upright shadows. He halted again to listen – and to wonder for the first time how it was that a female hiker had been shot while rambling in this wilderness, and who by.

‘Mary-Ellen!’ he called, pressing on a little further. At his rear, the glow of the boat’s spotlight had diminished to a ruddy smudge.

He listened again. An incredible silence. Even if the policewoman had been doing no more than mooching about, he’d surely hear her.

But could someone else have heard her too?

Had that person already heard her and taken appropriate action?

As Heck backtracked towards the boat, he tried to calculate how much time had elapsed between now and the gunshot he’d heard the night before. A glance at his watch showed that it was just before nine-fifteen. He’d been disturbed in bed at quarter past midnight or thereabouts. So, nine hours in total. More than enough time for the killer to have long left the area. Assuming he actually wanted to leave.

Heck bypassed the point where the boat was moored. The corpse of Tara Cook lay where they had left it.

It would be impossible to second-guess the killer’s next move, because they had no clue about motive. But just suppose the fatal shot had been fired somewhere much higher up – on Fiend’s Fell for example – and the body had fallen down the cliff-side. With the tarn down here to break the fall, how could the killer be sure the victim was dead? Wasn’t it at least conceivable he would try to get down here, to check out the scene for himself? Heck headed south along the shore, more cold, dark fog embracing him. Even if the killer had clambered down here, nine hours was more than enough to locate the corpse, establish death and high-tail it away again.

Again though, that question – what if he didn’t want to high-tail it?

And what about the other girl? Heck knew one thing for certain – he’d only heard a single shot. Then of course there was Mary-Ellen – where the hell was she?

He stopped again. In this direction, what looked like straight avenues lay between the ranks of waterside trees, though a little further ahead progress was impeded by several trunks that had fallen over. This wouldn’t have been completely unusual in a wood at the foot of a scree-cliff – heavy chunks of rock would occasionally fall, smashing and flattening the timber; but they made difficult obstacles. He climbed over the first diagonal trunk, and crawled underneath the second, increasingly suspecting that Mary-Ellen would not have gone to so much trouble to make a quick, cursory inspection of the shoreline. Beyond the fallen pines, the woods seemed to close in, the rising ground on the left steepening, and on the right falling away towards the tarn’s edge. Heck veered in the latter direction until he was virtually on the waterline. As before, the smooth surface rolled away from him, flat as a mirror, black as smoke. At this time of year there wasn’t a plop or plink; neither frog, newt nor fish to disturb the peace.

Further progress was impossible in these conditions, he concluded.

He turned back, but it was as he stooped to clamber underneath the first fallen tree that he heard the whisper.

If it was a whisper.

It could have been the wind sighing through meshed evergreen boughs. That was entirely possible too. But it had sounded like a whisper.

Heck whirled around, unable to see very much of anything, until …

Had that been a faint, dark shape that had just stepped out of sight about twenty yards away on his left? Heck’s heartbeat accelerated; his scalp prickled.

Suddenly it seemed like a very bad idea to be here on his own, especially as this character was armed. He set off forward, moving parallel with the tarn, heading back in the direction of the boat, eyes fixed on the spot where he thought he’d spied movement. And now he heard a sound behind him – a snap, as though a fallen branch had been stepped on. He twirled around again, straining his eyes to penetrate the vapour, unable to distinguish anything. When he turned back to the front, someone in dark clothes was standing nearby, leaning against a tree-trunk.

At first Heck went cold – but just as quickly he relaxed again.

Recognising Mary-Ellen, he walked forward. For some reason she’d removed her luminous coat. To lay over a second body maybe? Except that these days you weren’t supposed to do that. And now, having advanced a few yards, he saw that he wasn’t approaching Mary-Ellen after all. A bundle of interwoven twigs and bark hung down alongside the trunk. The outline they formed was vaguely human, but was mainly an optical illusion, enhanced by a shaft of light diffusing through the wood from the boat and exposing the place where the bark had fallen, which had created the impression of a face.

Heck heard another whisper.

This time there was no doubt about it.

He glanced right. It had come from somewhere in the direction of the upward slope. Ten seconds later, it seemed to be answered by a second whisper, this time from behind, though this second one had been less like a whisper and more like a snicker – a hoarse, guttural snicker. Heck gazed into the vapour as he pivoted around, wondering in bewilderment if all this could be his imagination.

For a few seconds, there was no further sound. He took several wary steps towards the upward slope, the rank autumnal foliage opening to admit him – and then closing again. Needle-footed ants scurried across his skin as the fog seemed to thicken, wrapping itself around him, melding tightly to his form. For a heart-stopping second he had the overwhelming sensation that someone else was really very close indeed, perhaps no more than a foot away, watching him silently and yet rendered completely invisible. Heck turned circles as he blundered, fists clenched to his chest, boxer fashion. He wanted to call out, but his throat was too dry to make sounds.

More alert than he’d ever been in his life, Heck backtracked in the direction of the waterline; this at least was possible owing to the slant of the ground. When he got there, he pivoted slowly around – to find someone directly alongside him.

‘Coast appears to be clear, sarge,’ Mary-Ellen said.

Heck did his best to conceal his shock – though he still almost jumped out of his skin. ‘What the … Jesus wept!’

‘What’s the matter with you?’

‘Creep up on me, why don’t you!’

‘Sorry … heard you clumping around. I presumed you heard me.’

‘Well, I bloody didn’t!’

‘Getting jumpy in your old age, or what?’

‘Don’t give me that bollocks. Why didn’t you reply when I shouted?’

‘Sorry.’ Mary-Ellen shrugged. ‘Never heard you.’

‘Hmmm. Suppose these acoustics are all over the place,’ he grunted. They trudged back to the boat. ‘You didn’t hear anything else, though? No one farting around?’

‘Farting around?’

‘Whispering … chuckling.’

She looked fascinated. ‘For real?’

‘Shit, I don’t know.’ He glanced back into the opaque gloom. ‘More atmospheric weirdness, maybe. Or the local wildlife. The main thing is there’s no second corpse?’

‘Didn’t find one.’

‘Well we can’t get any help up here to do a proper pattern-search until this weather clears.’

They’d emerged onto the bank, back into the glare of the outboard’s spotlight. Tara Cook lay as before. Heck angled back towards her, and knelt. He didn’t want to disturb the scene more than he already had and would avoid making further contact if possible, but it had belatedly occurred to him to check for any lividity marks, maybe even signs of rigor mortis, as either of those could give a clearer indication how long the girl had been dead. He reached down towards her and suddenly the body twitched. Heck froze. For several helpless seconds he knelt rigid, as, without warning, the ‘corpse’ reached a violently shuddering hand towards his face, and drew five carmine finger-trails down his cheek. Still, neither he nor Mary-Ellen were able to respond.

Tara Cook’s head now lolled onto her shoulder. Her puffy eyes were still swollen closed, but slowly, almost imperceptibly, she opened her mouth. A low moan surged out, along with globs of fresh blood, which spattered down the front of her filthy cagoule.