Полная версия

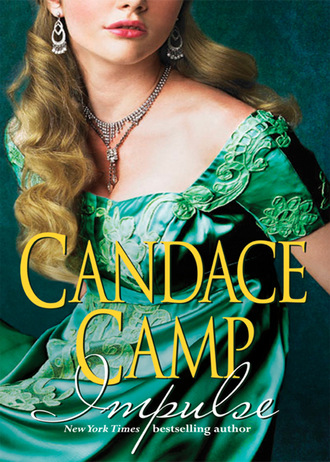

Impulse

“Jeremy?”

She started toward the main staircase, then stopped as an old yellow dog, his coat liberally shot through with gray, came hobbling up to greet her. “Hello, old fellow,” she cooed, bending down to pet him. “I’m sorry we ran off without you today. It was just too long and difficult for you.”

The look in his old eyes was wise and dignified. Angela curled an arm around his neck and gave him a hug. Wellington was her oldest pet, almost fifteen years old now, and, if the truth be known, still her favorite deep in her heart. It always hurt her to leave him behind. However, it was just as painful, if not more so, to see him struggling to keep up and always falling behind, and if they went far, he simply could not make it.

At that moment, an orange cat came daintily down the banister of the stairs and made the short leap onto Angela’s shoulder. It draped itself with familiarity around her neck. Angela went up the stairs, her collection of animals following her, and along the hall to the drawing room her grandmother preferred. Along the way, another cat joined the group, this one a fat gray Persian with a face so flat that Jeremy said it looked as if it had walked into a door.

The two dowager Lady Bridburys, both her mother and grandmother, were in the drawing room, her mother half reclining on a fainting couch and her grandmother sitting ramrod-straight near the fire. The elder Lady Bridbury let out an inelegant snort at the sight of Angela surrounded by her animals.

“Honestly, Angela, people are going to start saying you’re odd if you persist in walking about with that entire menagerie.” She lifted her lorgnette and focused on Trey. “Especially when some of them are so … different.”

“No, they will simply say that they fit me perfectly. Everyone already thinks I’m odd, you know.” She crossed the room and gave the old lady a peck on the cheek in greeting, then turned toward her mother. “Hello, Mama. How are you this afternoon?”

“Not well,” her mother replied in a die-away voice. “But, then, I am rather accustomed to it. One learns to adjust.”

“I should think you would be accustomed to it,” Angela’s grandmother, Margaret, commented. “You are never well.”

Laura, the younger Lady Bridbury, assumed a faintly martyred look, her usual expression around her mother-in-law, and said proudly, “Yes, I do not enjoy good health. But, then, it was always so with the Babbages.”

“Pack of weaklings.” Margaret dismissed them contemptuously. “Thank God the Stanhopes don’t suffer from such nonsense. I did not have so much as a chill all winter.”

Laura gave her mother-in-law a rather pitying look. She had known the dowager countess for almost thirty-five years now, and she still was unable to understand why the woman took so much pride in her robust condition. In her own opinion, a woman ought to be suffering from something most of the time; otherwise, she would never get enough attention from the male members of her family.

However, Laura knew it was useless to try to make Lady Bridbury understand any point of view other than her own, so she turned back to her daughter. “Have you been out walking, my dear? You should wrap up. You might catch a chill. I know it is April, but the wind, you know, can be so dangerous. You should wear a muffler.”

Angela’s grandmother rolled her eyes, but Angela merely smiled at her mother and replied, “Doubtless you are right, Mama.”

She kissed her on the cheek as well, and nodded toward Miss Monkbury, her grandmother’s self-effacing companion, who sat away from the fire, knitting. Miss Monkbury gave an odd ducking nod in reply and continued to knit. Angela sat down between her mother and grandmother, saying, “Did Jeremy come home? I saw the carriage outside.”

“Yes. And he brought a decidedly peculiar young man with him,” Margaret answered. “An American.”

“An American? I wasn’t aware that Jeremy even knew anyone from America.”

“One doesn’t, normally,” Laura agreed.

“That is one of the things that is so odd about his coming here. A Mr. Pettigrew, Jeremy said he was. Jason Pettigrew. I ask you, what sort of name is that? Sounds like a commoner, but then, I suppose all Americans are, aren’t they? He looks like a solicitor, but when I told him so, he denied it.” Her frown seemed to indicate that she suspected he had lied to her.

“I found him rather shy,” Laura put in. It was rare that her opinion on any matter agreed with her mother-in-law, though she never disagreed directly. “Of course, he does speak in that American way, but other than that, he seemed quite gentlemanly.”

“Yes, but what is he doing here? That is the question, Laura,” Margaret put in impatiently. “Not whether he is polite.”

“But what is Jeremy doing here, either?” Angela asked. She, of course, lived at Bridbury year-round, and had for four years now, ever since the divorce and its attendant scandal. But Jeremy and his wife spent most of their time in London.

“That is what I asked him,” Margaret assured her. “But he would not tell me. He said he had to talk it over with you first.” She looked affronted.

“With me?” Angela was astonished. She loved her brother, and owed him a great deal for what he had done for her over the past few years. They had a pleasant relationship. But she could not imagine anything that he would want to discuss with her before he would discuss it with their grandmother. Angela was well aware that her position in the family was the least important of anyone’s, except perhaps Miss Monkbury’s.

“Yes. Apparently this Mr. Pettigrew is to be a part of the discussion, also. He and Jeremy retired to the library. I have rarely been quite so astonished. However, I find that the present generation is so often graceless.” She sighed.

Angela stared at her. “Mr. Pettigrew? But why?”

“I just told you, I haven’t the slightest notion,” her grandmother replied acidly. “I was not taken into your brother’s confidence. You had best go to the library and ask him yourself. However, do, please, go up to your room and change into something a trifle more presentable first.”

“Yes, Grandmama, of course.” It was useless to point out that if Jeremy was waiting for her, her grandmother might have told her so when she first came into the room. She stood up, saying, “If you will excuse me, Grandmama. Mama.”

“Of course, dear child,” her mother responded, sniffing her lavender-scented handkerchief, obviously suffering another of her weak spells. Her grandmother gave Angela a peremptory nod.

“And, Angela!” Margaret called out as she neared the door. “For goodness’ sake, leave those animals behind. You cannot meet this American person looking like a zookeeper.”

“Yes, Grandmama. Perhaps I should leave the dogs here.”

Her grandmother raised a single icy brow at this sally and waved her out of the room.

Angela walked down the long gallery that stretched across the front of the house and into the west wing, where the bedrooms lay. She found her maid, Kate, waiting for her in her room. Kate already had one of Angela’s better dresses, a dark green velvet, spread out on the bed, and a pair of slippers to match it waiting at the foot of the bed.

It did not surprise Angela that her personal maid was well aware that Angela was to join her brother and their surprise guest. In fact, she would not have been astonished if Kate knew why Jeremy had come to Bridbury. There was nothing as swift or as efficient as the servants’ grapevine.

Kate, a woman much the same age as Angela, with laughing brown eyes, a wealth of chestnut hair and a buxom figure, jumped up from the chair when Angela entered and hurried over to her, clicking her tongue admonishingly. “Where in the world have you been? You look like half the county is clinging to your skirts. Out drawing them pictures again, eh?”

“Yes, I have to confess that I was.” Angela glanced down at her skirts, a little surprised to find that several burrs and a few sticks, as well as dust and pieces of dried grass, were clinging to the hem of her dress. “I was hoping to find some flowers out already, but I could find nothing but lichen on the rocks.”

“Well, if it isn’t flowers, it’s birds, or some kind of berry bush or something.” Kate shook her head. “I’ll tell you the truth, my lady, I can’t fathom what you see in them little flowers, growing in cracks and such, looking more like a weed than anything else.”

“They intrigue me—so secret and hidden. It’s like finding a prize when you do spot something unique. And they’re lovely. Simple and delicate. Besides, it gives me something to do.”

“Well, selling your pictures to them journals and magazines and such, that makes sense, to make a little money.”

“Yes.” Angela loved the flowers and shrubs and birds, and loved just as much to draw her pencil sketches and watercolors of them, but it was nice to be able to sell a few from time to time to periodicals and books. It gave her pin money, which saved her from having to depend on Jeremy for absolutely everything. She had lost her inheritance, of course, when she left Dunstan; the dowry she had taken with her into the marriage had stayed with him. She did not regret losing it; she never would. But it was hard, having to live on another’s kindness, even her brother’s.

Kate had been undoing the row of tiny buttons down Angela’s back and helping her out of her dress as she talked. Now she held out the green dress for Angela, still chattering away merrily. Kate was allowed far more liberties than the typical maid. She had taken on the job of Angela’s personal maid when both of them were in their teens, and the two of them had been close from the start. Kate had gone with Angela when she married Lord Dunstan years ago, and their bond had been forged into hardened steel during the ordeal of those years. It had been Kate who helped Angela find the courage to leave Dunstan and then accompanied her when she stole out of the house in the dead of night. For that brave loyalty, Angela loved Kate almost like a sister. Since the divorce, her other friends, even close ones like her cousin Cee-Cee, had absented themselves from her life. Kate was now Angela’s only confidante, her most valued friend, and it was only at Kate’s insistence that she continued to serve as Angela’s personal maid. Angela had asked her to remain at Bridbury as her companion.

Kate had turned down the offer. “A companion, miss? Nay, that’s only for a gentlewoman. I couldn’t be content with that, now could I? I need something to do, and not stitching little embroidery, neither. ‘Sides, I like making my own money and not living off someone else’s charity. It’s like slavery, I think, like selling yourself, just for the sake of being able to be genteel-like. But I ain’t genteel, and never will be. I’d sooner sweat and have my independence.”

“Have you seen the Yank that’s with His Lordship?” Kate was asking now, as she knelt and began to unbutton Angela’s shoes.

“No, I haven’t. Have you?”

“Aye, I did. I carried some of his bags up. Just to see what he looked like, you know, and maybe get an idea who he was.” She giggled. “When I carried them into the room, he was already there and had taken off his shirt. He looked that surprised to see me. I knocked, and he said to come in, but I guess he was expecting one of the footmen. Ned and Samuel were carrying the trunks. His jaw dropped open, and he blushed bright red. Then he started scrambling to put his shirt back on. He’d dropped it on the floor, and he had to pick it up, but then he put his arm in the wrong sleeve, and he couldn’t get it on. He kept jerking it and twisting, that loose arm flapping around like some crazed bird. It was all I could do not to burst out laughing. I guess I got a better look at him than I would ever have expected.”

Angela couldn’t help but smile. “Poor man. I am sure you did nothing to ease him.”

“Of course I did. I curtsied and asked if he wanted me to unpack his bags, trying to act like there was nothing wrong. But he kept apologizing to me.” She shook her head in amazement.

“Well, he is American. Perhaps he’s not used to castles and servants and such.”

“More like he’s not used to girls,” Kate retorted. “He’s got a prim-and-proper look to him, so stiff you think he might break if he tried to bend over. And plain dressed. Not badly dressed, just … so very severe. All the other girls think he’s dead handsome. I thought him only all right, if you like that sort of pasty look of a man who spends his life indoors. Me, I like a man with a little meat and muscle.” She grinned. “Gives you something to hold on to, you know.”

Angela shook her head in mock despair. Kate was an inveterate flirt, and Angela was sure that she had broken more than one poor man’s heart. But she liked to talk as if she were a wilder sort than she was, primarily, Angela thought, to entertain her.

“Did you find out why he’s here?” she asked as Kate finished with her shoes and rose to take a critical look at the overall effect.

“No. Dead mum about it, His Lordship’s man is, which I’m thinking means he doesn’t know. All I know is, Ned said later that he caught a glimpse into one of the bags, and it had a powerful lot of important-looking papers in it.”

“A solicitor, perhaps. Or a man of business. I wonder what he has to do with Jeremy,” Angela murmured. “Even more, what could it have to do with me? Well, I suppose the only way I shall find out is to go down there.”

But Kate would not let her leave until she had fussed with her hair a bit, pinning in the strands that had come loose during Angela’s walk. “There, now you look beautiful.”

Angela barely glanced at her image in the mirror. It had been many years since she fussed over her looks. All she cared about was appearing neat and ordinary. The latter was a difficult task for a woman with hair the color of burnished copper, she had found, but over the years she had made blending in an art form. She wore subdued colors and plain styles, and her hair was always done in a simple bun worn low upon her neck. She never wore any jewelry, except perhaps for a cameo brooch at her throat. Even her hands were without adornment, the nails clipped short and no rings upon her fingers.

She walked down to the library and knocked softly on the door. Jeremy answered, bidding her enter. When she stepped inside, Jeremy rose to his feet, as did the man who was sitting in the wingback chair across from him. Angela cast a quick, curious glance at the other man, noting that he was, as Kate had told her, not bad-looking, but perhaps a trifle rigid.

“Angela.” Jeremy smiled and went over to her to kiss her lightly on the cheek. “You look in health.”

“As do you. This is a pleasant surprise.”

“Not so pleasant for Grandmama, I believe.” He smiled. “I thought she might eat me for arriving unannounced.”

“Is Rosemary with you?” Angela asked as her brother led her toward the chairs.

“No. Couldn’t expect Rosemary to leave London during the Season.” He stopped in front of his guest. “Angela, I’d like you to meet Mr. Pettigrew.”

The man in question bowed stiffly to her, and they exchanged greetings. Almost immediately Pettigrew excused himself, saying that he was sure the Earl would wish to talk to his sister alone. Angela waited politely until the young man had left the room, then turned to her brother, eyebrows going up.

“Jeremy … what in the world is going on? What are you doing here in the middle of the Season? And who is that young man?”

“An American. An assistant to another American—whose name I don’t know,” he added darkly.

“But what has it to do with me? Grandmama said you wished to see me.”

“It has a great deal to do with you. Well, with all of us, but you are the one who—” He stopped and sighed. “I’m sorry. I am telling this all muddled. I have been in such a state recently … it’s a wonder I can make any sense at all. Here, sit down, and I shall start all over.”

They sat down in the leather wingback chairs, facing one another, and Jeremy, taking a deep breath, plunged into his story. “It started, oh, I’m not sure, a year or two ago. Someone bought a portion of my share of the tin mines. We needed to repair the house in the city, and somehow Rosemary and I seemed to have an inordinate amount of expenses as well, and, anyway, I sold a goodly block, I’d say about ten percent of the mine. Then, just this last year, I sold another portion of it, not that much. At the time, Niblett brought it to my attention that someone had bought others’ shares in the mine. You know, Aunt Constance had owned a part, and then it was split among her children when she died, and all of them sold their shares. There had been several sales like that. I thought it odd. Niblett didn’t want me to sell any more, but I couldn’t see any harm. It was not the same person who had bought the first amount I had sold, or so I thought, and the others had been sold to still other companies and people. So I sold another chunk, almost ten percent again. But three or four weeks ago, well, Niblett got this letter. It seems that a company in the United States claimed that it owned a—a majority of the mine. It turns out that Wainbridge—Grandfather’s friend, you remember him, don’t you?—had sold this company his fifteen percent. And Tremont—that’s the name of the American company—owned all the other bits and pieces that had been sold over the years, too, including both the ones I had sold.”

Angela gazed at him for a moment, assimilating the information. Finally she said, “You mean that this American company actually controls our mine now?”

Jeremy nodded, looking miserable. “I’m sorry, Angela. I don’t know how it happened. Even Niblett was surprised. He knew there had been some activity, but he did not know that it was all being bought by the same company.”

“Is it so very bad? I mean, I understand that you are getting less money than before, but that would have happened even if different people had bought from you.”

“Yes, but Tremont now has control over the decisions. I do not. It can do whatever it wants with the mine.”

“I see. So if they make poor decisions, you will suffer.”

“We will all suffer.”

Angela was well aware that this was true. She was completely dependent upon her brother, and her mother and grandmother largely were, also. Whatever wealth the Stanhopes had, had passed to Jeremy.

“Of course. But is it so bleak? We cannot assume they will make bad decisions, can we?”

“According to the letter, they intend to close the mine.”

Angela gaped at him. “What? You can’t be serious!”

He nodded vigorously. “I am. I couldn’t believe it, either, at first. But this week Mr. Pettigrew showed up in London. I’ve been meeting with him and Niblett and my solicitor. It is worse than bad. It’s. Oh, God, Angela, this American practically owns me!”

“Mr. Pettigrew?” Angela’s voice rang with disbelief. “But he seems so mild….”

“No, not him. Though he is not so mild when you are dealing with him in business. But I am talking about the company that bought the mine. It is owned by some American. I don’t know who. I haven’t met the man. Mr. Pettigrew is merely his representative, and he refuses to say who the principal is.”

“But, Jeremy, this doesn’t make any sense. Why would anyone buy a mine only to close it down?”

“I don’t know! That’s what I argued. Pettigrew said that the mine simply was not producing enough. He showed me all these figures demonstrating how its production had gone down over recent years. Of course it has. That’s precisely why everyone was so willing to sell to Tremont. He went on and on about how we had been taking everything out of the mine and not putting anything back in. He talked about all the improvements that needed to be done to make the mine profitable again, though we had not used the profits to do so. We just took them out and spent them. You can’t imagine how lowering it was to have to sit there and hear him point out how foolish I had been, all in that quiet, prim way. Of course, Niblett had said the same thing to me time and again, but I had never done what he advised. You know me. I never have had a head for business. I assumed that Niblett was just complaining. And, besides, we were always desperate for money. You know how it’s been with us. Rosemary’s money wasn’t enough to save us, and after—” He stopped, red flaring up in his cheeks. “Well, that is, you know, we simply haven’t had the money.”

“I know.” Angela looked down at her hands in her lap. She knew what he had been thinking but had stopped himself from saying. Angela was the reason that they had not had the money. When she fled Dunstan, she had lost his money for the Stanhopes, and in that way she had failed her family, finally and enormously. It was to Jeremy’s credit that he had never thrown that up to her. He had never even tried to convince her to go back to Dunstan.

“Anyway, Pettigrew said that they had considered making those improvements, putting money into the mine so that the profits would be greater. But he said that they had decided that they did not have enough—connection was the word he used—to make that great an investment.”

“What did he mean?”

“I didn’t know. I asked him, but he didn’t answer. Instead, he pulled out a number of papers—notes and deeds. He had the deed to that piece of land that Grandfather sold to Squire Mayfield before he died, as well as the hunting cottage I sold two years ago. I sold it to an Englishman, but apparently he was merely a solicitor buying the cottage for someone else, an American. Last year Squire Mayfield sold his plot to the same man, as well.”

“The same one who owns the mine? But, Jeremy, who is this man? Why is he buying so much of our property?”

“Apparently he is obsessed with the English nobility. That’s the only thing I can think of. It is all so bizarre. He must be excessively wealthy, and I assume he is trying to—to buy his way into Society. I am not sure what his reasons are. Pettigrew would not explain it, really. He is quite polite, but you cannot pry anything out of him that he does not want to say. Believe me, I tried all the way up here from London. But he would just start talking about the scenery or asking questions about the estate.”

“But why did this man choose you to buy these things from? And how can closing down a mine and buying property in England make him a part of Society?”

“I can only assume that the Stanhopes must have been an obvious choice—titled and desperately in need of money. Besides, we have the other main requirement.”

He stopped and eyed his sister a little uneasily. Angela looked up at him. “What is that?”

“A female of marriageable age and condition in the family.”

Angela froze, staring at her brother mutely. She felt as if all the air had been knocked from her lungs.

When she said nothing, Jeremy went on hurriedly. “That is the plan, apparently. He wants to marry into the British nobility. I presume he must realize that no matter how much land he might buy or how much wealth he might have, he would never be accepted. So he wants to marry a daughter or sister of an earl or a viscount or.” He trailed off miserably, sneaking a glance at Angela’s stricken face. “I am sorry, Angie. You don’t know how sorry I am that he should have chosen to fix on this family.”

“Oh, he chose well, all right,” Angela said bitterly. “A family with a daughter so disgraced that they could not hope for any better marriage for her. One they would be happy to sacrifice for a little money.”

She jumped to her feet and began to pace agitatedly, her hands clenched into fists at her side. “I won’t do it, Jeremy! You cannot ask this of me. Our grandfather already sacrificed me once for money for the family. You cannot ask me to do it a second time!”

Jeremy rose and went to her, reaching out to touch her shoulders. She flinched away from him, and he sighed. “I wish there were some other way, Angela. I talked to Pettigrew until I was ready to drop. I pleaded and argued and pointed out the unfairness of it. He apologized and flushed and looked perfectly miserable, but he would not budge. He is not the one who makes the decisions. He is merely representing someone else.”