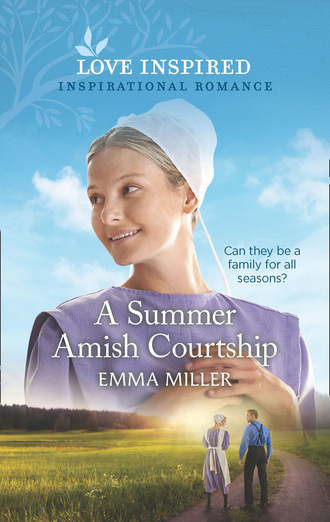

A Summer Amish Courtship

“Oh, my! It’s that handsome schoolmaster!” June declared, clapping her hands. She pushed open the screen door and walked out onto the back porch, leaving the door wide open.

“The schoolmaster?” Immediately concerned, Abigail dropped the wooden spoon she’d been using to stir the apple butter onto the counter. It fell so hard that it bounced. “What’s he doing here?” She glanced at the round, black-and-white battery-powered clock on the kitchen wall. It was only two forty-five. School wasn’t out for another fifteen minutes.

Abigail hustled to the open back door, her heart fluttering in her chest. It had to be Jamie. Was he ill? Had he been injured? She fought the panic rising in her chest as she went down the porch steps and into the driveway, walking past her mother.

“Schoolteacher!” June greeted, waving eagerly. “So glad you could stop by. Come in for coffee and apple streusel! My daughter makes a fine streusel!”

“Mam, shush,” Abigail murmured. “It’s not proper calling out to a man like that.”

Now that the buggy was closer, Abigail could see that it was indeed the schoolmaster. And her Jamie. She could see her little boy through the buggy’s windshield. He didn’t look ill, or injured, but why else would the teacher be bringing him home in his buggy? And early, no less.

Abigail hurried out into the middle of the driveway, catching the pretty mare’s halter as the buggy rolled to a stop. Boots barked and ran in circles around the conveyance.

Abigail went straightaway to the passenger’s side and slid open the door. “Jamie? Are you all right?” she asked, trying as best she could to hide her alarm. “What’s wrong, sohn?” She reached out to him to take him in her arms. He was really too big for her to carry anymore, or even hold in her lap. And he didn’t like it. But Jamie was her baby boy, her only child. A mother couldn’t be criticized for caring about her child, could she?

“I’m all right,” Jamie said, pushing his mother away. “I’m fine. I can get down myself.”

Abigail clasped his cheeks between her hands, looking into his brown eyes. He looked fine. Not sick at all. “Not hurt?” she asked.

“Not hurt or sick,” the schoolmaster said dryly, pulling the brake on the buggy.

His name was Ethan Miller. Abigail had met him several times. They were part of the same church district. The schoolmaster had also stopped by the house a couple of times as he walked home from school—to complain about her son’s behavior. She didn’t care for Ethan Miller. He was grumpy and he expected too much of Jamie too soon. The poor boy had just moved halfway across the country. His life had been turned upside down like an apple cart: leaving his friends in Wisconsin, living with his grandparents, joining a new community. Who could expect there wouldn’t be a few bumps in the road?

The schoolmaster got out of the buggy and walked around to Abigail. He was a tall man, slender, with blond hair, brown eyes and a carefully trimmed beard. Some might have thought him handsome, and maybe in other circumstances, she might have, too.

The border collie sniffed at the schoolmaster’s heels and then wandered away.

“I brought Jamie home because we had a problem at school today,” the schoolmaster said. “Again.”

Abigail looked down at her son who was now standing beside her. “Go into the house with your grossmami,” she told him, stroking his shoulder. “She’ll find you a snack.”

Jamie smiled up at her. “Ya, Mam.”

“I’m not making him a snack, Babby,” her mother put in. She was standing on the far side of the driveway, but she had heard every word. Abigail’s father was losing his hearing but her mother’s was as good as her own and it seemed as if she never missed a thing. “Jamie’s been naughty. I don’t make snacks for naughty boys.”

The schoolmaster glanced June’s way and then returned his gaze to Abigail. “Actually, I’d like Jamie to stay here. And tell you for himself what he did.”

Abigail looked at her son, then at the schoolmaster. “I don’t understand.”

When the teacher didn’t say anything, she turned her stare back to Jamie. “What did you do?”

“I didn’t mean to, Mam,” Jamie said, pouting. “I’m very hungry. Could I have my snack?”

“Tell her,” the schoolmaster said, using a tone of voice that Abigail didn’t much care for. Who did he think he was, speaking to a young boy so harshly?

“Please, Mam?” Jamie whined. “I’m so hungry.” He touched his forehead. “I’m feeling dizzy.”

“Tell her,” the schoolmaster repeated, lowering his voice until it was little more than a rumble.

“Tell her, you naughty boy!” June called from the other side of the driveway.

Jamie’s eyes filled with tears. “I tried to tip over the girls’ outhouse. I just wanted to see if I could do it.” The words tumbled out of his mouth. “I was trying to use a lever. Like Grossdadi taught me. I didn’t know Elsie was inside! I didn’t want to hurt anyone.”

Abigail’s eyes widened. “You tried to tip over an outhouse? With someone inside?”

He grabbed the hem of her apron. “I didn’t mean to, Mam!”

“There, there,” Abigail soothed, stroking his blond curly head. “It’s all right.”

“It’s not all right,” the schoolmaster said. Now he was taking on a tone with her. “It was dangerous, what he did. Then he lied to me and when he finally did admit what he’d done, he wasn’t even apologetic.”

“I am sorry, Mam! I am,” her son cried into her apron.

“He says he sorry,” Abigail returned stiffly, meeting the schoolmaster’s gaze.

“He’s not sorry he did it. He’s sorry he got caught.” The schoolmaster brought his hand to his neatly trimmed beard and stroked it. “And that’s not good enough, Abigail.”

“Oh it isn’t, Ethan? For whom?” She let go of Jamie to take a step closer to the schoolmaster. Her irritation was rising by the second. Her father had always said her quick temper was her worst trait, but sometimes she thought maybe it was her best. Life had been hard as a single woman since her husband’s death and it had been her experience that sometimes standing up to men got things done when nothing else would.

“That’s bad, tipping over outhouses,” June put in from the far side of the driveway.

Ethan stood there in front of Abigail for a moment. He glanced away, then back at her. Maybe he had realized that she wasn’t a weak-minded woman who could be pushed around by any man who wanted to give her advice on how to raise her son.

“This is the fourth time I’ve had to speak with you about Jamie’s behavior at school,” Ethan intoned, “and I’m ready to just ex—” He took a breath and glanced at her son. “Go with your grandmother,” he said quietly.

Jamie took off for the house and Ethan met Abigail’s gaze.

For some reason, his soft tone made her angrier than if he had just raised his voice to her. And who did he think he was to be ordering her son around after school hours? “You’re ready to just what?” she demanded.

“Expel him,” he answered flatly.

“Expel? Expel him?” Abigail sputtered.

“In my day, boys were paddled,” June called. “That’s what my dat did when my brothers were bad. A good switching is what this boy needs, Babby.”

Abigail whipped around to her mother. “Mam, please see to your grandson. Inside.” She turned back to the schoolmaster.

“You’ve left me with little other choice. If Jamie’s behavior doesn’t improve, he’s out,” Ethan said. “I’ve asked you repeatedly to rein your son in and so far, I’ve seen no improvement. He doesn’t turn in his schoolwork, or when he does it’s not complete. He doesn’t listen,” Ethan said, ticking off on his fingers. “He’s disruptive, disrespectful and out of control.”

“Out of control? He’s nine years old!” Abigail pointed toward the house in the direction Jamie had just gone. “And what does that say of you, Ethan?” She placed her hands on her hips. “A teacher who can’t control one little mischievous boy?”

“Mischievous?” Ethan flared. “Ne, his behavior is beyond mischievous. What about last week when he cut the strings off Martha’s prayer kapp with scissors? What of the cow pie he put in Johnny Fisher’s bologna sandwich? What about—”

“You know what I have a mind to do, Ethan Miller,” Abigail interrupted, gritting her teeth.

Ethan rested his hands on his hips. “What?” he demanded.

“I have a mind to go to the school board and have you dismissed.”

He laughed, which made her even angrier. If that was possible.

“Dismissed under what grounds?” Ethan scoffed.

“On your lack of control in the classroom,” she told him. She folded her arms over her chest. “What kind of teacher are you that little boys can get away with such things? It’s clear to me that you are unable to control your students and that…that you should be replaced immediately because you—” she pointed at him “—are obviously not doing your job.”

“My job is not to teach your child how to behave.” He pointed back at her. “That is your job. It’s obvious the boy needs discipline at home.”

Abigail drew back, dropping her arms to her sides. Somewhere in the very back of her mind, she knew he had a point, but he had made her so angry that she couldn’t think straight.

Ethan walked away. “Get your son under control or I’m expelling him,” he warned.

“I certainly hope you don’t speak to your wife with that tone,” she flung back at him.

Without another word, the schoolmaster got into his buggy, turned around in the driveway and headed out the way he’d come. Abigail watched him until he was halfway down the lane and then marched toward the house. Who did Ethan Miller think he was? How dare he threaten to expel her son! She passed her mother who was still standing there beside the driveway.

June watched her daughter walk by. “What do you think of the schoolteacher, Babby?” she asked brightly. “Me?” She broke into a broad smile, not giving Abigail a chance to respond. “I like him.”

Chapter Two

Ethan took his time seeing to Butterscotch, leading her to the water trough and then giving her a good brushing until her coat gleamed. Afterward, he fed her a scoop of oats and set her loose in the pasture to graze until sunset when he’d put her up in the barn for the night. He knew it was foolish, but the time he spent with the mare made him feel closer to his wife, more than five years gone now. Closer to her in memory at least. How she’d loved the mare, their little farm in upstate New York, their quiet life. How she had loved him.

He’d been so lost after her unexpected death that he thought he might die of his grief. He didn’t, of course, just as his wise father had predicted. And as the days turned into months, then years, though he hadn’t stopped loving her, the pain was no longer so sharp. Now, after so much time had passed, more often than not, he smiled when he thought her, rather than cried.

Ethan stood beside the gate and watched Butterscotch wander off to graze in a bed of fresh, flowering clover. Then, his hands deep in his pockets, he walked down the lane toward the harness shop in search of his father. He was still mulling over his conversation with Abigail Stolz. He was hoping to talk with his father about Jamie and the boy’s mother. Maybe he could offer a different perspective.

Ethan took his time walking, taking in the two-hundred-acre farm, its fields that were now turning green, white fencing, barns and outbuildings. In the two years since the family had moved to Hickory Grove from New York, Millers’ shop had flourished. Despite the local competition of Troyer’s just three miles away, his father had found ways to provide goods and services to both Amish and Englisher customers. Not only did he repair and make nearly any kind of leatherwork, but he also sold the type of supplies a man with livestock needed: liniments, wormers, fly and pest control traps and sprays, you name it. And that wasn’t all he was selling these days.

A year ago, Ethan’s stepsister Bay Laurel, who they called Bay, had started selling jams and jellies, fresh eggs, preserves, and baked goods. Her single shelf had turned into an entire aisle and his father was considering expanding the size of the store to keep up with the women’s side of the business. Then there was Ethan’s brother Joshua, newly wed, who had built a greenhouse over the winter and was about to open a business selling seedlings, flowers and vegetable plants.

All that, and Benjamin, his father, was still dreaming of expanding his business inside the huge dairy barn he’d remodeled. He wanted to go into buggy making. Ethan wasn’t much for working in the harness shop. That was why he had taken the job of schoolmaster when the position had become vacant. But buggy making was quickly becoming a passion of his. He still had a lot to learn, but he liked using his hands to make a wheel, a door, a padded seat. Alone in the shop, or even working beside his father, he loved the peacefulness of it. No little girls squirming in their seats, no little boys bringing toads into the schoolhouse. No Jamie Stoltz trying to tip over an outhouse.

Ethan’s annoyance with the boy came back in a single breath. Which turned to near anger toward the mother. He felt sorry for Abigail, a widow alone trying to raise a boy without a father, but surely she understood that it was her duty to control the boy’s behavior. Ethan couldn’t help thinking that if Jamie was bad at school, it was likely he wasn’t all that well behaved at home either. He got that impression from the grandmother. He couldn’t remember her name, though they’d been introduced at church. Daniel King, Abigail’s father, and his wife had been in the harness shop a couple of times and they’d bumped into each other at a dinner celebrating Epiphany back in January. That was just before Abigail and her son had arrived in Hickory Grove. He had heard from his stepsister Ginger that she was widowed three or four years ago, though Ginger hadn’t known any of the details. That fact alone gave him good reason not to judge the woman so quickly, but—

“Ethan? You okay?”

He looked up. He’d been so lost in his thoughts that he hadn’t seen or even heard his sister-in-law, Phoebe, approaching.

“I thought you were going to walk right by me.” She met his gaze with a smile. She was wearing a blue scarf tied around her head and the denim coat one of his stepsisters had commandeered. Ordinarily, Amish women didn’t wear men’s denim barn coats, even around their house, but there was nothing ordinary about his stepmother’s girls. Or his brother Joshua’s new wife.

“Uh, sorry, just thinking. Ya, I’m fine,” he said. He liked Phoebe. She’d come from a hard life, bringing a little boy with her, but she’d managed to make a new life there in Hickory Grove. She was sweet and kind and fun, but the thing Ethan liked most about her was her resilience. He admired her ability to see beyond her troubles and find the goodness in the world God provided. He was beginning to think maybe he needed to take a page from her book. As much as he hated to admit that his father and stepmother, Rosemary, were right, it was time to move on with his life. He knew it was what his Mary would want. But he just… So far, he just hadn’t been able to get there.

“Been down to the mailbox,” Phoebe said. She held up a bundle of flyers and envelopes. “Something here for you. A bank statement, I think.” She stopped in front of him, sifting through the pile in her arms. With a family their size—his father and stepmother, his stepsisters, stepbrothers, and brothers still living at home, as well as Phoebe and her son—they numbered fifteen at the supper table. And that was if his stepsister Lovey and her family didn’t join them. They received a lot of mail.

“It’s here somewhere,” she said, still thumbing through the stack.

“Just leave it on the counter,” he told her, turning so he was still facing her, backing down the driveway, hands deep in his pants pockets. “Have you seen my dat?”

“In the shop. In the back, I think. I stopped to see Ginger on the way to the mailbox. She’s working the register.”

He nodded, turned and continued on his way.

“See you for supper,” Phoebe called after him.

His back now to her, he raised his hand in response.

Ethan found Ginger occupied at the register ringing up an English woman. “My dat?”

She nodded over her shoulder as she dropped fly paper into a brown paper bag. “Back in the buggy shop, I think. UPS delivered leather for seat covers.”

Ethan went through the swinging half door to get behind the counter, then through the next door and into the leather workshop. He nodded to his brother Jacob who was busy with an awl punching holes in what looked to be a new bridle he was making. Beside him, seated on a stool, was their eleven-year-old stepbrother, Jesse, who was talking a mile a minute about a bass in their pond he was set on catching.

Ethan walked through the shop and into a hall where the newly constructed walls had drywall but no paint yet. Doorway cuts in the walls led to empty space now that could be turned into additional workrooms or an office if his father wanted to expand later. At the end of the hall, he found the door to the buggy shop open.

Benjamin Miller’s door was always open, figuratively and literally, and not just to his wife and children and stepchildren, but to his community, as well. He was a good listener, but he also didn’t hesitate to give his opinion if it was asked. His father was the wisest man Ethan knew and even though he had just had his thirty-third birthday, he was still young enough to need his father’s guidance occasionally. Old enough to know it.

Benjamin turned on the stool where he sat at his workbench and peered over the glasses he wore for up close work. “Get that stovepipe?”

Ethan shook his head. “Didn’t make it to Byler’s. Had a problem with one of my students. Had to take him home. I’ll go get the stovepipe tomorrow.”

“Whenever you get to it will be fine.” Benjamin looked up at his eldest son, reading glasses perched on his nose. In his fifties, he was a heavyset man with a reddish beard that was going gray, a square chin and a broad nose. Ethan had his father’s brown eyes, but his mother’s tall, slender frame.

“I’m hoping this break in the weather means we won’t be needing to light that old woodstove ’til fall,” his father went on, nodding in the direction of the stove they’d recently installed. His father had traded a new full harness for the stove with a man from over in Rose Valley. Benjamin liked bartering and did it whenever he could. He said it reminded him of his childhood back in Canada where he’d grown up. In those days, he said, paper money was rarely exchanged; a checking account was unheard of. The sizable Amish community relied mostly on themselves and traded for everything.

Benjamin turned back to the piece of paper he was studying on his workbench: a sketch of the buggy he and Ethan were building together. It was a small, open buggy, referred to sometimes as a courting buggy. “You said you had a problem with a student. Get it worked out?”

Ethan took a deep breath. He sighed, removed his wide-brimmed straw hat and ran his fingers through his blond hair. His gaze settled on the box on the cement floor that had been opened to reveal yards of leather they would use to upholster the new buggy’s seat. “Ne… Well, maybe. I don’t know.”

Benjamin removed his glasses. “Want to talk about it?”

Ethan sighed again, and then the whole story just came out. It wasn’t the first time he’d talked to his father about Jamie. He knew the boy had been a problem since he’d arrived at school, but still, he listened patiently, commenting or urging Ethan on as he relayed the most recent incident.

When Ethan was done, he dropped down on a stool near the door. “I’ve just had it, Dat. I’ve half a mind to—” He halted and then started again. “I’ve half a mind to resign, effective the end of the school year. If I give the school board notice now, they’ll have time to find another teacher by September.”

“That what you want to do? Quit teaching?”

Ethan set his hat on his knee, studying the courting buggy that was nearly complete. The project was so close to being done that Benjamin was already working on the plans for a more traditional family-sized buggy. “I don’t know, Dat. I’m thinking maybe there’s some truth to what Abigail said. Maybe I’m not cut from the cloth of a schoolmaster.”

“Not sure I agree with that. Other folks in Hickory Grove would say you’re the best teacher they’ve had for their children. Last Saturday over at the mill, John Fisher was talking about inviting some other Amish teachers—men and women—to our schoolhouse for a day for you to run some kind of training. To get teachers together to talk about ways to teach our children about the world we live in these days. It’s not like in my day when we were isolated from Englishers. Insulated. No denying that as the world has changed, we’ve been forced to change. But that doesn’t mean we have to give up who we are. That means we’ve got to deal with the changes not just in our homes and our church, but our schools, too. Men like you, you understand that. You understand how hard it can be for our children. To hear the music, see the behavior and not covet it.”

Ethan worried his lower lip, thinking. Everything his father said was true. Teaching school wasn’t easy, not with Amish kids being exposed to Englishers: the clothes, the cars, the behavior. You couldn’t keep young folks on the farm all the time so they had to know how to deal with the world they were supposed to stand apart from. He knew they needed to be guided in how to stay on the path their ancestors had set out for them and school was one of the places they could find that guidance.

What Ethan didn’t know was if he was really the one to be doing it.

“That said,” his father went on, “if you do decide teaching isn’t your calling, you know you can join me here.” He gestured to the workshop they were both proud of. “Before you know it, Levi will be home and we’ll be getting serious about production.”

Over the winter they’d added an overhead door in the shop big enough to accommodate a buggy, and they purchased quite a few tools. A buggy maker had to be a welder, an upholsterer, a carpenter, mechanic and painter all rolled into one and he needed different tools for each aspect of the construction. Ethan’s brother Levi was staying with friends in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, apprenticing as a buggy maker. His plan was to learn what he could over the next year or so and then return to Hickory Grove. At least that’s why he said he’d moved to Lancaster, though Ethan suspected it was the larger population of single women that had attracted him to accept the position.

Ethan eyed his father. “You think we’re ready to go into business, do you? So far, we’ve just made that new family buggy for ourselves and the one for Lovey and Marshall.”

“And your courting buggy is nearly done.” Benjamin smiled, pointing at the sleek black buggy that took up the center of the shop.

Ethan shook his head. “Not mine. Will and Levi would get more use of it. Jacob. Before you know, Jesse will be taking girls home from singings.”

Benjamin hesitated. “I know you don’t want to hear this—”

Ethan held up his hand. “Dat—”

“I know you don’t want to hear it but I’m going to say it anyway.” He got off his stool and walked toward Ethan. “Because it’s my duty as your father to say things you don’t want to hear.”

Ethan rose, clamping his hat down on his head.

“It’s time for you to marry again, sohn.”

Ethan shook his head, surprised by the emotion that rose up in his throat, threatening to prevent him from speaking. He took a moment. “Dat,” he said when he found his voice. “We’ve been over this a hundred times. I don’t know that I’ll marry again.” He stared at a spot on the floor, embarrassed by the feelings welling up in him. His father was never one to tell his sons it was wrong to show emotion. Benjamin Miller was an emotional man, Ethan’s brother Joshua, too. But Ethan wasn’t like them. He didn’t know what to do with his sadness, his loneliness, except tamp it down, close it off, stay one step ahead of it.