Полная версия

The Firm

Charles’s one obligation as Prince of Wales and heir to the throne was to perpetuate the House of Windsor. He could have chosen to do nothing with his life while his mother reigned, to make no contribution to the welfare of the country. He could have squandered his income from the Duchy of Cornwall, hunted three days a week, played polo all summer, gambled, partied and drunk himself into a stupor. None of that would have mattered, in theory at least, provided he produced a legitimate heir.

For that he needed a wife and that was more problematic. By the time Charles was old enough to be looking for a suitable candidate in the 1970s, a sexual revolution had taken place in Western society. The contraceptive pill had removed the fear of unwanted pregnancy; we had had the swinging sixties, the age of rock and roll, the Beatles, flower power, free love and the beginning of women’s emancipation. Educated, well-bred women no longer saw marriage as their only goal in life, they went to university rather than finishing school, were independent, capable, smart, and when they married they were no longer prepared to keep house, mind the children and be decorative adjuncts to their husbands. Mrs Thatcher, after all, was about to become Britain’s first woman Prime Minister. Debutantes had had their day; virgins over the age of sixteen were becoming as rare as hens’ teeth.

Yet when Charles and Diana became engaged in 1981, the system – society, the press – still insisted that the Prince of Wales should marry a virgin – nearly twenty years after virginity had ceased to be of importance for the rest of society. And in a piece of advice that owed more to his generation than his personal wisdom, Lord Mountbatten reinforced the need.

‘I believe,’ he wrote to Charles, ‘in a case like yours, the man should sow his wild oats and have as many affairs as he can before settling down, but for a wife he should choose a suitable, attractive and sweet-charactered girl before she has met anyone else she might fall for … I think it is disturbing for women to have experiences if they have to remain on a pedestal after marriage.’

And to help with the sowing of the wild oats, Mountbatten made Broadlands, his house in Hampshire, available to the Prince as a safe hideaway to which he could bring girlfriends, away from the prying lenses of the press for which would-be-princess spotting had become an obsession. One or two of those girlfriends might have made perfect wives for the Prince. Several shared his sporting interests or his Goonish sense of humour and were good friends as well as lovers; they were intelligent, pretty, good company and from suitably aristocratic families. But any ‘past’ always ruled them out as possible brides. Camilla Parker Bowles, or Camilla Shand as she then was, fell into that category. But she pre-empted the problem by marrying Andrew Parker Bowles and in the process dealt a devastating blow to the Prince of Wales. Charles had been very young when that happened; he had met and fallen very much in love with Camilla in the autumn of 1972 when he was almost twenty-four and newly in the Navy. She was a year older and already seeing Andrew Parker Bowles (who was wonderful but hopelessly unfaithful). Her dalliance with Charles was a bit of fun – a brief fling while Andrew was posted in Germany – and it was destined never to go anywhere. She knew that she would not have passed the virginity test and had no desire to be a princess. The man she wanted to marry was her handsome Cavalry officer.

Four years later the Prince fell for another girl, Davina Sheffield, who could have been the soulmate he was searching for. She seemed ideal in so many ways, and they appeared to be very much in love, but she already had a boyfriend when Charles met her, an Old Harrovian and powerboat racer called James Beard. Davina initially rebuffed invitations to have dinner with the Prince, but he was so persistent that she eventually succumbed and the boyfriend soon fell by the wayside. He was subsequently conned into talking about his relationship with Davina by what turned out to be a Sunday tabloid reporter and the story of their affair, complete with photographs of their ‘love nest’, made headline news. It killed the relationship stone dead.

That was not the only time a girlfriend’s past was raked over, but the strong message girls took from all of this was that, unless you wanted the third degree from the tabloids, Prince Charles was not the man to date. By the same token, if your public profile needed a bit of a hike, in the case of actresses and starlets, he was your man.

Unsurprisingly Charles became despondent about ever finding the perfect girl and sought refuge with a number of married women, one of whom was Camilla Parker Bowles. Meanwhile, the press continued to link him romantically with just about every eligible girl he had ever shaken hands with, and went so far as to announce his engagement to one, Princess Marie Astrid of Luxembourg, whom he had never even met. The pressure was almost intolerable and he began to think that no girl in her right mind would ever want to be involved with him, far less marry into the House of Windsor. So when he met Diana in 1979, and found her to be so fresh, funny and delightful, as well as suitably aristocratic, and at just seventeen, suitably innocent, he began thinking of her as a potential wife.

They had first met two years before when Diana was still a schoolgirl and, in his eyes, jolly and fun, but nothing more than the little sister of his current girlfriend, Lady Sarah Spencer. Two years later, when that relationship had ended, they met again and although still very young in some respects, she had surprising maturity in others and clearly seemed to adore him. They had a number of casual meetings, never dates, always with others; and then sitting on a hay bale in the summer of 1980 she had touched him deeply. They were at a barbecue near Petworth, in Sussex, and he mentioned the murder of Mountbatten. She either had compassion that was way beyond her years or knew precisely which button to press. She said how sad he had looked at the funeral in Westminster Abbey; how she had sensed his loneliness and his need for someone to care for him.

Later that summer she went to stay with her eldest sister, Jane, married to Robert Fellowes, the Queen’s Private Secretary, at their cottage on the Balmoral estate; his infatuation deepened and everyone in the household fell in love with her. That autumn he invited her to a house party at Balmoral, after the Queen had left, to see what his friends thought. They were bowled over. As Patty Palmer-Tomkinson said to Jonathan Dimbleby:

We went stalking together, we got hot, we got tired, she fell into a bog, she got covered in mud, laughed her head off, got puce in the face, hair glued to her forehead because it was pouring with rain … she was a sort of wonderful English schoolgirl who was game for anything, naturally young but sweet and clearly determined and enthusiastic about him, very much wanted him.

Imagine his surprise, therefore, when after their engagement she seemed suddenly to hate everything he had thought she loved. He was quite at a loss to understand the change in Diana and thought it must be his fault in some way; that the prospect of marrying him was all too ghastly. And yet he spoke to no one about his anxieties; and when concerned friends tried to talk to him, he refused to listen. Pulling out would have been unimaginable: the humiliation, the hurt, the headlines, the castigation; but in retrospect, it would have been infinitely less painful and less damaging to everyone involved, including the monarchy, than going through with a wedding that he knew was a mistake. At the very least he should have discussed it. As one relation says, ‘In his position he bloody well should have spoken to people because he had to think of the constitutional side as well as the private side. He had chosen Diana with both sides in mind, but equally he needed to think of the consequences for both if it was going to go wrong.’

The trouble is that the Prince of Wales is fundamentally a weak man, and that is what has so incensed the Duke of Edinburgh over the years. He wanted a son in his own image – a tough, abrasive, plain-talking, unemotional man’s man – but those qualities bypassed his first son and settled instead on his daughter. Charles has a generous heart, he cares hugely about the underdog, because, for all his palatial living, he is one, he identifies. He wants passionately to make the world a better place, to stop people feeling hopeless and helpless, to stop modernizers from destroying our heritage, chemicals from destroying our environment, ignorance and greed from destroying our planet, red tape from destroying our lives. He is admirable in so many ways, but he has never been a strong character and has never been able to cope with confrontation. Blisteringly angry at times, certainly, demanding, yes, and on the sporting field no one could question his courage, but he has never been brave when it comes to taking tough decisions. He gets others to do it for him. Perhaps it is because he has always been surrounded by strong women: his grandmother, his mother, his sister – even his nanny. Helen Lightbody was such a terrifying woman that the Queen kept out of the nursery while she was in charge. By the time the Queen had the two younger children Helen Lightbody had gone and Mabel Anderson, her deputy and a much easier character, was in charge, and she and the Queen were good friends and brought the children up together. As a result the Queen had much more contact with Andrew and Edward than she ever had with Charles and Anne, and is still infinitely closer to them today.

In marrying Diana, for all her emotional turmoil and frailty Charles had found himself with another strong, determined woman. He didn’t understand her rages – one day during their honeymoon, when they were staying at Craigowan Lodge, a small house on the Balmoral estate, she lost her temper and went for him with a knife which she then used to cut herself, leaving blood everywhere. That night as he knelt down to say his prayers – as he regularly does – Diana hit him over the head with the family bible. He has never been to the house since. He just couldn’t fathom the emotional rollercoaster, the demands, the insecurities; he couldn’t cope, needed others to help, which of course infuriated her more. Michael Colborne was the first of a long string of members of the Prince’s staff who had to mediate with Diana while Charles backed away. Even during the honeymoon he was summoned to Balmoral to talk to Diana because she was so bitterly unhappy. She was already caught in the grips of an eating disorder, bored by the countryside, made miserable by the rain and baffled by the Prince’s desire to spend his days shooting and fishing. And what was he doing while Colborne spent more than seven hours with Diana while she raged, cried, brooded in silence, ranted and kicked the furniture by turns? He was out stalking with his friends.

That night both men were taking the train back to London; the Prince had an engagement in the south, Diana was staying at Balmoral. As Colborne waited in the dark by the car, a brand-new Range Rover, he could hear a fearsome row going on inside. Suddenly the door flew open and Charles shouted ‘Michael’ and hurled something at him, which by the grace of God he caught before it was lost in the gravel. It was Diana’s wedding ring; she had lost so much weight it needed to be made smaller. The Prince was in a black rage all the way to the train; the new car wasn’t quite as he had specified and so he took it out on Colborne, calling him every name under the sun. Exhausted and defeated by his day with Diana, Colborne simply stared out of the window and let the abuse wash over him. Once on the train, the Prince summoned him. Colborne had just ordered himself a triple gin and was in no hurry to respond. The Prince offered him another. ‘Tonight, Michael,’ he said, ‘you displayed the best traditions of the silent service. You didn’t say a word.’

And for the next five hours or more they sat together and talked about the Prince’s marriage; not yet two months old it was already a disaster. He was mystified by Diana’s behaviour, simply couldn’t fathom what was going on or what he could do to make her well and happy.

NINE

Not Waving: Drowning

It was never the case that Charles didn’t care. Couldn’t cope, yes; and as the months and then the years went by with no let-up from the unpredictability of Diana’s behaviour, he became hardened and at times downright callous in his attitude towards her. He had found her a top psychiatrist; he had done what he could to appease her. He had cut out of his life the friends she disliked or of whom she was suspicious; good, loyal friends, some of them friends since childhood – and, in typical style, he took the easy way out and did it without telling them. They were left to wonder what had happened when phone calls, letters and invitations to Highgrove and Balmoral simply stopped. He even gave away his faithful old Labrador Harvey because Diana thought he was smelly. None of this seemed to make any difference; and when she burst into tears or launched into a tantrum, nothing he could say seemed to calm her. So he gave up. When she made dramatic gestures he walked away, when she self-harmed he walked away. Not because he didn’t care but because he couldn’t help; he felt desperate, hopeless and guilty and to this day he feels a terrible sense of failure for not having been able to make his marriage work.

That is not to say that there was no happiness. There were moments of intense pleasure, the children brought huge joy and there was laughter and jokes and fun, but not enough to counter the difficulties, and as time went by the gulf between them became no longer bridgeable.

Diana had needs that Charles couldn’t begin to address. Anyone who has lived with someone suffering from an eating disorder (which was very probably in Diana’s case a symptom of a personality disorder and therefore even more complex) knows all too well what an impossible situation he was in. Anorexia and bulimia test and sometimes destroy even the most stable relationships and balanced homes. And all that we know of her behaviour – from her staff, her friends and even her family – fits every description that has ever been written about the disorders. The Prince didn’t stand a chance. And yet to outsiders Diana looked like the happiest, most equable girl you could hope to find. She seduced everyone with her charm and coquettishness, men fell like ninepins, she was playful and funny and oh so beautiful, so young, so glamorous. Just what the Royal Family needed to invigorate it and make it seem relevant to swathes of young people who didn’t see the point of it. She captured the hearts and minds of the nation. No wonder no one wanted to believe that behind closed doors Diana was deceitful, demanding and manipulative, and that the laughter was replaced by tears and tantrums. Much easier to believe that it was all a story put about by the Prince’s friends to discredit Diana. And when Diana accused him of doing as much herself, because the woman he really loved was Camilla Parker Bowles, there was nothing more to be said. Nothing would convince the majority of the British people that Charles was anything other than a villain who used Diana as a brood mare to produce the heir and spare he needed; that their marriage was a sham from the start and the woman he really loved, and continued to bed throughout, was Camilla.

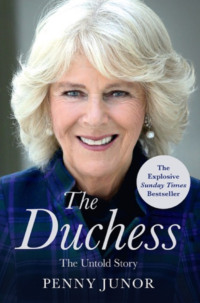

Camilla Parker Bowles has seen a turnaround in her fortunes since Diana died. Having been arch-villain and probably the most hated woman in Britain for a good chunk of the 1990s, people now rather admire her. They have bought into a touching love story. Charles was a bastard for what he did to Diana, so the script goes, but this is a woman he has loved since he was twenty-three. They missed their opportunity to marry then, but the flame still burned bright and now, in middle age, they have finally found happiness together. It doesn’t alter their view of what Charles did to Diana, but Diana has now been dead for nearly eight years, Camilla has behaved with dignity and discretion throughout, he has been true to her (if not to Diana), he’s a pretty decent chap in every other respect: they deserve some happiness.

It’s neat but it’s not the truth, and it is important to state this if only for the sake of William and Harry, who must infer from this version of events that the father they love used, abused and destroyed the mother they also loved. He did not and the impression of their marriage that Diana left on the world, via Andrew Morton and Panorama, and repeatedly rehearsed in documentaries, is grievously unfair.

The Prince of Wales has plenty of shortcomings but he is not a liar; his great misfortune is that he has never been able to be even faintly economical with the truth. There are so many occasions when the smallest, whitest lie would have saved him a great deal of trouble – starting with that fateful answer on the day of his engagement to Diana about whether he was in love. It has come back to haunt him regularly, as for many years did his admission that he talked to plants. And when I interviewed him in 1986 and asked him whether having a wife to talk to who had done ordinary, everyday things before her marriage was an advantage in helping him know how the other half lives, he said he didn’t really talk to Diana about that sort of thing, but conversations with Laurens van der Post were very stimulating from that point of view. His Private Secretary, Sir John Riddell, almost visibly clutched his head in his hands. But the most disastrous example was during his television interview with Jonathan Dimbleby when he was asked about his infidelity. The question didn’t come out of the blue, and his reply was very well thought out.

‘Were you,’ asked Dimbleby, ‘… did you try to be faithful and honourable to your wife when you took the vow of marriage?’

‘Yes,’ said the Prince, and after a brief and rather anguished pause said, ‘until it became irretrievably broken down, us both having tried.’

On that occasion his Private Secretary, Richard Aylard, had reinforced the Prince’s determination to tell the truth, and it was the rest of the world that held their heads in their hands and gasped with incredulity. The Duke of Edinburgh was incensed, the rest of the family flabbergasted, the Queen’s advisers and courtiers stunned, the Prince’s friends appalled, and the blame fell squarely on Richard Aylard for having allowed Charles to make what many regarded as the worst mistake of his life. At the time many people thought it might cost him the throne.

‘It wasn’t being honest to Jonathan that was the problem,’ protested Aylard in his defence. ‘If you want to start placing blame, the fault was getting into the relationship in the first place.’

There is no doubt that Camilla has been an important figure in the Prince’s life since he first fell in love with her at the age of twenty-three. They are the greatest of friends, they have all sorts of interests and enthusiasms in common and they love one another very dearly; it is clearly a warm, comfortable relationship and hugely beneficial to them both, but it hasn’t been an exclusive, obsessive relationship since Charles was twenty-three. He has fallen in and out of love many times since then – probably never more deeply than with Camilla – but he has fallen in love none the less. She was certainly one of the women he was seeing when he started going out with Diana but it was never going anywhere. Camilla was married; even if she had been divorced he could never have married her, not in 1981; a divorcee with two children becoming Princess of Wales? It was unthinkable. Besides, what woman in her right mind would want to?

When Charles first started looking upon Diana as a possible candidate for marriage he talked to Camilla about her; he asked all his close friends what they thought of Diana, and Camilla was one of those who tried to befriend her and welcome her to the group. She invited Charles and Diana to spend weekends at her house. There was nothing sinister in any of this. The fact that Camilla knew Charles was going to propose and hence wrote a friendly note to Diana to await her arrival at Clarence House on the day it was announced wasn’t sinister either. Look at almost any episode of the American TV sitcom Friends: soliciting friends’ approval of the latest girl/boyfriend is par for the course. But the Princess took it as proof that something was still going on between them, and read into Camilla’s friendly invitation to lunch the latter’s desire to find out whether she was going to hunt when she moved to Highgrove, and therefore whether she would be in the way of their plans to meet.

There were no meetings, and virtually no contact until several years into the marriage, and certainly no sex, as the Prince so painfully and honestly explained, until the marriage had irretrievably broken down. And by that time he was close to irretrievably breaking down, too. Towards the end of 1986 he started making contact with friends once again, those he had shut out of his life at Diana’s request some years before. As he wrote to one of them:

Frequently I feel nowadays that I’m in a kind of cage, pacing up and down in it and longing to be free. How awful incompatibility is, and how dreadfully destructive it can be for the players in this extraordinary drama. It has all the ingredients of a Greek tragedy … I fear I’m going to need a bit of help every now and then for which I feel rather ashamed.

He was in such a chronic state of depression by then that they feared for his sanity, and it was Patty Palmer-Tomkinson who engineered a reunion with Camilla, knowing how much she had meant to him in the past. Camilla herself was not particularly happy; she and Andrew Parker Bowles were the best of friends but their marriage was an empty shell with Andrew in London escorting pretty girls all week and Camilla minding the home, dogs, horses and children in the country. At first she and Charles started to talk on the telephone, he pouring out his heart to her, she listening sympathetically, warm, understanding and supportive; then they met at Patty’s house in Hampshire and started seeing each other again, and gradually the relationship developed and they took up where they had left off more than six years before. Camilla was a lifeline for Charles; she brought light and laughter into his life which for a long time had been so very dark.

This was not the outcome Charles had either wanted or anticipated. For years he had longed to be married, to have for himself the family atmosphere that he experienced in his friends’ houses, to have children running around and a companion with whom to share his life. He was lonely; he was surrounded by valets, footmen, butlers, private secretaries and police protection officers. He was never on his own, but ‘he was one of the loneliest men you’ll ever meet. They all are,’ says Michael Colborne. ‘They go out to banquets and dinners and great dos, but when they get home at night they go up to their rooms and they are on their own. There’s no one to have a drink with. They are very independent people; even their friends are mostly acquaintances.’ Charles wanted a soulmate. In a thank-you letter to a friend written on Boxing Day in 1981, when Diana was first pregnant, he wrote, ‘We’ve had such a lovely Christmas – the two of us. It has been extraordinarily happy and cosy being able to share it together … Next year will, I feel sure, be even nicer with a small one to join in as well.’

It had either been a rare moment of calm or wishful thinking. Not long afterwards she was throwing herself down the stairs in a desperate cry for help. The whole situation was a vicious circle. Diana’s chronic need for love and reassurance meant she wanted Charles to be with her 100 per cent of the time – more than that; she wanted his full attention 100 per cent of the time. It was an impossible demand. If she didn’t get it, she raged, and the more she raged the further she pushed him away. Even the most slavishly devoted partner would have found her demands unreasonable; he found them impossible. He was Prince of Wales, he had letters to write, papers to read, speeches to deliver and a diary full of engagements and ceremonial duties stretching ahead for ever. He could have given up all his sporting activities if he had wanted to, but he would never have been able to abandon his work; he simply couldn’t be the husband Diana wanted.