Полная версия

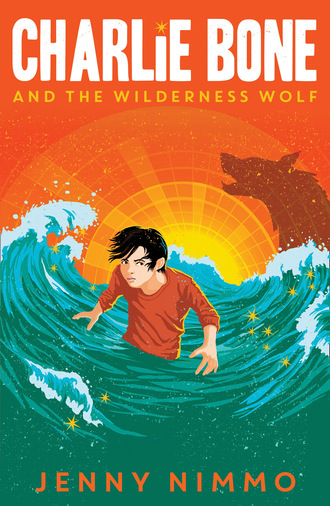

Charlie Bone and the Wilderness Wolf

Paton frowned. He had been meaning to get rid of the rocker. No one else ever used it. It had been a constant reminder of Grandma Bone’s gloomy presence. If only he’d thought ahead and chopped it up for firewood a day earlier.

Creak! Creak! Creak! There she went, with her eyes closed and her head nestled into her chin. Rock! Rock! Rock! The sound was enough to curdle the soup.

‘So,’ Paton found a voice at last. ‘I hear you’ve fallen out with your sisters, Grizelda.’

‘They’re your sisters too,’ she snorted. ‘Marriage indeed! I never heard of such rubbish. Venetia’s fifty-two. She should’ve given up that sort of thing years ago.’

‘What sort of thing?’ asked Charlie.

‘Don’t be insolent,’ his grandmother replied.

Charlie finished his soup and stood up. ‘I bet you’ll leave when my dad comes back,’ he said.

‘Oh, but you’re all going to live in that cosy little Diamond Corner.’ She gave Charlie one of her chilly stares. ‘But then whale-watching can be very dangerous. He may never –’

Charlie didn’t wait to hear what his grandmother might say next. ‘I’m going to see Ben,’ he cried, rushing into the hall and flinging on his jacket.

Maisie called, ‘Charlie, it’s dark, love. Don’t pay any attention to Grandma Bone. She didn’t mean anything by it.’

‘She did,’ muttered Charlie. He left the house, ran across the road to number twelve and rang the bell. Filbert Street was always quiet at this time on a Sunday. There were very few cars about and the pavements were deserted. And yet Charlie felt a prickling at the back of his neck that told him someone was watching him.

‘Come on, come on.’ Charlie pressed the bell a second time.

Benjamin Brown opened the door. He was a few months younger than Charlie and a lot smaller. His scruffy yellow hair was exactly the same colour as the large dog that stood beside him, wagging its tail.

‘Can I come in?’ asked Charlie. ‘Grandma Bone’s back.’

Benjamin understood immediately. ‘What a disaster! I’m just taking Runner Bean for a walk. Want to come?’

Anything was better than spending the evening in the same house as Grandma Bone. Charlie fell into step beside Benjamin as he headed towards the park. With joyful barks, Runner Bean ran circles round the boys then darted down the dark street. Benjamin didn’t like to lose sight of his dog. He knew he worried unnecessarily. His parents were always telling him to lighten up, but Benjamin couldn’t help being the way he was. Besides, a mist was beginning to creep into the street; an unusual, salty sort of mist.

Charlie hunched his shoulders. There it was again. That odd prickling feeling under his collar. He stopped and looked back.

‘What is it, Charlie?’ asked Benjamin.

Charlie told his friend about the not-quite-humans that he’d seen near Diamond Corner.

‘Nothing’s normal tonight,’ Benjamin said shakily. ‘I never tasted salt in the mist before.’

And then they heard the howl; it was very distant, but a howl nevertheless. A sound that was almost human, and yet not quite. For the first time since his parents had left, Charlie wished they hadn’t gone whale-watching.

Runner Bean came racing back to the boys. His coarse hair was standing up like a hedgehog’s.

‘It’s the howling,’ said Benjamin. ‘I’ve heard it before. It makes Runner nervous, though he’s never usually scared of anything.’

It wasn’t until much later that Charlie made the connection between the distant howling and the not-quite-humans that seemed to be following him.

As for the salty mist, that was another thing entirely.

Strangers from the sea

Two strangers had entered the city on that chilly Sunday afternoon. They came on the river. Leaving their boat moored beneath a bridge, they climbed the steep bank up to the road. They moved with an odd, swaying motion as though they were balancing on the deck of a ship. A mist accompanied them: a cloying, salty mist that silenced the birds and gave passers-by unexpectedly chesty coughs.

The smaller of the two strangers was a boy of eleven with aquamarine eyes, like an iceberg underwater. His shoulder-length hair was a dull, greenish brown with a slight crinkle. He was tall for his age and very pale, his lips almost bloodless. He lurched across the cobbles with an expression of grim determination on his thin face.

The boy’s father had the same cold eyes, but his long hair was streaked with white. His name was Lord Grimwald.

When they reached the steps up to Bloor’s Academy, the boy stopped. His eyes took in the massive grey walls and travelled up the two towers on either side of the entrance. ‘It’s a long way from the sea,’ he said in a surprisingly tuneful voice.

‘You must learn to live without the sea for a while.’ The man’s voice had the echo of a damp cavern.

‘Yes.’ The boy put his hand in his pocket. A restful look came into his face at the comforting touch of sea-gold. In his pocket he carried a golden fish, a sea urchin and several golden crabs. They were gifts from his dead mother who had made them from gold found in wrecks beneath the sea. ‘These sea-gold creatures will help you to survive,’ she had whispered to Dagbert. ‘But never let your father know of them.’

As the boy began to mount the steps his father said, ‘Dagbert, remember what I said. Try to restrain yourself.’

Dagbert stopped and looked back at his father. ‘What if I can’t?’

‘You must. We are here to help.’

‘You are to help. I am to learn.’ Dagbert turned and leapt up to the top step. His long legs carried him across the courtyard in a few swaying strides, and then he was pulling a chain that hung beside the tall oak doors. A bell chimed somewhere deep within the building. Dagbert peered at the bronze figures that studded the doors.

‘They are older than the house.’ Lord Grimwald ran his fingers over the figure of a man holding what appeared to be a bolt of lightning. ‘Our ancestor, Dagbert. Remember. We talked about Petrello, the Red King’s fifth child.’

One of the doors creaked open and a man appeared. He was a burly fellow, completely bald and with a square face and small, expressionless eyes. ‘Yes?’ he said.

‘We’re expected,’ Lord Grimwald announced imperiously.

‘Name of Grimwald?’ The man’s eyes narrowed.

‘Were you hoping it might be someone else?’

The man muttered, ‘Tch!’ and opened the door wider. ‘Come in, then.’

Father and son followed the burly figure down a long stone-flagged hall to a door set into one of the oak-panelled walls. ‘The music tower,’ announced their guide, turning a metal ring. The door swung open and he ushered the visitors into a dimly lit passage. At the end of the passage they passed through a circular room and then up a spiralling staircase. On reaching the top of the first flight they turned to their right and entered a thickly carpeted corridor.

‘The doctor’s study is second left,’ said the bald porter. ‘As you said, you’re expected. The Bloors are there. All three of them.’

‘Your name?’ Lord Grimwald demanded. ‘I like to know these details.’

‘Weedon: porter, chauffeur, handyman, gardener. Is that enough for you?’ He stomped back down the stairs.

‘Insolent fellow.’ Lord Grimwald’s greenish complexion turned a nasty shade of terracotta. When he got to the study door he gave it several hard bangs with his fist, instead of the polite knock he might otherwise have used.

‘Yes!’ answered two voices, one deep and haughty, the other an eager screech.

Lord Grimwald and his son went in. They found themselves in a gloomy book-lined room, where a large man stood behind a desk. To one side of the desk an ancient creature sat in a wheelchair. He was wrapped in a tartan blanket and wore a round black hat on his bony head. A few white hairs fell to his shoulders like waxy string. Behind him a log fire lent warmth to the room and a welcome touch of colour.

‘Lord Grimwald.’ Dr Bloor walked round his desk and shook his visitor’s hand. ‘It’s good to meet you. I am Dr Bloor, the headmaster. I trust your journey wasn’t uncomfortable.’

‘We came by sea.’

‘Impossible. We’re miles from the sea,’ said the creature in the wheelchair.

‘We came as far as we could, then took a boat up the river.’ Lord Grimwald shook the clawlike hand that thrust its way out of the tartan blanket.

‘I’m Mr Ezekiel,’ said the ancient man. ‘I’m a hundred and one. What about that, eh? Don’t look it, do I?’ Without waiting for a reply he went on, ‘And this is the boy.’ He made a grab for Dagbert’s hand.

‘His name is Dagbert,’ Lord Grimwald told the old man. ‘He has many other names, but we have decided on the surname Endless.’

‘Because my names are as endless as the ocean.’ Dagbert didn’t flinch when his fingers were crushed in the skeletal hand. In fact, he hardly looked at Ezekiel. His gaze was drawn to a figure in the corner; hunched and dark, its face was averted from the visitors, though it gave the impression that it was listening intently to every word. Dagbert was so taken with this sinister form he forgot to restrain himself.

The flames in the grate flickered and died. A damp mist filled the room and the musty-coloured books that lined the walls were bathed in eerie sea-light.

‘What the dickens?’ uttered Ezekiel, drawing his blanket closer.

‘It’s what he does,’ Lord Grimwald said impassively. ‘Soon Dagbert will achieve his full power, and it will be greater than mine.’

‘Indeed?’ Dr Bloor regarded the boy. ‘An uncomfortable thought for you, Lord Grimwald.’

‘Not at all. Dagbert will not disobey. If he does, he will die. He knows this.’ Lord Grimwald spoke as if his son were not in the room. ‘I didn’t want a child,’ he went on, ‘but then this miracle happened,’ he indicated Dagbert, ‘and I found I couldn’t be parted from it. Our family is cursed, you see. Every time a boy has achieved full power, he has turned against his father and one of them has died. But we have made a pact, Dagbert and I, to work together always. Haven’t we, Dagbert?’

Dagbert gave his father a curt nod.

‘Now, Dagbert, control yourself !’

Dagbert smiled. The sea-light faded and the logs in the grate gave a damp hiss and burst into flame.

‘Interesting.’ Dr Bloor frowned at the boy. ‘As long as he uses his endowment in the right places.’

‘Keep an eye on him for me,’ said Lord Grimwald, ‘and I’ll do what you want.’

‘We’ll put him in Charlie Bone’s dorm,’ Ezekiel said gleefully.

‘Please, take a seat, both of you,’ said Dr Bloor. ‘Dagbert, fetch those chairs by the bookshelf.’

The boy pulled two chairs up to the desk while Dr Bloor continued, ‘Charlie Bone is getting too strong. He needs reining in.’

‘I can do that, sir.’ Dagbert took a seat beside his father.

For the first time since the visitors arrived, the figure in the shadows turned his face to the light. Lord Grimwald gave an involuntary gasp but his son stared at the ruined face of Manfred Bloor with a mixture of awe and fascination. Four great scars ran from the youth’s hairline to his chin. His eyelids were puckered with stitches and his top lip dragged upward in two places, giving the face a permanent grimace.

‘Terrible, isn’t it?’ Ezekiel looked round at his great-grandson. ‘But we’ll get even with them, Manfred.’

‘How did it happen?’ asked Lord Grimwald.

‘Cats,’ said Dr Bloor.

‘Cats?’ Lord Grimwald repeated in disbelief.

‘Leopards,’ came a husky croak from the corner.

‘They lacerated his throat,’ said Dr Bloor in an undertone. ‘Every word he utters causes him pain.’

‘Leopards.’ Dagbert’s eyes hadn’t left the ravaged face.

‘The Red King’s leopards,’ came the dreadful croak.

Dagbert turned to his father. ‘We’re descended from the Red King.’

His father nodded. ‘It’s why we’re here.’

‘So you know the story of the Red King?’ Ezekiel wheeled himself closer to Dagbert. ‘You know that when his wife died, the King went to grieve in the forest with only his leopards for company. But did you know that he turned those leopards into cats? Immortal cats, their coats as bright as flames, cats that turn up every generation to keep company with the children who refuse to be controlled.’ Ezekiel’s voice rose to a furious screech. ‘They did it. Those cats destroyed my grandson.’

‘Why?’ asked Dagbert, undaunted by the old man’s fury.

‘Charlie Bone,’ answered the rasping voice in the shadows.

‘Indeed, Charlie Bone,’ said Dr Bloor. ‘Granted he was trying to save his father, but to do this . . .’ The headmaster flung out his hand towards his son.

‘And have you found a way to punish Charlie Bone?’ asked Lord Grimwald.

‘We’re hoping that you can help us.’ Dr Bloor gave an exasperated sigh. ‘Charlie has friends, you see, friends with powerful endowments. They stick together like glue.’

‘Glue can be dissolved,’ said Dagbert quietly.

A surprised silence followed this remark. The Bloors regarded Dagbert with renewed interest. But the boy’s gaze was held by the scarred eyes that watched him from the shadows, and everyone in the room felt the invisible bond that was instantly formed between Dagbert Endless and Manfred Bloor.

Ezekiel smiled with satisfaction. Many endowed children had studied at Bloor’s Academy; some had been gratifyingly evil, but he was certain that none had been as deadly as this Northern boy with his iceberg eyes.

Lord Grimwald got to his feet and began to move about the room in his peculiar swaying walk. ‘So you will educate my son, and what am I to do for you?’

‘Ah, now we come to the crux of the matter,’ Ezekiel said eagerly. ‘You can control the oceans, Lord Grimwald. A towering talent, if I may say so.’

Lord Grimwald inclined his head as he continued to swing about the room.

Dr Bloor said, ‘Charlie’s father, Lyell Bone, is at this moment upon the ocean. He is taking a second honeymoon with his wife, Amy. And they have decided to go whale-watching.’

‘Whale-watching!’ Ezekiel cackled. ‘Silly fools. They’re going on a little boat, and the waves will rock the little boat from side to side, and then the highest, tallest, widest wave there’s ever been will take the little boat to the bottom of the ocean, where Lyell and Amy will rest forever. What d’you think about that, Lord Grimwald?’

‘I can do that for you.’ Lord Grimwald stopped pacing and sat down. ‘But may I ask, apart from punishing Charlie Bone, is there another reason why you want to drown Lyell Bone?’

‘The WILL!’ said Ezekiel and Dr Bloor in unison.

‘The will?’ asked Lord Grimwald.

‘It’s old, very old, but still legal probably,’ said Ezekiel. ‘It was made by my great-grandfather, Septimus Bloor, in 1865, shortly before he died. He left everything: house, garden, the ruined castle in the grounds, priceless treasures, all . . . all to his daughter Maybelle and her heirs. But my great-auntie, Beatrice, was a witch, you see, and hated Maybelle, so she poisoned her, and forged another will. This will, the false one, left everything to my grandfather, Bertram. And he left it all to my father, and then to me. Beatrice wanted nothing for herself; she was content to see Maybelle dead and her children become paupers.’

‘Forgive me for being slow, Mr Bloor, but where’s the problem?’ Lord Grimwald spread his hands. ‘It would appear that the original will no longer exists.’

‘But it does, it does,’ cried Ezekiel. ‘Someone found it, you see: Rufus Raven, Maybelle’s great-grandson. It was given to his wife, Ellen, on her wedding day.’

‘A will?’ questioned Lord Grimwald.

‘No, no, not the will, exactly. She was given the box that contained it,’ explained Dr Bloor. ‘The key was lost and she couldn’t open it, but Ellen was endowed with an instinct for certain . . . things. She guessed that it contained something of great importance.’

‘We believe that Rufus gave it to Lyell Bone for safekeeping,’ said Ezekiel. ‘They were the best of friends, he and Rufus. We tried to bargain, we tried threats. “Give us the box,” we said, “and you’ll have half our fortune.” Of course we didn’t mean it.’ A sly smile twisted Ezekiel’s meagre lips. ‘But Rufus wouldn’t give it up, anyway. So we had to get rid of him, and his silly wife. A nasty accident arranged by a car mechanic on my payroll. Their baby survived, but he doesn’t know a thing.’

‘His name’s Billy,’ said Dr Bloor. ‘We have him here. He’s eight years old and can communicate with animals.’

‘That’s useful,’ Dagbert said with interest.

Ezekiel giggled. ‘Billy’s endowment hasn’t been very helpful to him so far. Take Percy, for instance.’ He clicked his fingers. ‘Percy, come here.’

An old dog appeared from behind the desk. Its eyes were hidden behind rolls of loose skin and its short legs were barely able to support its heavy body. Dagbert’s lips curled in disgust as the creature grunted and dragged its slobbery mouth against Ezekiel’s blanket.

‘Billy calls him Blessed,’ said Ezekiel. ‘Heaven knows why. The dog can understand Billy’s gibberish but he knows nothing of our conversation. We could be talking about butterflies,’ Ezekiel fluttered his crooked hands in the air above his head, ‘or . . . or birthday parties, for all he knows. So he can’t tell Billy a thing about our little chat, or his inheritance.’

‘Are you sure?’ Dagbert eyed the dog suspiciously.

‘Absolutely,’ said Dr Bloor. ‘The only words that dog knows are his names: Percy or Blessed.’

This wasn’t strictly true. Blessed might not have been able to comprehend every word that was said, but he understood the current of feeling in the room. He knew they were talking about his friend, Billy, and he was aware that the two strangers brought trouble. They smelt of mists and rotting wood. Their skins were cold and slippery, and behind their voices waves could be heard, beating on a stony shore. The boy’s eyes glimmered like frozen water and the man’s face told of wrecked ships and pitiless drownings. Blessed would describe all this to Billy and Billy would tell Cook. And Cook would give Blessed a large bone, Blessed hoped. The old dog made for the door, wagging his bald tail and slobbering badly as he thought of the longed-for bone.

There came a loud knock on the door and, as it opened, Blessed hurried past Weedon into the passage.

‘Cook’s put a bit of supper on the table,’ Weedon announced grumpily.

‘Ah!’ Dr Bloor rubbed his hands together. ‘The dining room is just down the passage. This way, everyone.’

As the two visitors followed Dr Bloor a small woman emerged from the dining room. Cook was rounder than she had once been and her dark hair was touched with grey, but her rosy face still held traces of her former beauty. When she saw Dr Bloor and his guests approaching she stood aside to let them pass.

‘Thank you, Cook,’ said Dr Bloor.

Cook nodded and then gave a small involuntary shudder. She pressed a handkerchief to her face and hastened away. Her heart was pounding so fast that Blessed could hear it as she ran down the stairs behind him.

‘Oh, grief! Oh, horrors! It’s him. It’s him. Oh, Blessed, what am I to do? Why here? Why now?’

Cook burst into the blue canteen with Blessed hard on her heels. The handkerchief was still pressed to her mouth as though the very air she breathed was poisoned.

‘Cook, what’s the matter?’

Cook hadn’t noticed the white-haired boy sitting at a corner table.

‘Oh, Billy, love. I’ve had a dreadful shock.’ She pulled out a chair and sat beside him. ‘A man is here. He . . . he . . .’ She shook her head. ‘Billy, I’ll have to tell you. He drowned my parents, swept away my home and murdered my fiancé, all because I wouldn’t marry him.’

Billy’s wine-coloured eyes widened in alarm. ‘Here? But why?’

‘That I couldn’t tell you. Something to do with the boy he’s brought, I imagine.’ Cook blew her nose and tucked the handkerchief into her sleeve. ‘Grimwald’s his name. It was forty years ago, and I don’t know if he recognised me. But if he did . . .’ She closed her eyes against unimaginable horrors. ‘If he did, I’ll have to leave.’

‘Leave? You can’t leave, Cook!’ Billy leapt to his feet and flung his arms round Cook’s neck. ‘What will I do without you? You can’t leave. Please say you won’t. Please, please.’

Cook twisted her head from side to side. ‘I just don’t know, Billy. There’ve been some pretty awful people in this place, but he’s the worst. And if the boy is anything like him, we’re in for a rough ride, believe me.’

Blessed suddenly put his paws on Cook’s lap and, throwing back his head, let out such a mournful howl that Billy had to cover his ears.

‘He knows,’ Billy whispered. ‘He wants to tell me something, but I’m not sure that I want to hear it.’

Dagbert Endless

On Monday morning a new boy appeared in Bloor’s Academy. He wore the compulsory blue cape of a music student. Charlie met him for the first time in Assembly. The music students had their own orchestra and today Charlie’s friend, Fidelio, was lead violin. He waved his bow at Charlie just as the Head of Music, Dr Saltweather, came on to the stage.

‘Who’s that, then?’ said a voice in Charlie’s ear.

Charlie looked round to see a boy a few inches taller than himself, with long, wet-looking hair and aquamarine eyes.

‘Who’s who?’ asked Charlie.

‘The boy with the violin.’

‘He’s called Fidelio Gunn,’ said Charlie. ‘He’s a friend of mine.’

‘Is he? And is he a good violinist?’

‘Brilliant,’ said Charlie. ‘I’m Charlie, by the way.’

Dr Saltweather raised his hand for silence, and the orchestra struck up.

Thirty minutes later the new boy caught up with Charlie as he left Assembly. He handed Charlie a letter. Charlie didn’t like the look of it. He recognised the Bloors’ headed writing paper. Printed in large, ornate script were these words:

Charlie Bone has been designated official monitor to Dagbert Endless. He will show him all locations relevant to a music student in the second year. He will also acquaint Dagbert with the rules and regulations of this academy, and impart to him any information regarding compulsory attire and equipment. If Dagbert Endless infringes any academy rule, Charlie Bone will be held responsible.

Charlie swallowed hard.

‘That’s me,’ said the boy, pointing to his name on the letter. ‘Dagbert Endless.’

Charlie was baffled. ‘I wonder why they’ve chosen me.’

‘Because you’re endowed,’ Dagbert told him. ‘So am I. Don’t know a thing about music. Wouldn’t mind having a go at the drums, though. What about you?’

‘Me? Oh, I play the trumpet,’ Charlie replied. He wondered why the boy had arrived so late in the school year. They were almost halfway through the second term.

‘I come from the North,’ Dagbert informed him. ‘The far, far North. I was in Loth’s Academy but they expelled me.’

Charlie was instantly intrigued. ‘What for?’

‘There was a drowning,’ the boy said airily. ‘Not my fault, of course, but you know what parents are. They wanted retribution and someone gave them my name.’ Dagbert lowered his voice. ‘He didn’t last long, I can assure you.’

‘Who?’