Полная версия

Cops and Robbers

Lancashire has long been recognised as an innovative force, and the concept of using blue and white cars developed very quickly during the Zephyrs’ trial period in Kirkby – and of the two towns this was considered the very much more successful system.

Because the cars were readily identifiable as police cars, the force could use them to cover a greater area far better and quicker than a bobby on foot patrol. The cars were an instant success and there were calls to expand the idea. At the same time officers were being issued with new hand-held Pye pocket phones, a two-piece personal radio which meant they could now keep in touch with the station. The logic wasn’t that cars became the patrolling medium; the theory of Unit Beat Policing was that the bobby on the beat drove to an area, did a foot patrol, then drove to another area and did another foot patrol or waited to speak to members of the public by his car. Of course, as radio response became ever more immediate, this blurred – but that’s another story. The Government were very much keeping track of these experiments and eventually carried out further trials. The idea was even debated in Parliament under reforming Home Secretary Roy Jenkins at one point; if you are of a mind, you can read this on the Hansard Parliament website. Have a pot of strong coffee to hand.

Lancashire led the way, and in the wake of their success the Government issued a recommendation that forces follow their lead. Ironically, one of the last forces to adopt the system was the Met, who waited until 1970 and then, rather amazingly, introduced Morris Minors as pandas rather than more up-to-date cars, because Morris Minors were a known reliable car that was available and cheap, even if the basic design was from 1948 and the car was getting close to ceasing production – which it did in 1971. As explained elsewhere in the book, the Met had to buy cars that were built in Britain. Some forces, especially those with very different population densities and topography, never adopted the panda car system although they may have used the livery on their cars to a greater or lesser extent. These included the Stirling and Clackmannanshire Police, the Grampian Police and others.

In 1966 Lancashire ordered the first official panda cars. They opted to buy a huge number of Ford Anglia 105Es, 175 in fact, to be used as part of this new ‘Unit Beat Policing’ scheme. On 1 May 1966, local dignitaries and the press were invited to attend Lancashire’s HQ at Hutton for the official launch of the scheme before a mass drive-off of all 175 brand-new blue and white Ford Anglias. The Anglia was chosen because it was cheap to buy, at just £500, and easy to maintain. It didn’t need to be a performance car, as part of the scheme was for the officer to drive to part of his beat, park up in an area where the public could see him, put his helmet on and either walk that part of his beat for a while or wait for the public to approach him by his car. The car didn’t need two-tone horns, just the distinctive blue and white paint to make it stand out.

So where did the term ‘panda car’ come from? None of us has ever seen a blue and white furry bear (well, I hope not for your sake) so it is likely that the name stems from the fact that press interest in this new policing initiative was huge and there were photos of the cars printed in the papers, which of course made them look black and white. The name was either penned by a journalist or more likely was coined by a Lancashire Police mechanic who, whilst reading one of said papers, passed comment that they now looked like pandas! Whichever one it was, the name has now become part of the English language and is a term still used today by police and public alike who are too young to have even been born when the first Anglias rolled out across Lancashire’s sprawling housing estates.

It has also been suggested that the name originated from the term ‘Pursuit and Arrest’, but this isn’t true because the cars were never intended for pursuit purposes. Just to add to the confusion, a couple of years after Lancashire launched the scheme the Home Office conducted an experiment along similar lines with a number of forces being required to paint some of their cars, both unit beat cars and traffic patrol cars, in black with white doors. Forces like Durham, West Riding, Salford City and Plymouth City Police painted cars like the Ford Zephyr, Hillman Hunter, Austin Westminster, Morris 1800S, Mk2 Jaguars and Mini vans in the distinctive colour scheme. They looked great and enhanced the visual impact of the cars, just as Colonel St Johnson had seen in the USA several years earlier. Somewhere along the way things may have blended together and become a bit confused, but whatever the case, the panda car name has stood the test of time even if the original concept hasn’t.

Just about every force in the UK took the system on board, and from 1967 onwards blue and white panda cars were seen everywhere, making the thin blue line a little more pliable. But by 1979 the panda car’s days were numbered, because the police service was being forced to make drastic budget cuts (again, it appears nothing changes …) by the new Conservative government. The fleet manager of the Hampshire Constabulary looked out of his office window at a yard full of blue and white Minis and Mk2 Ford Escorts and concluded that to order the cars in either Bermuda blue for Leyland products or Nordic blue from Ford cost him extra. To then paint the doors white and have to re-paint them blue again prior to selling them off at auction cost £80 per car. He dropped the blue cars, ordered them in white and at the stroke of a pen the idea was lost forever. Fleet managers talk to each other on a regular basis and it wasn’t long before other forces followed suit, although one or two forces like Cheshire and North Wales Police persevered for several years and still had a number of Mk2 Vauxhall Astras and Austin Maestro vans in the familiar colours into the mid-1980s.

Enough of the history, let’s talk cars! So, if Lancashire used the Anglia, did everyone else use the same car? No, thank goodness.

There was a huge variety in the models used, in the make-up of the colour scheme and in the equipment used in or on the cars. But the type of car remained the same; they were basic run-of-the-mill, bottom-of-the-range, small-engine vehicles that were cheap to buy and cheap to run.

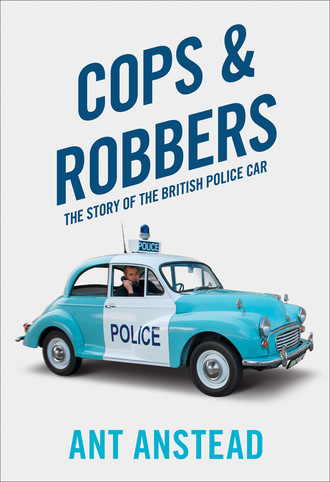

The ubiquitous Morris Minor saloon will be forever remembered as the archetypal panda car – I’ve even used it on the cover of this book – but not every force used them; far from it in fact. The Metropolitan Police, who were one of the last forces to adopt the unit beat scheme, were avid users of the Moggy but also ran fleets of Anglias, Austin 1100s and later the Austin Allegro and the Talbot Sunbeam.

Other forces included Devon, Derbyshire, Bristol City, Sheffield City, Glamorgan, Dyfed-Powys, Cheshire and Edinburgh City, but no doubt the Minor found favour with several others, too. The marque was perfectly suited to this type of work – it was easy to drive, reliable, cheap and (back in the day) looked the part. It wasn’t just saloons that were used either. Believe it or not, the Traveller was used by the Devon Constabulary, Edinburgh City, Leicestershire and Rutland, Wolverhampton Borough and the Ministry of Defence Police. The Minor vans, often referred to as 7cwt vans, had already been used for a number of years as Dog Section vehicles and in plain wrappers as SOCO (Scene of Crime Officer) and Photographic Department units. But now some forces started to paint them in blue and white to utilise as panda cars; however, the Wiltshire Constabulary painted theirs in tan and mustard – apparently they thought that this scheme might blend in rather nicely in the countryside where these cars were used as rural beat units. What were they thinking? The colours made a mockery of the fact that the cars were to stand out from the crowd, not blend in with the hedgerows! Wiltshire stuck with their unusual colour scheme and in later years used it on the Austin A35 van and even the Mk1 Ford Escort. But the Morris Minor has stood the test of time as there are about 20 former police Morris Minor 1000s still in existence with enthusiasts – more than any other type of police car in history. I have even raced against one owned by Chris Rea. He and I had a great battle at Snetterton while I was in the seat of an Austin A35.

Unusually, the Lothian and Peebles Constabulary’s Minors were in the darker Trafalgar Blue and White livery rather than the lighter Bermuda Blue used by most other forces. This was specified by the then Chief Constable, Willie Merilees, who wanted them to stand out from the lighter blue of the otherwise similar Edinburgh City cars.

Morris Minor 1000 ‘panda’ racing car

Guitarist and singer Chris Rea is well known for being a petrol head and, partly because of his Italian ancestral heritage, having a real passion for Ferrari – so much so that he made a film about his F1 hero, Wolfgang ‘Taffy’ von Trips, and commissioned a replica of his famous 1961 Ferrari 156 ‘sharknose’ F1 racing car. However, Rea has also raced in various series over the years, often but not exclusively in a selection of Lotus racers. He also worked occasionally as pit crew, anonymously, for the Jordan team in the early to mid-90s just to be involved (massive respect for that), and has owned a number of interesting road cars. However, as his song lyrics sometimes attest, he’s a man with a dry sense of humour and one of his current racers demonstrates that perfectly: a racing 1959 Morris Minor ‘panda’.

The car on the grid at Goodwood with other Historic Racing Drivers Club (HRDC) racers. The police sign was removed before the race actually commenced.

The car uses a BMC A-series engine as it did originally, but seriously modified and producing near three times its original output, as the 1.75-inch twin SUs and large oil-cooler attest.

Rea bought the car to enter historic racing, having raced as a guest in a couple of HRDC events, and decided he wanted to enter a Minor rather than one of the all-conquering A35s or A40s that dominate the smaller-engine class. HRDC organiser Julius Thurgood found this example rusting away in North Wales, removed it from that particular road to ruin and entrusted it to Alfa Romeo preparation experts Chris Snowdon Racing in November 2014 to be turned into a racing car. The project took the equivalent of one month’s full-time work and, because it was so rusty, ten days of welding alone. Rea apparently briefly considered restoring it as a road car once he realised its police history but decided instead to follow the original plan and nod to the car’s past by finishing it in a panda livery and entering it under the number 999. ‘Pc Rea 6149’ is painted on the doors in reference to Rea’s 2005 song ‘Somewhere Between Highway 61 & 49’.

Now I can hear every reader screaming, it can’t be an ex-panda car if it’s a 1959 as it would have been seven years old, at least, when the livery was introduced! And you’re right, a little liberty has been taken here, but the car is a genuine ex-police car which now provides fun for competitors and spectators alike at events such as the Goodwood Members’ Meeting, so I say good on him. It also shows just how iconic that panda car livery is, at least to a certain generation, plus it was kinda fun seeing Chris’s police car chase me on the track in my rear-view mirror …

The Mini, without question one of Britain’s greatest ever cars, was also very popular with the police in all its variants. Whether it was an Austin 850 saloon, a van, a Clubman estate, a Countryman estate, Leyland or Morris version, or even the Mini Moke, just about every model was used by a force somewhere in the UK. Bedfordshire and Luton Constabulary used large numbers of Minis before the locally produced Vauxhall Viva HB arrived, as did Durham, who chose to paint theirs black and white. Greater Manchester, Norfolk, Merthyr Tydfil, North Wales and Merseyside Police all had Minis, with their minuscule 850cc engine. From 1967 to 1979 the Hampshire Constabulary had no fewer than 900 Minis in service – a record for one make of car that still hasn’t been equalled. The Mini Moke, incidentally, was used by the Devon Constabulary and by the Dyfed-Powys Police, which must have provoked some strange looks from the public as the TV series The Prisoner was on at about the same time and starred the same car in a distinctly more sinister role.

Driving police Mini panda cars could be a very dangerous experience for the unwary copper. Nothing to do with the vehicle’s handling or its performance, but everything to do with the driver’s colleagues. Police officers are amongst the worst wind-up merchants on the planet (together with the military and nurses!) and are constantly thinking up new ways of getting one over on their colleagues. The Mini gave them the ideal tool; it became imperative that at the start of your tour of duty, having got the keys to the Mini panda car, the very first thing you did on opening the doors was to check under the seats. You had to lift the hinged front seats very carefully to check if there was a glass phial stink bomb placed beneath the seat frame. If you failed to check it and merely jumped in the car and sat on it, you were guaranteed a very smelly eight hours!

Two police officers were sent to a domestic dispute at a house and arrived in their Mini panda car. It was such a regular occurrence at this house that only one of them bothered to get out of the car whilst the driver stayed put. But on this particular day it all went horribly wrong. The door to the house flew open and the male occupant came straight out and plunged a large knife into the officer’s face before shutting the door again. The injured officer was bundled into the Mini by his colleague, who didn’t wait for an ambulance and decided to drive straight to hospital. With the knife embedded just below his eye, all the officer could see was the handle bobbing up and down as his panicked colleague drove the Mini panda car with blue light flashing and two-tone horns blaring the four miles across the city to casualty. He drove it as hard as he could with no holds barred, the wrong way down a one-way street, along a pavement, on two wheels around a roundabout with cars and pedestrians leaping out of its way. After emergency surgery the officer later revealed that he was more frightened by the drive in the Mini than he was about the stabbing itself!

The Hillman Imp proved almost as popular with the likes of Kent, Glasgow City, Somerset and Bath Constabulary, Norfolk Joint Police, Newcastle Police and the Dunbartonshire Police. The Somerset cars were somewhat different in that they ordered theirs in the standard Rootes blue, which was a little darker than the light blue that everyone else had adopted. Kent County Police didn’t bother painting the doors white on their early Hillman Imps, although they did eventually succumb to the full colour scheme. However, the prize for the ‘best-looking Imp in the panda class’ goes to the Dunbartonshire Police, who of course were not a million miles from where the Imp was manufactured in Linwood, Renfrewshire. Being canny Scots, they dreamt up a money saving idea to get themselves two pandas without the need for any special orders or additional paint jobs. The solution was to buy two cars – one white, the other one blue – then swap the doors, bonnet and boot lids over. Brilliant. But they did use some paint – bright yellow to be precise, on the roof. The roof colour was complemented by large ‘Wide Load’ signs placed front and rear. The cars were very high profile and gained the nicknames of Pinky and Perky; they were used to escort abnormal loads along the A82 Loch Lomondside Road from Dumbarton to Fort William during heavy construction work at Loch Awe and became tourist attractions in their own right. Although not strictly panda cars (they were actually Traffic cars), the livery alone makes their inclusion here a must. Incidentally, the diecast model manufacturer Corgi made a superb two-model set of Pinky and Perky, which you can occasionally pick up online.

Hillman Imp panda cars

In 1971 Northumberland Constabulary made a drastic error in buying a number of light-blue-coloured Hillman Imp saloon cars to be used in all areas as panda cars. Four burly giant police officers shoehorned into these tiny cars was always going to be a challenge, but the real challenge came whenever the police needed to make a stealthy approach to the scene of a crime. The Hillman Imp’s aluminium, rear-mounted engine (which had its design roots from a Coventry Climax Fire Pump engine) made a distinctive high-pitched whine. Thieves could place lookouts keeping toot, who could hear police cars approaching from afar and make good their escape. The only thing that officers could do to overcome this was to try to approach the scene of crime from an uphill direction, so that they could freewheel to the scene of crime to surprise offenders and catch them red-handed.

Birmingham City Police appear to have been the only force to have used the Austin A40 Farina for its panda car fleet, purchasing dozens of them in 1967 from the local Longbridge car plant. This was a move obviously designed to help with local community relations, as well as to clear some stock at Longbridge of what was by then an out-of-date car coming to the end of its life, thus it was probably available at a heavily discounted price. These cars were fitted with an illuminated roof box and a blue light together with two-tone horns. This was an unusual practice, although not unique. Some forces fitted their panda cars with emergency equipment to assist them in getting to an incident quicker, even though the drivers of such cars had only ever received basic driver training.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s a lot of our city and borough forces had amalgamated into the larger county forces, and at about the same time a variety of new panda cars came on stream, including the replacement for the Morris Minor: another Alec Issigonis masterpiece – the Austin 1100. The Met bought loads of them and they were just as popular with West Midlands, Gloucestershire and the new Devon and Cornwall Constabulary. The 1100 had plenty of interior space and its ride was very smooth thanks to its hydrolastic suspension, but it faced some serious opposition from Ford’s replacement for the Anglia 105E: the all-new Mk1 Ford Escort 1100.

Introduced in 1968, the Mk1 Ford Escort 1100 was an instant success with the public and the police. It was cheap to buy and run, had decent performance and enough space inside. It proved itself to be extremely reliable and cost-effective and officers enjoyed driving them. Forces like Dorset, Merseyside, Hampshire, West Sussex, Lancashire, Suffolk, Wiltshire, Thames Valley, Stirling and Clackmannan Police all used this new Ford product, and most stuck with it when it was later replaced by the Mk2.

The case of the pink Ford Escorts

In 1978–79 Britain was hamstrung by the winter of discontent, so-named because of strikes in the public sector that took the unions head to head with Jim Callaghan’s by then fatally crippled Labour government, which in turn led to Mrs Thatcher’s first election victory. However, the strikes also affected the car industry, and one of the longest-running disputes was at the massive Ford factory in Dagenham. At this time Northumbria Constabulary was wedded to Ford Escorts because it made sense for their maintenance workshops to be set up to deal with only one type of vehicle. They also had been afforded a good deal in terms of the quantity of cars purchased each year. The problem arose when Ford, because of the long-running strike, could not furnish any white-coloured police cars, and in desperation the police, very reluctantly, accepted two pink-coloured panda cars from Ford. One of these cars was placed in Gosforth, a suburb of Newcastle upon Tyne, while the other one ended up at Prudhoe, near Gateshead. The end result was police officers drawing lots to avoid driving the pink panda, and lots of wolf whistles and jokes of dubious taste while they were on patrol if they lost. Perhaps this was a reflection of the attitudes of the period as well …?

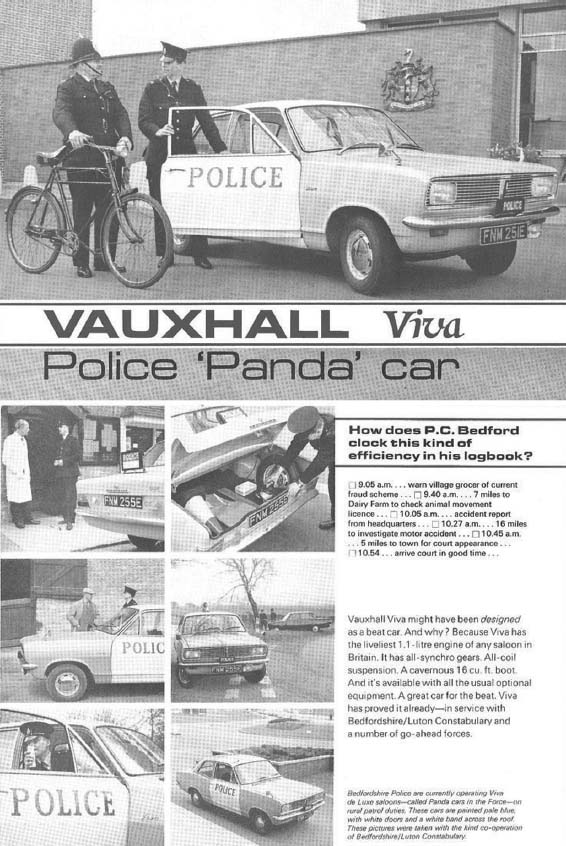

Meanwhile, Vauxhall updated its lacklustre Viva HA model, which hadn’t been looked at by the police, and gave us the Viva HB, which was a direct rival to the Escort. Again, it was cheap to buy and run and appeared to fit the bill (pun intended! You’re welcome …) perfectly. It goes without saying that Bedfordshire Constabulary bought the Viva, as did the neighbouring Hertfordshire, together with Cheshire, Lancashire and the Ayr Burgh Police in Scotland, who did exactly the same as Dunbartonshire Police did with the Imps and bought vehicles in either white or blue then swapped all the opening bits over to obtain that panda car effect. Vauxhall knew they had a winner on their hands and produced a wonderful brochure selling the HB Viva’s panda car potential.

Without doubt the blue and white scheme worked. It grabbed the public’s attention – which was the whole idea, of course – and so a number of forces started to experiment by painting some other vehicles that were never intended to be panda cars in blue and white. Lancashire, for example, took several of its Mk1 Transit Section vans (station vans) and repainted them. The Met Police even utilised a couple of ageing Morris J Series vans in the early 1970s as mobile Careers and Recruitment Offices by painting them up as pandas simply to draw people towards them. Other forces started playing around with the scheme as well. Thames Valley Police had white Mk1 Escorts with dark-green doors, whilst Suffolk Police opted for light-blue doors on white-bodied Escorts. The Renfrew and Bute Constabulary couldn’t quite make up its mind when it took a white Hillman Imp, painted the doors dark blue and then put orange stripes along its sides! Birmingham City Police repainted one of their Austin A60 area cars from black to panda livery with a curious breaking up of the colour on the C-pillars. However, they were used as supervisory units by sergeants in charge of local sub-divisions, who would use these oversized panda cars to check up on the PCs in their standard panda cars and to meet them at certain ‘points’ on their beat. This was an old-fashioned idea left over from the days of foot patrols, when sergeants would meet their officers at a ‘point’ on their beat at a certain time to ensure that they were actually doing their job in their respective area. The sergeant would then sign and date the officer’s pocket notebook. Talk about policing the police!

As the 1970s progressed, other new cars entered the market. We saw the likes of the Vauxhall Chevette (my brother had a brown one) make the odd appearance in forces like Cheshire, Norfolk and Lincolnshire. Ford’s new Fiesta got used by Northumbria, Hertfordshire and West Yorkshire Police. The Vauxhall Viva HC model was also reasonably successful but not quite as much as its predecessor. By the late 1970s one car stood head and shoulders above the opposition; Ford’s new Mk2 Escort in 1.1 Popular trim made for a great panda car. It was light and easy to drive, with sound reliability – even if the driver’s seat tended to collapse under the weight of an overweight policeman! Huge numbers of them were used by the Met, Cambridgeshire, Gloucestershire, Hampshire, Dorset, North Wales, Devon and Cornwall, Essex, Hertfordshire and the Lothian and Borders Police in Scotland, who incidentally still have one in their museum.