Полная версия

Cops and Robbers

Gladiator Voiturette

Ironically, the Clement Gladiator 3.5hp Voiturette could not have been a more unlikely motorised hero, and it was far from the fire-breathing performance machine that its name suggested. It featured a 402cc single-cylinder engine and had a top speed of about 20mph, which it could obviously sustain far longer than a drunk man on a horse …

Bicycle magnate Adolphe Clément first made a fortune producing pneumatic tyres, then later whole bikes, cars, motorcycles, airships and even aeroplanes! He saw the potential of the motor industry early on and invested in or promoted several marques. His Clement Gladiator was basically a Benz copy made by one of these firms, Cycles et Automobiles Gladiator of Le Pre Saint-Gervais, France, which was imported then by Goliath Co. of Long Acre, London. It’s thought they probably made a small number in the UK as well, although sources disagree on that.

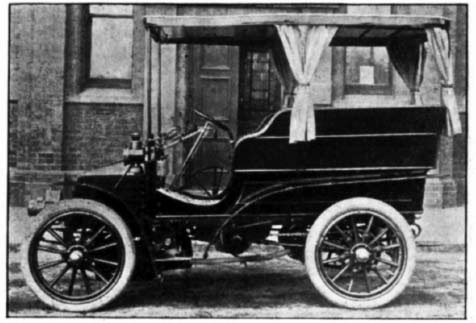

Rather wonderfully, the first cars officially recorded as having been purchased by the police are two 1903 Wolseley 10hp wagonettes (remember this is RAC hp tax, not BHP), touring cars which were purchased for use by the Met’s Commissioner of Police and the Receiver (a strange title to modern ears, which makes you wonder if the police have been placed in receivership, but it is actually the title of the officer responsible for the financing of the force). They were numbered A209 and A210; these number plates were still being used until very recently – A210 was on the Home Secretary’s car in the 1970s, but I’ve not been able to find out where it is now. I’d not realised that the police loyalty to the Wolseley marque stretched back to what were really the first proper police cars in the UK. It gives me a rather warm glow to think of this.

1903 Wolseley, and why the police used this marque for so long

The last Wolseley-badged car, an ADO 71 ‘Wedge Princess’, was produced in 1975, but even today, mainly because of the proliferation of period crime dramas from Miss Marple to Buster, the Wolseley brand is indelibly associated with police cars. There is actually a reason of sorts, but you’d never guess it in a million years because it is to do with, wait for it, submarines …

In 1900 the ailing car side of the Wolseley machine tool business, which had grown from sheep-shearing machines, had been for sale for some months and had not found a buyer. The board had decided that making cars was too complex and, after some exploits that had not been entirely profitable, decided to concentrate on what they knew. That company still exists, successfully, today. The car side of the company was offered with their chief designer, one Herbert Austin, who would of course go on to found a motor company of his own. After almost 12 months of being touted around, and just when the directors were losing faith that it could be sold, the company was purchased by Vickers, even then a much larger concern with interests in defence engineering. The Wolseley car-making operation was moved to an existing Vickers factory, at Adderley Park, in Birmingham, in 1901, and new models were planned.

Vickers was then working on Britain’s top-secret new weapon, the Holland-class submarine, which was the first submarine built for the Royal Navy. This project was meant to be conducted in great secrecy initially, although unfortunately an Edinburgh newspaper leaked the details and left the Admiralty no alternative but to admit to its production. However, although they had been considering diversifying into car production for some time, in hindsight it’s fairly clear that Vickers’ main motivation for the purchase of Wolseley was to set up a discreet operation to work on developing and then building engines for the submarine engineering project; which they did. Doing this in a car factory in Birmingham, many miles away from the boat’s development centre in Barrow-in-Furness or Vickers’ facility in Sheffield, was also of some value when it came to keeping the details secret. Of course, this meant that Wolseley was effectively the car arm of major government defence contractor, Vickers, so what was more natural than ordering government cars from Wolseley? They were actually genuinely very good cars, with a reputation for reliability forged in long-distance trials and a customer list of the great and the good, including royalty both at home and abroad, plus celebrities of the time such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and politicians such as Cecil Rhodes. Wolseley continued to supply a variety of the War Office’s needs (the name of this department was changed to the Ministry of Defence in 1964), including re-engineering the SE5 fighter aircraft’s troublesome Hispano Suiza HS-8 liquid-cooled V-8 engine into the much more reliable higher-compression Wolseley Viper used in the SE5a.

Between 1902 and 1906 Wolseley supplied 27 vehicles to the War Office, including large heavy tractors and six 10hp cars, which were fitted with ‘special tonneau’ bodies for the Royal Engineers. The 10hp wagonette cars ordered by the Met featured a 2-cylinder horizontal engine (not opposed) of 2606cc, lying transversely across the car and allowing the driving of the rear axle by means of chains through a transmission of three gears, although later examples were of a 4-gear design. The engine only revved to 750rpm, which, proclaimed Austin, ensured a longer life than that of its rivals that revved faster. The cost was approximately £370, although that depends on specification since customers could, for instance, choose pneumatic or solid tyres. The first car delivered to the Met was number 284, a 10hp wagonette (meaning the seats in the rear were running along the length of the car rather than facing forward), delivered in May 1903, and the second, number 479, another 10hp wagonette, was delivered in June 1903.

A further car, number 480, yet another 10hp wagonette, was apparently also delivered in June 1903, but there is some doubt over whether this actually was supplied to the Metropolitan Police or to another government agency.

A 1903 Wolseley 10hp wagonette taken from a Wolseley company advert.

Herbert Austin left Wolseley to start his eponymous company in 1904, but the company carried on producing well-engineered cars and became one of the pioneers of mass-production OHC engines, with a design that was in some ways similar to that used in the submarine and aero engines … Unfortunately, Wolseley over-extended themselves in the early 1920s and went spectacularly bankrupt in late 1926. William Morris then bought the company, privately, and integrated it into his car business, which already contained Morris and MG and would, 12 years later, also include Riley. The distinctive illuminated radiator badge, or ‘Ghost Light’ as it was often called, was introduced in late 1932. The formation of BMC in 1952 was effectively a takeover of the Morris (or Nuffield) Group by Austin of Longbridge. Sadly, Herbert Austin had died in 1941 so he never saw his own firm merge with the one where he had built his initial reputation. However, that link and the police’s loyalty to the Wolseley brand, forged in the early days of motoring, continued, especially in the Met, until the Wolseley 6/110s went out of service in the early 1970s.

If you wish to learn more about Wolseley’s fascinating history, I heartily recommend Anders Clausager’s excellent book, Wolseley, A Very British Car, and the importance of his research in uncovering the story above must be noted.

The last Wolseleys used as liveried police cars were 18/85 S Mk2 models used by the City of London Police in 1970, which were based on the BMC ‘Lancrab’. A very small number of the ‘Wedge Princess’ Wolseleys were used as government transport and security cars in London but, as far as we know, not as liveried police cars.

By 1906 the Met Police had six Siddeley vans, which were of a curious technical make-up to modern eyes and reflect the diversity of car design in this experimental era, being fitted with single-cylinder vertically mounted, 6hp 1173cc engines. To show that the car industry has not changed all that much, they were advertised as being ‘Essentially British’ despite the larger models being basically copied from Peugeots! The smaller ones used by the Met were actually re-badged Wolseleys because the Siddeley and Wolseley companies were intertwined at this time, which is no doubt why they were purchased.

At least two were used as despatch vans for carrying correspondence from the Commissioner’s Office at Scotland Yard to the various divisions, and in 1907 they were joined by two larger, 10hp, Adams-Hewitt vans. The Adams-Hewitts were made in Bedford but designed in New York by the Hewitt Motor Co. and, to modern eyes, had quite the most ridiculous advertising slogan: ‘Pedals to Push – That’s All’, because they used a 2-speed epicyclic gearbox. One is tempted to ask whether they steered themselves … By 1912 the Met had added a small number of De Dion-Bouton vans as well.

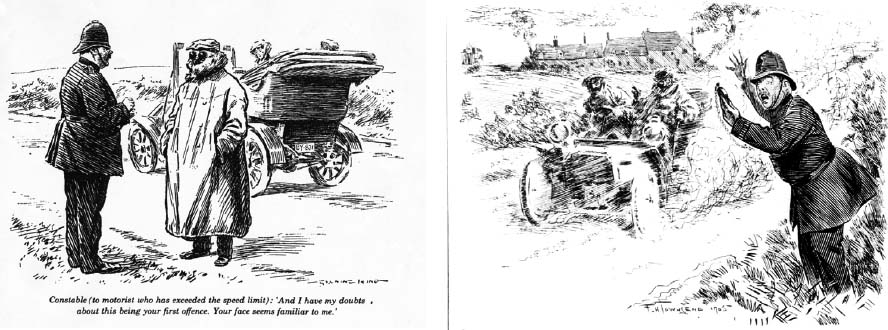

What’s interesting at this point is that although other forces were following the Met’s lead and buying vehicles, they were basically for use to move messages, equipment or, in some cases, men; they were not at this point actually being used for (what I would call proper) police work, which was still done by constables on foot patrols. Instead, they took the role of support vehicles, vans to move things, or cars to transport the higher echelons of the service between different police divisions. Chief Constables tended to be the first to get a proper car rather than a van (and perhaps hindsight could argue that they were the ones who least needed them …), and these were usually reasonably prestigious large cars, nearly always British machines, and often built locally to the regional force that used them. That was not always the case, though; the Chief Constable of Bedfordshire used a Scottish-built Arrol-Johnston, which was, like most of these cars, chauffeur-driven by a constable. Essex Police Chief Constable, Captain Showers, ordered a Belsize 10/12hp car in 1909 and Kent constabulary was quick to adopt this car too, as they had, at this time, the highest percentage of motorists in the UK, probably because Kent was among the richest areas in the country. It should also be remembered that most police officers could not drive, and paying to teach them was an expense that the police tried to avoid, at least initially.

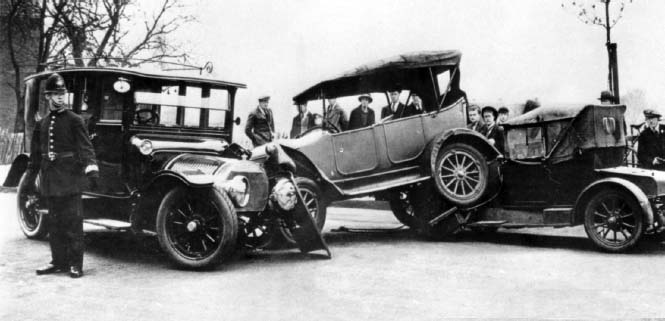

That slow adaptation of mechanised transport and move away from the horse would probably have continued were it not for World War I. In 1914 the army was basically a horse-drawn service with around 120,000 men and fewer than 100 mechanised vehicles in total, including motorcycles. By the end of the war, in 1918, 6.7 million people had joined the British armed forces, and its quantity and variety of vehicles was huge. World War I really was the engine of invention and it’s true to say that it was a major contributor to the advancement of the internal combustion engine; aviation in particular drove advances in engine design and ignition. At the start of the conflict most planes were lucky to make 50mph, but by the end both sides had fighters capable of nearly 150mph. In four years that is astonishing progress, by any measure.

The war also taught a huge number of people, well, mainly men but some women, to drive, so when the government, in debt and battling other issues such as the post-war flu pandemic, decided to sell off the military’s massive vehicle roster there was no shortage of qualified (or otherwise) drivers. Suddenly war-surplus trucks were cheap and most tradesmen could afford to buy one and pension off their horse because the truck was substantially cheaper to run, more reliable and much faster. This was also seen as a move to clean up a society that had been literally awash with horse manure for many years, but in historical terms it was almost an overnight change – from the war ending in a still largely horse-drawn Britain to massive auctions of war surplus vehicles, such as Mac Bulldogs, being sold cheap to anyone who wanted one, in less than a year. This presented three very separate new issues for the police: vehicle theft became a problem, and in addition criminals could use this sudden availability of vehicles to get to and from crime scenes, and the roads suddenly became congested and needed policing – a wholly different problem that put the police into potential conflict with ordinary and normally law-abiding citizens. Policing motorists for speeding or parking wrongly was and remains a totally different problem than catching criminals.

The motor car had come of age, the public were falling in love with their cars, motor-racing heroes such as Sir Henry ‘Tim’ Birkin and Malcolm Campbell were celebrated for their achievements in the new cinema newsreels, and Brooklands was the place to be and to be seen. The post-war world was going to be a wholly different place and Britain’s police service simply had no option but to become a properly mechanised service in order to keep up.

The police ambulances

As the police service became organised and matured through the nineteenth century it may surprise you to learn that a major part of their work was operating an ambulance service and sometimes even a fire service for the local area. This was usually with a hand ambulance – a cart that an officer pulled – while richer boroughs, or areas with a bigger distance to cover, had a horse-drawn ambulance. This continued into the early part of the twentieth century, when both tasks were gradually devolved to separate services in various ways. The government formally devolved the responsibility for ambulances to local authorities in 1930 and, of course, the creation of the NHS in 1948 launched a whole new service. For reasons of space I have focused on ‘policing’ duties and vehicles in this book, as the fantastic work done by ambulance and fire crews deserves a whole separate volume. On a personal note, I worked alongside both services during my time in the police force and I have huge admiration for their professionalism, competency and, it must be said, humour; they do a fantastically difficult job brilliantly well.

CHAPTER FOUR

POST-WAR PEACE; LONDON SETS THE WAY

The Met police reorganised their management of traffic just after World War I started and placed it under one commissioner’s auspices, which, in hindsight, can be seen as the beginnings of the first traffic department. At this time congestion from the mixture of horse-drawn and motor traffic was far worse in London than anywhere else in the UK, even during the war: a conflict which was initially seen as a short-term inconvenience likely to end by Christmas.

However, this scenario lasted five years and the practical experience gained by policing the city’s traffic during the war years had shown the value of having a separate department to deal with these matters in London. The Commissioner, too, saw the wisdom of this and, in writing to the Home Secretary at the end of the war, stated that he proposed to make the temporary wartime arrangement a permanent one. He went on to state that, ‘with the object of securing still further continuity and uniformity, it was desirable that a department should be formed to deal with traffic and to devote its resources to the study of the various and intricate problems that were constantly arising. This would act as an intelligence department by noting all points arising in other Public Departments, or in the press, and also the effect of the statistics prepared by the Executive Department and the Public Carriage Office.’ The Commissioner also said that he ‘envisaged that the new department would also provide a member for the Committee for the examination of Parliamentary Bills and, when required, for the Cab Drivers and the (splendidly named!) Noise Committee (no, this is not a Monty Python sketch). It would also deal with all correspondence on the subject of traffic, including by-laws and licensing. In addition, it would also generally collect and collate all matters appertaining to every phase of the traffic question.’

The Commissioner’s ideas on the need for a new department were accepted by the Home Secretary, and on 24 May 1919 the department officially came into being, having responsibility for all traffic matters, whether vehicular, aerial or pedestrian. The Commissioner, Sir Nevil Macready, in his annual report for the year, said of its formation that:

‘Owing to the increasing complexity of matters concerning traffic, it has been necessary to form a separate department to deal with this matter. The traffic advisers are in close touch with the Ministry of Transport and are thereby enabled to issue and co-ordinate suggestions. There is no doubt that the congestion of the traffic in the Metropolis is, to a great extent, due to existing thoroughfares being out of date and unadapted, either to the volume or the nature of the present traffic conditions. Another factor is the length of time taken to repair streets and roads, no attempt being made to work at night, with the result that traffic becomes hopelessly congested in main thoroughfares for a period which could probably be very considerably curtailed if more up to date ideas prevailed.’

And it appears that almost a century later nothing much has changed!

Traffic policing was born and the new department was to be responsible to the Assistant Commissioner ‘B’, Mr Frank Elliott, and came under the immediate control of Mr Suffield Mylius, a civil staff member, and Superintendent Arthur Bassom, who was in charge of the Public Carriage Office, both men carrying the new title of ‘Traffic Advisor’.

Arthur Ernest Bassom OBE KPM (14 June 1865–17 January 1926), Director of Traffic Services

Bassom was, in many ways, the father of UK motorised traffic control; he thought far ahead of most of his contemporaries and was famed for his incredible memory and encyclopaedic knowledge of all aspects of the motorisation of society. Police Commissioner Sir Nevil Macready admitted publicly at the time that Bassom was the one man in the Metropolitan Police who was indispensable! When he reached the retirement age of 60 (for officers below the rank of Chief Officer), in 1925, he was promoted to Chief Constable and given the title of Director of Traffic Services in order to retain him. He died the following year, still in harness. He was also awarded the Road Transport (Passenger) Gold Medal by the Institute of Transport, just two months before he died. As a mark of respect, it was decided not to fill his position after his death and his duties were absorbed by Assistant Commissioner ‘B’, Frank Elliott.

Bassom joined the Royal Marine Artillery as a gunner at 17 and passed his gunnery examinations with flying colours, which meant he was therefore almost certain of promotion. However, in 1886, just before his twenty-first birthday (the minimum age at which he could be promoted), he joined the Metropolitan Police as a constable. He was posted to ‘D’ Division (Marylebone), and the following year was transferred to the Public Carriage Office at Scotland Yard, where he spent the rest of his career. In 1901 he was appointed Chief Inspector and given charge of the branch just at the time when it was being forced to regulate motor vehicles.

He had a detailed knowledge of motor mechanics and engineering, having qualified in the subject at Regent Street Polytechnic, and kept pace with developments in this area. He produced the Police Regulations for the Construction and Licensing of Hackney (Motor) Carriages, 1906 (The Conditions of Fitness for Motor Hackney Carriages). This included the requirement for a 25-ft turning circle, something that immediately influenced the design of London cabs, and still does, and has had echoes worldwide as well. In 1906 he was promoted to Superintendent on merit. He visited nearly every town in the United Kingdom and many in Europe to observe their traffic problems and learn from their errors, without being too proud to learn from their successes. He framed ‘The Knowledge’, the test undertaken by all London taxi drivers, and devised the Bassom Scheme of London bus route numbers.

He was awarded the King’s Police Medal (KPM) in 1919 and appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1920 civilian war honours list.

I’d like to have met Arthur Bassom. His obituary in the Commercial Motor contained this paragraph, which rather amused me:

‘As a matter of fact, however, he was in nearly every instance able to give better advice than he received. One of his attributes was imperturbability, and he always had the courage of his convictions. He will be sadly missed by the Commissioner of Police, the Assistant Commissioner, Mr Frank Elliott, with whom he came into daily personal contact, and his associates at the Yard.’

You could argue that he was one of the most important men in British history; his theories and actions certainly affected everyone’s life, hugely, and still do today, although very few have heard of him.

Amazingly, as the war commenced, the Met’s records show they still only had two cars – the 1903 10hp Wolseley wagonettes – so at least we can be sure the taxpayer received value from these vehicles, which did at least 11 years’ service! However, the police did have a number of commercial vehicles and forces around the country that subscribed to this principle, with commercials being used to carry messages and equipment and one or two senior officers having cars, although the records of different forces are harder to pin down and some have even been lost. This is why the Met is discussed so much when talking about this early period, and also the Met’s policing of the nation’s capital tended to create policy that other forces followed in this era to a greater or lesser extent. It’s interesting to note that in 1919 the Met actually started to keep a record of its vehicle fleet as a separate entity, acknowledging, at least clerically, that this was going to be a significant part of policing in the 1920s. Following the established principle, the first car purchased in 1919 was a Vauxhall Tourer for the use of senior officers. This model had been a popular military staff car during the war and had an established record of reliable service. It’s worth noting that Vauxhall, in this period, some six years before GM bought them, were known as makers of high-quality, superbly engineered sporting and large luxury cars. GM sent the company in a different, more volume-led, direction.

By the time the traffic department was created in late 1919 they inherited a fleet of 35 vehicles together with workshop facilities for their servicing and repair, which consisted of:

• 1 Vauxhall Cabriolet, for the Commissioner.

• 1 Vauxhall Tourer, for Assistant Commissioner ‘A’.

• 1 Austin 15hp Landaulet, for Assistant Commissioner ‘B’.

• 1 Austin 15hp Landaulet, for the Receiver.

• 1 Siddeley 14hp Tourer, for Superintendent B.3.

• 4 two-seater Humbers, for District Chief Constables.

• 11 two-seater Fords, for Superintendents on outer divisions only.