Полная версия

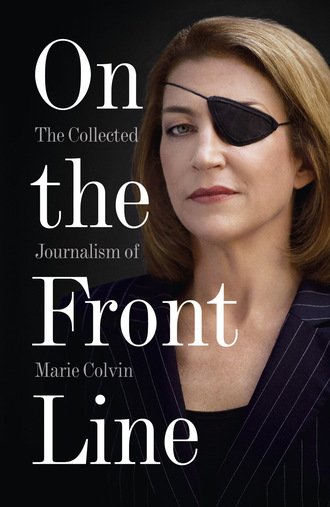

On the Front Line

He is soft-spoken and polite, but old habits die hard. Taking out a cigar, he holds it until somebody lights it, even though the retainers that swarmed around him in his old role as Uday are long gone. He has, however, stopped beating his wife: the violent streak he picked up from his double now sickens him.

Yahia wants to destroy Uday, but he has not changed his appearance because he has no other identity, a dilemma that would have fascinated Sigmund Freud, who lived in the same Vienna street where Yahia’s hideout is.

Yahia’s case is like none Freud ever came across. He grew up in Baghdad, the son of a wealthy Kurdish merchant, and attended the exclusive Baghdad High School for Boys. Uday was in the same class and the two boys resembled each other. ‘But I did not welcome looking similar,’ he said. ‘Uday had very bad manners with people even then.’

After graduating from Baghdad University in 1986 with a law degree, he went off to fight in the Iran–Iraq war, like most young Iraqi males. He was a first lieutenant serving in a forward reconnaissance unit in September 1987 when he received a presidential order to report to Baghdad.

Uday welcomed him in an ornate salon in the presidential palace. There was chit-chat about their schooldays and polite questions about his family before Uday came to the point. ‘Do you want to be a son of Saddam?’ he asked. Wary, Yahia answered: ‘We are all sons of Saddam.’

‘Well, I would like you to be a real son of Saddam, working with me. I don’t want you as protection but as my double.’

Yahia recalled: ‘I was afraid. I knew this was a government of criminals. So I asked him what would happen if I agreed, and what would happen if I refused. Uday told me that if I agreed, “all that you dream will happen”. He said I would have money, servants, houses, women. If I refused, he said, “We will remain friends”.’

Uday left him alone, desperately trying to think up an excuse. When he returned, Yahia had formulated what he thought was a diplomatic way out. ‘All Iraqis want to serve the president,’ he said. ‘I am serving my president as a soldier and I would not like to be more than that.’

Uday’s eyes reddened in rage; he tore the military epaulettes from Yahia’s shoulders and called in security officers. Yahia was blindfolded, driven for an hour in a car (later he would realise he had only been driven around the presidential grounds), and imprisoned in a tiny cell that was painted entirely blood-red.

‘I suffered every kind of torture,’ Yahia recalled. He said he was beaten with a cable, hanged from the ceiling by his hands, fed only bread or rice and water at different times of day so that he would become disorientated. He was told that if he continued to refuse, he would spend the rest of his life in the cell. After a week, he cracked.

Four days later he signed papers promising he would act as Uday’s double and reveal nothing about his activities. The contract ended with a warning: any violation and the penalty was death by hanging. Two weeks later, surgery began at the Ibn Sina hospital in the palace complex. Dentists removed his front teeth and replaced them with teeth like Uday’s; doctors cut a cleft into his chin.

‘I hated myself,’ he said. ‘All my family and friends hated Saddam; so looking like his son, I was disgusted with myself.’

He began his ‘special education’: 16 hours a day watching videos of Uday walk, dance, drive, talk, get in and out of cars, light cigars, drink Scotch. A trainer would then take him through each movement over and over 20, 30, 40 times, day after day until he got it right.

‘I never drank before, or smoked, or danced. I was very correct with people,’ Yahia said. ‘I had to learn to drink Dimple (Uday’s brand of whisky), smoke cigars and talk differently. And I had to learn to be rude with people, like him.’ He also learned intelligence and sabotage techniques, and was taught to check under cars before getting into them.

After six months of intensive training, Yahia made his first public appearance as his double at a football match at the People’s Stadium, where he was surrounded by people who knew the president’s son. With a trainer by his elbow every moment, even driving the black Mercedes 500SL that was Uday’s favourite car, Yahia passed muster. He remembers thinking when he arrived back at the sumptuous villa Uday had given him: ‘Latif Yahia doesn’t exist any more.’

Four lost years followed. Yahia appeared as Uday and travelled with him to London, Geneva and Paris. Whenever Uday wanted a suit – he preferred Christian Dior and Yves St Laurent – he bought two: one for himself, one for Yahia. Uday owned more than 100 luxury cars, and selected them daily to match the colour of his suit.

Outside Baghdad, Yahia would travel in a security convoy as Uday, sometimes with as many as 72 bodyguards. By the time of the Gulf War, Saddam had so much confidence in Yahia that he used him in a cruel confidence trick against his own people. Every Iraqi remembers the visit by Uday to troops on the Kuwaiti front; in fact it was Yahia, sent there with a television crew to counteract truthful reports that Saddam’s family had fled to safety outside Iraq.

During the years of their ‘partnership’, Uday gave him only one rule: ‘Don’t touch my girls.’ At one point, Uday sent him to prison for 21 days because a girlfriend of Uday’s became angry with Yahia, and told the president’s son that he had tried to seduce her. When he was released, his double gave him a Mercedes by way of apology.

Uday often beat his guards, so in public Yahia would have to do the same. He had to learn to curse people; now, in an embarrassed voice, he repeats Uday’s favourites. ‘I would have to say “Your mother is a whore” and things like that,’ Yahia said.

Gradually his public life merged with his private; he is ashamed to admit that he began to beat his wife, Bushra. ‘I would kill Uday if I saw him again,’ Yahia said. ‘I would cut his body into small pieces and feed it to dogs. He made out of me a criminal like himself.’

Yahia was at a party on the river Tigris given for Suzanne Mubarak, the wife of the Egyptian president, when Uday committed one of his worst outrages. Uday hated Kamel Hanna, his father’s favourite retainer, for serving as the go-between for Saddam’s mistress, Samira Shahbandar, wife of the president of Iraq Airways. When Hanna failed to invite Uday to the Mubarak reception, he threw a party nearby out of spite; hearing shots at midnight, he crashed drunkenly into Hanna’s celebration.

Uday saw Hanna firing into the air, Yahia recalled, and ordered him to stop shooting. ‘I only take orders from the president,’ Hanna replied. The night degenerated into violent chaos. Uday cut Hanna’s neck and beat him, then downed pills at the thought of his father’s anger. Both were taken to hospital, where Uday met Saddam waiting for word of his aide.

‘Saddam grabbed Uday by the shirt and said: “If Kamel dies, you die”,’ Yahia said. Hanna died that night, but Uday’s mother intervened to save her son. Yahia worried that he would be executed instead of Uday, but there had been too many witnesses.

Life was not all misery. Yahia had three villas, six luxury cars, all the money he wanted, beautiful women in droves. ‘But I was always afraid,’ he said. ‘I was afraid Uday would kill me. I was afraid of being killed instead of Uday. Nine times I suffered assassination attempts.’

The attempts to kill him were sometimes by family members outraged that Uday had dishonoured their women, sometimes by political opponents. Once, he recalled, an outraged man burst into Uday’s office at the Special Olympic Committee, which he headed, claiming he had raped his young daughter. The father said he had killed his daughter because of the dishonour and wanted satisfaction from Uday.

‘Uday pulled out his pistol and shot him on the spot,’ Yahia recalled. ‘I sat in his office, six metres away. I was not shocked. I had seen it before. I knew I could do nothing.’

Yahia described a permanent atmosphere of fear in the presidential palace. Even those closest to Saddam refrained from speaking openly; everyone was afraid that they would be reported as disloyal, and the penalty was death.

He said Qusay, Saddam’s younger son, who now heads the presidential intelligence agency, was the Iraqi president’s favourite and heir apparent. ‘Uday never called his father “dad”,’ Yahia said. ‘Even in private he addressed him as “your excellency”.’

One of the few people with whom Yahia could relax was Saddam’s double, Fawaz al-Emari. He was the second man trained to impersonate the Iraqi president; his predecessor was killed posing as Saddam in 1984.

Emari had undergone far more extensive surgery than Yahia. His face had been entirely remodelled in Yugoslavia, and Russian doctors in Baghdad had operated on his vocal cords so he would speak exactly like Saddam. ‘Sometimes when I met him, for a moment I would be afraid, thinking he was Saddam. And we were good friends,’ said Yahia.

He and Emari would practise target-shooting together in the palace grounds, which included a swimming pool, cinema, theatre, hospital and sports centre. ‘We spoke about general matters, but never about what we really felt or our activities. We were both too afraid one would betray the other,’ he said.

Both doubles had to undergo weekly medical examinations. Doctors at the presidential palace would check that they were still the same weight as their masters, that their health was good, and that their surgery work remained sufficient for impersonation.

Saddam’s double remains in the palace to this day, a virtual prisoner of his identity. ‘Fawaz had a much more difficult life than me,’ Yahia said. ‘At least Uday went out all the time to restaurants, parties and discos, so I could. Saddam never did these things so Fawaz never could. He could not even go outside and walk on a street looking like Saddam; he would have been killed. He was banned from ever leaving the palace except when he was working.’

Work meant big formal occasions, including a hugely publicised swim by ‘Saddam’ in the Tigris on 26 July 1992. The swim was staged to prove that the president was alive and in good spirits despite the devastation of the Gulf War. In fact, he was afraid to appear in public and exposed his double to danger instead.

Yahia made the decision to flee almost a year after the allies liberated Kuwait in February 1991. His relationship with Uday had become increasingly tense.

‘We were at a party at the Rasheed hotel,’ Yahia recalled. ‘Uday was invited by the president to receive four medals for his role in the Mother of all Battles. I joked, “You are not worth receiving these: I was in Kuwait instead of you.” Uday said there was no difference, but he was not happy with me.’

The danger sign came the next night at another party, when Uday’s ‘love-broker’, who procured girls for the president’s son, upbraided Yahia for refusing to sell him a car. Then Uday also turned on Yahia.

The master apparently sensed that his double was going to make a break for freedom and decided to stop him. As Yahia stepped from a lift into the lobby of the Babylon hotel in Baghdad the next morning, Uday suddenly appeared and shot him. The bullet hit him high in the chest, missing vital organs.

Bleeding heavily, he says, he managed to get to his car and drive north towards the UN-protected safe haven in Kurdistan. To his surprise, Iraqi guards had not been alerted. ‘At every checkpoint, nobody stopped me, they just waved me through. I would see them saluting in my (rear-view) mirror.’

Yahia has the scars to support his story: a round wound in the top of his right chest, an exit hole out the back. As he approached Kurdistan, he needed urgent medical treatment and feared the reception he would get from the Kurds. ‘I could not go directly to Kurdistan. If the Kurds saw me, they would think I was Uday and kill me. So I abandoned my car in the woods, and went to a friend’s house. I am from a Kurdish family, so they helped me.’

Through the Kurdish underground, he reached the American operations headquarters in the Kurdish town of Zakho. The Americans, wary at first, flew in four intelligence officers to debrief him. His wife, who had gone into hiding, was helped out by the same Kurdish underground, and their baby daughter was smuggled to Jordan by friends.

With the help of the Americans, he was granted political asylum in Vienna where many Iraqis live. But an import-export company he set up has failed to prosper and, because of Vienna’s close connections with Baghdad, the city has a high number of Iraqi government representatives. Any one of them, he fears, might be a potential assassin.

His anxiety heightened last September when he received a letter from the Iraqi embassy saying he had been granted an amnesty and should return to Baghdad. The message came on his personal fax machine, even though he is living in hiding and gives the number only to close personal friends.

Yahia is afraid to send his daughter, Tamara, now five, to school in case his whereabouts can be traced through her. He keeps his wife, daughter and Omar, their 18-month son, with him even at the office.

Most of all, he finds it difficult to recover any sense of himself. ‘Uday stole my life, my future, my identity,’ he said. His wife agrees. Watching videos of Yahia posing as Uday in Baghdad, she shivered when she saw the man on the screen roughly grab a tissue proffered by an aide.

‘He changed so much in his manners,’ she said. ‘Before, he was a normal person, but after he was tough and violent. He would hit me or kick me, and many times I thought of getting divorced. But I know now he is trying very hard to recover himself.’

Blood feud at the heart of darkness

8 September 1996

Terrible deaths in the family of Saddam Hussein illlustrate the brutality of a tyrant still powerful enough to shake the world. Marie Colvin reports from Oman.

In the glistening marble and gilt palace of Hashemiya, high on a hilltop overlooking the Jordanian capital, Ali Kamel, nine, spent many hours of his exile drawing brightly coloured pictures for his grandfather. Ali never learnt why he was living in this strange place. He was too young to be told his family had fled there in terror of the grandfather he loved: Saddam Hussein.

Hussein Kamel, Ali’s father, had been the Iraqi tyrant’s closest adviser. He had risen from lowly bodyguard to head of military procurement, and had been put in charge of rebuilding his country after the Gulf War. Kamel even married Saddam’s favourite daughter, Ragda. But he fell out with the dictator’s son, Uday, a thug who had repeatedly killed on impulse.

In August last year, Kamel was in such fear of his life that he took Ragda, Ali and his two daughters across the barren Iraqi desert to seek safety in Jordan. Other members of the family accompanied him in a fleet of black Mercedes.

There was a brother, Saddam Kamel, who had been responsible for the dictator’s personal security. His wife Rana, Saddam’s second daughter, came too, clutching their three children. A second brother followed, with a sister, her husband and their five children.

The family’s terrible fate, details of which are disclosed here for the first time, gives a chilling insight into the methods used by Saddam to retain power despite isolation from the world and hatred at home.

The defection of so many family members was a devastating blow to the tyrant. In the days that followed he retaliated: scores of Kamel’s relatives and followers disappeared. For months afterwards Saddam plotted his revenge with the cunning and lethal aggression that was so much in evidence again last week in his latest challenge to the international order.

Kamel’s family settled comfortably at first into the luxury of the palace provided for them by King Hussein of Jordan. Stuffed with Persian carpets and other finery, it provided them with a secure home behind the shelter of tall, white stone walls.

Ali took lessons from a private tutor. Although the boy did not excel in his academic work, it did not take him long to work out that all was not well with his parents. Kamel had expected to be seen by the world as the potential successor to Saddam. But he had too much blood on his own hands. The Americans came only to pump him for information about the Iraqi military establishment. Even the Iraqi opposition shunned him.

Early in February, Ali often saw his father walking in the palace garden despite the cold and rain, speaking on his cellular telephone. Hussein Kamel had become so disillusioned with exile that he had begun discreet negotiations to return to Baghdad.

It was part of Saddam’s game plan that he responded by making strenuous demands. Not only would Kamel be obliged to return millions of dollars he had hidden in a German bank; he would also have to provide a detailed written account of everything he had told his western interrogators, a lengthy process for a man who was barely literate.

His departure was precipitated by the growing impatience of his hosts with public statements in which he criticised the king. On the first day of the Muslim feast of Eid, he was visited by Prince Talal of Jordan, who told him he was ‘free to go’, the unspoken message being that he had outstayed his welcome.

Kamel strapped a pistol to his hip, drove to the home of the Iraqi ambassador and sat in animated discussion with him in the reception hall. Then they went to the embassy and telephoned Baghdad.

Once he was sure that Kamel had fulfilled the conditions set for his return, Saddam sent a video of himself, in which he promised he had forgiven his son-in-law. ‘Come during the feast,’ he said. ‘The family will be together.’ He implored him to bring all his relatives back with him. A written amnesty followed from the Iraqi leadership council.

Kamel made his decision abruptly. ‘We are going home,’ he announced to a family gathering. Ragda and Rana, suddenly frightened, began crying. At the last moment, Ragda telephoned her mother, seeking reassurance. But the phone was answered by Uday, who, in his latest outrage, had shot an uncle in the leg in an argument over an Italian car that he wanted to add to his collection of classics.

Ragda begged her brother to tell her the truth: would they be safe if they came home? ‘Habibti [Arabic for my love], I give you my word,’ he said.

Hours before he left, Kamel telephoned one of his few friends to say goodbye. The man, a fellow Iraqi, was appalled. ‘You know you are going to your death,’ he said. Kamel bragged that he had obtained personal assurances from Saddam. ‘To this day, I don’t know why he trusted Saddam,’ the friend said last week. ‘He was one of them. He should have known.’

Arriving at the border, the returning defectors were greeted by a smiling Uday in sunglasses and suit. The men were separated from their wives and children. Kamel would never see Ragda and Ali again.

With his brothers, he was taken to one of Saddam’s presidential palaces, where they were rigorously questioned about their experiences in Jordan and their contacts with western representatives and opponents of the Iraqi regime. After three days, they were released and went to the home of Taher Abdel Kadr, a cousin. Here, they were joined by two sisters and the women’s children. But their relief and jubilation were short-lived. Within 48 hours, they learnt from a statement broadcast on television that their wives had denounced them as traitors and had been granted divorces.

As dawn filtered through the windows of their villa on 20 February, a cousin who still worked at the presidential palace woke them with the news that they had been betrayed. He brought weapons. Grimly, the Kamels prepared for their assassins as the children slept on.

Their killing was a family affair. While army vehicles and police cars blocked off the neighbourhood, an armed gang led by Uday and Qusay Hussein, Saddam’s second son, surrounded the house. Uday and Qusay were accompanied inside by the former husband of one of Kamel’s sisters. He showed his loyalty to Saddam by opening the firing on his family’s house.

The attack, carried out with assault weapons, was ferocious. Although Kamel’s men fired back, they were swiftly overwhelmed. Some of the family were killed in the initial onslaught; others when the armed men entered the house. They included Kamel’s elderly father, all the women and at least five young children, gunned down in their nightclothes.

Outside in a parked Mercedes sat Ali Hassan Al-Majeed, a cousin of Saddam’s who had earned the nickname ‘The Hammer of the Kurds’ after gassing villages in northern Iraq with chemical weapons in 1989. Al-Majeed was on a mobile phone, describing each step of the assault to Saddam as it happened.

‘We have 17 bodies,’ he said. The only member of the family who was missing was Kamel himself. Saddam barked: ‘I want his body.’

As bulldozers were brought in to destroy the house, Kamel, naked to the waist, wounded and bleeding, burst from a hiding place inside and appeared at a door brandishing his personal pistol and a machinegun.

He had barely fired a shot before he was riddled with bullets. When the gunfire ceased, Al-Majeed walked up to the body and emptied his pistol into it. He dragged Kamel by one foot through the sand, yelling to his men and to neighbours cowering behind closed doors: ‘Come and see the fate of a traitor.’ The bulldozers moved in and the house was razed.

The massacre was a vivid reminder to the people of the ruthlessness of the regime under which they live. If Saddam was willing to eliminate close and even innocent members of his own family in such a fashion, there was no limit to what he could do to them.

During the summer, however, came two further reminders of the apparent futility of resistance. In June a member of the presidential bodyguard fired shots at Saddam and was executed. Less than a month later, according to western diplomats and Iraqi exiles, a rebel group of Iraqi officers planned to kill Saddam by bombing a presidential palace from a plane that was to have taken off from Rasheed airport in Baghdad.

The conspiracy was discovered and hundreds of members of Saddam’s armed forces were arrested. Between 1 and 3 August, 120 of the officers were executed.

Iraqis have grown used to atrocities since Saddam came to prominence. His first known political act was an attempt in 1959 to gun down Abdel-Karim Qassem, then the Iraqi leader. When he became president 20 years later, he began by accusing 21 senior members of the leadership of treason. He formed a firing squad with his remaining colleagues, and together they shot all the condemned men.

In the years that followed, his people learned to voice their opposition only to close friends and family. Criticism of Saddam is punishable by death, and the security services are ubiquitous. Iraqi couples do not even speak in front of their own children for fear they might innocently repeat something and bring down the wrath of the regime.

The long series of confrontations into which Saddam has led Iraq has made life immensely difficult in a country whose citizens should be as pampered as those of Saudi Arabia. Iraq, unlike most Arab states, has both oil and water. Two huge rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates, nourish the land, and before the imposition of United Nations sanctions following the invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, Iraq earned $10 billion a year by lifting 3m barrels of oil a day.

Much of the money was spent on creating not comfort, but the largest army in the Middle East. Within a year of taking power, Saddam ordered the invasion of Iran, starting a bitter war that lasted for eight years and left 1 million people dead.

The attack on Kuwait was another miscalculation. The 43 days of allied bombing, supported by Arab countries afraid of his might, destroyed not only military sites but roads, bridges, oil refineries, communications, sewage facilities and the rest of an extensive infrastructure built by oil revenues.