Полная версия

Code Name Verity

‘Tessa,’ Maddie said into the telephone, ‘could the German plane be over the Channel?’

Now the whole room held its breath, waiting for Tessa’s disembodied reply as, somewhere underneath the chalk cliffs, she sat staring at the green flashes on her screen. Her answer appeared beneath Maddie’s scribbling pencil: Hostile ident, track 187 Maidsend 25 miles, est height 8,500 ft.

‘Why the hell does he think he’s over the English Channel?’

‘Oh!’ Maddie gave a sudden gasp of understanding and waved at the enormous map of south-east England and north-west France and the Low Countries that covered the wall behind her radio. ‘Look, look – he’s come from Suffolk. He’s been bombing the coastal bases there. He crossed the mouth of the Thames at its widest point and he thinks he crossed the Channel! He’s heading straight for Kent and he thinks it’s France!’

The chief radio officer gave the wireless operator a command.

‘Answer him.’

‘You’ll have to tell me the protocol, sir.’

‘Brodatt, give her the correct protocol.’

Maddie swallowed. There wasn’t really any time to hesitate. She said, ‘What did he say he’s flying? What kind of aircraft? His bomber?’

The wireless operator said the name in German first and they all looked at her blankly. ‘He-111?’ she translated hesitantly.

‘Heinkel He-111 – Any other ID?’

‘A Heinkel He-111. He didn’t say.’

‘Just repeat back to him the type of his aircraft, Heinkel He-111. That’s an open reply. You press this button before you talk, keep it pressed while you’re talking or he won’t be able to hear you. Then let go when you’re done or he won’t be able to reply.’

The chief radio officer clarified, ‘“Heinkel He-111, this is Marck de Calaisis, Calais.” Tell him we are Marck de Calaisis.’

Maddie listened as the wireless operator made her first radio call, in German, as cool and crisp as if she’d been giving radio instructions to Luftwaffe bombers all her life. The Luftwaffe boy’s voice responded in a gasp of gratitude, practically weeping with relief.

The wireless operator turned to Maddie.

‘He wants bearings for landing.’

‘Tell him this –’ Maddie scribbled numbers and distances on her notepad. ‘Say his ID first, then yours. “Heinkel He-111, this is Calais.” Then runway, wind speed, visibility –’ She scribbled notes furiously. The wireless operator stared at the coded abbreviations, then spoke into the headset, giving orders in German with confident calm.

She paused mid-flow and jabbed a perfectly manicured fingernail into the script Maddie had passed to her. She mouthed silently, R27?

‘Runway 27,’ Maddie said under her breath. ‘Say “Cleared straight in, Runway 27.” Tell him to dump his leftover bombs in the sea if he’s got any, so he doesn’t set them off when he lands.’

The whole of the radio room was silent, mesmerised by the sharp, precisely spoken and incomprehensible instructions that the elegant wireless operator rapped out with the careless authority of a headmistress; and the anguished, equally incomprehensible gasped answers of the boy in the ruined plane; and Maddie scribbling directions, and the protocol for giving them, on the diminishing notepad.

‘Here she comes!’ breathed the chief radio officer, and everybody excepting Maddie and the wireless operator – whose heads were tied to the telephone and the radio headset – went running to the long window to watch the Heinkel bomber limping into view.

‘When he calls final approach, just pass him the wind speed,’ Maddie instructed, scribbling furiously. ‘Eight knots west-south-west, gusting to twelve.’

‘Tell him the fire service is on its way to meet him,’ said the radio officer. He clapped one of the other radio operators on the shoulder. ‘Get the engines out there. And an ambulance.’

The black silhouette in the distance grew larger. Then they could hear it, coughing and whining on its single belaboured engine.

‘Christ! He hasn’t got the undercarriage down,’ gasped the young flying officer called Davenport. ‘This is going to be one hell of a prang.’

But it wasn’t. The Heinkel pancaked in neatly on its belly in a shower of grass and turf and came to rest right in front of the control tower, with the fire engines and pumps and an ambulance screaming up to meet it.

Everyone at the window went pelting down the stairs and out to the runway.

Maddie put her headset back on. The two other radio operators were on their feet at the window. Maddie strained to hear what was going on and heard only sirens. Away from the window she could see sky and the windsock at the end of the runway, but not anything immediately below her. A thin thread of curling black smoke drifted up past the window.

Outside at the edge of the runway, Queenie or whatever her name was stood staring at the wreck of the Luftwaffe bomber.

Floundering on its belly, it was like a vast metallic whale spouting smoke instead of seawater. The wireless operator could see, through the shattered Plexiglas of the cockpit, the young pilot desperately trying to free his dead navigator from a torn and bloody helmet. She watched as a swarm of fitters and the fire service team closed in to lift the pilot and the rest of his lifeless crew out of the plane. And she saw the frank relief on the pilot’s face turn to bewilderment and apprehension as he was increasingly surrounded by blue uniforms and the stripes and badges of the Royal Air Force.

The chief radio officer at her shoulder tut-tutted under his breath.

‘Poor young Jerry bastard,’ he intoned. ‘He won’t go home a hero, will he! Must have no sense of direction whatsoever.’

He put a kind hand lightly on the German-speaking wireless operator’s shoulder.

‘If you don’t mind,’ he said apologetically, ‘we could use your help questioning him.’

—

Maddie was going off duty by the time the ambulance men had finished hurriedly patching up the German pilot and brought him into the ground floor office of the control tower. She caught a glimpse of the dazed young man sipping gingerly at a steaming mug while an orderly lit a cigarette for him. They had wrapped him in a blanket, and it was August, but his teeth were still chattering. The pretty blonde wireless operator was perched on the edge of a hard chair at the other side of the room, politely looking away from this shattered and grief-stricken enemy. She was smoking a cigarette of her own as she waited to be given further instruction. She looked just as poised and calm as she had been when she took the headset from Maddie in the radio room, but Maddie could see her casually drilling the back of her chair with one restless, manicured forefinger.

I couldn’t have done what she just did, Maddie thought. We’d not have made this catch without her. Never mind speaking German; I couldn’t have faked it like that, just off the top of my head, no training or anything. Not sure I could manage what she’s going to have to do next either. Thank goodness I don’t speak German.

—

That night Maidsend was raided again. It wasn’t anything to do with the captured Heinkel bomber, it was just an ordinary air raid, the Luftwaffe doing their worst to try to destroy British defences. The RAF officers’ quarters were blown up (no officers in it at the time), and great big holes gouged out of the runways. The WAAF officers were quartered in the gatehouse lodge at the edge of the estate grounds that the airfield had been built on, and Maddie and her bunkmates were so dead asleep they didn’t hear the sirens. They only woke up after the first explosion. They ran through scrub woodland to the nearest shelter in their pyjamas and tin hats, clutching gas masks and ID cards. There was no light to see by except the gunfire and the exploding flames – no street lamps, no cracks of light in any doors or windows, not even the glow of a cigarette end. It was like being in hell, nothing but shadows and jumping flames and fire and stars overhead.

Maddie had grabbed an umbrella. Gas mask, tin hat, ration coupons and an umbrella. Hellfire raining down on her out of the sky and she held it off with a brolly. No one realised she had it of course, until she was struggling to get it in the door of the air-raid shelter.

‘Shut it – shut the damned thing – leave it!’

‘I’m not leaving it!’ Maddie cried, and managed to wrestle the umbrella inside. The girl behind her pushed and one of the girls ahead of her grabbed her by the arm and pulled, and then they were all trembling in the dark underground with the door shut.

A couple of them had had the sense to grab their cigarettes. They passed them around, parsimoniously sharing. There was not a single lad about – the men were quartered half a mile away on the other side of the airfield and used a different shelter – those that weren’t scrambling into aircraft to fight back. The girl with the matches found a candle, and they all settled down for the duration.

‘Bring us that deck of cards, love, let’s have a round of rummy.’

‘Rummy! Don’t be soft. Poker. We’ll play for ciggies. For gosh sakes put that brolly down, Brodatt, are you completely bonkers?’

‘No,’ Maddie said very calmly.

They were all crouched on the dirt floor round the playing cards and glowing tobacco ends. It was cosy in perhaps the way you’d be cosy in hell. Something flying low was peppering the runway with machine-gun fire; even buried mostly underground, even a quarter of a mile away, the shelter’s iron walls shuddered.

‘Glad I’m not on shift right now!’

‘Pity the poor souls who are.’

‘Can I share your umbrella?’

Maddie looked up. Crouched next to her, in the light of the flickering candle and one oil lamp, was the small German-speaking wireless operator. She was a vision of feminine perfection and heroism even in her WAAF regulation issue men’s pyjamas, her fair hair tumbling in a loose plait over one shoulder. Everybody else was shedding hairpins; Queenie’s hairpins marched in ordered rank on her pyjama pocket and would not go back in her hair till she was back in bed. With her slender, perfectly manicured fingers she offered Maddie her cigarette.

‘Wish I’d brought a brolly,’ she drawled in the plummy, educated tones of the Oxbridge colleges. ‘Super idea! A portable illusion of shelter and safety. Have you room for two?’

Maddie took the cigarette, but did not immediately move over. The fey Queenie, Maddie knew, was given to fits of madness such as stealing malt whisky from the RAF officers’ mess, and Maddie was sure that anyone bold enough to impersonate an enemy radio operator on the spur of the moment was entirely capable of mocking someone who burst into tears every time she heard a gun fired. On a military airfield. In a war.

But Queenie didn’t seem to be making fun of Maddie – quite the opposite. Maddie budged over a little and made room for another body beneath the umbrella.

‘Marvellous!’ Queenie cried out happily. ‘Like being a tortoise. They ought to make these out of steel. Let me hold it up –’

She gently prised the handle out of Maddie’s trembling hand and held the ridiculous umbrella up over both their heads inside the bunker. Maddie took a drag on the offered cigarette. After a while of alternately biting her nails and smoking the borrowed cigarette down to a sliver of paper and ash, her hands stopped trembling. Maddie said hoarsely, ‘Thank you.’

‘Not a problem,’ said Queenie. ‘Why don’t you play this round? I’ll cover you.’

‘What were you on Civvie Street then –’ Maddie asked casually. ‘An actress?’

The little wireless operator dissolved in a fit of gleeful laugher, but still steadfastly held up the umbrella over Maddie’s head. ‘No, I just like pretending,’ she said. ‘I do the same thing with our own boys, you know. Flirting’s a game. I’m very boring really. I’d be at university if it weren’t for the war. I’ve not quite finished my first year. I started a year early and a term late.’

‘Reading what?’

‘German. Obviously. They spoke it – well, an odd variant – in the village where I went to school in Switzerland. And I liked it.’

Maddie laughed. ‘You were wizard this afternoon. Really brilliant.’

‘I couldn’t have done it without you telling me what to say. You were brilliant too. You were right there when I needed you, not a word or call out of place. You made all the decisions. All I had to do was pay attention, and that’s what I do all day on the Y sets anyway – just listen and listen. I never have to do anything. And all I had to do this afternoon was read from the script you gave me.’

‘You had to translate!’

‘We did it together,’ said her friend.

—

People are complicated. There is so much more to everybody than you realise. You see someone in school every day, or at work, in the canteen, and you share a cigarette or a coffee with them, and you talk about the weather or last night’s air raid. But you don’t talk so much about what was the nastiest thing you ever said to your mother, or how you pretended to be David Balfour, the hero of Kidnapped, for the whole of the year when you were 13, or what you imagine yourself doing with the pilot who looks like Leslie Howard if you were alone in his bunk after a dance.

No one slept the night of that air raid, or the next day. We had pretty much to resurface the runway ourselves that morning. We weren’t equipped for it, we didn’t have the tools or the materials, and we weren’t a building crew, but without a runway RAF Maidsend was defenceless. And Britain too, in the bigger picture. We repaired the runway.

Everyone mucked in, including the captured German – I think he was rather apprehensive about his fate as a prisoner of war and was just as happy to spend the day stripped to the waist shovelling piles of earth with twenty other pilots than to be moved on to some unknown official internment awaiting him inland. I remember we all had to bow our heads in a moment of silence for his dead companions before we set to work. I don’t know what happened to him after that.

In the canteen, Queenie was asleep with her head on the table. She must have done up her hair first, before she came in from two hours’ stone-picking on the runway, but she’d fallen asleep before she’d even taken the spoon out of her tea. Maddie sat down across from her with two fresh cups of tea and one iced bun. I don’t know where the icing came from. Someone must have been hoarding sugar just in case there was a direct hit on the airfield and everybody needed cheering up. Maddie was quite relieved to see the unflappable wireless operator with her guard down. She pushed the Cup That Cheers close to Queenie’s face so that the warmth woke her.

They propped their heads on their elbows, facing each other.

‘Are you scared of anything?’ Maddie asked.

‘Lots of things!’

‘Name one.’

‘I can name ten.’

‘Go on then.’

Queenie looked at her hands. ‘Breaking my nails,’ she said critically. After two hours clearing the runway of rubble and twisted metal, her manicure was in need of repair.

‘I’m serious,’ said Maddie quietly.

‘All right then. Dark.’

‘I don’t believe you.’

‘It’s true,’ said Queenie. ‘Now your turn.’

‘Cold,’ Maddie answered.

Queenie sipped her tea. ‘Falling asleep while I’m working.’

‘Me too.’ Maddie laughed. ‘And bombs dropping.’

‘Too easy.’

‘All right.’ It was Maddie’s turn to be defensive. She shook tangled dark curls off her collar; her hair was barely short enough to count as regulation and too short to put up. ‘Bombs dropping on my gran and granddad.’

Queenie nodded in agreement. ‘Bombs dropping on my favourite brother. Jamie’s the youngest of ’em, the nearest me in age. He’s a pilot.’

‘Not having a useful skill,’ said Maddie. ‘I don’t want to have to marry right away just so I don’t have to work down Ladderal Mill.’

‘You are joking!’

‘When the war’s over, I still won’t have a skill. Bet there won’t be this desperate need for radio operators when the war ends.’

‘You think that’ll happen soon?’

‘The longer the war goes on,’ Maddie said, carefully cutting her iced bun in half with a tin butter knife, ‘the older I’ll get.’

Queenie let out a giddy, tickled laugh. ‘Getting old!’ she cried. ‘I’m horribly afraid of being old.’

Maddie smiled and handed her half the bun. ‘Me too. Bit like being afraid of dying though. Not much you can do about it.’

‘What am I up to?’

‘You’ve done four. Not counting the nails. Six to go.’

‘All right.’ Queenie deliberately tore her bun into six equal pieces and arranged them round the rim of her saucer. Then, one by one, she dunked each piece into her tea, named a fear and ate it.

‘Number 5, the Newbery College porter. Blimey, he’s a troll. I was a year younger than all the other first years and I’d have been scared of him even if he hadn’t hated me. It was because I was reading German and he was sure my tutor was a spy! Five down, right? Number 6, heights, I’m afraid of heights, that’s because my big brothers tied me to a drain spout on the roof of our castle when I was five and forgot about me all afternoon. All five of them got a good birching for it too. Seven, ghosts – I mean one ghost, not seven, one particular ghost. I don’t need to worry about that here. The ghost is probably why I’m scared of the dark too.’

Queenie washed back these unlikely confessions with more tea. Maddie stared at her in growing amazement. They were still eye to eye across from each other with their chins against their hands and their elbows on the table, and Queenie did not seem to be making it up. She was taking her unlikely inventory very seriously.

‘Number 8, Getting Caught Stealing Grapes From the Glasshouse in the Kitchen Garden. That’s another birching. Course we’re all too old now for birchings and for grape-stealing. Number 9, Killing Someone. By accident or on purpose. Did I save that German laddie’s life yesterday, or destroy it? You do it too – you tell the fighters where to find them. You’re responsible. Do you think about it?’

Maddie didn’t answer. She did think about it.

‘Perhaps it gets easier after the first time. Number 10, Getting Lost.’

Queenie glanced up from dipping Getting Lost in her tea and looked Maddie in the eye. ‘Now, I can see that you are sceptical and disinclined to believe anything I tell you. And perhaps I’m not really worried about ghosts. But I am afraid of getting lost. I hate trying to find my way around this airfield. Every Nissen hut looks the same. My God, there are forty of them! And all the taxiways and aprons seem to change every day. I keep trying to use planes for landmarks and they keep moving them around.’

Maddie laughed. ‘I felt sorry for that lost Jerry pilot yesterday,’ she said. ‘I know I shouldn’t. But I’ve seen so many of our own lads get confused, their first flight over the Pennines. Seems it shouldn’t be possible to confuse England and France. But who knows what you’re thinking when all your mates have been blown to smithereens and you’re flying a broken plane. Perhaps it was his first flight to England. I felt dead sorry for him.’

‘Yes, I did too,’ said Queenie softly, and swallowed the last of her tea as if she were throwing back a dram of whisky.

‘Was it beastly awful, questioning him?’

Queenie gave her an enigmatic little squint. ‘“Careless talk costs lives.” I’ve taken an oath not to tell about it.’

‘Oh!’ Maddie went red. ‘Of course not. Sorry.’

The wireless operator sat up straight. She looked at her ruined nails and shrugged, and patted her hair to make sure it was still in place. Then she stood up and stretched and yawned. ‘Thanks for sharing your bun,’ she said, smiling.

‘Thanks for sharing your fears!’

‘You still owe me a few.’

The air-raid siren went.

Ormaie 11.XI.43 JB-S

Not Part of the Story

I must record last night’s debriefing because it was so funny.

Engel flapped down my sheaf of scribbled-on hotel stationery in frustration and said to von Linden, ‘She must be commanded to write of the meeting between Brodatt and herself. This description of early Radar operations is irrelevant nonsense.’

Von Linden made a sound like a very soft puff of air, like blowing out a candle. Engel and I both stared at him as though he’d suddenly sprouted horns. (It was a laugh. He didn’t crack a smile, I think his face is made of plaster of Paris, but he definitely laughed.)

‘Fräulein Engel, you are not a student of literature,’ he said. ‘The English Flight Officer has studied the craft of the novel. She is making use of suspense and foreshadowing.’

Golly, Engel stared at him. I of course took the opportunity to interpose wi’ pig-headed Wallace pride, ‘I am not English, you ignorant Jerry bastard, I am a SCOT.’

Engel dutifully slapped me into silence and said, ‘She is not writing a novel. She is making a report.’

‘But she is employing the literary conceits and techniques of a novel. And the meeting you speak of has already occurred – you have been reading it for the past quarter of an hour.’

Engel shuffled pages in frenzy, hunting backwards.

‘Do you not recognise her in these pages?’ von Linden prompted. ‘Ah, perhaps not, she flatters herself with competence and bravery which you have never witnessed. She is the young woman called Queenie, the wireless operator who takes down the Luftwaffe aircraft. Our captive English agent –’

‘Scottish!’

Slap.

‘Our prisoner has not yet elaborated on her own role as a wireless operator at the aerodrome at Maidsend.’

Oh, he’s good. I would never in a million years have guessed that SS-Hauptsturmführer Amadeus von Linden is a ‘student of literature’. Not in a million years.

He wanted to know, then, why I was choosing to write about myself in the third person. Do you know, I had not even noticed I was doing it until he asked.

The simple answer is because I am telling the story from Maddie’s point of view, and it would be awkward to introduce another viewpoint character at this point. It is much easier writing about me in the third person than it would be if I tried to tell the story from my own point of view. I can avoid all my old thoughts and feelings. It’s a superficial way to write about myself. I don’t have to take myself seriously – or, well, only as seriously as Maddie takes me.

But as von Linden pointed out, I have not even used my own name, which is what confused Engel.

I suppose the real answer is that I am not Queenie any more. I just want to thump my old self in the face when I think about her, so earnest and self-righteous and flamboyantly heroic. I am sure other people did too.

I am someone else now.

They did used to call me Queenie though. Everybody had stupid nicknames made up for them (like being at school, remember?). I was Scottie, sometimes, but more often Queenie. That was because Mary, Queen of Scots, is another of my illustrious ancestors. She died messily as well. They all died messily.

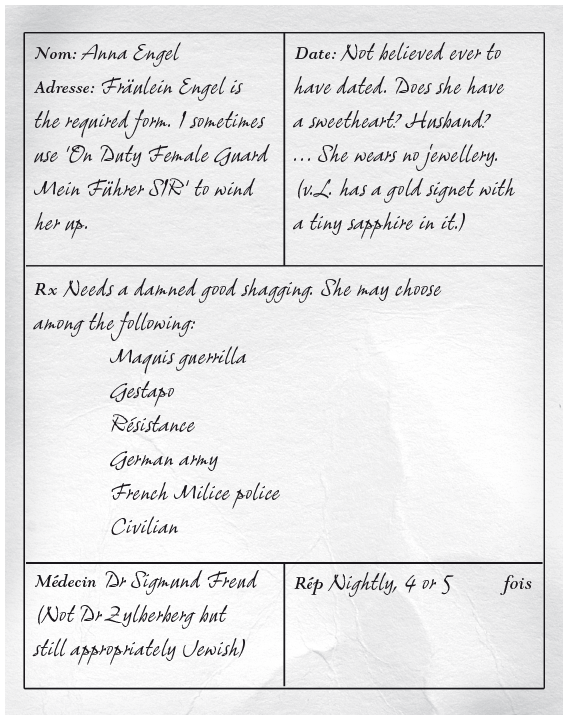

I am going to run out of stationery today. They have given me a Jewish prescription pad to use until they find something more sensible. I did not know such things existed. The forms have got the doctor’s name, Benjamin Zylberberg, at the top, and a yellow star with a warning stamped at the bottom, stating that this Jewish doctor can only legally prescribe medication to other Jews. Presumably he is no longer practising (presumably he has been shipped off to break rocks in a concentration camp somewhere), which is why his blank prescriptions have fallen into the hands of the Gestapo.

Prescription Forms!

I’ve done her a nicer one, as well.