Полная версия

The Captain's Mysterious Lady

James was on his way to Bow Street to pay Henry Fielding a visit. He had not caught his wife’s murderers thanks to that coach overturning and the delay in arriving at Peterborough, where the trail had gone cold. He had returned to London, along with thousands of others who had decided the threat of more earthquakes had been exaggerated and the world was not about to come to a violent end. Rather than go to his Newmarket estate, he decided to stay with his parents at Colbridge House, expecting Smith and Randle to return to the metropolis as soon as they thought the coast was clear but, in two months, none of his contacts had seen or heard anything of them. London’s Chief Magistrate had been a great help to him over his quest in the past and he might have heard something of them.

The street was crowded with people going about their business, jostling each other in their hurry to reach their destinations: city men, gentlefolk, parsons, hawkers, women selling posies, piemen, street urchins. James hardly spared them a glance as he made his way on foot to the magistrate’s office, where he found him in conversation with Lord Trentham, a one-time admiral, whom he had known from his years of naval service.

‘Now, here’s your man,’ the magistrate said to his lordship, after greetings had been exchanged and a glass of brandy offered and accepted. ‘He can help solve your mystery.’

‘Oh, and what might that be?’ James asked guardedly, assuming they wanted to inveigle him into more thieftaking.

‘A man has gone missing and his lordship wants him found.’

‘Men are always going missing,’ he said. ‘I know of two myself I should dearly like to find.’

‘Still no luck?’ Henry queried.

‘Afraid not. I have been chasing them all over the country. What we need is a paid police force, one that investigates crime as well as arresting criminals, a body of men in uniform that everyone can recognise as upholders of law and order.’

‘I agree with you,’ the magistrate put in. ‘I am working on the idea and one day it will come about, but in the meantime I must put my faith in people like you.’

‘That has come about because of my determination to see Smith and Randle hang.’

‘Bring them before me, and they will,’ the magistrate told him. ‘In the meantime, will you oblige Lord Trentham?’

‘I assume the missing man is a criminal of one sort or another?’ James enquired.

‘We do not know that,’ his lordship put in. ‘Might be, might not. His wife’s family want him found.’

James laughed. ‘An absconding husband!’

‘We do not know that either.’

‘It is a mystery,’ Henry Fielding said. ‘And you are a master at solving riddles and can be trusted to be discreet.’

‘That is most kind of you,’ he said, bowing in response to the compliment. ‘But I am not at all sure I want to solve this particular riddle. Coming between husband and wife is not something I care to do.’

‘Let me tell you the story and then you can decide.’ Lord Trentham said.

‘Go on.’ He was availing himself of the magistrate’s best cognac and politeness decreed he should at least hear his lordship out.

‘The wife in question is the daughter of a very dear friend, Lady Sophie Charron—’

‘The opera singer?’

‘The same. Two months ago she was on a coach travelling to her relatives in Highbeck, in Norfolk, when the coach was held up by highpads, only for it to be overturned half an hour later. She has recovered from her injuries, but cannot remember anything leading up to the accident. Her memory is completely blank. And her husband has disappeared. The house where they lived is a shambles. We are of the opinion something happened.’

James had begun to listen more intently as the tale went on, realising they were talking about his mystery lady. He had often wondered what had become of her, had not been able to get her out of his mind, even after he had been to Peterborough and back. Her pale, frightened face haunted him. How could he be sure he had left her in good hands? Was this another occasion for guilt that he had done nothing to help her? Was his pursuit of Smith and Randle robbing him of his common humanity? He had toyed with the idea of calling to see how she fared, but Highbeck was remote and not connected with his own search and he could not be sure she was still there so he had put off doing so.

‘I met the lady,’ he said quietly. ‘I was travelling on the same coach.’

‘You were?’ Lord Trentham leaned forwards, his voice eager. ‘Then you know more than we do.’

‘Not about her husband I do not. I did not know she was married.’ He went on to tell them exactly what had happened and his impressions of the demeanour of the young lady. ‘She was at the inn being looked after by the innkeeper’s wife when I left. I was assured her relatives had been sent for and would take care of her, but I have often wondered if I was right to leave her.’

‘Oh, yes, her aunts, Lady Charron’s sisters, fetched her and she is staying with them at Blackfen Manor,’ his lordship explained. ‘But her husband has disappeared. They think if he could be found, her memory might be restored to her.’

‘What do you know of him?’ James asked.

‘His name is Duncan Macdonald.’

‘A Scotsman?’

‘I believe so, though he has lived many years in England. He is an artist, though not a very successful one. He also plays very deep and I believe the couple were in financial trouble. It might be why he has disappeared.’

‘A cowardly thing to do, to leave his wife to set off alone for her relatives, don’t you think?’ James remarked.

‘Yes, if that is what he did, but perhaps he had disappeared before she left. She might have been going to look for him,’ his lordship suggested.

‘She chose a singularly unattractive helpmate if that was the case. A surly individual in a rough coat and a scratch wig. She seemed terrified of him. Also, he was known to the robbers who held up our coach. And I believe she recognised them as well, although I may be mistaken in that,’ James said.

‘Oh dear, it is worse than I thought,’ said Lord Trentham. ‘Did you by chance learn the man’s name?’

‘Gus Billings, I think one of the highpads called him, but he died in the accident. Could he have been her husband under an assumed name?’

‘Unlikely. I only met Duncan Macdonald once when we attended the same opera and he and Amy came back stage to speak to Lady Charron, but he wore a bag wig and was dressed in a very fine coat of burgundy satin. He was charming enough, had exquisite manners, but there was something about him that made me wary. Amy was, is, a dear girl, certainly not a lady to consort with criminals.’

‘As you say, a mystery,’ James said, turning over in his mind what he had learned, which was little enough. At least he now knew the young lady’s name was Amy. He thought it suited her.

‘You will undertake to investigate, my dear fellow, won’t you?’ his lordship pleaded. ‘Her mother and her aunts are all anxious about her and I promised I would do what I could to help.’

‘Memory is a strange thing,’ he said. ‘Sometimes it shuts down simply to avoid a situation too painful to bear. One must be careful not to force it back. Mrs Macdonald might be happier not remembering.’

‘True, true,’ Lord Trentham said. ‘But if we could discover what is at the back of it without distressing her, then we might know how to proceed.’

James was torn between taking on the commission and continuing the search for his wife’s killers, but that had lasted so long and yielded so little reward he did not think it would make any difference if he set it aside for a week or two. He would do what he could to help, if only to make amends for not doing anything before. ‘If you would be so good as to furnish me with a letter of introduction to the lady’s aunts, I will go to Highbeck and see what I can discover,’ he said. It ought not to take him long and after that he must resume his search for Smith and Randle. He would not rest until they were caught.

Lord Trentham wrote the letter; once this was done and handed to him, James returned to Colbridge House to instruct Sam to pack for a stay in the country, realising, as he did so, that once again he had unwittingly found himself embroiled in uncovering crime.

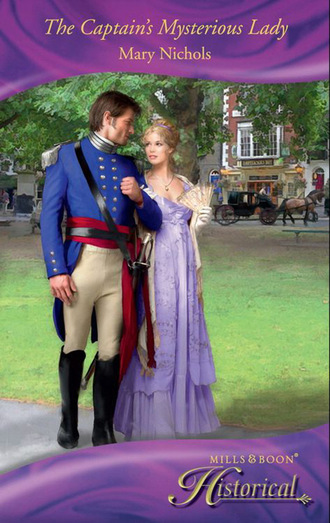

Amy was just leaving the mill next to the King’s Arms, where she had gone to buy flour to make bread, when two horsemen rode into the yard of the inn and dismounted. The taller of the two hesitated when he saw her and looked for a moment as if he were going to speak. He was broad as well as tall, handsome in a rugged kind of way, with intense green eyes that seemed to take everything in at a glance, including her scattered thoughts. His tricorne hat covered sun-bleached hair, which was tied back with a narrow black ribbon. As with any gentleman who came to the village from outside it, she wondered if he might be Duncan, but when he sketched her a little bow and proceeded into the inn without speaking, she knew it was not the husband she looked for, for surely he would have spoken to her, taken her into his arms, called her by name?

The man had looked slightly familiar, as if she ought to know him, or at least was acquainted with him. Did that little bow confirm it? Or was it simply a courtesy? If only she could remember! She went on her way to make her purchase, intending afterwards to visit Widow Twitch, an old lady who lived in a cottage down a lane on the other side of the village who, according to her Aunt Matilda, had known her since she was in leading strings and was also recognised as a wise woman who had the gift of telling the future. Her advice might be worth listening to.

James had recognised Amy immediately and had been on the point of greeting her, but decided against it. He had wondered if she might remember him, considering he had held her in his arms on the ride from the scene of the accident to the inn. The memory of that had certainly stayed with him. He had spoken to her later and she had remembered his name then, but today, though she had looked at him, there had been no recognition in her blue eyes. Until he had spoken to the Misses Hardwick and ascertained exactly what they wanted of him, he would remain incognito.

He was glad to see that she looked well. Her cheeks were rosy and her hair, which had been so unkempt and tangled, was now brushed and curled into ringlets, over which was tied a simple cottager hat. She wore a striped cotton gown, a plain stomacher and a gauze scarf tucked into the front of it, an ensemble that would be decried in town, but was perfectly suitable for the country. She had filled out a little too, so that she bore little resemblance to the waif he had held in his arms. It was difficult to believe that her mind retained nothing of her past. Would reawakening her memory, even supposing it could be done, fling her back into that world of fear? She had been afraid, of that he was certain.

He did not need to eat, having dined at the Lamb in Ely not two hours before, so he left his baggage at the inn where he had booked rooms for himself and Sam, and hired a horse to take him to Blackfen Manor, leaving his own mount to be groomed and rested. He wondered if he might overtake the young lady, but there was no sign of her as he trotted along a well-worn path bordering fields of as yet unripe barley.

He passed the tower at the gates to the grounds and proceeded up a gravel drive until the Manor came into view. He did not know what he had expected, but the solid red-brick Tudor mansion with its mullioned windows and twisted chimneys was a surprise. He half-expected the drawbridge to be raised to repel raiders, but laughed at his fancies when he saw the bridge down and the great oak doors wide open. He trotted under the arch into a cobbled yard and dismounted at a door on the far side.

He was admitted by an elderly retainer who disappeared to acquaint the ladies of his arrival and take in the letter of introduction James had been given. He returned in less than two minutes and conducted James to a large drawing room where two ladies rose as he entered. He removed his tricorne hat, tucked it under his left arm and swept them a bow. ‘Ladies, your obedient.’

‘Captain, you are very welcome,’ the elder said. She was in her forties, he supposed, tall and angular. The other was shorter and rounder, but both were dressed alike in wide brocade open gowns with embroidered stomachers and silk underslips. They wore white wigs, topped with white linen caps tied beneath their chins. ‘I am Miss Hardwick and this is my sister Miss Matilda Hardwick. We are Lady Charron’s sisters. Please be seated.’

‘Glad we are to see you,’ Miss Matilda said, as they seated themselves side by side on a sofa. ‘You will take tea?’

‘Thank you.’ He sat on a chair facing them as tea was ordered. While they waited for it, he used the opportunity to look about him. The plasterwork was very fine and so were the wall tapestries, though they were very faded and must have been hanging there for generations. Some of the furniture was age-blackened oak, but there were also more modern sofas and chairs. There were some good pictures on the walls, a fine clock on the mantel, together with a few good-quality ornaments. A harpsichord stood in a corner by the window. Of Mrs Macdonald, there was no sign.

‘Have you any news?’ Matilda asked eagerly. ‘Has Mr Macdonald been found?’

‘He had not been located when I left the capital,’ James said. ‘The word is out to look for him, but I have come to make your acquaintance and endeavour to discover how much Mrs Macdonald remembers.’

‘Absolutely nothing at all,’ Matilda answered. ‘We have tried everything.’

A servant brought in a tray containing a tea kettle, a teapot and some dishes with saucers, which he put on a table. Harriet took a key from the chatelaine at her waist and unlocked the tea caddy. James watched her for a minute in silence, as she carefully measured the tea leaves into the pot and added the boiling water. They were, he concluded, careful housekeepers, though whether from choice or necessity it was hard to tell.

‘Tell us about yourself,’ commanded Harriet, handing him a dish of tea.

He smiled. He was evidently not going to be taken on face value. ‘My name, as you will have learned from Lord Trentham’s letter, is Captain James Drymore. I am the second son of the Earl of Colbridge. I am twenty-seven years of age and have spent most of my adult life as an officer on board several vessels of his Majesty’s navy. Two years ago I sold out and returned to civilian life.’

‘Are you married?’ Matilda asked.

‘I am a widower.’

‘I am sorry for it,’ Matilda said. ‘But no doubt a handsome man like yourself will soon marry again.’

‘Tilly!’ her sister admonished. ‘You must not put the Captain to the blush like that.’

Matilda coloured and apologised.

‘Think nothing of it, Miss Matilda,’ he said with a polite smile—marrying again was the last thing on his mind. ‘It is natural for you to wish to know all about me if I am to be of service to you.’

‘Oh, I do hope you can be. Amy will be back directly and you will be able to judge her for yourself.’

‘Unless I am greatly mistaken, I have already met the young lady,’ he said. ‘I was on the coach with her when it overturned.’

‘You were?’ Matilda put down her tea in order to sit forward and pay more attention. ‘Then you must know all about it. What happened? Did you speak to Amy? Did she speak to you? Who was the man who died? My sister saw his body when they laid it out at the inn before burial and she is sure it was not Duncan Macdonald.’

‘Ah, that was the first question I meant to ask you,’ he said.

‘We have no idea who he could have been,’ Harriet said. ‘Or what he was doing with Amy.’

He told them about the journey, the highwaymen and the accident, but left out the fact that their niece was afraid of her escort and that he was known to the highpads. He saw no reason to distress them unnecessarily. ‘Will you tell me about Mrs Macdonald and her husband?’ he asked when this recital was finished. ‘It is necessary to know as much as possible, you understand.’

‘Yes, of course,’ Matilda put in. ‘We raised Amy. She is like a daughter to us. She met her husband, Duncan Macdonald, during a visit to her mother in London just over five years ago. We were shocked when she said she was going to marry him. We knew so little about him, except that he was a close friend of her father. She does not even remember that.’

‘He is an artist,’ Harriet said. ‘Or so he says, though we have seen nothing of his work.’

‘But you did meet him?’

‘Yes, the first time soon after they married and again about two years ago when they came to stay for a while. I am afraid I did not take to him. He was a little too charming to be sincere and he had Amy like that.’ She turned her thumb to the floor as she spoke. ‘But perhaps I do him a disservice. You must draw your own conclusions.’

‘How can he?’ Matilda said. ‘The man has disappeared.’

He smiled at the lady’s undeniable logic, and then turned as the door opened and Amy herself came into the room. She stopped uncertainly when she saw him scrambling to his feet. He bowed. ‘Mrs Macdonald.’

‘This is Captain Drymore,’ Harriet told her. ‘Do you remember him?’

Amy looked hard at the man who stood facing her. It was the one she had seen that afternoon at the King’s Arms, but underlying that was the feeling she had experienced then, that she had met him before. How could you forget someone as big and handsome as he was, a man with a commanding presence and clear green eyes that looked into hers in a way that made her catch her breath? ‘I saw him arriving at the King’s Arms this afternoon…’

‘Before that,’ Matilda said.

‘No.’ She turned to James. ‘Should I remember you?’

He smiled. ‘I would have been flattered if you had. We were both aboard the coach that overturned.’

Her sunny smile lit her face. ‘Then you must be my mysterious saviour.’

‘I did no more than any gentleman would have done.’

She sat down beside him, so close her skirts brushed his knee, and turned to face him. ‘Tell me what happened. Every little detail.’

Acutely aware of her proximity and the scent of lilacs that surrounded her, he repeated what he had told her aunts, no more, no less.

‘And did I tell you anything of why I was making the journey?’

‘No, madam.’

‘There was a man with me. I am told he died. Do you know who he was?’

‘I am afraid not. Perhaps he was a servant, someone your husband trusted to see you safely to your destination?’

‘Perhaps. But, you see, my husband has disappeared…’ She stopped. ‘Now, why should I bother you with my concerns when you have been so kind as to come and enquire after me?’

He bowed in acknowledgement, deciding not to set her straight on the reason for his visit. He felt he could learn more by not appearing an interrogator. ‘I have often wondered what became of you and, as I have business in the area, I decided to pay my respects. Are you fully recovered from your injuries?’

‘Indeed, yes, they were only a few scratches and bruises. The worst of it is my lack of recall, but my aunts assure me that is only temporary.’

‘I am sure it is,’ he murmured.

‘And is it not strange that the Captain is known to Lord Trentham?’ Miss Matilda put in.

‘Ah, then perhaps had we met before through his lordship?’ she said, turning to James.

‘I do not think so,’ James said. ‘I am sure, if we had, I should have remembered it. Someone as charming as you would not be easily forgotten.’ He had been so long out of polite society that he surprised himself with the ease with which the compliment rolled off his tongue.

‘Thank you, kind sir.’ She gave a tinkling laugh, which seemed to indicate she was not overburdened with memories of her fear and again he wondered if it were wise to interfere.

‘Where are you staying, Captain?’ Miss Hardwick asked him.

‘At the King’s Arms, madam. It is convenient for my business.’

‘If your business is not too pressing, would you care to have supper with us? We have so few visitors, especially from the capital, I am sure we have much to talk about.’

‘Thank you. I shall look forward to it.’ He rose to take his leave, as she rang for Johnson, the footman, to see him out.

‘Will seven o’clock be convenient?’

‘Perfectly.’ He bowed to each in turn, according to seniority and took Amy’s hand to convey it to his lips.

She felt a shiver of memory pass through at his touch, but it was gone in an instant. That was always happening to her, a faint flicker of recollection that was gone before she could grasp it. She repossessed herself of her hand and bent her knee in a curtsy. ‘Until this evening, Captain Drymore.’

After he had gone, she sat down with her aunts. ‘When the Captain said he was on that coach I hoped he would be able to enlighten me a little,’ she said wistfully. ‘But he does not seem to know anything.’

‘Perhaps we will learn a little more over supper,’ Harriet said. ‘He might jog your memory with some small thing that happened. I hope he is going to stay hereabouts for a little while. It is so agreeable to have visitors.’

‘And such a pleasant man,’ Matilda said. ‘He almost makes me wish I were young again.’

‘Tush, Tilly,’ her sister chided her. ‘You are too old for daydreams.’

‘I know.’ It was said with a sigh. ‘But he is a handsome young man, do you not think so, Amy?’

‘Yes, I suppose he is,’ she said slowly, unwilling to admit she had found him extraordinarily attractive. And somewhere in the back of her mind a tiny memory was stirring, a memory that made her blush to the roots of her hair. Not only had she met him before, she had been held in his arms!

‘You are a married woman, Amy,’ Harriet said, making her wonder if her aunt could read her mind. ‘Just because you cannot remember your husband, does not mean he does not exist.’

‘Is Duncan handsome?’ Amy asked.

‘Some think so.’

‘Did I?’

‘Oh, I am sure you did.’

‘I wish I knew where he was. I wish…’ Oh, she had too many wishes to enumerate them all, but above all, she wished she could remember who she was. Widow Twitch had talked in riddles about trials to come and a search for treasure that would end in a death, but not her death. She was to put her trust in those sent to help her. Who they might be, the old lady could not tell her.

‘Patience, my dear, patience,’ Matilda said, as Harriet hurried off to confer with the cook about the supper menu. ‘It will all come right in the end, I am sure of it. Now, what will you wear tonight? You must look your best.’

The question gave her another problem. The clothes the aunts had found for her were a mix of some she had left behind when she married because they were worn or outdated, some of her aunts’ that had been altered to fit and some bought on a shopping expedition to Downham, the nearest town. Not wishing to be a financial burden on her aunts, she had been careful not to be extravagant. She could not understand why she had embarked on the journey to Highbeck without money or baggage. Aunt Harriet had said it must have been stolen from the wrecked coach before it had been retrieved, or perhaps the highwaymen had taken it.

That was another thing. The coach had been held up only minutes before it overturned, which must have been a frightening experience, but she did not even remember that. She would ask the Captain more about that at supper. Thinking of supper reminded her of her aunt’s question.

‘I think the Watteau gown we altered will do well enough,’ she said. The soft blue taffeta sack dress had been one of Harriet’s and was not intended to fit closely. Its very full back fell in folds from shoulder to floor and the front was laced over white embroidered stays and finished with a blue ribbon bow just above her bosom. The same ribbon decorated the sleeves, which fitted closely to the elbow and then frilled out to her wrists in a froth of lace. It had been easy to alter it to fit her.