Полная версия

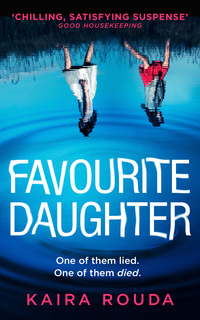

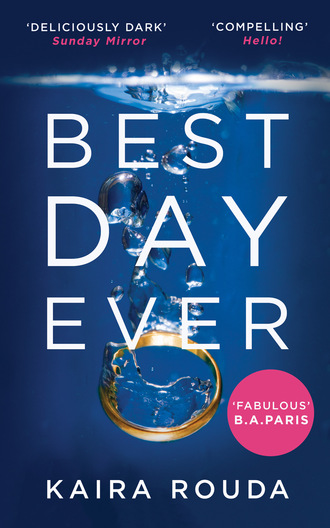

Best Day Ever

“Or beans. Green beans. Those would be fun to grow,” I say in a concerted effort to play along. I have a passion for green beans and have since I was a child. I’ve learned not to question why. It’s just a fact, like the impossibly blue May sky or the brown-green fields stretched out for miles on either side of the car.

I remember when I was a kid and my parents took us to a fancy restaurant in town—this was long before their tragic accident, of course. Before everything changed. Just goes to show you, one thing can happen and poof, all bets are off.

People said it was an odd twist of fate, bad luck that both of my parents had decided to take a nap in the afternoon. Mom’s friends in the neighborhood told the police my mom hardly ever rested during the day. But she had Alzheimer’s, early stage, so things changed all the time. Bottom line was she did take a nap that day. My dad was slowing down in his old age even though he was stubborn and wouldn’t admit it. He napped daily. While my mom’s disease was progressing, she still functioned, still had more energy than he had. Sure, she forgot little things like her neighbor’s name, but until then she hadn’t forgotten big ones—like turning off the car when she had parked it in the garage, most notably.

But my dad always napped, from twelve thirty to two every afternoon. He’d pull out his hearing aids, put the golf channel on the television and commence his obnoxiously loud snoring. He sounded like an uncontrolled train screeching down the tracks. I can almost picture my mom returning from her errand, pulling the car into the garage and pushing the button to close the garage door. She’d walk inside the house, accidentally leaving the door connecting the garage to the house open, the car running. She would have heard my dad’s freight-train snores coming from the bedroom and for some reason, that afternoon, she’d decided to join him in bed. Maybe she had too much to eat at lunch that day and had a stomachache, maybe that’s why she decided to take a nap? The investigators found a bottle of Tums on her bedside table.

It comforts me to know they both slipped into death, like when you have anesthesia for a surgery. The nurse slides the IV in your arm and before you can count backward from ten, you’re out. But in their case, they never woke up. The silent killer, that’s what they call carbon monoxide. I made sure to install detectors in our house after it happened, even though only about four hundred people a year die from the colorless, odorless toxic gas. Still, you have to be cautious, consider every threat. Be one step ahead of everything, everyone. That’s how the universe is working these days.

But before the tragedy, back when I was a kid, my parents would sometimes take us to the fanciest restaurant in town. It would only be when my dad was in a good mood, when he got a bonus and hadn’t blown it yet on booze or whatever. We’d dress up in our little suits and ties, and Mom would beam and tell us we were the most handsome men ever and then we’d drive to The Old Clock Tower restaurant. All the staff would dote over my brother and me. That’s where I had my first taste of perfectly prepared green beans, sliced thin and painted with a buttery mustard sauce. I remember the beans glistening in the light from the candle on the table. I can still taste that first bite, the smile it put on my face. Those beans weren’t anything like the ones we had at home.

Mia and I don’t have a family restaurant we take the boys to on a regular basis. Not one with flickering candles and crisp white tablecloths at least. We manage to sit down together fairly regularly at the kitchen table. Never at the dining room table, not yet. The boys are too messy to be dining above our fine Tabriz rug. A gift from Mia’s parents, a souvenir from one of their exotic vacations, of course. I checked online one day. The rug is worth almost $70,000. So we stick to the kitchen for family meals, though neither Mia nor I would be considered a good cook, not by any stretch.

Sometimes I’ll help throw something together, but usually Mia is in charge of meals, truth be told. Obviously this makes sense: she is the housewife. I’m uncertain why, then, after all of our years together, she hasn’t grown and developed her cooking expertise. I know she’s invested in cookbooks, and cooking classes even, but still, her best efforts can only be awarded a C. Barely edible, actually, when compared to fine dining. The boys and I struggle through “Momma Mia’s Lasagna” every week on Italian Tuesdays. Every week, it’s soggy and almost tasteless. It’s a shame, really.

On the rare occasions when I’m in charge of mealtime, I like taking the boys to Panera. It’s not quite like going to McDonald’s or Wendy’s for dinner—although I’ve been known to do that, of course. Please don’t tell Mia, though. No, Panera is almost a sit-down establishment, a step above, say, a pizza joint or fast food. Sometimes I try to talk the boys into eating green beans there, you know, for tradition’s sake. They don’t have the taste for them, though. Mikey actually grabs his throat and makes choking, gagging sounds at me. He doesn’t eat anything that’s the color green, Mia says. She says he’ll come around, his taste buds will mature. In my day, those taste buds wouldn’t really have a choice, thanks to dear old dad. You ate what was served to you. But I love my kids. Those little guys. Despite the family resemblance, sometimes I like to wonder aloud if they’re mine, they’re so perfect.

“Green beans,” Mia echoes, pulling me from thoughts of parents and offspring and crumbs on expensive rugs. Her back is to me; she seems fixated, fully focused on the farmland rolling by the window. Even though I cannot see her face, I detect a tone in her voice, something that sounds like the feeling you get when you can’t understand a joke. Like you are the joke, like you are an idiot. Only someone you love can make you feel that way. “I can ask Buck if that’s possible, over the summer.” I notice she’s nodding, the landscape is rolling and the overall effect is dizzying. I turn my eyes back to the road.

Since when do we consult with good old Buck on all things garden-related? I wonder. And what else do Buck and Mia discuss: The weather, the pros and cons of fertilizer, our marriage? Soon the road will narrow, and it will be down to one lane, each direction. That’s when I’ll really need to pay attention. That’s when it gets dangerous. If you make a mistake, there is no forgiveness on a two-lane country road.

10:30 a.m.

2

This monotonous stretch of highway, the section between Columbus and, say, the big Pilot Travel Center where we typically stop for gas, is boring: flat, semigreen farmlands, and few sights out the window to feed your imagination. Usually when we hit this point in the journey, I start daydreaming about the destination, thinking about that first moment when I’ll see the lake again.

I know what you may be thinking: Is this guy really daydreaming about Lake Erie? Yes, I am. If you’ve never been you’re probably envisioning the dead lake of the late 1960s fed by the burning Cuyahoga River. By that point, Lake Erie had become a toxic dump thanks to the heavy industries lining its shore, the sewage flowing into it from Cleveland and the fertilizer and pesticide runoffs from agriculture. Dead fish littered its banks. This poor lake was the impetus for the Clean Water Act in 1972, thank goodness.

Or, more recently, you may have heard of the toxic algae blooms that turn the lake water into green goo that looks like the slime they spray on people during that teen awards show the boys like to watch. But that doesn’t happen all the time. Sure, there are invasive mussels and some nasty, dead-fish smells in the air sometimes. But mostly I find, if I sit on a bench near the lake and just listen to the water playing with the boulders along the shore, I feel at peace. It’s hard to explain, I suppose, to someone who has never seen a Lake Erie sunset. But they’re beautiful. And, if you don’t turn your head too far left or right, you can almost imagine you’re at the ocean. It’s almost possible to believe that you could start your life over again, just as the sun drops into the water. And then everything would be simple, just like the little lakefront community where our lake house is nestled under a big oak tree. Sounds romantic, doesn’t it?

Our lake house is part of a special, gated community appropriately named Lakeside, a Chautauqua community started by Methodist preachers more than 140 years ago as a summer retreat for adult education and cultural enrichment, with a heavy dose of religion sprinkled in. Not that there’s anything wrong with religion, of course; it’s just that I didn’t grow up with it, and we’re not raising our kids in it. That doesn’t mean we don’t enjoy the amenities these fine Christian souls have blessed the community with. Even an atheist like me can appreciate its many glories.

At one point or another, Presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Rutherford B. Hayes stayed at Lakeside. My wife likes to note that Eleanor Roosevelt stayed here, too. Mia quotes that woman a lot. I don’t. I find her to be too ugly—I mean, that face of hers is hideous. I could never wake up every morning to a face like that. But Mia doesn’t care about that. Says Eleanor Roosevelt inspires her to do one thing every day that scares her. I’m paraphrasing but you get the idea. I tell her seeing that woman coming at me in a dark alley would have scared me and Mia doesn’t laugh.

The point is, it’s a great little community, and it’s located on a peninsula, halfway between Toledo and Cleveland. But don’t think of those big, dirty cities that the weather maps have forgotten. Imagine instead a place right out of Mayberry RFD. Remember that TV show? No, I’m not old enough to have watched it, of course, but just think about Ron Howard and freckles and simpler times—that’s this place. Its wooden cottages were originally designed to use the lake as the only air conditioner. Now with global warming, most of them have central air.

There’s a little main street with a pizza parlor, a shop selling the best glazed, potato donuts in the world, T-shirt stores and the rest. We have a historic inn built in 1875 that sort of seems haunted to me, what with its old, uneven wood floors, squeaky screen doors and musty smell others might call charming but that gives me the creeps. The windows are too tall, too narrow in my opinion, like inside there is something to hide. The place was supposed to be bulldozed in the mid-1970s, half of its rooms as unusable as the lake was polluted. It was saved from demolition by a group of Lakeside residents and they’ve been sprucing it up, slowly, ever since. Good for them, although I doubt they ever actually stay there. But it is right on the lake and it’s what they call gracious.

My favorite spot in the whole community is the dock and the boathouse. It’s so all-American with its decorative Victorian scalloped roofline, its prime position in the heart of the place. I can just imagine the important visitors arriving by boat back in the day. I like the way I feel when I stand at the end of the dock. The backdrop complements me like a movie set: oh, look, there’s handsome, wealthy city-dweller Paul Strom enjoying a carefree day of leisure at his lakefront community. Very presidential.

Not sure any current-day presidents even make it to Cleveland, our distant neighbor to the east, let alone to our little haven by the lake. But that’s just fine with me. Enough people have discovered it already. When the boys were tiny, we’d come up once a summer and stay with the Boones, our neighbors two doors down back in Columbus. That lasted about three summers or so, and then we started to rent our own place. When we saw the Boones at the pizza parlor after, it wasn’t even that awkward. They’d moved on, invited other neighbors to take our place at their huge cottage. We weren’t able to buy a place of our own until last summer and when we did, it was a cottage on the very same street as Greg and Doris Boone’s stately second home. Not as big, of course. Ironically, though, because we’re up the street we’re on a higher lot so we look down over their property now. It was a dream come true, especially for Mia.

We like visiting Lakeside best just before and after season. Season is the ten weeks in the heart of the summer when the place is crazy packed with tourists and the gates are down. Even homeowners have to pay the stupid gate fees during the summer. That doesn’t make any sense to me, but it’s the way it is.

But, on the plus side—and today is a day for positivity, I remind myself—Lakeside is wonderful, especially during the relatively deserted off-season times like now. I remember our first trip up here, back when we were newly married, the Boones having invited my wife and me up to stay for the weekend. We were thrilled for a chance to leave baby Mikey at home with my parents and have a weekend on our own, just the two of us and some other young parents. It was the start of the good times at Lakeside, and it was all thanks to the Boones. We’d play card games, especially euchre. Drink too much, eat too much, and then the guys would smoke cigars on Greg Boone’s back porch while the women relaxed in oversize white wicker chairs with pink cushions on Doris Boone’s front porch and gossiped. We could hear them, laughing and making fun of things, probably us, from the back porch. Us guys all rolling our eyes; women will be women, you know.

If you ask me, I’d tell you I’m still not really sure what happened, why the Boones stopped inviting us up, but it doesn’t matter. We managed to take ourselves up here every summer, no invitation necessary, and rented great places all on our own. And now we actually own a cottage, perched on a grassy lot above the Boones’ place. If I sit on my screened-in porch at night, I’ve noticed I can even watch Greg on his back porch, with his male guests du jour, smoking all his smuggled-in Cuban cigars. But who needs lung cancer? Not me. No, I think it all worked out beautifully.

Like the Boones’, our primary residence is located in the highly coveted Grandville suburb of Columbus, the city’s nearest northwest suburb, and is approximately two hours south of Lake Erie. All of what we own in the world is in Ohio, in this politically decisive, coastally deprived state. I am a native, born in the suburb we are raising our family in. Don’t tell anyone, but it wasn’t considered upscale back then. No, Grandville has grown into its—well, grandness, to use an apt term—as the Ohio State University and Columbus grew in prominence and wealth. Before, Grandville was a community filled with butchers and factory workers and the like. Now it’s filled with country-club brats and men like me who don’t ever have calluses on their palms. It’s like my dad and me, actually. Callous versus refined. But as far as picking a place to call home, not only did the apple not fall far from the tree in my family, but our crab apple tree was actually started by a seed from the apple tree in the next yard over. Literally my parents had lived right next to us. Before the accident.

Yes, I bought the home next to my parents, even before I met Mia. I knew where I wanted to live, and when it became available, I was there. Life requires planning, don’t you agree? My wife had grown comfortable with the arrangement, though of course, like any new bride, initially Mia had her concerns. She wasn’t from here, so she didn’t understand how close family can help you out, how nice it would be for the kids to know their grandparents and be able to toddle over to their home. She came to appreciate the setup, after our home was whipped into shape. Naturally, I let Mia and her mom completely renovate the place. You wouldn’t even recognize it from my primitive man cave days. But that was all part of the plan. I provided the shell, a “fabulous 1931 masterpiece,” according to the Realtor’s brochures, “that just needs some TLC.” Mia and her parents provided the TLC and much more. Our wedding gift. As a thank-you, I presented Phyllis, Mia’s mom, with a vintage Italian Mosaic pillbox.

“This is fabulous, thank you. I’ll add it to the collection, next to the other one you gave me. You are just so thoughtful. And I don’t have any mosaics, how did you know that, Paul?” Phyllis’s bony arms had wrapped around my waist. I tried not to flinch.

“Just a lucky guess, Phyllis,” I managed, although of course I knew. I’d saved a photo Mia took of Phyllis’s collection, the little trophies displayed on a mirrored table in Phyllis’s dressing room. It’s very important to keep your mother-in-law on your side.

On mornings like this, before my parents died, we would have walked the boys across the green grass of our lawn and then over to the front walk of my mom and dad’s one-story house, depositing them for safekeeping for the weekend. My boys weren’t old enough yet to notice how small their grandparents’ home was, compared to the rest of the street. I’m just waiting for the new owners to smash it down, build a McMansion.

But anyway, back when the boys were little the smell of my mom’s famous chocolate chip cookies would have greeted us at the door and the comforting sound of cheers from fans at some sporting event would be blasting from the television set my dad turned up too loud. The rocking chair my mom had used to calm me as a child had been returned to the corner of my parents’ bedroom. The tub of wooden blocks I’d played with as a kid magically appeared in my parents’ family room as soon as Mikey was old enough to start creating forts.

Sounds idyllic, doesn’t it? Just as life should be for my privileged sons. Doting grandparents next door, a luxurious home to live in filled with pricey furnishings, a stay-at-home mom and a hardworking dad. My boys had it made. And they loved my parents, especially my mom. As for me, as long as my dad and mom both followed my rules everything was perfect. Family is family. Family first, and all that. If you aren’t needed, then fine, make other plans. But grandkids come first. They only violated that rule once, my parents. In my book, you always make time for your favorite son’s kids, no matter what. I’m sure you agree.

Of course, now that my parents are gone we rely on babysitters of varying skill levels. In retrospect, my parents, despite their age, probably would have done a better job of keeping my sons safe than the gangly teenagers we now employ and overpay.

My parents would have been a better choice for this weekend, for example, undoubtedly more effective than Claudia, who arrived this morning looking overwhelmed. Big dark circles hung below her wide eyes and her nails were bitten to the core. Maybe she’s on drugs, I think suddenly, wondering if I should ask Mia her opinion. Better not, though. She’d want to turn around and rescue the boys. We need this time together, this great day together. Claudia isn’t the only one who is overwhelmed; she just looks the most like it.

I’m pretty adept at covering my emotions. For instance, my wife always wonders if it bothers me, living next to the ghosts of my parents. She doesn’t put it that way, just says things like it’s odd seeing the new family painting the front door a different shade of brown. I think it’s odd they haven’t torn the thing down, but I don’t say that. Things like that, the little things, don’t get to me. Big things, those bother me, but still I might not show it. “Poker-face Paul,” my friends called me growing up. I’m proud of that. It has served me well in sales.

A natural born salesman, that’s me. I’m not bragging, not at all. I know, in fact, that many people don’t even like salespeople. They think we’re unsophisticated and lowbrow, no matter what we sell. Me, I don’t care, not as long as I’m making the big money. And I have. It has been a great ride. Even Mia, when we first met, may have considered herself above me. She was a copywriter on the creative team and I was just a client services guy. Now she knows what’s what. It didn’t take long for me to teach her how the world works.

“Paul, I need to use the bathroom,” Mia announces, closing the magazine on her lap as if she could just pop out of the vehicle and relieve herself along the side of I-71.

“Oh, okay, I’ll pull off at the next exit and try to find someplace acceptable,” I say. The facilities on this road are subpar at best.

“Make sure it looks clean,” she adds as if I have X-ray vision capabilities. Typically, we do not take bathroom breaks on the drive to the lake house. The boys know this, Mia knows this. But in her weakened state, and on this, the best day ever, I will make an exception without shaming her. I’m in a loving, flexible mood.

“Right. Gas station or fast food? Your choice,” I offer. I’m not about to be blamed for choosing the wrong bathroom for her. This I say with warmth in my voice although I do not want to stop at all.

“I’ll let you know when we see the options,” she says, reopening the magazine. I’ll let it go, my disdain for the fact that she isn’t more appreciative of my willingness to stop for her. I glance at her, engrossed in the meaningless celebrity drivel opened on her lap.

She should stop reading that trash.

“You know that magazine is all gossip. The stories about celebrities are completely made up. Nobody is as happy or as sad as they make it seem in there. Life is lived in the middle. In middle America, like here, in the middle of nowhere, like now, and in the middle of life, like us,” I say. I’m feeling poetic today, although I don’t believe for a moment that I am normal, or in the middle of anything.

“Paul, I’ve never heard you call yourself middle-aged.” I think Mia is teasing me but there is an edge in her voice.

“I’m not,” I say. “All those guys are older than me in there. They get airbrushed. If you saw them on the street, you’d be disgusted at how old they are. It’s not real. That’s all.” I’m tired of this subject. I’ve never been a gossiper, or a reader of tabloid magazines, of course, but I know how the world works. People are always talking. Heck, a few years ago Mia heard from somebody back home that people think we aren’t happy. And just recently, the rumor has something to do with me flirting with a saleswoman at the mall. Ridiculous. I hate malls. As a rule, I shop at boutiques or online. Not that the gossips care to take a little thing like facts into account.

Anyway, back when the first wave of rumors started a few years ago, Mia launched what she called the “rebranding” effort on Facebook, posting photos of the two of us in various places, laughing and smiling together. Some of the shots are really old, but as long as I look good, I’m fine with it. She says it has worked, because she hasn’t heard the rumors anymore. I don’t tell her I have, and I certainly don’t mention the mall rumor, because she’d ask me when and where, who and in what context and I wouldn’t be able to tell her that, of course. I’m not a gossip.

I glance over and see my wife is reading an article about one of the late-night television hosts. Now, that’s a job I could nail. I mean, sitting behind a desk, talking with famous people about nothing but fluff and getting paid like a king. I don’t even know how you get a gig like that. As I look a bit closer, I realize the guy in the magazine looks a lot like Buck, our neighbor at the lake. Kind of a refined look, I guess you’d say. Lean but muscular build, dark brown eyes, a strong, manly jaw. It’s the type of look you see in New York, on Wall Street, or on television, not something you see around here. That’s what makes it odd that Buck lives at the lake year-round. Hardly anybody does because it’s cold and miserable in the off-season and nobody else is around. It’s like he’s a spy and he’s hiding from something or someone, that’s what I think.

He seems successful, though. I heard through the grapevine that he sold his big home somewhere in Connecticut when his wife died, and now he’s here “regrouping,” whatever that means. The woman who told me doesn’t know much, though she’s the designated neighborhood gossip for our block up at the lake. Every street has one. She’s just not very good at her job. Google knows a lot more about Buck than she does. And that’s not much.

“McDonald’s or BP?” I say as I pull to a stop at the stop sign. We’re in the middle of nowhere. The town of Kilbourne is several miles west down Route 521. A right turn will take us to a McDonald’s, a left is the gas station. And as far as I can see, there is nothing else.