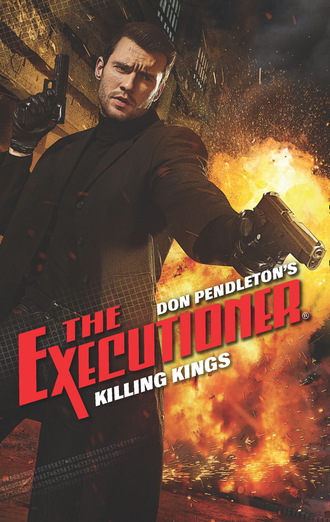

Полная версия

Killing Kings

The rub: by all accounts, Escobar was dead. And not just rumored to be dead, but shot to pieces by Colombian soldiers and DEA agents in December 1993, while fleeing from arrest in Los Olivos, one of Medellín’s middle-class barrios. According to the autopsy report, the drug lord had suffered wounds to his torso and legs, before a final gunshot drilled him through one ear.

There was no question of surviving what amounted to a point-blank execution. Photos of his corpse in situ, dripping blood and ringed by grinning slayers, had been broadcasted globally and still surfaced each year, around the anniversary of his passing. A painting by Colombian artist Fernando Botero showed Escobar writhing under a storm of bullets, gun in hand. At least eight books, which were penned by relatives, police and journalists, detailed the life and death of Colombia’s “King of Cocaine.” More recently there’d even been a TV series titled Narcos, running for three seasons that encompassed Escobar’s reign, his death and the succession of his Cali Cartel rivals to short-lived supremacy.

So he was dead, okay? And yet, if the DEA’s man on the street could be believed, together with his polygraph results, Escobar had not only returned, but also didn’t look as if he’d aged a day since drowning in his own blood on a Medellín rooftop.

Bolan and Brognola had talked about potential explanations. Escobar had two brothers but no twin, and if there had been a twin nobody noticed during eighteen years of international publicity, surveillance and even public interviews, said sibling would’ve aged since Escobar died, pushing age seventy by now.

Another thought: the lion’s share of Latin narcotrafficantes worshipped one or more orishas—deities of sects including Santeria, Palo Mayombe and plan, old-fashioned Voodoo, thought to safeguard criminals and bless their enterprises. Fine, but neither Bolan nor Brognola harbored a belief in zombies rising from their graves to walk abroad.

What then? Bolan had no idea as yet, but Brognola informed him that known enemies of the original, deceased Don Pablo had been dying off in waves of late, just when drug shipments from Latin America began to land on US streets. The latest were a top-ranked shooter for the Sinaloa Cartel and a former leader of the strongest group opposing Escobar during the early 1990s, Los Pepes, said to number officers of the Colombian National Police and Search Bloc among its members. The group allegedly dissolved when Escobar’s death made it superfluous, but Brognola had briefed him on a problem with that “common knowledge” spread by law enforcement and the media.

In fact, the Medellín Cartel was ravaged by arrests, convictions and assassinations in the months following Escobar’s death, and presumed extinct by spring of 1994. At the same time, however, the DEA had dropped the ball on tracking its successor, while they set their sights on Cali’s traffickers instead. Founded by Diego Murillo Bejarano, aka Don Berna, a one-time leader of the paramilitary United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, the revived cartel was dubbed The Office of Envigado, a town six miles southwest of Medellín.

Don Berna had been extradited to the States eleven years ago, pled guilty to smuggling tons of cocaine and laundering money, and received a sentence of 376 months in prison and a $4 million fine. He’d been transported to a federal penitentiary in Florence, Colorado, a supermax lockup nicknamed the Alcatraz of the Rockies.

But apparently the men and women he had trained to carry on without him—before he sought “peace” by surrendering more than 20,000 weapons and 112 properties worth $20 million to Colombian authorities—were still around and thriving in his absence.

Having visited Colombia on more than one occasion, Bolan readily accepted that. In fact, he’d have expected nothing less.

But now Don Berna’s brainchild had come under fire, along with rival Mexican drug syndicates, including those based in Sinaloa, Tijuana, Matamoros and Juárez. The homicides had not been singled out for special interest at first, as they had been lost in the fog of Mexico’s drug wars, which had resulted in 200,000 deaths and 30,000 disappearances over the past twelve years, with 1.6 million survivors driven from their homes by violence. Unknown gunmen had also launched strikes against cartels without fixed roots: the Knights Templar, La Familia, Los Zetas and the Beltrán-Leyva Cartel.

But once you focused on those hits, assuming that the DEA’s informer was correct as to the “ghost” he’d seen in downtown Medellín, the “random” slaughter made a grisly kind of sense. Pablo Escobar reborn, if such a thing were possible, would absolutely try to purge his former enemies, rivals who had co-opted his old drug routes, and the upstarts who had nerve enough to plant their flag so close to Medellín.

It made sense, right—except that no such thing was possible in Bolan’s universe.

One solid bit of information Hal Brognola had provided to him, as they’s strolled through Arlington, was the reported date, time and location of the next big cocaine shipment due from Mexico.

Bolan and his brother in arms, Stony Man flying ace Jack Grimaldi, were watching for it now, ready to strike.

* * *

There had been countless speeches and endless arguments over the wall planned for construction back in 2016, closing off unauthorized traffic between the States and Mexico. At first the government of Mexico was falsely advertised as paying for that barrier, a fabrication that the Mexicans dismissed as baseless fantasy. Next up, American taxpayers were supposed to foot the bill, and Congress finally had allocated $1.6 billion for construction, buried in a larger spending bill, but there’d been no physical progress yet—at least not on the stretch of border Bolan and Grimaldi had staked out.

And would a wall make any difference? Drugs had been flowing into the United States for decades now, by air, by water, stashed in vehicles that managed to evade dope-sniffing dogs at closely guarded border crossings. There had been narco submarines that Bolan knew of, and a whole maze of tunnels along the border, stretching west to east, from California to Texas. The Sinaloa Cartel had pioneered tunneling in 1989, between a private home in Agua Prieta, Sonora, and a warehouse located in Douglas, Arizona. Other syndicates had started burrowing since then, and for each tunnel located, the DEA presumed at least five more were moving dope around the clock.

“They’re here,” Grimaldi whispered, peering eastward across the sun-bleached open land through Steiner 210 MM1050 Military-Marine tactical binoculars.

Bolan shifted, following Grimaldi’s line of sight and saw two SUVs running tandem, raising plumes of dust behind them as they covered ground. He made them as a matched pair of Toyota RAV4s, either white or beige under their coats of desert grit, the better to pass unseen through the arid wilds of Southern Texas. Four men occupied each 4x4, and they were making for the point that Stony Man coordinates had marked as the drug tunnel’s adit in Val Verde County.

Bolan couldn’t see the tunnel’s southern terminus from where he lay, even with field glasses. The shaft might have been two or three miles long, for all he knew, bearing in mind that two things every drug cartel possessed were cheap labor and time. He didn’t know how long rotating crews might take to span that distance, digging night and day, nor did he care. The point was that transporters planned on moving through the tunnel here and now, clueless that they were being watched.

The pickup team wasn’t afraid of being seen by daylight—that much was apparent. Maybe they had worried more about missing their contacts in the dark, driving without headlights and only stars to guide them. On the other hand, perhaps they’d greased Border Patrol officers in advance to take a coffee break just now or simply look the other way. It had been true in Prohibition and throughout the modern War on Drugs.

Mexico particularly suffered from a scourge of bought-off law enforcement spanning decades, worsening as towns and villages descended into chaos. Its Federal Judicial Police force was dissolved in 2002, after one-fourth of its officers were linked to drug cartels, and its successor—the Federal Investigative Agency—likewise collapsed in 2005, with the arrests of its deputy director and 457 of its agents. After a four-year hiatus, the Federal Ministerial Police appeared, but nothing much had changed—at least if you believed the DEA and Texas Rangers.

The corruption wasn’t hard to understand: Mexican cops earned meager pay, and they were subject to the fear of having loved ones slaughtered by sicarios—hit men—the same as anybody else. Why swim upstream and be devoured by piranhas, when an officer could make a killing by just going with the flow?

The two RAV4s had stopped, disgorged their occupants—six of the eight packing assault weapons, and the drivers making do with pistols. Bolan heard them speaking rapid-fire Spanish, too fast and too far away to comprehend. Still, he had no trouble picking out the man who seemed to be in charge, the dark and bearded face filling his Steyr’s telescopic sight.

Waiting to see what happened next, he told Grimaldi, “On my call.”

“Call them,” Altair Infante ordered. “Now.”

His driver, Manuel Ortega, took a compact walkie-talkie from the cargo pocket of his khaki pants and pressed the talk button, saying, “Coyote calling Mole. Come in, Mole. Do you copy?”

Nothing right away, but then a voice came back at him through static. “Copy that, Coyote.”

“Where are you?”

“We’re at the hatch, just waiting for your signal.”

“This is it. Get out here, will you?”

“Yes, yes, give me a minute to lift this thing.”

“So, lift it!” Infante snapped, as if the team below ground could make out his words.

There was another brief delay, and then a hatch approximately ten feet square swung up and backward on hinges, with sand streaming from it as the adit of the tunnel was revealed. Blinking like real-life moles after their journey through the shaft, some of them coughing up stale air, four men emerged and stretched, feeling the sun before they turned around again and started dragging wooden pallets heaped with shrink-wrapped kilos of cocaine into daylight.

“Start counting them,” Infante ordered his soldiers. “And be quick about it. We need to get loaded up and gone before we have to deal with the Border Patrol, eh?”

“I thought you paid them off,” Ortega said, hoping it didn’t sound like he was whining.

“Who told you to think, idiot? Just do what you’re told and get a move on.” Turning toward the SUVs, Infante muttered, not quite underneath his breath, “Asshole.”

Ortega thought that he should say something, defend himself, but Infante was right: he wasn’t paid to think, only to follow orders without question, never mind what they might be or what he was required to do. Still, if only he had the nerve...

Half turning, driven by a wild impulse, Ortega had actually opened his mouth, could feel words forming in his mind and pressing on his vocal cords, ready to burst free from his tongue. It meant his death to speak, but how long could a man live once he was stripped of all his self-respect? That didn’t make him a man, someone to admire. It made him appear to be weak.

He was on the tipping point of suicidal madness when a bolt from heaven saved Ortega from himself, striking Infante’s head and blowing it apart, as if it were a mango with a firecracker inside.

Ortega had seen men killed before—had killed a few himself, in fact—but never had he seen a skull disintegrate, the brain within it taking flight and shredding while it tumbled through the air. One second he was staring at it, mouth agape, then suddenly a mist, red and gray and uncomfortably warm, spattered his face, smearing his Ray-Ban sunglasses. And—God Almighty—some of the muck was even in his mouth!

Ortega gagged and spat, while Infante’s gunmen and the hired transporters cried out in alarm. Then, a split second later, Ortega knew it couldn’t be a bolt from heaven that had slain Infante.

Would a bolt from heaven leave the flat crack of a military rifle floating on the desert breeze?

It was foolish even to suggest it.

But if they were under fire, that meant...

Ortega hit the dirt, shouting to his companions, “Incoming gunfire! Hit the ground!”

Instead of dropping to save themselves, the gunmen who’d accompanied Infante and Ortega in the SUVs were firing back at someone, something—maybe nothing, if the truth be told—with submachine guns and assault rifles. Ortega guessed they had to feel better, making so much noise, even if they couldn’t pick out a living target in the sandscape that surrounded them.

Thinking he ought to do something, Ortega reached for his own weapon, a Beretta M9 chambered in 9 mm Parabellum, with an ambitxterous safety and decocking mechanism making, it convenient for both right-and left-handed shooters. As a left-hander himself, Ortega babied the Beretta, cleaning it religiously and treating it as what he sometimes thought it was: his only true-blue friend on Earth.

But he still needed a target before he could use the weapon to good advantage.

So far he couldn’t tell if someone was still shooting at the pickup crew. Five other gunners, together with Ignacio Azuela, the driver of the second RAV4, were unloading into the desert to Ortega’s left, northwest of where he lay, the discharge of their weapons drowning out whatever hostile fire might be incoming now. Streams of bright cartridge casings glittered in the air and bounced across the desert floor as they landed.

Ortega squeezed off two shots in the general direction his companions were unloading, virtually blind until he realized that Infante’s blood and brains still smeared his Ray-Bans. He ripped them off, and had to squint against the glare of morning sun.

One target—that was all he needed to acquit himself with courage, but he still couldn’t find one.

Behind him, frightened cries and scuffling feet told him the underground transporters were retreating to their tunnel and, no doubt, would soon be fleeing back across the border to Mexico. Ortega wished that he could follow them, get lost somewhere in Coahuila and forget about the life he’d chosen, and never return.

But then he thought about his boss, who would never stop looking for a deserter from his family, and Ortega knew that sudden death, right here and now, was better than the screaming, inescapable alternative.

Chapter Two

After the first man had dropped, nearly headless, Bolan swiveled slightly to his right. It was enough for him to bring the tunnel’s entrance under fire from where he lay in the camo tarpaulin’s shade.

The men who’d begun to drag the pallets of packaged cocaine from darkness into daylight were unarmed, but they had been escorted from the other side by three cartel gunmen, no doubt assigned to keep the worker ants from snorting up along the way, and to avert hijacking on the Texas side, at least until the coke was packed into the white RAV4s and headed north.

That raised the number of gunmen to eleven, counting the two drivers with their sidearms, and now minus one: the seeming leader of the pickup crew Bolan had dropped with his first shot.

There’d been two reasons for his choice. First, the man giving the orders would be difficult to take alive, for questioning. Second, Bolan was satisfied that any member of the mobile team would know where they were meant to take the load. At that location he would certainly find more men, probably someone from the cartel’s midlevel management, who would impart more information, whether he liked it or not.

But Bolan was taking care of first things first.

He didn’t mean to let the workers, with their escorts, duck back into hiding and escape to Mexico unscathed, and absolutely not with the cocaine they’d brought across. From what he’d glimpsed of shrink-wrapped kilos, he projected that three standard wooden pallets should be heaped with fifty parcels each, or close to that. The standard pallet measured nine square feet and weighed approximately thirty pounds. Two men apiece could drag a pallet bearing fifty keys, the total weight around 140 pounds, maybe allowing stops for rest along the way.

The grunts wouldn’t have counted on a full load going home, and at the moment, under fire, delivering the cargo seemed to be the last thing on their minds. The six Bolan could see from where he lay were trying to escape, but one of the cartel gunmen had blocked the tunnel’s entrance with his body, shouting threats at them and leveling an MP5K submachine gun at his cringing, pleading team.

Enough of that, Bolan thought, as he zeroed his telescopic sight and stroked the Steyr’s trigger lightly to dispatch another single shot. Downrange, he saw the guard vault over backward, crimson spouting from a chest wound, dropping half inside the tunnel’s mouth.

That left the dead man’s workers in a quandary. Should they run past his corpse, desert the unexpected battleground and risk reprisal later, or pick up his gun and join the fight? If certain death waited on both sides of the bleak equation...

Bolan made the choice for them, spotting the worker closest to the fallen thug and drilling him between his shoulder blades. The dead or dying man dropped to his knees, then toppled forward, face dropping into the lifeless soldier’s crotch and lodging there.

Under the present circumstances, no one seemed to find that humorous.

“Ready?” Bolan asked Grimaldi.

“And waiting.”

“Go!”

They rose as one and swept the camo tarp aside, leaving one end secured behind them with two tent stakes, so it couldn’t blow away. That was the least of Bolan’s problems at the moment, but he usually tried to take away whatever he’d discarded at a killing ground, except spent cartridges from the unregistered Steyrs, which wouldn’t ring a bell at any law-enforcement database.

Grimaldi kept pace with him as they ducked and weaved, charging the twin RAV4s and the gunmen around them. The morning had been nearly silent till the SUVs arrived, but now it echoed with gunfire and stank of burnt gunpowder.

To the Executioner, it smelled like coming home.

Home was where the Devil waited for him. Home was where he hunted evil men.

* * *

Manuel Ortega had his targets now, but whether he could bring them down was anybody’s guess. They weren’t running away, but rather rushing toward him, which he guessed should make the killing of them easier. But they were also firing on his crew as they advanced, showing no fear, and not letting rapid forward motion spoil their aim.

Ortega fired twice at the taller of the two men, knowing that he’d missed each time before his spent shell hit the dirt. He’d jerked the M9’s trigger both times, as he’d practiced not to do on firing ranges, but the training vanished from his mind like the previous night’s dream when he had live targets in front of him. Even defeated, kneeling in desert graves they’d dug themselves and weeping like pathetic children, they unnerved him.

That made him pathetic in his own eyes, and Ortega resolved that if this was to be his dying day, he would not take it lying down, groveling in the sand.

Get up, then! he told himself. Stand up and kill them.

Ortega clambered to his feet, squeezed off another shot and missed both of his enemies again. He then started toward the nearer SUV. Ignacio Azuela crouched beside its left-front fender, shielded from incoming bullets by the RAV4’s bodywork and engine block, while two of the gunmen Infante had commanded stood beside him, firing Russian AK-102 assault rifles across the car’s roof, toward their adversaries.

From the sound of them, Ortega knew their would-be slayers’ weapons fired the same 5.56 mm rounds. A single shot could turn him into a leaking monstrosity like Altair, bleeding out into the desert soil.

“How many shooters?” Azuela asked, as Ortega dropped beside him, bruising both knees on impact.

“I’ve seen two,” Ortega replied. “Who knows if there are more?”

“This was supposed to be an easy job,” Azuela said.

Standing above them, now reloading, one of Infante’s gunners snarled, “Shut up! Stand and fight, before I drill your ass myself.”

Ortega knew he was addressing both of them, muttered, “Shit!” underneath his breath, then shrugged at Azuela and struggled to his feet again, using his free hand to support himself on the RAV4’s fender. It was hot from baking in the Texas sun, but that brief pain was nothing, next to the anticipation of his gruesome death.

This was the price Ortega knew he’d someday pay for choosing the life he had: smuggling drugs, beating and killing men he’d sometimes never met before, though others had been his friends before orders turned them into targets.

Hearing a sound rise from his throat that soon became a battle cry, Ortega lunged around the RAV4’s grille and rapid-fired the M9 toward his enemies until its slide locked open on an empty, smoking chamber.

He was fumbling with a second magazine, inside one of his cargo pockets, when they cut him down.

* * *

Jack Grimaldi watched the pistolero fall, his breastbone drilled and shattered by a tumbling 5.56 mm slug, and felt no triumph from the kill he’d made. In fact, the only thing he usually felt after slaying an enemy—whether on foot and face-to-face or in an airborne duel—was sweet relief.

A stranger had meant to kill him, but had died himself, instead.

Grimaldi knew that any fight you walked away from was a win.

The man he’d shot had died circling around the nose of one RAV4, but the gunners standing behind it plainly didn’t feel like making targets of themselves, when they could snipe at their attackers from behind their SUV.

No problem, he decided. Not unless the windows of their vehicle were bulletproof, that was.

From jogging forward, slightly off to Bolan’s left, Grimaldi stopped and took a knee, then leaned into the Steyr AUG’s stock, cushioned by a synthetic rubber shoulder plate. The rifle was selective fire, but had no switch to make the change; instead the weapon came equipped with a selective trigger—pulling it halfway meant semiautomatic fire, while squeezing it back all the way loosed a full-auto spray.

For this job, he bore down on the trigger and gave up counting rounds expended, sweeping back and forth across two dusty windows on the RAV4’s right-hand side. The safety glass—not bulletproof—shattered on impact, as did the glass in the windows along the driver’s side. Grimaldi’s 55-grain full-metal-jacket projectiles cleared both sets of panes, flying at some 3,200 feet per second, possibly diverted from their course a bit, but still finding the gunmen who had threatened him, piercing their centers of mass.

They fell together, dropping out of sight behind the SUV. One of them strafed the sky with a short burst as he was going down, and then Grimaldi dismissed them from his mind, knowing both men were dead or getting there.

Off to his right, Bolan was firing, dropping bodies. The Stony Man pilot glanced at his Steyr’s see-through magazine and counted roughly fifteen rounds remaining before he had to reload. A blur of movement from the second SUV in line drew him in that direction, while Bolan was taking down a couple of gunmen who’d kept their workers pinned at gunpoint, near the secret tunnel’s exit hatch.

As Grimaldi approached the second vehicle, a short gunman broke from cover, carrying what looked to be a Mini Uzi, trying to reload it on the run. The ace pilot didn’t know why he’d exposed himself before he primed his weapon, but it wasn’t his place to reject the shooter’s suicidal urge. Stroking the Steyr’s trigger twice, he punched holes, around lung-level, into the runner’s torso, and the fight went out of the guy for good.

How many active shooters left?

A hasty look around the battlefield showed him more hostiles down than up and moving. Two of those still on their feet were tunnel laborers, with their hands raised as high as they could reach, unless a sci-fi tractor beam hoisted them into the air. Their effort to surrender was in vain, though, as the last gunman who’d brought them through the tunnel stitched them both with automatic fire and laid them facedown in the sand.