Полная версия

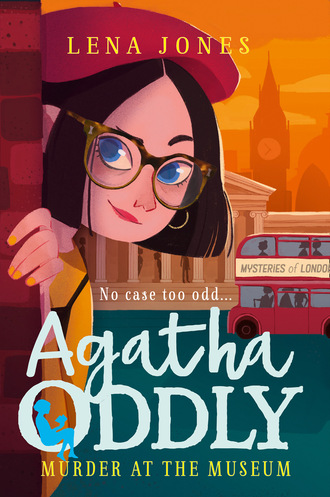

Murder at the Museum

It takes an almost Herculean effort to make it up the stairs. I have to stop partway up because my calves are aching badly. I bend over, panting and rubbing my legs, convinced my tracker will reach me. Then the area below lights up from their torch, and that’s enough of an incentive to send me climbing again, up and up, above the roof of the tunnel.

Finally, the spiral staircase ends. I see a small iron door in front of me; I put my Guild key into the lock; and, just as my pursuer’s foot sounds on the bottom rung of the metal staircase, I step through the door, out into the cold night air, and shut the door firmly behind me, panting loudly.

The moon is bright and full, showing me that the door is set into a stone embankment, near the Serpentine lake. I’m not far from home and I don’t have time to stand around. After taking a second to get my bearings, I race away across the lawns, into the night.

Usually, when getting home late, I climb back up the oak tree and in through the skylight. But there’s no way my legs will cope with that tonight. Plus, it’s so late that all the lights are off in the cottage. Dad must be in bed. I don’t want to spend any more time outside than I need to, not when somebody might still be tailing me. So I take out my house keys and, as quietly as possible, go in through the front door.

I collapse in the hallway, leaning against the front door and breathing heavily. The excitement of the evening, and the chase through the tunnels, have worn me out. But my mind’s as alert as ever, buzzing with ideas and theories, with images from the museum and the underground station.

I decide to get myself a glass of milk. Maybe that will help me get to sleep. There’s no point in me staying up all night, trying to solve a case where I don’t have all the facts. I will wake up rested tomorrow and start again, with Liam and Brianna to help me.

It’s dark in the kitchen, but I don’t want to turn the light on. The moon’s shining through the window and it’s just about enough to see by. I open the fridge, letting out a refreshing blast of cold air. I take out the milk, close the door, and turn towards the cupboard, where the glasses are kept.

As I do, I jump, so startled that I drop the carton of milk on the floor.

There’s someone standing in the corner of the kitchen, waiting silently in the shadows.

I stumble away, pressing my back to the work surface. Without taking my eyes off the intruder, I feel for a knife in the knife block. But my silent companion doesn’t move. I focus hard on their outline. There’s something not quite right about this person.

Walking over, I flick the light on.

For a few seconds, I’m blinded. But then I can see what startled me – one of Dad’s old suits. It’s hanging on a coat hanger from a hook on the wall, a double-breasted jacket over the trousers below. This is a particularly offensive article from Dad’s wardrobe: double-breasted brown twill with mustard pinstripes. Someone should have been arrested for creating this suit. And someone should definitely arrest Dad for wearing it. Knowing him, he’ll probably team it with a mustard shirt and his favourite green tie. I love him dearly, but his fashion sense could do with some help.

Dad said he had to visit another gardener in the morning, but why would he be putting on a suit to visit an orchid specialist? Especially a suit he hasn’t worn in years – a suit which, though it’s hard to believe, he thinks is very flattering. I walk up to the offending outfit and tentatively sniff it, and the smell it gives off confirms my suspicion – this suit has recently been dry-cleaned. It looks smart: pressed and lint-rolled of even the slightest speck of dust. Who is Dad trying to impress?

I pour myself a glass of milk, replace the carton in the fridge, turn out the light, and begin my weary climb to bed. I navigate my way upstairs, avoiding the creaky steps. I’m conscious that I’m still wearing my disguise and am now streaked with grime from the dirty tunnels through which I’ve been running and crawling. If Dad were to see me now, like this, his suspicions would certainly be raised.

Dad knows I love investigating, but I think he imagines that I’m out looking for people’s lost cats, or watching for shoplifters at the corner store. Not that there’s anything wrong with either of those, but I have bigger fish to fry. Dad doesn’t know about these bigger fish: about the Guild, or about the work they do, protecting the capital from the plots of dangerous, greedy people.

Which is for the best really.

I can hear Dad snoring loudly as I climb the stairs. At the top, a sudden ‘Meow!’ makes me freeze. Oliver has come to welcome me. He purrs loudly and pushes his stocky body against my legs.

‘Shhh, Oliver!’ I scoop him up with the arm that isn’t carrying the milk and let him drape himself round my neck. It’s far too warm for this, but I love feeling his vibrating purr. I wait for a moment, to make sure Dad’s still snoring, then creep up the flight of wooden steps to my attic bedroom.

I set Oliver down gently on the floor and look around me. Everything is laid out as I left it, but it seems like I’ve been gone for so much longer than a few hours – as though I left yesterday, or a week ago.

Adventure is a bit like that – you feel as though you’ve been moving very fast, and the rest of the world has been moving very slowly, and you can’t quite believe that it’s still Wednesday, or whatever day of the week it is, because it seems like you’ve lived a week – a month, a year! – in a short space of time. I suppose I like this feeling a bit too much – I rely on the adrenaline rush to keep my life from getting dull – but I try not to worry about that.

I go over to sit on my bed and sip at the glass of milk. I wonder if Mum ever felt like this, when she was a Gatekeeper. You don’t get into this line of work if you don’t like excitement – if you don’t thrive on risk. Did she worry that one day her escapades would get her into serious danger? Or did she live her life from day to day, not worrying about what tomorrow would bring? I look over at her photo on my bedside table.

Looking at this picture usually makes me feel sad or wistful, similar perhaps to what I’d feel if I was looking at a picture of a house that I used to live in – a happy memory. But, tonight, I don’t feel sad or wistful.

I feel angry.

I decide to analyse this new response. I run through what I know – and don’t know – surrounding her death:

1. Whatever happened to Mum, it wasn’t a bike accident.

2. I have a hunch that her death was linked to her work as a Gatekeeper.

3. Someone’s covered up what actually happened – could it have been the Guild?

I realise my new anger is because I’ve just had a close encounter with someone who almost certainly belonged to the organisation. I feel something close to rage at whoever caused Mum’s death – but also at whoever hid the truth from Dad and me. I close my eyes and focus on my breathing until I’ve calmed down enough to turn the rage into determination.

‘I will find out what happened to you, Mum,’ I promise her photo.

Finally, with no energy left to think or feel, I get under the covers, drink the last of my milk (thinking how Mum would have scolded me for not brushing my teeth) and turn the light out. Just before I drift off, I remember the swab that will need analysing. I grab my mobile, switch it on, and send Brianna a text, asking if I can go over to hers the next morning. Then I let sleep pull me under its thick surface.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.